This is a book review of Jill Lepore’s book “The Name of War: The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity” Vintage Books, a division of Random House, New York NY. 1999

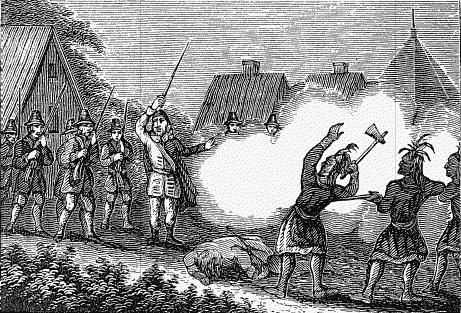

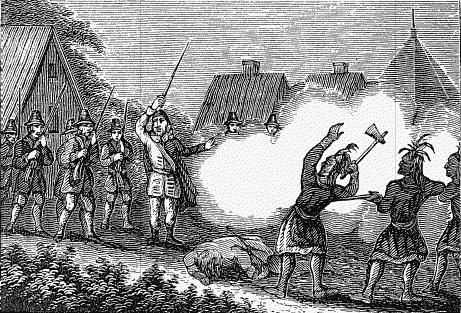

King Philip

King Philip

The thesis of Jill Lepore’s book “In the Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity” is that King Philip’s War helped lay the foundation of American identity. Lepore postulates that the history of the war and the war itself cannot be separated especially in regard to the identity of the participants. This is of particular interest in how the participants record the history of the war and how it influences their perception of themselves and their enemies.

War and how it is recorded in history can define a people. Examples of this can be seen throughout history. For instance the history and identity of Serbia cannot be separated from the battle of Kosovo in 1389 . There are countless other examples of how war shapes the identity of people and nations. One of the defining moments in the early history of Colonial America was King Philip’s War which lasted from July 1675 through August 1676.

Lepore maintains that King Philip’s War defined the ways in which the colonists and Indians shaped their views of themselves and each other, not just at the time of the war but in succeeding generations. She takes an approach unlike a lot of histories of war. Instead of simply analyzing battles Lepore looks at how war cultivates language and the questions that war provokes.

The most pressing to Lepore is “how do people reconcile themselves to war’s worst cruelties.”[i] She notes her own view of war in her introduction: “War is a contagion, the universal perversion. War is politics by other means, at best barbarism, a mean contemptible thing.”[ii] She says that her interest in war was drawn on the media coverage of the Persian Gulf War and her question of “how war could be represented without pictures.”[iii] This of course demonstrates how she views the nature of war and how she interprets it.

Lepore examines the literature of “King Philip’s War” beginning with the death of the leader of Wampanoag Indian King Philip in June 1675. She examines the war from both sides inasmuch as that only one side had access to the means to record that history. Through the writings of the colonists she examines the brutal nature of King Philip’s War which “in proportion to population… inflicted greater casualties than any other war in American history.”[iv]

This is not a campaign history. Instead Lepore selects incidents and battles of the war and looks at them through the eyes of the people that recorded them. Lepore notes that “the central claim of this book is that wounds and words-the injuries and their interpretation- cannot be separated, that acts of war generate acts of narration, and that both types of acts are often joined in a common purpose: defining the geographical, political, cultural, and sometimes racial and national boundaries between peoples.”[v]

Lepore’s account is a literary and philosophical study of the nature of war and not a military history. Her understanding of the totality of this war and its effect through the years is noted by others such as Russell Weigley.[vi] She asks a poignant question that should be noted by any practitioner of war or military theorist: “If war is, at least in part, a contest for meaning, can it ever be a fair fight when only one side has access to those perfect instruments of empire, pens, paper, and printing presses?”[vii]

Lepore studies the literature of the war published by the colonists. In particular she discusses the competing histories published by Increase Mather and William Hubbard, both pastors in New England and the writings of other colonists, especially those of Nathanial Saltonstall and Mary Rowlandson. For Lepore the importance of the writing of these people is connected to the identity of the peoples involved, both the English colonists and the Native Americans.[viii] Lepore’s premise is that the writings of the colonists “proved pivotal to their victory, a victory that drew new firmer boundaries between English and Indian people, between English and Indian land, and what it meant to be “English” and what it meant to be “Indian.””[ix] This is still a critical question. She notes how King Philip’s War influenced later events such as the American Revolution and the deportation of the Cherokee nation in the 1820s.

For Lepore the formation of the identity of both the colonists and the indigenous people is the key theme of this war, and for that matter most wars.

Lepore depicts this in her prologue and the account of the torture of a Narragansett Indian by Mohegans Indians while the English watch. The question that she raises and that she will ask again is “If they are to think of themselves as different from “these Heathen” whom they condemn for their “barbarous Cruelty,” how then can they consent to such treatment of a Narragansett before their very eyes? “Their enemy is killed, yet they do not have to kill him. They are allowed to witness torture, yet they not need inflict it.”[x]

Yet for the colonists such behavior risked their identity as Christians and Englishmen which was what they believed that they fought for in the first place. Lepore notes Mather’s 1674 sermon The Day of Trouble is Near which emphasized the theme of decay and confusion present at the time.[xi]

Lepore notes the effect of literacy on both the colonists and Indians. She begins with the murder of John Sassamon a bi-lingual Indian as the seminal event which set the stage for the war. She then examines Sassamon’s relationship to the English and Christianity and his relationship with King Philip. In Lepore’s account Sassamon was a victim of both his faith and literacy.

Lepore provides a good study of early missionary attempts to “bring the Gospel” to the Indians by translating the Bible and devotional texts from English to Massachusett[xii] and how that missionary activity converted many Indians including Sassamon. Lepore notes that: “in a sense literacy killed John Sassamon. And herein lies one of the fundamental paradoxes of the waging and writing of King Philip’s War: The cultural tensions that caused the war – the Indians becoming Anglicized and English becoming Indianized- meant that literate Indians like John Sassamon who were those most likely to record their version of events of the war, were among its first casualties.” [xiii]

Lepore’s depiction of the cruelties of war in chapters three and four is a study in contrasts. Again this comes back to a question of identity for the colonists. They saw themselves as different from the “uncivilized Indians” even the Christian Indians. This was because the colonists believed that Indians did not value English understanding of identity which was connected to property and its improvement, houses, land and farm field’s cattle and possessions. When the Indians destroyed English property it was a blow at their very identity as Englishmen. The tension between these tow opposite points of view remains a fixture of American life.

Religion played a major role in the conflict. Lepore notes that “the colonists’ sense of predestination…, their natural affinity with the land, and their cultural proclivity to conflate property with identity, all combined to produce this oneness of bodies and land.”[xiv] The English did not view the Indians as having the same values because they did not have the same understanding of land and property, and thus they saw them as savage. For example she discusses how the colonists view of how “the Algonquians’’ perceived nomadism, their failure to “improve” the land, formed the basis for the English land claims….”[xv] In other words the English Colonists believed that if the Indians were want to improve the land upon which they dwelt than they did not deserve to remain on it.

Lepore discusses the metaphor of “nakedness” in relation to the loss of property and identity.[xvi] She notes how the Indians seemed to have understood the importance of land and property to the English. She cites a note left by a Nipmuck Indian at Medfield “we hauve nothing but our lives to loose but thou hast many fair houses cattell & much good things.”[xvii] She notes that the note offered an analysis missed by all the English accounts of the war.[xviii]

Likewise Lepore notes how religion informed both the colonists and Indians who both looked for supernatural messages in the natural world. The English colonists, primarily Puritan Calvinists believed that the devastation of the war on them at the beginning of the war was “God punishing them for their sins, not the least of them their failure to convert the Indians to Christianity.”[xix] The English settlers were influenced by their Calvinist theology and believed that the Indians both “served the devil” but were also “the instruments of God.”[xx] The Indians also had a spiritual element to their conduct of the war and the clash of these beliefs gave the war a religious dimension especially for the Colonists a dimension that would pervade American perceptions of many of the wars which followed.

Another theme of Lepore in how the war shaped identity is in the context of the bondage experienced by the English captives of the Indians during the war that of and of the Indians following the war. She uses the stories of Mary Rowlandson and Christian Indian James Printer to illustrate her thesis.

Rowlandson’s story is the account of her capture, captivity and release by the Indians following the attack on Lancaster, Massachusetts in February 1676. Lepore calls the importance of Rowlandson’s account The Sovereignty and Goodness of God and how it shaped the colonial and later American understanding of the war by “the nearly complete veil it has unwittingly placed over the experiences of bondage endured by Algonquian Indians during King Philip’s War.”[xxi] Lepore writes that for Rowlandson and Printer that the story was one of redemption and return to English society, Rowlandson through her book, Printer through bringing back scalps of other Indians as a demonstration of his loyalty to the Colonists.[xxii]

Another point raised by Lepore here is the enslavement and deportation of the Algonquians by the Colonists following the war. A key to the thinking of the colonists is elaborated by Lepore: “In the end, the colonists’ evaluation of Indian sovereignty was merely an extension of their thinking about Indian possession: Indians were only sovereign enough to give their sovereignty away.”[xxiii]

This again comes back to Lepore’s thesis of identity. She states that the “colonists moved toward (but never fully embraced) in their writing about King Philip’s War was the idea that Indians were not, in fact truly human, or else humans of such a vastly different race as to be considered essentially, and biologically inferior to Europeans.”[xxiv] She argues that King Philip’s war was a defining moment where “Algonquian political and cultural autonomy was lost and where the English moved one step closer to the worldview that would create, a century and a half later, the Indian removal policy of Andrew Jackson.”[xxv]

Lepore’s final section deals with memory and identity. She illustrates this by noting how the Reverend Nathan Fiske in 1775 equated the British to the Indians of King Philip’s War; and the play Metamora written in 1829 about King Philip and the war. Both Fiske and the latter play had an impact.

Fiske’s sermon helped light the fires of American independence movement, something that which Lepore notes for the Indians was “not a gain but a loss of liberty.”[xxvi] The play Metamora opened the day Andrew Jackson declared his policy of Indian removal. It was the most popular American play of its era. Lepore says that when you “peel back all the layers …what remains is a struggle for American and Indian identity. Through plays like Metamora, white Americans came to define themselves in relation to an imagined Indian past.”[xxvii]

Overall Lepore’s treatment of King Philip’s War is a good treatment of how wars affect people and their relationships with those whom they war against. Using Lepore’s thesis of the war, the history of war and how they shape the identities of peoples and nations’ one could conceivably analyze other conflicts from this perspective.

Since this is the premise of why Lepore began her study of King Philip’s War it is worthy of further discussion. Such studies could be undertaken in the Balkans, Kurdistan, Palestine, Iraq or Syria as well as other regions where the impact of war is thoroughly ingrained in the minds, hearts and imaginations of the parties involved. From this perspective one wonders what future generations of Americans and Moslems will write of the current conflicts that the United States is engaged in.

Another aspect of Lepore’s examination study is religion in the perception and interpretation of war. In this case it is the impact of the colonists Calvinism and its relationship to other English theologies of its day as well as other Calvinistic understanding of war of that era that matters.

This is very important. The more recent English colonists prior to King Philip’s War had in many cases experienced the brutality of English Civil War and the protectorate of Oliver Cromwell in which they dominated the English political landscape. Thus for many of these colonists a return of the Crown and Anglicanism would drive them to seeking independence for the colonies.

Many of the soldiers among them would certainly recall the brutality of the civil war and the invasion of Ireland. The soldier’s views of the Irish were similar to the views of the colonists of the Indians, something that Lepore only mentions in passing. As such the experience of the more recent colonists and the soldiers added a dimension of brutality that was not as prevalent before the hostilities.

Likewise Lepore mentions little of Roger Williams’ beliefs and his relations to the Puritans whom he fled to found Rhode Island in 1631 on the principle of religious freedom. Her treatment of Williams does not include his respect for the Indians and view that “perhaps their religion was acceptable in the eyes of God as was Christianity.”[xxviii] Despite this her treatment of King Philip’s War is worthwhile reading because it brings up the question of identity which seems to drive war and those who write of it to the present day.

The question that Lepore forces us to ask is how past wars shape our conduct in and interpretation of ongoing wars. The Colonists would see their conflict with the Indians as one of life and death, one of their very survival as a people and as such they were willing at times to commit atrocities against Indian threats, real and imagined. More recently the American understanding of the war against Japan was conducted in a similar vein with many of the same overtones. Likewise the framing of the current war by some as a war of survival against the threat of Islam raises similar issues. Thus Lepore’s study is valuable in examining how some view the current war on terror as well as a means to look at other wars in our nation’s history through a different lens, not simply through the eyes of battles, military forces, strategy and tactics but through the participants identity and who the war is both shaped and recorded by both sides. Even if one does not accept her conclusions or her admitted biases the book can allow us to reexamine our own views of our past and how they shape our present view of war, conflict and identity as a people.

[i] Lepore, Jill. The Name of War: The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. Vintage Books, a division of Random House, New York NY. 1999 p.xxi

[ii] Ibid. p.x

[iii] Ibid. p.xxi

[iv] Ibid. p.xi. Additionally, Allen R. Millet and Peter Maslowski in For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America The Free Press, NYew York, NY 1984 note that “the colonists did not enjoy an “Age of Limited Warfare” like that which prevailed in Europe from the mid-seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century. To the colonists (and to the Indians) war was a matter of survival. Consequently, at the very time European nations strove to restrain war’s destructiveness, the colonists waged it with ruthless ferocity, purposefully striking at noncombatants and enemy property.” p.18

[v] Ibid. p.x

[vi] Weigley writes in “The American Way of War: A Study of United States Military Strategy and Policy, Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN, 1973 that “In King Philip’s War of 1675-76, the Indians came fearfully close to obliterating the New England settlements. When the colonists rallied to save themselves, they saw to it that their victory was complete enough to extinguish the Indians as a military force throughout the southern and eastern parts of New England…” and that he “logic of a contest for survival was always implicit in the Indian wars, as it never was in the eighteenth-century wars …”p.19 Weigley notes how this would impact future American Wars beginning with the War against France and later the American Revolution in that “their success demanded the complete elimination of British power from all of North America, just as they had demanded and won the complete elimination of French power.” p.20

[vii] Ibid. p.xxi

[viii] Ibid. Lepore. p.x

[ix] Ibid. p.xiii

[x] Ibid. Lepore. p.4-5

[xi] Ibid. p.6. Lepore notes a theme that will be later picked up by many in American history. The idea that they were visible saints for all of Europe to see is a precursor to the idea of the United States as “A city set on a hill.”

[xii] See Leopre pp.33-39

[xiii] Ibid. p.25-26

[xiv] Ibid. p.82

[xv] Ibid. p.76

[xvi] Ibid. p.79

[xvii] Ibid. p.94

[xviii] Ibid. pp.95-96. Lepore notes that the English interpreted Algonquian assaults and taunts as “expressions of mindless savagery rather than calculated assaults on the English way of life.” And the refusal of the English to “place Indian “cruelties” within the broader context of Algonquian culture, instead labeling them “barbarous” violations of English ideas of just conduct in war….”

[xix] Ibid. p.99

[xx] Ibid. p.102 Lepore does not dwell on this but this observation is entirely consistent with Calvinist theology which drew heavily on the Old Testament imagery of Israel and its relations with its neighbors. The Old Testament prophets often spoke in terms of the enemies of Israel being used by God to punish Israel for its sin and disobedience to God.

[xxi] Ibid. p.126

[xxii] Ibid. p.147-148

[xxiii] Ibid. p.165

[xxiv] Ibid. p.167

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ibid. p.189 ff. Lepore chronicles the losses of Freedom in the various states to the different tribes of New England.

[xxvii] Ibid.p.193

[xxviii] Gonzalez, Justo. The History of Christianity, Volume 2: The Reformation to the Present Day Harper and Row Publishers, San Francisco CA. 1985 p.225