Custer leads his Michigan Cavalry Brigade on July 3rd

On the evening of July 2nd 1863 with the attacks of Longstreet now finished and Ewell’s abortive battle for Culp’s Hill reaching its bloody climax, Major General J.E.B. Stuart finally arrived at Robert E Lee’s headquarters on Seminary Ridge. Stuart and his troopers had been missing from Lee’s army since the evening of June 23rd, causing Lee no end of anxiety as well as depriving Lee of his most trusted source of information regarding enemy movements and intentions.

Stuart’s tired and hungry brigades were at Carlisle where he was endeavoring to take that town from local militia when Stuart leaned the location of Lee’s army. He was directed to “move to Gettysburg. Jeb did not delay compliance. Exhausted troopers mounted their staggering horses,” [1] and began the ride to Gettysburg where much of the army greeted with “joyful shouts” [2] which was a relief to his exhausted troopers. Stuart’s chief of staff Major Henry McClellan wrote: “For eight days and nights the troops had been marching incessantly. On the ninth night they rested within the shelter of the army, and with a grateful sense of relief which words cannot express.” [3]

Stuart rode ahead to Lee’s headquarters where unlike the “joyful” greeting his troops were accorded, he was met with a frosty reception by his beloved commander. Over the eight days of his absence Lee Apparently the meeting between Lee and his Cavalry division commander was short “abrupt and frosty. As soldier-historian Porter Alexander put it, “although Lee said only, ‘Well, General, you are here at last,’ his manner implied rebuke, and it was understood by Stuart.” [4] One account noted that “Lee reddened at the sight of Stuart and raised his arm as if he would strike him.” [5] Lee’s cold greeting stunned Stuart, who “may have been disappointed that no applause greeted his return from his longest raid, which he was to persuade himself was his greatest.” [6] Henry McClellan reported that Stuart “regarded the incident as painful beyond description.” [7]

In his official report of the battle “Lee would allude to Stuart with but a single pejorative sentence: “The movements of the Army preceding the Battle of Gettysburg had been much embarrassed by the absence of the cavalry.” [8]

Stuart left as quickly as he arrived and in his official report he noted that his new orders were to take up a position “on the left wing of the Army of Northern Virginia.” [9] For a man like Stuart whose soldierly skills as a cavalry commander and leader were only matched by his vanity the incident was humiliating, he had failed Robert E Lee.

Stuart devised a plan to put his strong>“entire cavalry force in a position from which he could separate the Union cavalry from the main body of the army and at proper moment swoop down on its rear.” [10] However, there is no supporting evidence to indicate that Lee ever ordered Stuart to conduct an attack, and the suggestion runs counter to how Lee employed his cavalry throughout the war. The idea that Lee intended Stuart “to commit his small cavalry force to an attack on infantry belies every tactical lesson the Civil War afforded.” [11] It was a bad plan and it was now beyond the capabilities of Stuart’s troopers exhausted troopers and their broken mounts, who would face similar numbers of relatively fresh Federal cavalry; which as noted before was now their equal in leadership, training, organization and equipment.

Stuart moved four of his brigades the following morning to the north and east. He hoped to cover his movement from Federal observation but he was discovered by “watchful Union signal officers” who reported “large columns of cavalry moving toward the right of the Union line” [12] The message was relayed by Howard to Brigadier General David Gregg of the Second Cavalry Division who quickly deployed his troopers to meet the emerging threat. Stuart unjustly blamed the discovery of his force on brigades of Hampton and Fitzhugh Lee who he said had “debouched onto open ground and disclosed his presence.” But Stuart himself was also to blame for the discovery as he announced his force’s presence by bringing one cannon from Griffin’s battery of his artillery “to the edge of the woods and fired a number of random shots in different directions, himself giving orders to the gun.” [13] For a veteran officer such as Stuart that decision is inexplicable.

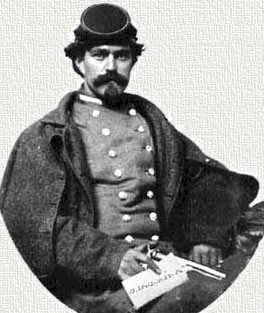

Brigadier General David Gregg

When Gregg received word of Stuart’s approach from Alfred Pleasanton, he was ordered to intercept him and in the process relieve the Michigan Brigade of the newly minted Brigadier General George Custer, which was deployed there so it could rejoin Judson Kilpatrick’s Third Cavalry Division on the extreme Federal left.

However, upon his arrival Gregg realized that he would be outnumbered and that Stuart posed “a serious threat to the Union rear.” [14] Custer indicated that he thought Gregg would soon have a battle and Gregg replied “in that case he would like to have the assistance of his Michigan brigade.” Custer agreed with Gregg and said that he would be “only too happy” to stay.” [15] Without bothering to consult his Cavalry Corps Commander, Major General Pleasanton, Gregg ordered Custer to remain with him and “willingly risked his military career and reputation in his anxiety to protect the Federal rear.” [16]

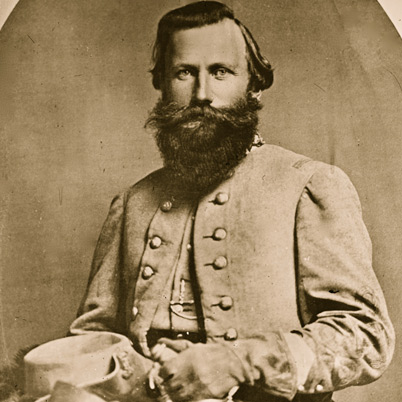

Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer

Gregg’s action was yet another of the superior judgments executed by a Federal commander during the battle. It was an outstanding example of how Federal commanders on the whole recognized the overall tactical situation and used their judgment to take action when waiting for a superior could prove fatal to the army. In our modern understanding it would be an example of how Mission Command is to work.

The main battle took place after Three P.M. when Pickett and Pettigrew’s divisions were battling for their lives in their ill-fated assault on Cemetery Hill. “For almost an hour, from 12:300 to 1:30, both sides jockeyed for advantage in a long range duel of cavalry, fighting with carbines and artillery.” [17] were a number of charges and counter charges, culminating in a “furious saber-swinging mounted counterattack by Custer and his Michigan cavalry, Custer at their head crying, “Come on, you Wolverines!” [18] As the clash continued “Stuart saw that General Gregg did not intend to allow an assault on Meade’s rear. The enemy was as stoutly determined as they had been at Brandy Station or in the passes in Northern Virginia.” [19] The battle evolved into a “smaller-scale version of the cavalry scrum at Brandy Station a month before.” [20]

Though the battle was tactically a draw, Gregg and Custer’s troopers had prevailed, casualties on both sides were well under ten percent, 254 Union and 181 Confederate. But it was a victory for Gregg who had forced Stuart to enter a battle “in which the Confederates gained nothing except the “glory of fighting” [21] and had stopped Stuart from his objective of disrupting the Federal rear and aiding Pickett’s assault. Stuart wrote: “Had the enemy’s main body been dislodged, as was confidently hoped and expected, I was in precisely the right position….” [22]

As the battle to the east of town wound down Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick ordered a “poorly calculated mounted attack on some of John Bell Hood’s men down by Big Round Top.” [23] Kilpatrick ordered Brigadier General Elon Farnsworth to attack the dug in Confederates. Farnsworth was incredulous and objected saying “No successful charge can be made against the enemy in my front.” [24] When Kilpatrick questioned his courage Farnsworth said “if you order the charge I will lead it, but you must take the responsibility.” [25] Farnsworth told one of his officers “My God Hammond, Kil is going to have a cavalry charge. It is too awful to think of….” [26] Farnsworth’s troopers struck Law’s brigade and the Alabama troops of Colonel William Oates who had been repulsed the day before at Little Round Top. Defending rugged ground and backed by artillery it was Oates’ soldiers turn to enact slaughter on the charging Federals.

Elon Farnsworth

It was a hopeless charge. Farnsworth’s units were surrounded and while many men were able to ride to safety Farnsworth and ten or so of his men were cut off,

and he was wounded at least three times and knocked from his horse. Offered the opportunity to surrender by a Confederate officer he refused and “with an oath he swore he would not do it, and placing his pistol to his own body shot himself through the heart.” [27] Though the assault was going nowhere the now frantic Kilpatrick hurled the last regiment available into the fight screaming at its commander “Why in hell and damnation don’t you move those troops out,” The troopers of the 18th Pennsylvania “went forward and were stopped in their tracks.” [28]

During the battle with Gregg and Custer’s troopers, Stuart displayed little of his normally sharp tactical leadership and took little part in the battle leaving the conduct of it to his subordinates. Though the Federal Horse Artillery was outnumbered Gregg used the two batteries he had far more effectively than Stuart used his. Additionally Gregg had two brigade commanders willing to take the fight to the Confederates, something that had not been common before the Gettysburg campaign. Stuart again claimed victory as he had at Brandy Station, but once more his words were deceptively inaccurate, he had been bested by the Federals once again.

Stuart’s aid Major Henry McClellan wrote of the battle on the Cavalry Field:

“The result of this battle shows that there is no possibility that Stuart could successfully have carried out his intention of attacking the rear of the Federal right flank, for it was sufficiently protected by Gregg’s command. As soon as General Gregg was aware of Stuart’s presence he wisely assumed the aggressive and forced upon Stuart a battle…while Gregg himself performed the paramount flank of protecting the right flank of the Federal Army.” [29]

McClellan’s analysis is both succinct and accurate. As Stuart’s forces retired and Pickett’s shattered command withdrew the Battle of Gettysburg was effectively over.

Peace

Padre Steve+

Notes

[1] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.586

[2] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.362

[3] McClellan, Henry Brainerd The Life and Campaigns of Major General J.E.B. Stuart Commander of the Cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia 1885. Digital edition copyright 2011 Strait Gate Publications, Charlotte NC location 6373 of 12283

[4] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg A Mariner Book, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 2003. pp.257-258

[5] Davis, Burke J.E.B. Stuart: The Last Cavalier Random House, New York 1957 p.334

[6] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.586

[7] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.258

[8] Taylor, John M. Duty Faithfully Performed: Robert E Lee and his Critics Brassey’s Dulles VA 1999 p.150

[9] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Books New York 2001 p.316

[10] Coddington, Edwin B. Gettysburg: A Study in Command. A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York 1968 p.520

[11] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg the Last Invasion p.429

[12] Ibid. Coddington pp.520-521

[13] Ibid. McClellan The Life and Campaigns of Major General J.E.B. Stuart location 6486 of 12283

[14] Ibid. Coddington p. 521

[15] Ibid. Coddington p. 521

[16] Ibid. Coddington p. 521

[17] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg the Last Invasion p.430

[18] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg the Last Invasion p.430

[19] Ibid. Davis. J.E.B. Stuart p.338

[20] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg the Last Invasion p.430

[21] Ibid. Coddington p. 523

[22] Wert, Jeffry D. A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2011 p.271

[23] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg the Last Invasion p.430

[24] Wert, Jeffery D. Gettysburg Day Three A Touchstone Book, New York 2001 p.277

[25] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.277

[26] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.463

[27] Oates, Willam C. and Haskell, Frank A. Gettysburg: The Confederate and Union Views of the Most Decisive Battle of the War in One Volume Bantam Books edition, New York 1992, originally published in 1905 p.122

[28] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.463

[29] Ibid. McClellan The Life and Campaigns of Major General J.E.B. Stuart location 6516 of 12283