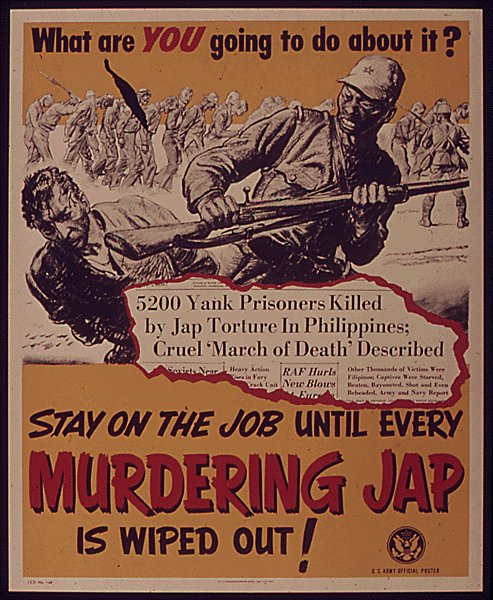

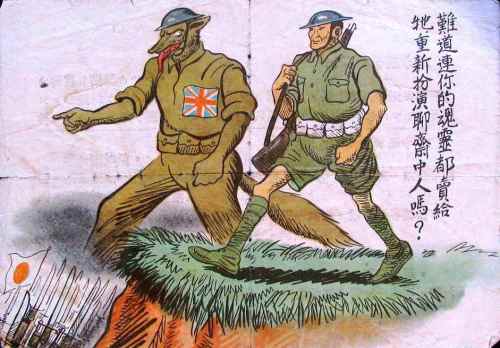

This is the next to last installment of my series “Background to “The Pacific” which deals with certain subjects themes and battles dealt with in the HBO series by that name. This article deals with the Okinawa campaign which is covered in part nine of the series. Like all battles in the Pacific which pitted Americans against Japanese Army and Naval Infantry forces this battle was fought often to the death and unlike other battles fought with a large civilian population in the battle area.

Plans and Preparations

The United States decided to invade Okinawa in the fall of 1944 following the seizure of Peleliu and the Philippine landings. The planned invasion of Formosa was cancelled after General Simon Bolivar Buckner objected.[i] Buckner argued that the Japanese army on it was “much too strong to be attacked by the forces by American Forces then available in the Pacific.”[ii] The strategic rationale behind the decision to invade Okinawa included Okinawa’s proximity to Japan as a staging base for a future invasion of the Japanese mainland. Likewise taking the island would severe Japan’s lines of communication and commerce with Southeast Asia and to serve as base for strategic bombers.[iii] Planning began in October 1944 and the detailed plan for OPERATION ICEBERG was issued 9 February 1945.[iv] The campaign was not planned in isolation but “was bound up strategically with the operations against Luzon and Iwo Jima; they were all calculated to maintain unremitting pressure against Japan and to effect the attrition of its military forces.”[v]

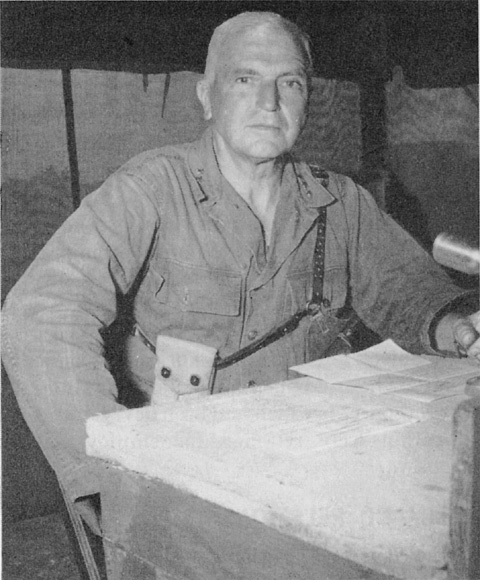

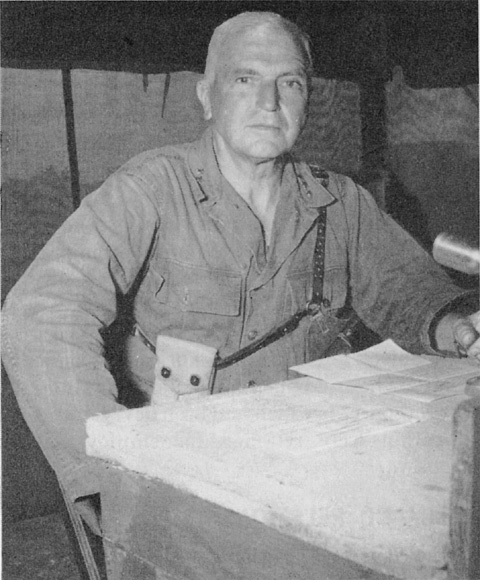

The Unfit American Commander Lt Gen Simon Bolivar Buckner chosen over veteran Marine Commander Lt Gen H M “Howling Mad” Smith

The War Department insisted that Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner command the newly formed 10th US Army.[vi] . Buckner was chosen to command based on his taking of the Aleutians, displacing the veteran Marine Holland M. Smith. One critical history noted that “compared to his subordinates, Buckner was hardly fit to command a corps, let alone a field army.”[vii]

The 10th Army consisted of the 3rd Amphibious Corps (1st, 2nd and 6th Marine Divisions) under Major General Roy Geiger and the XXIV Army Corps (7th, 27th, 77th and 96th Divisions) under Major General John Hodge.[viii] 2nd Marine Division was designated as a diversionary force, and the 77th Division was assigned to take the nearby island of Kerama Retto prior to the landings to provide the Navy a safe anchorage and as an artillery platform to shell Okinawa. The 27th Division was in corps reserve. All were veteran units and had it was believed they would be “more than enough to overwhelm the estimated 70,000 Japanese on Okinawa.”[ix] However, much of XXIV Corps had only been engaged in hard combat on Leyte and was not relieved of their duties on Leyte on 1 March 1945. This provided these units with no time to rest and refit.[x] More importantly badly needed troop replacements had been diverted to Europe due to the crisis in infantry strength there during the battle of the Bulge.[xi] The operation was very large and “mounted on a scale that matched the previous year’s Allied landing in Normandy.”[xii]

The Japanese Preparations

Japanese Commander Lt General Ushijima

American intelligence underestimated the number of Japanese on the island, with an estimate of 55,000 with the expectation of 66,000 by 1 April.[xiii] However by the time of the invasion the Japanese defenders numbered over 100,000.[xiv] The defense of Okinawa was entrusted to the 32nd Army was activated in 1 April 1944 commanded by Lieutenant General Ushijima. In addition to Okinawa the 32nd Army was responsible for the entire Ryukyu chain.[xv] General Ushijima had commanded an infantry group in Burma and was commander of the military academy when appointed to command 32nd Army and ordered to Okinawa. His Chief of Staff, General Cho was a firebrand. Cho had served in China and had participated in a number of attempted military coups in the 1930s as a member of the “Cherry Group.”[xvi] Another key officer though relatively junior was Colonel Yahara the Operations Officer. He had served as an exchange officer in the United States and was intellectual and a modern soldier. He viewed war as a science, won by “superior tactics adjusted to terrain, weapons and troops…not Banzai charges.”[xvii] He was “widely recognized as an expert in his field,”[xviii] and devised the Japanese defensive plan for Okinawa.

Colonel Yahara Architect of the Japanese Defensive Plan

Until 32nd Army was activated Okinawa was garrisoned by a mere 600 troops,[xix] and until major units arrived these soldiers concentrated on airfield construction.[xx] Eventually the 9th, 24th and 62nd Infantry Divisions, the 44th Mixed Brigade along with a light tank regiment and significant artillery came to Okinawa. Additional forces were alloted to outlying islands. The 24th Division was a triangular division of 3 infantry regiments of 3 battalions each and supporting arms. The 62nd Division was a “brigaded” division activated in 1943 was formed from the veteran 63rd and 64th brigades each with 4 infantry battalions and supporting arms. It had no organic artillery. Both of the brigades of this division received an additional infantry battalion in January 1945 giving the division ten maneuver battalions.[xxi] Okinawa’s defenses were significantly weakened when 9th Division was transferred to Formosa by the 10th Area Army in late 1944. To compensate General Ushijima converted Naval and service troops on the island into front line troops. Additionally he called the Okinawan Boeitai volunteers and conscripts into service.[xxii] The Boeitai numbered 20,000 and burned “with ardor to serve their emperor.”[xxiii] Seven sea raiding units were converted into infantry battalions.[xxiv] The major units, with the exception of 24th Division which had been transferred from Manchuria had combat experience.[xxv]

USS Tennessee Provides Naval Gunfire Support while LVTs Advance toward the Beaches

Ushijima’s plans to concentrate his forces in the south were delayed by Tokyo.[xxvi] Likewise the number and disposition of troops in the Ryukyu’s were decided by Imperial Headquarters.[xxvii] Colonel Yahara wrote that had Imperial Headquarters “been able to give us an overall plan with specific unit names and arrival dates, we would have been able to follow a consistent policy, disposing units in an efficient manner rather than moving them left and right.”[xxviii] He noted how the 44th Mixed Brigade had to change location and thus its defensive preparations “seven times during the ten months before the actual battle….”[xxix]

XXIV Corps Advancing South

The loss of the 9th Division and its 25,000 soldiers forced Ushijima to change his initial plan to defend the beaches and then launch a major counterattack to drive the Americans into the sea.[xxx] Ushijima decided to defend the south end of the island. This was the most defensible area, with a network of fortifications and underground caves centered on the ancient citadel of Shuri Castle. “Troop disposition would conform to local terrain; troop strength would be concentrated; and an extensive system of subterranean fortifications constructed.”[xxxi] The defenses were “anchored in natural and artificial caves which dotted the mountainous regions around Shuri.”[xxxii] “Terrain features were incorporated into the defense and weapons were well sited with excellent fields of fire.”[xxxiii] General Ushijima left Colonel Udo’s 2nd Infantry Unit to fight a delaying action in the north,[xxxiv] having decided that the area was of “little military value.”[xxxv] Likewise Ushijima decided not to contest the landings or to defend the airfields at Kadena and Yontan.[xxxvi] He planned to use Boeitai units to demolish the airfields when the Americans approached.[xxxvii]

Flamethrowers were Widely Employed their Operators were Targeted by the Japanese

Ushijima’s defensive scheme laid out by Yahara involved concentric defensive lines, tunnels and bunker systems and even the Chinese tombs which dotted the island were converted to pillboxes over the objections of Okinawan elders.[xxxviii] Yahara and Ushijima planned a battle of attrition with all artillery in the army concentrated on the southern end of Okinawa. Yahara believed the battle would be a “bitter yard-by-yard” defense of the island,[xxxix] with a focus on defense in depth with preparations for anti-tank warfare.

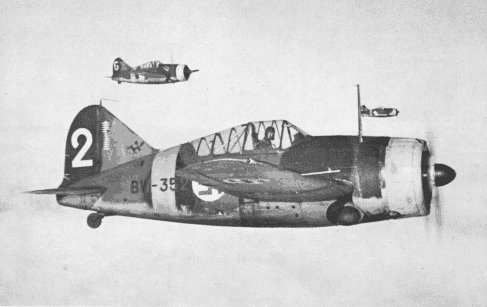

Kamikaze taking off

Kamikaze taking off

There were to be no Banzai charges.[xl] Ushijima turned Bushido “inside out” and urged his soldiers to “Devise combat method [sic] based on mathematical precision, then think about displaying your spiritual power.”[xli] The defenders would be assisted by suicide boat squadrons based on Okinawa and Kerama Retto and over 4000 aircraft, conventional and Kamikaze and a naval force built around the super battleship Yamato.[xlii]

The Landings

LVT’s going ashore at Okinawa

LVT’s going ashore at Okinawa

The assault on Okinawa began with landings by 77th Division on Kerama Retto on 26 March. The landings were met with little opposition as most of the combat troops on the islands had been moved to Okinawa leaving only base and service troops and members of a Sea Raiding Unit and Korean laborers to defend the small island.[xliii] By the 29th of March the islands were taken, along with numerous prisoners. Over 350 of the fast “Suicide Boats” that were to attack US transports and landing craft were destroyed at Kerama Retto and long range artillery was emplaced were it could support the Okinawa landings.[xliv] More importantly Kerama Retto provided the Navy a safe anchorage, and Service Squadron 10 arrived on 27 March to support naval forces around the island.[xlv] The naval bombardment was led by Admiral Deyo’s battleships and Admiral Blandy’s escort carriers[xlvi] and culminated on 1 April when 10th Army went ashore. By the time of the landing 10 battleships and 11 cruisers would join the attack.[xlvii] Over 13,000 large caliber shells were fired and a total of 5,162 tons of ammunition were expended on ground targets and 3,095 air sorties were flown by L Day.[xlviii] Fortunately for the Japanese Ushijima had listened to Colonel Yahara and elected not to defend the beach, and thus most of the shells fell on empty positions and terrain.[xlix]

Marines in LCVP going ashore

Marines in LCVP going ashore

The Americans landed on the Hagushi beaches adjacent to Kadena and Yontan air bases. No organized resistance was encountered and in the first hour 16,000 troops landed.[l] There was little disorganization and all units landed on time on the planned beaches.[li] The beaches were bisected by the Bishi River which served as the Corps boundary. The 1st and 6th Marine Divisions landed north of it and the 7th and 96th to the south.

Japanese Suicide Boat of which many were stationed on Okinawa and the surrounding islands

Japanese Suicide Boat of which many were stationed on Okinawa and the surrounding islands

The Marines chopped up the “Bimbo Butai” in their area many of whom melted back into the civilian population.[lii] The Americans moved rapidly inland and by nightfall over 60,000 Marines and Soldiers were ashore.[liii] As the landings were made the 2nd Marine Division conducted a demonstration off Minatoga on the east side of the Okinawa actually launching several waves of landing craft.[liv] On 2 April the operation was repeated which helped divert some Japanese attention off of the actual landings. Ushijima reported that the attempt “was complete foiled, with heavy losses to the enemy.”[lv] Some Marine veterans of Peleliu were jubilant at not having to land and some wondered what the Japanese were up to.[lvi]

Marine Battalion Commander Raising Flag over Shuri Castle

In the following days the two Marine divisions would race north and east while Army troops advanced cautiously to the south first encountering light opposition.[lvii] The 1st Marine Division cut the island in two on April 3rd and was allowed to clear the Katchin Peninsula which it took without opposition.[lviii] The 6th Marine Division moved north and by the 7th it had had taken Nago. Colonel Udo’s troops of the 2nd infantry Unit defended the Motubu with great skill[lix] but the Marines took the center of resistance on April 18th.[lx] They then cleared the remainder of the peninsula and the rest of the northern end of the island by the 20th.[lxi] The Marines had advanced 84 miles and killed 2,500 Japanese at the cost of 261 killed and 1,061 wounded. The Japanese survivors according to the plan of Colonel Udo afterward retreated into the hills and engaged in guerilla warfare.[lxii]

The Ordeal Begins

Demolition Team Advancing

As the Soldiers of the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions felt their way south, they began to encounter resistance from Japanese outposts. On 4 April 96th Division’s advanced elements including the 96th Recon Troop and 763rd Tank Battalion encountered the first Japanese anti-tank defenses, losing 3 tanks to well concealed 47mm anti-tank guns.[lxiii] The following day both the 7th and 96th divisions encountered more resistance and were held to minimal gains as they drove the Japanese out of their outpost positions.

Flamethrower tanks engaging Japanese positions

Flamethrower tanks engaging Japanese positions

On the 6th and 7th they captured “the Pinnacle” and “Cactus ridge” from elements of 3 independent infantry battalions which put up stiff resistance.[lxiv] By the end of 8 April against strong opposition XXIV Corps had suffered 1,510 battle casualties and was virtually halted.[lxv] Savage hand to hand fighting took place as the defenders worked to separate the American tanks from their infantry. They held the Americans outside the Shuri zone for 8 days.[lxvi]

Wrecked Tanks on Skyline Ridge

The 96th Division attacked the heavily defended Kakazu Ridge and Tombstone Ridge and was repulsed. The 7th Division was halted at Hill 178. The Japanese fought at close quarters and desperate hand to hand fighting “would characterize the Okinawa land battle.” While the Japanese infantry contested every yard “carefully concealed anti-tank guns seemed anchored into the terrain.”[lxvii] The deployment and concealment of the anti-tank guns helped nullify the American advantages in armor. The Japanese also employed 320mm spigot mortars[lxviii] and well sited machine guns and artillery sited on reverse slopes took a heavy toll of the attacking Americans. Of one company of 89 men which attacked Kakazu on 9 April “only three returned unwounded.”[lxix] Assisted by monsoon rains, “the Japanese turned every hill, every ridge into a bloody deathtrap.[lxx]

XXIV Corps Advancing South

On the 10th two regiments of 96th Division attempted a power drive with battalions advancing on line and were thrown back.[lxxi] The two divisions suffered 2.890 casualties in their abortive attacks while the Japanese lost close to 4,000, mainly to artillery fire.[lxxii] Ushijima’s defense planned by Yahara was “chillingly professional and efficient. Within a week the Japanese had stopped two very good Army divisions in their tracks.”[lxxiii] General Buckner paused sent for the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions and brought the 27th and 77th Divisions ashore to strengthen XXIV Corps.[lxxiv]

Counterattack

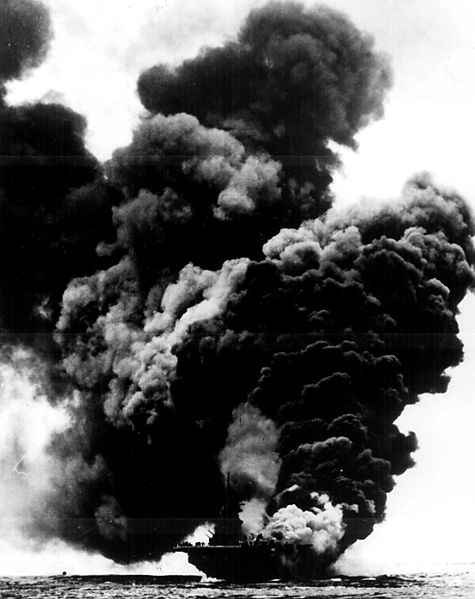

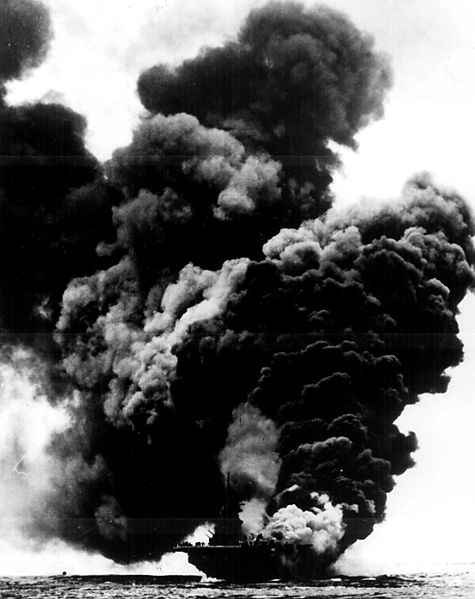

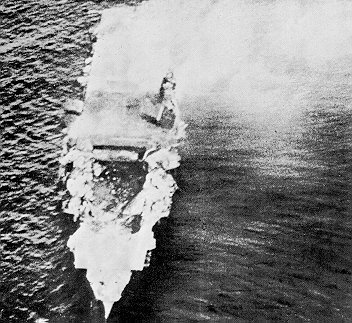

The War at Sea: Kamikaze Attack on USS Bunker Hill

It was at this point when “Yahara’s war of attrition was working well” that a division arose in the 32nd Army Staff, when General Cho; Ushijima’s Chief of Staff had “his first outburst of samurai offensive fever.”[lxxv] Cho noted the failure of the American attacks and believed reports that the American Navy had been heavily damaged by Japanese air power and by the reported success of Operation Ten-Go, the sortie of the Yamato and her escorts on their suicide mission. He based his optimism on a telegraph from Imperial Navy headquarters “claiming that Ten-go had been “very successful”[lxxvi] when in fact the Yamato and her escorts had been dispatched in hours by carrier aircraft with few American losses.

The Battleship Yamato Lead a 10 ship Suicide Task Force to Okinawa and was Sunk with Most of Her Crew

Below

USS Aaron Ward Damaged heavily damaged by Kamikaze Attack over 10,000 sailors were casualties including nearly 5000 dead due to Kamikaze attacks

Cho also assumed a reduction in the number of ships in the Hagushi anchorage and in the number of air sorties as signs of American weakness.[lxxvii] Cho persuaded Ushijima to launch a counterattack over the protestations of Yahara who argued that “it would waste men.”[lxxviii] The attack by four battalions of the 62nd and 24th Divisions began the night of 12-13 April. Based on infiltration tactics and supported by artillery the attack was badly planned and coordinated. One attack almost overran American positions on the draw on Kakazu Ridge, but the Japanese return to “bamboo spear tactics” exposing them to the “overwhelmingly superior America artillery fire….”[lxxix] The attack was a “total failure.”[lxxx]The Japanese lost nearly 1,600 men, half their force in an “operation ill conceived, understrength, misdirected, haphazard and uncoordinated.”[lxxxi]

Cracking the Outer Line

Reinforced by the 27th Division XXIV Corps prepared for another attack against the outlying Shuri defenses. In the interval between the Japanese attack and the new offensive the 77th Division landed on Ie Shima on 16 April and secured it on the 24th amid very heavy fighting killing over 4,700 Japanese, many armed civilians against the loss of 172 killed and 902 wounded Americans.[lxxxii] Among the American dead was legendary reporter Ernie Pyle.

Legendary Reporter Ernie Pyle with Marines. He would be killed on neighboring Ie Shima with the Army 77th Divison

Legendary Reporter Ernie Pyle with Marines. He would be killed on neighboring Ie Shima with the Army 77th Divison

The Americans aimed to penetrate the defenses and “seize the low valley linking Yonabaru on the east coast with the capital of Naha on the west.”[lxxxiii] The attack was supported by 27 battalions of artillery[lxxxiv] including 9 Marine artillery battalions.[lxxxv] Additional Naval gunfire support in the form of 6 battleships, 6 cruisers and 9 destroyers added to the rain of steel unleashed on the Japanese.[lxxxvi] Morison notes that Army historians stated that “Naval gunfire…was employed in greater quantities in the battle for Okinawa than in any other in history.”[lxxxvii]

USS Maryland contributes her firepower to support ground forces

USS Maryland contributes her firepower to support ground forces

The 7th Division was to take Hill 178 and drive south to the Naha Yonabaru road. 96th Division minus the 383rd Infantry was to “drive straight through the heart of the Shuri defenses seizing the town of Shuri and the highway beyond.” 27th Division attacking 50 minutes later to take advantage of artillery was to take Kakazu ridge and the coast plain north of Naha.[lxxxviii]

The attack began on April 19th and was preceded by a 19,000 shell bombardment.[lxxxix] Ushijima wisely ordered his men to remain in their caves. The Corps Artillery commander “doubted as many as 190 Japanese…had been killed in the bombardment.”[xc] The attack was immediately halted all along the line, gains, where there were any were measured in yards. Over 750 casualties were inflicted by the Japanese on the corps and 27th Division’s tank battalion lost 22 of 30 tanks to well positioned 47mm anti-tank guns.[xci] Buckner rejected the requests of the Corps commander Hodge and the Marine divisional commanders,[xcii] to launch a flanking amphibious operation at Minatoga with the 2nd Marine Division, and continued the frontal attacks. John Toland writing of the rejection of the amphibious operation noted that Ushijima “feared such a maneuver (“It would bring a prompt end to the fighting”) and had already been forced to move his “rear guard division north to beef up the Shuri line.”[xciii] Thus the three divisions continued to press their attacks, suffering heavy casualties. Eventually the Americans forced the Japanese off Skyline ridge[xciv] though the Japanese still held Kakazu.[xcv] When the 27th Division attacked again it found Kakazu abandoned by the Japanese.[xcvi] By the 24th Ushijima’s line was “pierced in so many places that it was in danger of collapsing….So General Ushijima withdrew to his next chain of defenses.”[xcvii] On April 30th the 1st Marine Division relieved the battered 27th Division which had suffered 2,661 casualties in less than two weeks.”[xcviii] The 1st Marine Regiment launched an attack on 1 May and was driven back with heavy causalities.[xcix]

General Cho’s Final Offensive

Knocked out Japanese tank from General Cho’s failed counter attack

Knocked out Japanese tank from General Cho’s failed counter attack

General Cho supported by 62nd Division’s commander, General Fujioka persuaded Ushijima over the strenuous objections of Yahara to launch a counter-offensive with the intention of isolating and annihilating the 1st Marine Division and “rolling up” XXIV Corps.[c] The attack was to occur along the entire line and include an amphibious landing behind American lines.[ci] The 62nd Division would take the lead as it had been less heavily engaged than 24th Division.[cii] Yahara argued his case strongly and warned the Ushijima that to attack “is reckless and will lead to an early defeat.”[ciii] The attack began on the night of 3 May and the forces making the amphibious landing were annihilated by the Marines.[civ] The Japanese made little headway during the main attack; one battalion achieved a small penetration of American lines at Tanabaru but was eliminated the next day.[cv] The Japanese 27th Tank Regiment lost most of its tanks and those remaining were used as “stationary artillery and pillboxes.”[cvi] The Japanese lost about 5,000 troops in the offensive.[cvii] Ushijima halted it and told Yahara “as you predicted this offensive has been a total failure. Your judgment was correct….” He ordered Yahara “to do whatever you feel is necessary.”[cviii] Cho saw “no hope at all”[cix] and asked Yahara jokingly “when will it be okay for me to commit hari-kari?” [cx]

Göttdammerung

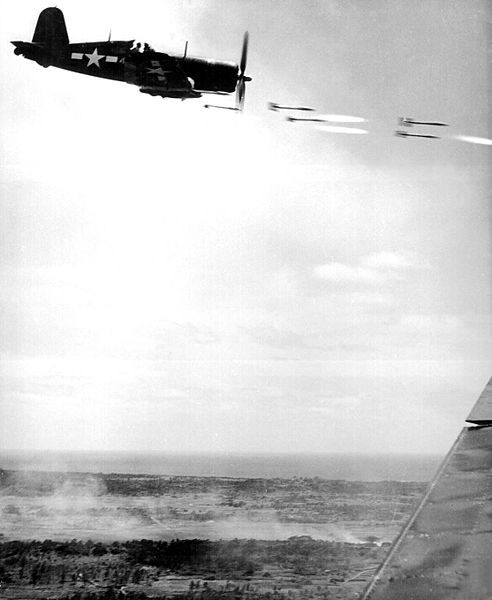

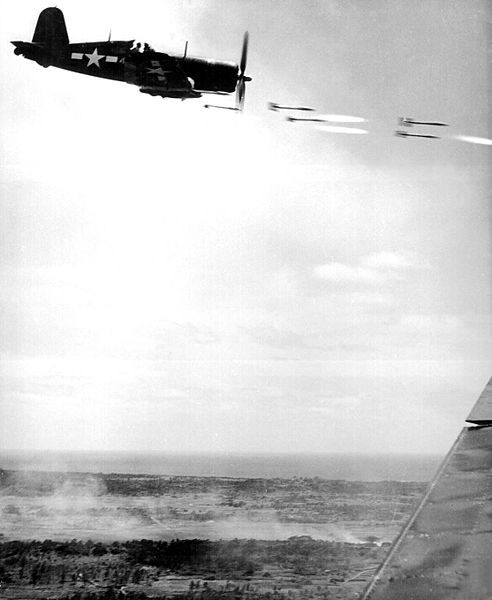

Marine F4FU Corsair providing close air support on Okinawa

Marine F4FU Corsair providing close air support on Okinawa

The American offensive resumed on 11 May and amid stubborn Japanese defense and heavy rains which hindered movement. The 1st and 6th Marine Divisions[cxi] and the 77th and the 96th infantry divisions attacked along the line but the primary objective was Shuri.[cxii] The Americans continued to apply pressure and make small gains against strong Japanese resistance put up by the 44th Mixed Brigade. The defense was particularly strong on Sugar Loaf Hill[cxiii] which cost 6th Marine Division nearly 4,000 total casualties before it was cleared out on 21 May.[cxiv] The 96th Division turned the Japanese east flank at Conical Hill on the 13th [cxv] while the First Marine Division cracked through the Japanese lines at Dakeshi Ridge.

Marines attacking Dakeshi Ridge

Marines attacking Dakeshi Ridge

It fought through Wana Ridge[cxvi] and engaged the Japanese in a costly battle in the Wana Draw. The 2nd Battalion 5th Marines supported by 30 tanks blasted their way through the draw, again against brutal Japanese resistance.[cxvii] On the 22nd Yahara persuaded Ushijima to withdraw from Shuri to the Kiyan Peninsula.[cxviii] The 1st Battalion 5th Marines crossed the divisional boundary of 77th Division to capture Shuri Castle on 24 May.[cxix] The Company commander, from South Carolina who took it did not have an American flag so he “substituted the flag of the Confederacy, a banner that he…carried in his helmet.” [cxx] Two days later the American flag was raised along with the standard of the 1st Marine Division in full view of the Japanese.[cxxi]

Tank infantry attack

Tank infantry attack

Following the Japanese withdraw from Shuri the battle continued with heavy rains hampering both sides, especially the more vehicle dependant Americans.[cxxii] The 6th Marine Division cleared the Oruku Peninsula south of Naha the first two weeks of June[cxxiii] killing 5,000 of the Japanese Navy defenders at a cost of 1,608 Marines. The Japanese resistance crumbled when Admiral Ota committed suicide and many defenders fled while others surrendered.[cxxiv] 7th Division pushed onto the Chinen Peninsula and 1st Marine and both 77th and 96th Infantry Divisions pushed steadily south against Japanese rear-guards.[cxxv] The 8th Marines from 2nd Marine Division were brought to the island to reinforce the depleted 3rd Amphibious Corps[cxxvi] A hard fight was fought along the Kunishi-Yuza-Yaeju escarpment where the Japanese conducted their last organized defense.[cxxvii] By the 17th the “32nd Army was dazed and shattered. Discipline had evaporated.”[cxxviii] The 32nd Army’s discipline and morale collapsed, and it “degenerated into a mob.”[cxxix] Yahara noted that “naturally, morale is low at the end of a battle, but we had never experienced anything like this.”[cxxx]

Lt General Buckner (Right) Observing 8th Marines Assault minutes before Being Killed

General Buckner was killed while observing 8th Marines attack Kunishi on the 18th and was succeeded by General Geiger of the Marine amphibious corps.[cxxxi] A final message from Tokyo congratulated 32nd Army on its achievements on the 20th.[cxxxii] General Ushijima and General Cho committed Hari-Kari early on the 23rd after ordering Yahara not to do so. Cho told Yahara “to bear witness as to how I died.”[cxxxiii]

Lt Gen Roy Geiger would take command of 10th Army becoming the first Marine ever to command a US Army field Army

Lt Gen Roy Geiger would take command of 10th Army becoming the first Marine ever to command a US Army field Army

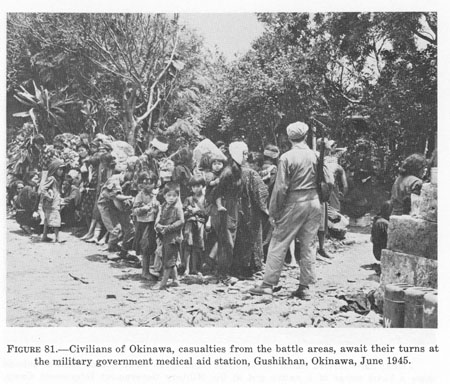

American battle casualties totaled 49,151 including 12,520 dead.[cxxxiv] The Japanese lost over 110,000 killed and 7,400 taken prisoner by the Americans.[cxxxv] About 75,000 Okinawan civilians were killed.[cxxxvi] Small numbers of Japanese renegades and Okinawan rebels conducted low-level guerilla operations until 1947.[cxxxvii]

Analysis

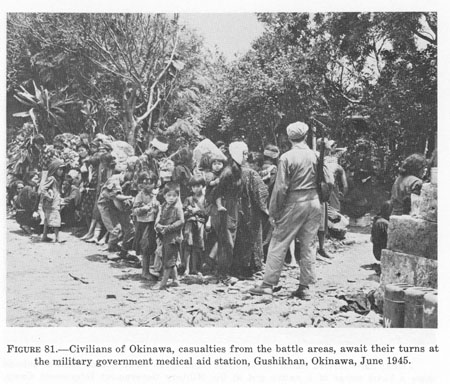

Civilian casualties (above) and prisoners (below) the prisoners chose capture over throwing themselves down “Suicide Cliff”

Civilian casualties (above) and prisoners (below) the prisoners chose capture over throwing themselves down “Suicide Cliff”

The key Japanese mistake occurred at the strategic level when 9th Division was transferred off the island[cxxxviii] and no further reinforcements were sent. With these forces Ushijima might have been able to hold out until the end of hostilities. Yahara criticized Imperial Headquarters which panicked when the landings occurred and ordered a counterattack which “left our army in utter confusion.”[cxxxix] General Ushijima’s major mistakes during the battle were the two costly offensives urged by General Cho against the protest of Colonel Yahara. These attacks sacrificed of some of his best troops for no effect and significantly weakened the 32nd Army’s defensive posture. Yahara objected to both of these offensives. According to the American intelligence debriefing Yahara considered the May 4th offensive “as the decisive action of the campaign.”[cxl] Gordon Rottman simply called that attack a “blunder.”[cxli]

On the American side Buckner fought an unimaginative and uninspired battle, much like Mark Clark’s Italian campaign or Courtney Hodges at the Huertgen Forrest. Murray and Millett, note that Buckner’s “flawed generalship contributed to the slaughter.”[cxlii] Buckner’s decision not to land the 2nd Marine Division or the 77th Division at Minatoga surrendered his one opportunity to maneuver against the Japanese to force them out of their prepared positions.[cxliii] Ronald Spector notes that “in retrospect Buckner ought to have given more consideration to an amphibious attack[cxliv] while Murray and Millett state that Buckner “did not have the experience to make such a critical decision.”[cxlv] Nimitz wondered if “the Army was using slow, methodical tactics to save the lives of soldiers at the expense of the Navy”[cxlvi] which was exposed to Kamikaze attacks as they had to continue to provide the close in support to 10th Army. Buckner’s rejection of this opportunity left him with the straight ahead attack. Another option which was available to Buckner was to seal off the Japanese and let them wither on the vine. Such an action in effect would have bypasses the Japanese defenders and force them to make Banzai attacks against dug in Americans.[cxlvii] The Americans had the airfields on day one and most of the key facilities needed for future operations and there was little to gain by continuing offensive operations in the south. Sealing off the Japanese would have certainly caused the Americans fewer casualties than the strategy which Buckner employed.[cxlviii]

The Human Cost of War: Marine Colonel Fenton prays for his Fallen Son

Buckner’s leadership was poor his strategy and tactics both unimaginative and foolish bordering on incompetent. In a time when American infantry replacements were tapped out and no new Infantry divisions were available for action he decimated good formations by throwing them into frontal attacks against well prepared fortified positions manned by experienced troops. Had Ushijima not followed General Cho’s advice squandering is own troops the battle would have cost even more American lives with the invasion of Japan looming. The War Department in its attempt to wrest control of an operation that should have remained under the control of the Navy and Marine Corps put the wrong man in the job when other more competent corps commanders such as General “Lighting Joe” Collins who had finished off the Japanese at Guadalcanal were available with European hostilities winding down. Why Buckner was chosen despite his incredibly limited command experience serving in the relatively inactive Aleutians and not even commanding a company in World War One had to be due to Army politics and in the end it cost nearly 50,000 American casualties on the land alone, not counting Navy casualties which totaled almost 10,000 including over 4,900 dead. The capture of Okinawa provided the Americans with valuable anchorages and airfields close to Japan had there been an invasion of the home islands, but they were obtained at great cost.

Notes

[i] Appleman, Roy, E., Burns, James M., Gugeler, Russell A., and Stevens, John. The United States Army in World War II, The War In the Pacific. Okinawa: The Last Battle, Center of Military History, United States Army. Washington DC. 1948. p.4

[ii] Leckie, Robert. Okinawa: the Last Battle in the Pacific Penguin Books, New York NY 1996. p.2. Although not mentioned by Leckie this shortage of forces was due to the American decision to limit the Army to 90 Divisions with dire consequences in Europe and Asia especially in the number of infantry available. For a good account of the impact of this see Russell Weigley’s Eisenhower’s Lieutenants.

[iii] Willmont, H.P. The Second World War in the Far East. John Keegan General Editor. Cassell Books, London, 1999. p.186.

[iv] Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War. An Atlantic Monthly Press Book, Boston MA 1963. p.525

[v] Ibid. Appleman. p.4

[vi] Costello, John. The Pacific War: 1941-1945 Quill Publishers, New York, NY 1981. p.554.

[vii] Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War. The Belknap Press of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. 2000. p.515

[viii] Ibid. Leckie. pp. 53-54. Note Costello misidentifies both of these corps calling them 3rd Marine Corps and XIV Army Corps. He also does not count the 77th Division in his figures.

[ix] Ibid. Costello. pp. 554-555. Costello’s figures are slightly above the official estimates listed below.

[x] Ibid. Leckie. p.56

[xi] Ibid. Leckie. p.57 An important point to note is that the Army had reached a critical point in its ability to conduct the war. The steady drain on infantry strength that began in Normandy was heightened in the Huertgen Forrest and the Bulge.

[xii] Ibid. Costello. p.556

[xiii] Ibid. Appleman. p.15

[xiv] Ibid. Costello. p.555

[xv] Yahara, Hiromichi. The Battle for Okinawa. Introduction and Forward by Frank Gibney. Translated by Frank Pineau and Masatoshi Uehara. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY. 1995. p.3

[xvi] Rottman, Gordon R. Okinawa 1945: The Last Battle. Osprey Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2002. p.35

[xvii] Ibid. Leckie. pp.31-32

[xviii] Ibid. Rottman. p.37

[xix] Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945. Random House, New York, NY 1970. p.683.

[xx] Ibid. Yahara. p.7

[xxi] Ibid. Rottman. Pp.47-48

[xxii] Ibid. Toland. pp.683-684. Yahara also notes the arrival of the 15th Mixed Brigade and the fact that the Japanese considered the 44th Mixed Brigade “one of our Army’s prized units.” (p.12)

[xxiii] Ibid. Toland. p.683. Leckie comments on the low opinion of many Japanese soldiers about the Boeitai calling them Bimbo Butai (Poor Detachment), as the most of the Japanese had come to loathe Okinawa and all things Okinawan. A comment from my own service in Okinawa in 2000-2001 is that this loathing of Okinawa by Japanese is still common, Japanese tend to look down on Okinawans and the Okinawans now tend to resent the Japanese.

[xxiv] Ibid. Appleman. p.87

[xxv] Ibid. Yahara. p.31 All sources note that the 24th was a “well trained” division.

[xxvi] Ibid. Costello. p.555

[xxvii] Ibid. Yahara. p.15

[xxviii] Ibid. Yahara. pp. 14-15

[xxix] Ibid. Yahara. p.15

[xxx] Ibid. Yahara. pp. 20-22 and 32. Yahara details the initial plan and the changes necessitated by the departure of 9th Division. Rottman gives 9th Division a strength of 17,000. (Rottman p.46)

[xxxi] Ibid. Yahara. p.20

[xxxii] Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan. The Free Press and Division of MacMillan, Inc. New York, NY 1985. p.533

[xxxiii] Ibid. Rottman. p.25

[xxxiv] Ibid. Leckie p.32 and Costello. p.555. The unit was between 3000 and 3500 strong. Leckie simply identifies the force as the 2nd Infantry Unit while Costello identifies them as a Special Naval Landing Force. Appleman identifies Colonel Udo and the approximate number of troops but does not identify the unit. There appears to be confusion about the Japanese units, Appleman says that the 2nd Infantry Unit was constituted from survivors of 44th Mixed Brigade (which had lost most of its troops when their ship was sunk by an American submarine) and 15th Independent Mixed Regiment which was brought in to bolster it, but Yahara consistently places the reconstituted 44th in the south as part of the main defense. (see Appleman p.87) I will relay on Yahara as he was the 32nd Army Operations Officer and in a position to have first hand knowledge.

[xxxv] Ibid. Yahara. pp.22-23

[xxxvi] Ibid. Leckie. p.32

[xxxvii] Ibid. Leckie. pp.32-33

[xxxviii] Ibid. Toland. p.684

[xxxix] Ibid. Yahara. p.32

[xl] Ibid. Yahara. p.25

[xli] Ibid. Leckie. p.35

[xlii] Ibid. Leckie. p.19

[xliii] Ibid. Appleman. pp.52-58

[xliv] Ibid. Appleman. p.60

[xlv] Potter, E.B. Nimitz. Naval Institute Press. Annapolis, MD. 1976. p.369

[xlvi] Ibid. Costello. p. 556 and Morison p.530.

[xlvii] Ibid. Appleman. p.64. Leckie (pp. 67-68) names only 9 battleships: Arkansas, New York, Texas, Nevada, Idaho, New Mexico, Colorado, Tennessee and West Virginia. Of these ships all were built before the war and four were in commission before the US entered the First World War. Three had been at Pearl Harbor and with the exception of their engines the Tennessee and West Virginia had been completely rebuilt and modernized to the standards of the fast new battleships of the South Dakota class.

[xlviii] Ibid. Appleman. p.64

[xlix] Ibid. Leckie. p.69.

[l] Ibid. Leckie. p.72

[li] Ibid. Appleman. p.74

[lii] Ibid. Leckie. p.73

[liii] Ibid. Appleman. p.75

[liv] Ibid. Appleman. p.74

[lv] Ibid. Leckie. p.72 A point to note is that the “Demonstration” is still one of the Amphibious Operations in the USMC Amphibious doctrine.

[lvi] Sledge, E.B. With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa. Presidio Press. Novato, CA. 1981. Oxford University Press Paperback, New York, NY 1990. pp. 187-188 William Manchester in Goodbye Darkness talks about the first few days as his 6th Marine Division moved up North. He talks of the minimal resistance and the beauty of the island. Manchester, William, Goodbye Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War Little Brown and Company, New York NY, 1979.pp.356-357

[lvii] Ibid. Potter. pp.370-371

[lviii] Ibid. Leckie. p.78

[lix] Ibid. Manchester. p.357. Manchester notes that the fight in the north was like “French and Indian Warfare.”

[lx] Ibid. Appleman. p.148

[lxi] Ibid. Leckie. p.83

[lxii] Ibid. Appleman. p.148

[lxiii] Ibid. Appleman. p.104

[lxiv] Ibid. Appleman. pp.107-110

[lxv] Ibid. Appleman. pp.112-113.

[lxvi] Ibid. Appleman. p.112.

[lxvii] Ibid Yahara. p.35

[lxviii] Ibid. Leckie. p.104

[lxix] Ibid. Spector. p.534

[lxx] Ibid. Murray and Millet. p.514

[lxxi] Ibid. Appleman. pp. 126-127

[lxxii] Ibid. Leckie. pp.104-105

[lxxiii] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.514

[lxxiv] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.514

[lxxv] Ibid. Yahara. p.36

[lxxvi] Ibid. Leckie. p.108

[lxxvii] Ibid. Leckie. p.108

[lxxviii] Ibid. Yahara. p.36 The battle for a counter-offensive began on 6 April but was rejected. (Appleman. p.130) Yahara actually went to the commanders of the 24th and 62nd divisions and persuaded them not to use 3 battalions each but only two. (Leckie. pp.107-108)

[lxxix] Ibid. Leckie. p.113

[lxxx] Ibid. Appleman. p.137

[lxxxi] Ibid. Leckie. p.113.

[lxxxii] Ibid. Appleman. p.182. Leckie gives the total of 258 killed and 879 wounded. (Leckie. p.125) and estimates that most might have been uniformed civilians. Appleman citing Army figures estimates about 1,500 civilians. Even adding the American MIA totals the differences between Appleman and Leckie’s count of US casualties is puzzling.

[lxxxiii] Ibid. Leckie. p.126

[lxxxiv] Ibid. Leckie. p.127

[lxxxv] Ibid. Appleman. p.185

[lxxxvi] Ibid. Leckie. p.127

[lxxxvii] Ibid. Morison. p.553

[lxxxviii] Ibid. Appleman. pp.184-185

[lxxxix] Ibid. Leckie. p.128

[xc] Ibid. Leckie. p.128

[xci] Ibid. Leckie. p.131 It is interesting to note the vulnerability of the Sherman tanks to the obsolescent 47mm anti-tank guns used by the Japanese. By this stage of the war comparable German and Russian tanks would not be stopped by such weapons, baring a luck shot.

[xcii] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.515

[xciii] Ibid. Toland. p.706

[xciv] Ibid. Toland. pp.708-709

[xcv] Ibid. Leckie. p.138

[xcvi] Ibid. Appleman. pp. 243 and 247

[xcvii] Ibid. Leckie. p.139

[xcviii] Ibid. Toland. p.709

[xcix] McMillan, George. The Old Breed: A History of the First Marine Division in World War Two. The Infantry Journal Inc., Washington DC. 1949. p.375

[c] Ibid. Leckie. pp.148-149

[ci] Ibid. McMillan. p.377

[cii] Ibid. Yahara. p.37

[ciii] Ibid. Toland. p.710

[civ] Ibid. Toland. p.710

[cv] Ibid. Appleman. p.299

[cvi] Ibid. Appleman. p.302

[cvii] Ibid. Appleman. p.302. Rottman states 7,000 and Leckie 6,000.

[cviii] Ibid. Yahara. p.41

[cix] Ibid. Toland. p.712

[cx] Ibid. Yahara. p.42

[cxi] Ibid. Manchester. pp. 358-359. Manchester notes the distain that the Marines felt toward 27th Division which both they and 1st Marine Division had relieved in the south. Manchester comments that they felt that “the dogfaces lacked our spirit.”

[cxii] Ibid. Rottman. p.80

[cxiii] See Manchester pp.363-378 for a chilling description of the battle for Sugar Loaf.

[cxiv] Ibid. Leckie. pp.172-173

[cxv] Ibid. Appleman. pp.355-356

[cxvi] Ibid. McMillan. pp.385-395. 7th Marine Regiment suffered 1,249 casualties in this fight.

[cxvii] Ibid. Sledge. p.243

[cxviii] Ibid. Yahara. pp.67-73. Yahara has an interesting account both listing the military options available and the interaction between him and the other officers leading tom the withdraw. Among those he had to persuade were the divisional commanders of 24th and 62nd Divisions.

[cxix] Ibid. McMillan. p.401

[cxx] Ibid. McMillan. p.401

[cxxi] Ibid. Leckie. p.186

[cxxii] Ibid. Rottman. p.81

[cxxiii] Ibid. Rottman. p. 82 This included an amphibious landing by two regiments to flank the position which was the last opposed amphibious landing in the war.

[cxxiv] Ibid. Leckie. pp.199-200

[cxxv] Ibid. Rottman. p.83

[cxxvi] Ibid. Leckie. p.197 Leckie notes that the 2nd Marine Division had been transported back to Saipan rather than remain at sea as a target for Kamikazes. As a result the Marines had no reserve on the island.

[cxxvii] Ibid. Sledge. p.301

[cxxviii] Ibid. Toland p.721

[cxxix] Ibid. Appleman. p.456

[cxxx] Ibid. Yahara. p.133

[cxxxi] Ibid. Rottman. p.83

[cxxxii] Ibid. Yahara. p.144

[cxxxiii] Ibid. Yahara. pp.154-156. Yahara would hide among refugees hoping that he might escape to Japan but was discovered by an interrogation panel and identified on 26 July. (Yahara pp.189-191)

[cxxxiv] Ibid. Appleman. p. 473 This includes Navy losses of 4,907 killed and 4,824 wounded, mostly to Kamikaze strikes on ships supporting the operation. 10th Army lost 7,613 killed and 31,800 wounded. (Morison. p.556)

[cxxxv] Ibid. Appleman. pp473-474. Other sources report Japanese losses at 65,000 to 70,000. This may be from listing military civilians like those in the Naval Force and Okinawan militia as civilian casualties and only counting actually Japanese Army and Navy troops in this tally. Costello gives a count of 10,755 prisoners; this could again be a tally including these civilians and auxiliaries. (Costello. p.578) Rottman spends some time analyzing the discrepancies in the Japanese casualty numbers and comes to the same conclusion. (Rottman pp.84-85)

[cxxxvi] Ibid. Toland. p.726

[cxxxvii] Ibid. Rottman. p.85

[cxxxviii] Ibid. Yahara. p.31

[cxxxix] Ibid. Yahara. p.196.

[cxl] Ibid. Yahara. p.214

[cxli] Ibid. Rottman. p.73

[cxlii] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.514

[cxliii] Ibid. Leckie. p.162

[cxliv] Ibid. Spector. p.535

[cxlv] Ibid. Murray and Millett. p.515

[cxlvi] Ibid. Potter. p.373

[cxlvii] Ibid. Leckie. p.162 Leckie does not know if this was considered by Buckner though the tactic was used throughout the “island hopping” campaign where Japanese strong points were bypassed and isolated to whither on the vine.

[cxlviii] Ibid. Leckie. p.162

Bibliography

Appleman, Roy, E., Burns, James M., Gugeler, Russell A., and Stevens, John. The United States Army in World War II, The War In the Pacific. Okinawa: The Last Battle, Center of Military History, United States Army. Washington DC. 1948

Costello, John. The Pacific War: 1941-1945 Quill Publishers, New York, NY 1981

Leckie, Robert. Okinawa: the Last Battle in the Pacific Penguin Books, New York NY 1996.

McMillan, George. The Old Breed: A History of the First Marine Division in World War Two. The Infantry Journal Inc., Washington DC. 1949.

Manchester, William, Goodbye Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War Little Brown and Company, New York NY, 1979

Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War. An Atlantic Monthly Press Book, Boston MA 1963

Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War. The Belknap Press of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. 2000.

Potter, E.B. Nimitz. Naval Institute Press. Annapolis, MD. 1976.

Rottman, Gordon R. Okinawa 1945: The Last Battle. Osprey Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2002.

Sledge, E.B. With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa. Presidio Press. Novato, CA. 1981. Oxford University Press Paperback, New York, NY 1990.

Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan. The Free Press and Division of MacMillan, Inc. New York, NY 1985.

Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945. Random House, New York, NY 1970.

Willmont, H.P. The Second World War in the Far East. John Keegan General Editor. Cassell Books, London, 1999.

Yahara, Hiromichi. The Battle for Okinawa. Introduction and Forward by Frank Gibney. Translated by Frank Pineau and Masatoshi Uehara. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY. 1995.

USS Raleigh CL-7 fighting to stay afloat

USS Raleigh CL-7 fighting to stay afloat USS Detroit CL-8 1945, final configuration

USS Detroit CL-8 1945, final configuration USS Utah Memorial (Google Earth)

USS Utah Memorial (Google Earth)

![clausewitz[1]](https://padresteve.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/clausewitz1.jpg?w=500)

![1942x~This_is_the_Enemy_US_[2]](https://padresteve.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/1942xthis_is_the_enemy_us_2.jpg?w=500)