Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

There are some things that should not be forgotten, unfortunately many of them are lost to history. One of these events was the American assault against the Japanese fortress on Tarawa Atoll in November 1943. The battle was one of the deadliest encounters of the Second World War, and was waged for the control of a tiny coral atoll that only occupied one square mile of the earth’s s surface. Dug in on that atoll were about 4,000 Japanese defenders.

The only Japanese officer to survive, Warrant Officer Kiyoshi Ota recalled, “We could see the American landing craft coming towards us like dozens of spiders over the surface of the water. One of my men exclaimed, ‘The God of Death has come!’”

I hope that this small attempt to detail that battle helps you understand the sacrifice of the men who fought there.

Peace

Padre Steve+

The American Decision: Operation Galvanic

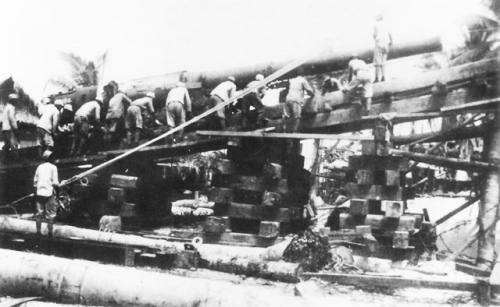

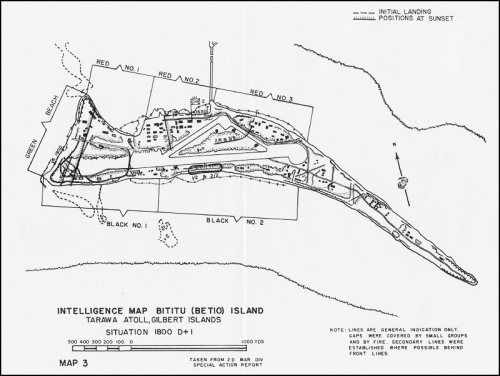

The Target: Betio Island, Tarawa Atoll

Following the Guadalcanal campaign and the shift of significant naval forces away from the Solomons, the focus of the U. S. Navy and Marine Corps shifted to operations in the Central Pacific. Unlike the Solomons campaign, which was initially a Navy and Marine Corps Operation, but shifted to Army control under General Douglas MacArthur as the campaign shifted to Borneo; the operations in the Central Pacific would be an almost total Navy and Marine Corps operation.

Operation Galvanic was the first offensive operation in the Central Pacific. It came about as a result of the Joint U.S. Strategic Committee decision in April 1943 to favor an advance in the Central Pacific while continuing to maintain McArthur’s offensive in the South Pacific.[i]

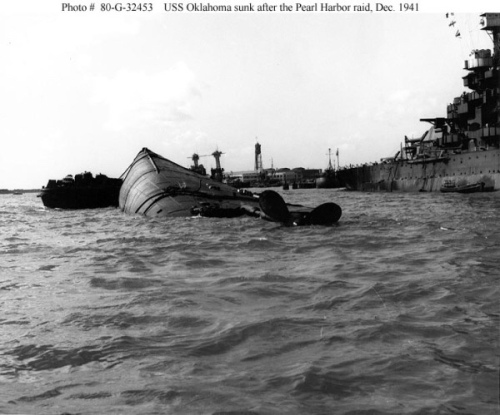

Betio Island after the Battle

The driving force behind this strategy was Admiral Ernest King. King fought for the plan and “insisted that any campaign should focus on the destruction of Japan’s overseas resources, which meant an offensive directed only toward the Western Pacific sea lanes.”[ii] The Joint Chiefs believed that a simultaneous attack by the forces of Admiral Chester Nimitz in the Central Pacific, and MacArthur in the South Pacific would “keep the Japanese guessing” in regard to which direction the Americans would strike. [iii] The decision of The Joint Chiefs was presented to the British at the TRIDENT meetings in May 1943 and while the British resisted the American plans, a compromise was reached which allowed the Americans to “simultaneously…maintain and extend unremitting pressure against Japan….”[iv]

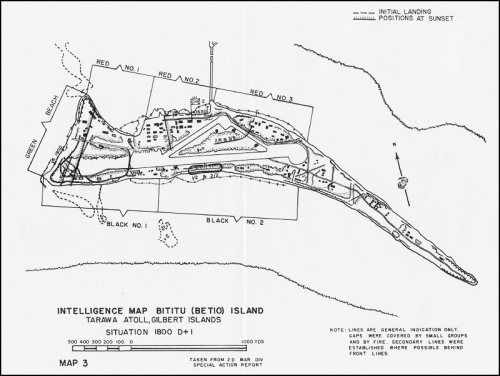

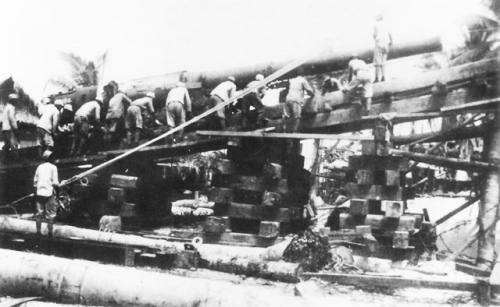

Japanese Troops Emplacing 8″ Vickers Gun

The decision to begin operations in the Central Pacific meant that the priority that MacArthur’s had been given in logistics and personnel would be reduced in order to launch the Central Pacific operation. MacArthur protested to no avail, and the Joint Chief’s stood firm in their decision that the Central Pacific operation “would make it easier to isolate Japan from her domain in the south.”[v]

MacArthur was allowed to continue OPERATION CARTWHEEL in order to neutralize the key Japanese base at Rabaul while Nimitz’s forces attacked the Marshall and Caroline islands.[vi] Nimitz’s staff began their preparations and decided on a conservative course to capture the Gilberts first before taking the more heavily defended Marshalls.[vii] This was in part due to the “need to minimize the risks to his untried amphibious forces against such heavily fortified enemy bases out of reach of air cover.”[viii]

Japanese Naval Infantry conducting Live Fire with Type 99 Machine Guns

Several factors were considered by Nimitz and his planners considerations in this choice. Nimitz did not have enough troops to capture all of the vital heavily defended locations in the Marshalls without dividing his forces.[ix] Additionally the Gilbert operation could be supported by land based bombers.[x] A final consideration was the Joint Chief’s decision to allow MacArthur to retain control of 1st Marine Division, which Nimitz had hoped to employ in his operations in the Central Pacific.[xi] The Staff of CINCPAC did a thorough photo reconnaissance of the Gilbert’s, and convinced the Joint Chiefs that Tarawa and Makin needed to be taken to provide air bases for the assault on the Marshalls. Finally, the order for Galvanic was issued on 20 July 1943 with its execution planned for November 1943.[xii]

Japanese Preparations

Rear Admiral Keiji Shibasaki

“It will take a million men a thousand years to take Betio”

The Japanese had done little to prepare against potential American offensive operations against the Gilbert’s until Makin Island was raided by elements of the 2nd Raider Battalion in August 1942. The Makin raid shook the Japanese and they reinforced Makin and occupied Betio.[xiii]

The Japanese deployed the Yokosuka 6th Special Landing Force, essentially Naval Infantry or Marines[xiv] and the 111th Construction Battalion to Betio on 15 September 1942, over nine months after they attacked Pearl Harbor.[xv]

These forces were commanded by Admiral Tomanari Sachiro, who at once began to fortify Betio. Tomanari was a skilled officer who appreciated the value of strong fortifications on exposed islands like Betio. Likewise, recognizing that his forces were inadequate to the mission, Tomanari asked Tokyo for reinforcements. The reinforcements came in the form of Commander Sugai’s 7th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force, which landed on 14 March.[xvi]Commander Sugai’s troops were the famed Rikusentai, the best of the Japanese Navy’s land forces and considered to be better disciplined, trained, and effective than Imperial Army Units of the same size.

Japanese Gunnery Exercises before the Invasion

The fortification of Betio proceeded slowly until Rear Admiral Shibasaki relieved Tomanari, who returned to Japan. [xvii] Shibasaki was a tough veteran of service at sea and ashore including 19 months as a Rikusentai[xviii] officer in China. Shibasaki was chosen by Admiral Mineichi Koga, Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto’s to instill a better fighting spirit on the island.

The Imperial General Headquarters, issued a “New Operations Plan,” which ordered the outer defensive islands, such as Tarawa, to “hold up any American advance while an inner line of fortresses was constructed….”[xix]

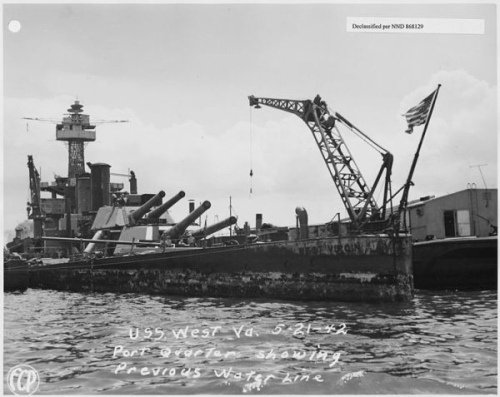

Shibasaki drove the garrison hard, inspiring them to “extraordinary heights of labor that resulted in Betio’s superb defenses.”[xx]Betio mounted four 8” Naval guns[xxi], four 14 cm guns, four dual mount 5.5” dual purpose guns[xxii] six 80 mm anti-boat guns, eight 75 mm dual purpose guns, ten 75 mm mountain guns, six 70 mm guns and nine 37 mm anti-tank guns, numerous machine guns. The defenders were also equipped with light AA guns and 14 Type 95 Ha-Gō light tanks.[xxiii]

These weapons were mounted in well camouflaged, armored, or reinforced pillboxes, connected by trenches. [xxiv] In accordance with the directives of the high command, Shibasaki ordered his troops “to defend to the last man all vital areas and destroy the enemy at the waters’ edge.”[xxv]

The Japanese records note that Shibasaki “immediately began to strengthen morale and carried out advanced training, and as a result…the garrison remarkably enhanced its fighting capability and they were full of confidence.”[xxvi] Even the service troops were thoroughly trained to fight from their superb defensive positions.[xxvii] Shibasaki reportedly told his men that it would take a million men a thousand years to take Betio.

American Preparations for Galvanic

LVT Amphibious Tractor

Nimitz organized his forces into three major commands, the 5th Fleet, commanded by Admiral Raymond Spruance, the 5th Amphibious Force under Admiral Richmond “Kelly” Turner, and the V Amphibious Corps under Major General Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, USMC.[xxviii] The 2nd Marine Division, which was assigned to assault Tarawa, was commanded by Major General Julian Smith.

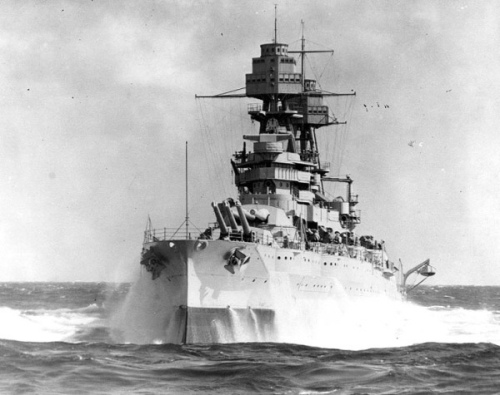

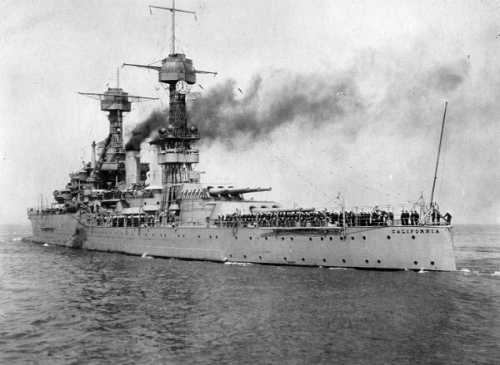

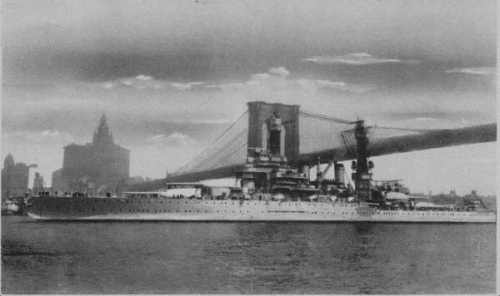

The force that sustained this operation, and the subsequent amphibious operations was the Service Force Pacific Fleet.[xxix] This was a collection of ships whose mission it was to sustain the fleet in mobile operations. [xxx] This force, greatly “increased the range and power of the Navy in amphibious operations.”[xxxi] The plans for Galvanic called for the Army’s 27th Division take Makin Island, and the 2nd Marine Division which had been blooded at Guadalcanal, to take Tarawa, supported by the carriers and battleships of Admiral Raymond Spruance’s 5th Fleet.

Galvanic was the first application of new amphibious tactics developed for the Pacific war.[xxxii] Air and sea bombardment would precede the actual assault. The Marines would be transported ashore in a new vehicle called an LVT (Landing Vehicle Tracked) and other amphibious ships and craft including the LSD (Landing Ship Dock), LCM (Landing Craft Mechanized) and LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel).

The LVTs were absolutely vital at Tarawa because of the distance that the reef extended from the beaches. The LVT’s, nicknamed “Amtracks” or “Amphtracks” were essentially a tracked amphibious personnel carrier. They were developed from a commercial vehicle used by U.S. Forrest Service Rangers in the Florida Everglades and were capable of crossing coral reefs that other craft could not cross.

The early LVTs had retrofitted armor and mounted a .50 cal. machine gun. At Tarawa the Marines deployed 75 LVT-1s[xxxiii] and 50 LVT-2s. A total of 93 LVTs were part of the first wave of the Marine assault.[xxxiv] The LVTs were transported to Tarawa aboard LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks.)

Other innovations in this new form of amphibious warfare included the assignment of Naval Gunfire Support teams to the Marine Regiments, and down to some battalions. [xxxv] The attack at Tarawa was the first time that the Marines used the M4 Sherman tank in combat. [xxxvi]

Tarawa, ended up being a real combat proving ground for the tactics and equipment which would be improved on and used in every subsequent amphibious operation in the Pacific. Tarawa also marked the last major use of rubber landing craft by the Marine Corps in an opposed landing.[xxxvii]

There were limitations to American preparations. First the size of the force meant that it could not be assembled in one place for rehearsals or to train as a team.[xxxviii] A second problem for the Americans was the assumption that high and low tides would be sufficient to get their landing craft across the reef in spite of warnings to the contrary.[xxxix] Likewise, the Americans failed to completely anticipate the scope to which the Japanese had fortified the island.

The latter was a failure of commanders to appreciate good intelligence that had been provided to them. In particular, aerial photos taken by the Air Force, and ULTRA intercepts provided good information on the strength and composition of the Japanese units on the island, as well as the layout of the defenses.[xl]

Likewise, some important equipment shortages were not remedied. The Marine Bazooka’s did not arrive, and neither the 6th or 8th Marines had ever made an actual amphibious assault. At Guadalcanal the these regiments made an administrative landing, and few field-grade officers remained from the 2nd Marine Regiment who had landed at Tulagi.[xli] Despite their combat experience, they were far from the “amphibious experts” that they would become.[xlii]

However, they made up for their lack of practical amphibious experience by their cohesiveness, high morale and esprit. Likewise, they were well armed and equipped, in top physical condition and knew the basic tools of their trade: “weapons proficiency and field firing, close combat techniques, fire and maneuver, tactical leadership, fire discipline.”[xliii]

Japanese Vickers 8″ Gun Emplacement

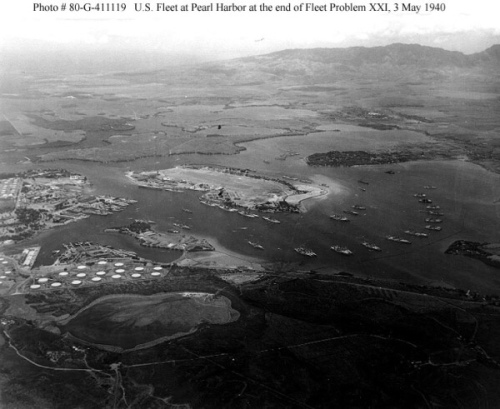

The most critical aspect of the operation was to get across the reef onto the island. There were few good landing sites and it was decided to make the landings from inside the atoll’s lagoon onto the Betio’s north shore. This decision meant that transports embarking the Marines would have to unload outside of the lagoon and that the landing craft would have to make a 10 mile trip to get to the beaches.[xliv]

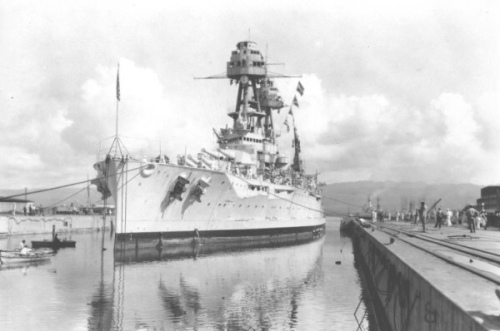

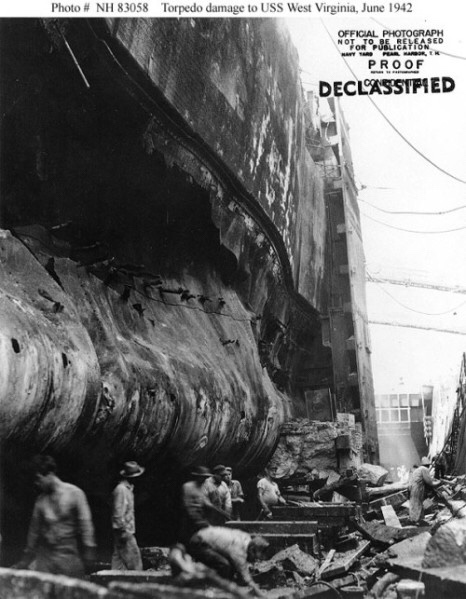

Another problem was that there was only one entrance into the lagoon, and it was not deep enough for heavy ships to enter.[xlv] This meant that ships such as battleships and cruisers would not be able provide direct, close range fire on the Japanese positions which were best situated to disrupt the Marines.

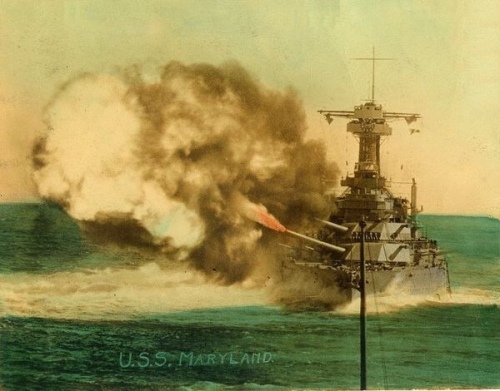

The execution of the plan involved land based bomber strikes beginning on D minus 7. Carrier aircraft would begin their operations on D minus 2. Cruisers and destroyers joined the cacophony of destruction on D minus 1 and the battleships on D-Day itself.[xlvi]

On D-Day the Navy planned to bombard the island with 3,000 tons of shells in 2 ½ hours.[xlvii] The Navy was confident in its bombardment plans. Rear Admiral H. F. Kingman, who commanded the fire support group declared “We will not neutralize; we will not destroy; we will obliterate the defenses on Betio!”[xlviii]

Four battalions of Marines would land in the first wave, the three battalions of the 2nd Marines Regiment, and 2nd Battalion 8th Marines, all commanded by Colonel David Shoup.

Colonel Shoup would win the Medal of Honor on Betio and later became the Commandant of the Marine Corps. However, he assumed command of the 2nd Marines when the Regimental commander fell ill on the journey to Efate.[xlix] The division reserve were the remaining two battalions of the 8th Marine Regiment. The Division’s 6th Marine Regiment served as the corps reserve.[l]The assault units would be reinforced by tanks, and the 1st and 2nd Battalions 18th Marine Regiment, the division’s combat engineers.

The Invasion: Day One

Marines Going Ashore on Day One

The final naval gunfire bombardment commenced at 0542 hours on 20 November, and the assault waves began their trek to the beaches. The transports were out of range of Japanese guns, but since they were so far out, the small amphibious craft boats have to make a 10 mile trip to get to the beaches. [li]At this point things began to go seriously wrong for the Marines.

LCT (Landing Craft Tank) Sinking after Being Hit

Unfortunately, Admiral Kingman and the Navy had “badly miscalculated the amount of softening-up that could be done in two and a half daylight hours bombardment.” Although the bi Vickers guns were silenced, not enough damage was done to the Japanese defenses.[lii] The Japanese unwittingly helped the Marines by firing their larger guns at the warships instead of holding fire, thus identifying their positions to Navy gunners.[liii]

The bombardment was lifted to allow an attack by carrier based aircraft. However, the aircraft were late to arrive and the ships did not resume fire, allowing the Japanese to emerge and re-train their weapons on the approaching landing craft.[liv] Likewise the destroyers USS Ringgold and USS Dashiell, the only ships operating inside the lagoon and providing close Naval Gunfire Support, were ordered to cease fire, knowing the Japanese gunners along the shore were still active.[lv] Some believe that an extra half hour of direct fire from the destroyers would have saved many lives.[lvi]

The LVTs in the first three waves were delayed by a heavy chop outside the lagoon and did not make landfall until 0913, which threw off the landing schedule.[lvii] The expected and planned for rise in tides did not materialize, and tides remained unpredictably low for the first 48 hours. As a result, no landing craft other than the LVTs could cross the reef, and the Marines were forced to wade ashore from distances of 600 to 1000 yards.[lviii]

Marines Wading Across the Lagoon

Shoup’s Marines landed on three beaches. Red One and Red Two lay to the west of a 500 yard long pier, while Red Three lay to the east. Third Battalion Second Marines (3/2) landed on Red-1, while 2/2 on Red-2. Second Battalion Eighth Marines (2/8) landed on Red-3, while elements of 1/18 and the scout snipers landed at the pier, with First Battalion Second Marines (1/2) remained at sea in reserve to land behind the battalion making the best progress.[lix]

As soon as the Amtracks hit the reef the Japanese began firing. Every “working weapon along the north and west shorelines….blazed forth in fierce, interlocking fields of fire.”[lx] As they watched the Amtracks craw over the reef that Japanese knew they were in for a tough fight, one of Warrant Officer Ota’s men exclaimed “Heavens! The God of Death has come!”[lxi]

The Marines of 3/2 on Red-1 received enfilade fire from Japanese guns emplaced in a U around the beach. Even before the Marines landed they began to take causalities, Amtracks were hit in the lagoon and most that were not sunk or destroyed were unfit for further use.[lxii] The 2000 Marines who landed on the beaches in the first hour of the assault were badly disorganized, and the commanding officer’s of 2/2 and the Amtracks were killed. 3/2’s commander was isolated on the reef and only 2/8’s commander was with his troops. 2/8 was the only battalion being to reach the shore relatively intact.[lxiii] 3/2 was down to 65% of its strength and Kilo Company, 3/2 had taken over 50% casualties.[lxiv]

The Marines in the fourth to sixth waves were struggling to wade ashore from the reef. Landing craft “ran aground or milled about helplessly outside the reef, which was swept by crossfire from behind the beaches and from a grounded hulk northwest of the pier.”[lxv] Most of the tanks were put out of action either through accurate fire by Japanese guns or by sinking in deep areas of the lagoon, the Tank battalion commander was blown out of his Amtrack, wounded and survived 24 hours by clinging to a pile of dead bodies to keep from drowning.[lxvi]

Colonel Shoup Directing Operations

Colonel Shoup landed at Red-2 and began directing operations on the beach. He knew that he had to get more troops ashore to exploit the minimal gains his Marines had made. The news from Red One and Two was bad; he decided to bring 1/2 in at Red-2 thought that 3/8 should go in at Red-3.[lxvii] At 1018 General Julian Smith ordered the 8th Marines to dispatch 3/8 to Red-3.[lxviii] The Marines of 3/8 had to make their way across 700 yards through the water to get to the beach. They were slaughtered, and only 30 percent of the first wave got ashore, while the second and the third “were practically wiped out.”[lxix]

Close Combat

As Shoup’s Marines struggled to reach the beaches, those who had gotten ashore engaged the Japanese at point blank range. First Lieutenant William Hawkins of the 2nd Marine Scout and Sniper platoon and five of his men engaged the Japanese on the pier in vicious hand to hand fighting. [lxx] Staff Sergeant Bordelon of the Engineers on Red-2 though grievously wounded knocked out four gun positions, some by lobbing dynamite charges into them and galvanizing survivors into action, finally being killed while taking on a Japanese position alone. Both Marines would be awarded the Medal of Honor.[lxxi]

Wounded Being Evacuated by Rubber Raft

By afternoon Julian Smith realized that he needed more troops, his last battalion, 1/8 waited to go ashore.[lxxii] Smith asked for the 6th Marines. He had Rear Admiral Wilbur Hill, Commander of Amphibious Group Two, send a message to Admiral Richmond K. Turner stating “Issue in doubt. I concur.” This message sent a chill through the listening Naval Staff.[lxxiii]

Ashore, Colonel Shoup brought in howitzers from 1st Battalion 10th Marines on his surviving Amtracks to the eastern edge of Red Two near the pier. [lxxiv] The howitzers landed in the early evening.[lxxv] Shoup sent Lieutenant Colonel Carlson to make a personal report to General Smith that he would hold onto his beachhead no matter what happened.

Shoup ordered his Catholic Chaplain to lay out a cemetery and begin burying the dead who were already decomposing in the tropical heat.[lxxvi] As this transpired, 2/8 got two of its 37mm anti-tank guns into position to drive off Japanese tanks approaching the beachhead.[lxxvii]

Members of the Second Marine Division Band assisted Navy Hospital Corpsman in bringing back wounded Marines.[lxxviii] For the rest of the day the Marines continued to eke out a beachhead. Shoup’s Marines on Red-2 and Red-3 managed to advance about halfway across the island, while 3/2 and elements 1/2 and 2/2 were isolated. Major Ryan of Lima Company 3/2 pulled them back to meet an expected Japanese counter-attack.[lxxix]

By nightfall the Marines had taken over 1500 casualties of 5000 men landed the first day.[lxxx] There is no evidence that Shoup considered withdraw that night.[lxxxi] No counterattack occurred due to Japanese command and control problems. The primary cause was that Admiral Shibasaki and his staff were killed while shifting the position of their headquarters during the afternoon,[lxxxii] and the Japanese communications were in shambles. A well organized counterattack would have been disastrous for the Marines,[lxxxiii] but it did not happen, even though the Japanese assembled over 1000 men to oppose the Marines on day two.[lxxxiv] Had Shibasaki lived and the Japanese communications survived, a counterattack might have had ramifications far beyond Tarawa.[lxxxv]

Day Two

Advancing Under Fire

The second day began with the First Battalion EighthMarines landing on Red Two, while the 6th Marines began to land on Green Beach at the far western tip of Betio. Like the Marines who landed on the first day, 1/8’s landing turned into a bloodbath, the tide fell even lower than the previous day. As they hit the reef and waded ashore they drifted into some of the heaviest Japanese defenses. Japanese guns, including the dual 5.5” guns took direct aim at the boats, while Marines ashore watched helplessly. War correspondent Robert Sherrod noted: “This is worse, far worse than it was yesterday.”[lxxxvi] Only half of 1/8 reached the beach with none of their heavy weapons or equipment. Shoup ordered the remnants of the battalion into line on his western flank in preparation for an advance inland.[lxxxvii] During five hours of landings on day two, the “Marine casualties reached a higher rate than that sustained on the first morning.”[lxxxviii]

Meanwhile, Shoup ordered Ryan’s “orphans” to make an attack down the right flank of the Japanese positions on Green Beach. Shoup’s decision and Ryan’s leadership made the attack a success. The “American victory at Betio evolved from the attack during one intense hour the second morning.”[lxxxix]

Taking every available Marine, two surviving Sherman tanks, and some mortars, Ryan gathered his force and coordinated Naval Gunfire support. The area contained a number of heavy guns including two of the remaining 8” mounts. A destroyer blanketed the Japanese positions with 5” shells and fire from her light AA guns.[xc] Attacking behind the beach, Ryan’s Marines isolated and destroyed everyone and everything that looked hostile.[xci] Against minimal opposition Ryan’s Marines quickly seized the gun positions and the western end of the airfield. Within an hour his Marines occupied the entire western side of Betio up to a 200 yard depth. At 1200 he radioed Shoup to let him know the good news, and that he now intended to advance east against the airfield.[xcii] The attack allowed the Marines to land intact battalions with supporting arms for the first time battle.[xciii]

To the east behind Red Two and Red- Three, the 8th Marines and survivors of 1/2 and 2/2 attacked against fierce Japanese opposition near Shibasaki’s former command bunker and two other large bunkers which were mutually supporting. The attack by the 2nd Marine survivors eventually succeeded in getting completely across the south side of the island.[xciv] During the attack Lt. Hawkins of the Scout Snipers, who had distinguished himself at the pier the previous day was mortally wounded.

The attack cut the island in two, but the Japanese launched a viscous counterattack on the Marine positions which was beaten back.[xcv] The 8th Marines faced a more difficult task going against what was now the heart of the Japanese defense as the defenders had been reinforced by Lt. Minami and his third company of the 7th Special Naval Landing Force.

Vicious fighting ensued and by nightfall “the Marines had little to show for their heavy losses,[xcvi] but they did make significant inroads against the Japanese to warrant optimism for D+2.[xcvii] By evening the Marines on Red-1 and Red-2 had consolidated their beachhead so that reinforcements were finally able to land, including jeeps, artillery and heavy equipment.

By mid-day the Marines noted that Japanese defenders were beginning to commit suicide, and they began to feel that Japanese morale had broken. By late afternoon Shoup transmitted the message: “Casualties many. Percentage of dead unknown. Combat efficiency-We are winning.”[xcviii] By late afternoon Major Jones’s First Battalion Sixth Marines landed on Green beach in their rubber boats, reinforcing Ryan’s orphans. It was the first of the 7 battalions on the island to get ashore intact.

Ryan and Jones coordinated their units for a night defense and an early attack the next morning.[xcix] Meanwhile, Second Battalion Sixth Marines cleared the nearby island of Bairiki, allowing the artillery of Second Battalion Tenth Marines to land its howitzers on the island. This in cut off any line of retreat for the defenders of Betio.[c] Colonel Merritt Edson came ashore during the evening to relieve Shoup[ci], who remained to help coordinate the next day’s attack. Once again there were no coordinated Japanese counterattacks. The senior officer, Commander Takes Sugai, was isolated in the pocket between the Red and Green beaches, and no senior officer could coordinate any attacks.[cii]

Mopping Up: Day Three and Four

Wrecked LVT’s and Dead Marines Litter the Beach

Day three began with attacks against Japanese strong points and the arrival of more reinforcements, including 3/6 which landed on Green Beach, and three light tank platoons which landed on Red-2.[ciii] The Marines attacked from Green Beach, sweeping east to join the 2nd Marines who had cut the island in two the day before. The 8th Marines continued to attack the heavily fortified bunker complex, and eventually captured the heavily fortified and defended positions.

During the assault First Lieutenant Sandy Bonnyman of 1/18 won the Medal of Honor for leading the assault on these positions, including destroying a major bunker defended by 150 Japanese, he was killed during the fight.[civ] Fighting remained fierce throughout the day and General Smith arrived to take command on shore. The Marines continued to attack supported by tanks, artillery and naval gunfire. By the evening they were established at the east end of the airfield.

The now desperate Japanese defenders launched a series of Banzai charges which beginning about 1930 hours and ending about 0400 when the Marines annihilated the last attack with the assistance of artillery.[cv] The attack, which could have succeeded the first or early the second day, now aided the Marines by killing troops that might have been used to exact a higher price in Marine lives for the tail of the island.[cvi]

The next morning the Marines pushed forward and eliminated the last Japanese defenders, and by 1200 Betio was secured. Of about 5000 defenders only 17 Japanese and some Korean laborers were taken prisoner.[cvii] The Marines lost over 1000 killed and 2300 wounded.[cviii]

One of the Japanese Survivors being Interrogated

Epilogue

The Marines paid a heavy price for Betio, but it was not to be a useless sacrifice. However, it was a source of great controversy especially among politicians.[cix] Historian Ronald Spector wonders if waiting for better tides or a full moon would have saved lives.[cx] Holland Smith later argued that Tarawa should have been bypassed, but Nimitz’s biographer, E. B. Potter notes “if the lessons of the amphibious assault had not been learned at Tarawa, they would have to be learned elsewhere, probably at greater cost.”[cxi]

The lessons learned aided all future amphibious operations in the Central Pacific and elsewhere. Timing and coordination of naval gunfire support, air strikes and combat loading of transports were all refined in future operations. Large numbers of armored and up-gunned Amtracks would be part of every future operation.[cxii] Intelligence was emphasized and replicas of the Japanese fortifications were built and tested to determine the best way of destroying them.[cxiii] Likewis, the Marines shocked the public by releasing photos and films of the carnage on Tarawa to awaken them to the challenges ahead.[cxiv]

Today the battle is remembered annually by the 2nd Marine Division at Camp LeJeune, North Carolina. Each year, an ever shrinking number of veterans of the battle attend the ceremonies. Samuel Eliot Morison put it best: “All honor, then, to the fighting heart of the United States Marine. Let the battle for that small stretch of coral sand called Betio of Tarawa be remembered as terrible indeed, but glorious, and the seedbed for victory in 1945.”[cxv]

Appendix: The Commanders

Lieutenant General Holland Smith and Major General Julian Smith

General Holland M. “Howling Mad” Smith USMC: (1882-1967) Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith commanded V Amphibious Corps during the Gilberts operation. Prior to the war he had worked extensively on amphibious warfare doctrine for both the Marine Corps and Navy. Unlike many senior officers Smith was not a Naval Academy graduate having matriculated from the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) in 1903 and law school in 1903. Smith served as Adjutant of the 4th Marine Brigade in the First World War and served in Panama and the Dominican Republic in addition to other Marine tours afloat and ashore. He served well and had many key assignments between the wars culminating in as the Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps. Subsequent to the Gilbert campaign he served as Commanding General of the Fleet Marine Force, Pacific and later commanded the Marines at Iwo Jima. He retired in 1946.

Major General Julian Smith USMC: (1885-1975) Major General Julian Smith served as Commanding General 2nd Marine Division at Tarawa. He graduated from the University of Delaware and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in 1909. He served in Haiti, Santo Domingo and the Vera Cruz expedition. During the First World War he served as an instructor in the Marine Officer training camps at Quantico. After the war he served in Cuba, Nicaragua and various command and staff posts including the Army Command and General Staff College. He commanded 5th Marines in 1938 and in 1942 was promoted the Major General serving as director of Fleet Marine Force Schools, New River, NC. He took command of 2nd Marine Division in May 1943 and served there until April 1944 when he became Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops, Third Fleet and in December 1944 took command of the Military Department of the Pacific. He retired in 1946.

Colonel David Shoup

Colonel David Shoup USMC: (1904-1983) Colonel David Shoup commanded the 2nd Marines at Tarawa, being appointed as commander when its commander fell ill. Shoup won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions on Tarawa. A 1926 graduate of DePauw University, Shoup was commissioned a Second Lieutenant through the ROTC program that year. He served in various assignments to include service in China, at sea on the battleship Maryland and Marine Barracks Puget Sound Navy Yard. He joined the staff of 6th Marines in October 1940 and assumed command of 2/6 in February 1942. He was assigned as the Assistant Operations Officer for 2nd Marine Division in July 1942 and promoted the Lieutenant Colonel. He went with the Division to New Zealand where he became the G-3 and from which he was fleeted up to command 2ndMarines at Tarawa. After Tarawa he served as the Division Chief of Staff at Saipan and Tinian. After the war Shoup continued to be assigned in key billets at the Pentagon and as commanding General, 1st Marine Division and then the Third Marine Division. He became Chief of Staff, Headquarters Marine Corps in 1958 and was appointed as the 22nd Commandant of the Marine Corps by President Eisenhower, a post that he retained until his retirement in 1963.

Rear Admiral Tomanari Sachiro

Admiral Tomanari Sachiro IJN: (1887-?) Commander of Tarawa garrison until relieved by Rear Admiral Shibasaki. Graduate Naval Academy 1910, initially a communications officer he held various commands including three destroyers, an Oiler, the Light Cruiser Yuma, Heavy Cruisers, Furutake and, Haguro and the Battleship Kirishima. Assigned to Tarawa in February 1943, he helped design and supervised the initial construction of the defenses until he was relieved by Admiral Shibasaki on 20 July1943. He returned to Japan and served the remainder of the war on Navy Division of Imperial General Headquarters. Tomonari survived the war though nothing is mentioned as to his postwar fate.

Rear Admiral Shibasaki Keiji

Rear Admiral Shibasaki Keiji IJN: (1894-1943) Commanded Tarawa Garrison until his death during the battle. He graduated from the Naval Academy in 1915 and he was a skilled navigator and instructor. Prior to the war he had served afloat and ashore and ashore and had commanded a ship and naval station and served as a naval attaché to Prince Kuni Asaakira, a member of the Imperial Family. Among his assignments was 19 month combat tour with the special Naval Landing Forces in China, where he served as Chief of Staff of Shanghai Special Naval Landing Force. Shibasaki’s leadership helped the garrison improve their defensive capabilities and combat skills as he inspired them to great heights and executed an intense training program. He was killed in the battle.

A Personal Note

I have not been to Tarawa but feel that I know it well. I served in Second Marine Division from April 1999 through December 2001. Due to my prior service experience I was used to fill gaps where chaplains were needed and ended up serving in four different battalions. I served in 2nd Combat Engineer Battalion, the descendant of 1/18, the combat engineers. We had a WWII Bulldozer outside our command post named after Sergeant Bordelon, the Medal of Honor Citations for Bordelon and Boonyman were prominently displayed. I also served in 1/8 and 3/8. I knew the accounts of the slaughter of these Marines as they attempted to land but as I re-read the accounts I was moved by their courage under fire. The CPs of these battalions are also adorned with citations of their heroes lost at Tarawa. Veterans would visit our units during Tarawa Days at Camp LeJeune, worn by the battle and the years they always made a great impression on me.

There is almost a mystical connection between the Second Marine Division and the Marines of Tarawa; it was a crucible that defined the division, whose motto is the same as the Army Infantry School. “Follow Me!”

Semper Fidelis,

Padre Steve+

Notes

[i] Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. The Free Press, New York, NY 1985. p.253

[ii] Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2000. p.338

[iii] Ibid. Spector. p.253

[iv] Ibid. p.255 The conference also set a date for the invasion of France.

[v] Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945. Random House, Inc. New York, NY 1970. p.468

[vi] Ibid. Spector. p.255

[vii] Costello, John. The Pacific War 1941-1945. Quill Publishing, New York, NY 1982. p.430

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Potter, E.B. Nimitz. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1976, Third Printing with Revisions 1979. p.243. Nimitz’s forces would have had to seize 5 major Japanese bases and his staff was not sure that the Pacific carrier force would be strong or experienced enough to provide the necessary air cover for the operation.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid. pp.243-245

[xii] Morison, Samuel Elliott. The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War. Little Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto, 1963. p.296.

[xiii] Hammell, Eric and Lane, John E. Bloody Tarawa: The 2nd Marine Division, November 20-23, 1943. The Zenith Press, St. Paul MN 2006. Text copyright 1998 Eric Hammell and John E. Lane. p.4

[xiv] See Alexander, Joseph H. Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa.Ivy Books, published by Ballantine Books, New York, NY. 1995. pp. 39-40. This unit became the Third Special Base Unit on its deployment and was joined by the 111th Construction Battalion.

[xv] Ibid. Hammell. p.4

[xvi] See Alexander pp.39-40. This unit was basically a reinforced infantry battalion with 3 rifle companies, a weapons battery, anti-aircraft battery, a light tank company and support units numbering about1600 men.

[xvii] Ibid. Alexander. p.43

[xviii] Alexander p.27 The Rikusentai was the Japanese equivalent of Marines, who numbered about 50,000 men. The officers attended Army schools and qualified enlisted men attended additional Army specialist training.

[xix] Ibid. Costello. p.431

[xx] Ibid. Hammell. p.22

[xxi] See Alexander p.77. While most writers say that these guns were brought from Singapore, Alexander notes that British writer William H Bartsch submitted proof (serial numbers) that the guns were sold by Vickers to Japan in 1905 as a legitimate business transaction.

[xxii] These are the same guns (127mm) mounted as the secondary armament of Nachi and Takao Class Heavy Cruisers and later mounted on light cruisers to replace the main battery with a more effective anti-aircraft armament.

[xxiii] Ibid. Hammell. p.22

[xxiv] Hammell notes that many of these bunkers and pillboxes were so well concealed that they could not be seen.

[xxv] Ibid. Toland. p.469.

[xxvi] Ibid. Alexander. p.43.

[xxvii] Ibid. Hammell. p.28

[xxviii] Ibid. Morison. p.297

[xxix] Ibid. Costello. p.429

[xxx] At this point the force could provide everything except major permanent repairs to warships.

[xxxi] Liddell-Hart, B.H. History of the Second World War. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, NY 1970. p.511

[xxxii] Ibid. Costello. p.431

[xxxiii] The older LVT-1s had boiler plate armor added as a field modification and were given a heavy machine gun. Prior to this they were unarmored and had two light machine guns.

[xxxiv] Ibid. Morison. p.303

[xxxv] Hammell includes a by name list of these officers in Appendix B. Of note for today, each MEUSOC (Marine Expeditionary Unit, Special Operations Capable) has an assigned Naval Gunfire Support Team.

[xxxvi] Ibid. Alexander. pp. 61-62. The Shermans had to be transported aboard pre-loaded LCM-3s carried in the well decks of the LSDs.

[xxxvii] Ibid. Alexander. pp.58-59

[xxxviii] Ibid. Morison. p.297. As a sidebar discussion it should be noted that Galvanic helped provide the model for the organization of all further Marine Corps amphibious doctrine now known by the acronym PERMA; Planning, Embarkation, Rehearsal, Movement and Assault, which describes the 5 phases of a amphibious assault.

[xxxix] Ibid. Hammell details the intricacies of the particular tides seen at Tarawa and the knowledge that the Marines had from the former Resident Commissioner of the Island, Major Frank Holland who warned the division staff that he knew that there would not be enough water over the reef to get landing craft across it. (pp.18-20)

[xl] Ibid. Alexander. pp.75-77

[xli] Ibid. Alexander. pp.67-68.

[xlii] Ibid. p.70

[xliii] Ibid. p.71

[xliv] Ibid. Morison. p.302

[xlv] Ibid. Hammell. p.16

[xlvi] Johnston, Richard W. Follow Me! The Story of the Second Marine Division in world War II. Copyright 1948 by the Second Marine Division History Board and published by Random House Publishers, New York, NY 1948. p.106

[xlvii] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. p.511 Johnson says 2,700 tons. (p.106)

[xlviii] Ibid. Johnston. p.106

[xlix] Ibid. Hammell. p.17

[l] Ibid.

[li] Ibid.. Hammell. 46-47

[lii] Ibid. Morison. p.303

[liii] Ibid. Alexander. p.113. Alexander notes that the Japanese would have been better served by using these guns on the stalled out landing craft.

[liv] Ibid. Hammell. p.47.

[lv] Ibid. Hammell. p.58

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] Ibid. Morison. p.303

[lviii] Ibid. Alexander. p.79

[lix] Ibid. Hammell. p.17

[lx] Ibid. Alexander. p.121

[lxi] Wukovits, John. One Square Mile of Hell: The Battle for Tarawa. NAL Caliber, published by New American Library, a division of Penguin Group USA, New York NY, 2006. p.112

[lxii] Ibid. Johnston. p.116

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Ibid. Wukovits. P.119 Other companies suffered as grievously, K/3/2 was not alone in its suffering.

[lxv] Ibid. Spector. pp.263-264

[lxvi] Ibid. Alexander. pp.136-138

[lxvii] Ibid. Hammell. p.90

[lxviii] Ibid. p.95

[lxix] Ibid. Spector. p.264

[lxx] Ibid. Wukovits. p.114

[lxxi] Ibid. Alexander. pp.139-140

[lxxii] 1/8 did not arrive on the beach due to botched communications until D plus 1.

[lxxiii] Ibid. p.150 The last time this signal had been sent it was by Major Devereaux at Wake Isalnd

[lxxiv] Ibid. p.151

[lxxv] Ibid. Johnston. p.132

[lxxvi] Ibid. Hammell. p.112

[lxxvii] Ibid. p.130

[lxxviii] Ibid. Johnston. p.122

[lxxix] Ibid. Johnston. p.122

[lxxx] Ibid. Costello. p.436

[lxxxi] Ibid. Alexander. p.163

[lxxxii] Ibid. Alexander. pp.157-158 Hammell notes that Shibasaski was most likely killed by fire from Ringgold or Dashiell.

[lxxxiii] Ibid. Hammell.pp.139-140

[lxxxiv] Ibid. Alexander. p.162

[lxxxv] Ibid. Wukovits. p.176. Wukovits notes how this could have affected the planning for the Normandy invasion.

[lxxxvi] Ibid. Alexander. p.173

[lxxxvii] Ibid. Hammell. p.160

[lxxxviii] Ibid. Costello. p.437

[lxxxix] Ibid. Alexander. p.170

[xc] Ibid. Hammell. p.163

[xci] Ibid. Hammell. p.166

[xcii] Ibid. Wukovits. p.178

[xciii] Ibid. Alexander. p.170 Ryan would be awarded the Navy Cross for his efforts.

[xciv] Ibid. Hammell. p.172

[xcv] Ibid. Alexander. p.179

[xcvi] Ibid. Alexander. p.181

[xcvii] Ibid. Hammell. p.178

[xcviii] Ibid.. Wukovits. p.194

[xcix] Ibid. Hammell. p.202

[c] Ibid. Hammell. p.212

[ci] Shoup would be awarded the Medal of Honor and eventually go on to be the Commandant of the Marine Corps.

[cii] Ibid. Alexander. pp.191-192

[ciii] Ibid. Johnston. p.134 2 platoons landed on Red-2 and one on Green Beach.

[civ] Ibid. Alexander. pp.202-205

[cv] Ibid. Johnston. pp.145-146

[cvi] Ibid. Johnston. p.147

[cvii] Ibid. Toland. p.470

[cviii] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.345

[cix] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. p.511

[cx] Ibid. Spector. p.266

[cxi] Ibid. Potter. P.264

[cxii] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.347 The Amtrack in improved forms has been part of the Marines ever since. The current model serves in a traditional amphibious role as well as a Armored Personnel Carrier for Marines involved in ground combat operations ashore.

[cxiii] Ibid. Costello. p.439. The method found to work best was long range plunging fire by heavy guns found on battleships and heavy cruisers.

[cxiv] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.346

[cxv] Ibid. Morison. p.306

Bibliography

Alexander, Joseph H. Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa. Ivy Books, published by Ballantine Books, New York, NY. 1995.

Costello, John. The Pacific War 1941-1945. Quill Publishing, New York, NY 1982

Morison, Samuel Elliott. The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War. Little Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto, 1963

Hammell, Eric and Lane, John E. Bloody Tarawa: The 2nd Marine Division, November 20-23, 1943. The Zenith Press, St. Paul MN 2006.

Johnston, Richard W. Follow Me! The Story of the Second Marine Division in world War II. Copyright 1948 by the Second Marine Division History Board and published by Random House Publishers, New York, NY 1948

Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2000

Potter, E.B. Nimitz. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1976, Third Printing with Revisions 1979

Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. The Free Press, New York, NY 1985 Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945. Random House, Inc. New York, NY 1970