Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

Today, since I am tired and it looks like I am not get a chance to write anything new before we begin our trip to Germany I am going to I am post a revised part of one of my Civil War texts. This one deals with the organization, use, and development of cavalry during the war in the United States Army and the Army of the Confederate States Army.

Peace

Padre Steve+

Cavalry in the United States in the ante-bellum period and during the war differed from the massive cavalry arms of European armies. In Europe the major armies had two types of cavalry units, light cavalry which was used for scouting, reconnaissance and screening, and heavy cavalry which was designed to be employed at the decisive moment of the battle in order to break enemy infantry formations through the shock of the massed charge. Napoleon always had a number of reserve cavalry corps to fulfill this mission.

The United States had little in the way of a cavalry tradition. Cavalry was considered by many American political leaders to be too aristocratic for America and as a result this arm of service suffered. In its early years the U.S. Army did not have any sizable mounted formations to call upon.

There were a number of other reasons for the cultural and institutional resistance to a strong were trained and armed cavalry service in the United States Army.

First, the nation as a whole distrusted large standing armies and viewed them as a source of potential tyranny and traditional cavalry was the most aristocratic part of European armies. The struggle between Federalists who desired a standing army and a militia that could be organized under central control and Republicans who wanted nothing of the sort was a constant source of friction in the new republic. Anti-Federalists saw standing armies as despotic, as one anti-federalist publication noted “In despotic governments, as well as in all the monarchies of Europe, standing armies are kept to execute the commands of the prince or magistrate…. By establishing an armed force to execute the laws at the point of the bayonet – a government of all others is the most to be dreaded.” [1]

As such, much of the nation’s military spending was focused on the Navy, which was deemed as less of a domestic threat, and even then the limited budgets meant that many times significant numbers of ships were laid up in ordinary. The Regular Army struggled to maintain its existence from 1787 until the War of 1812 in the face of Republican opposition led by Thomas Jefferson. After the War of 1812 the nation soon lost interest in paying for a standing army and in 1821 against the wishes of Secretary of War John C. Calhoun slashed “the Army’s strength by eliminating regiments and reducing the number of officers.” [2] With appropriations cut to the bone there was no effort to create a cavalry arm for the service as cavalry formations were much more expensive to equip and maintain than infantry.

Even though the Regular Army survived, it was tiny in. Its strength ranged from 3,000 to 6,000 men, the bulk were infantry who for the most part formed a frontier constabulary or manned coastal fortifications. However, in 1796 two companies of Dragoons were authorized, but even so the mounted arm remained a poor stepchild. Likewise, “Doctrinal resistance to battle cavalry was also very strong. The ‘American’ tradition had no place for such an animal….” [3]

Finally as the nation expanded westward the army formed the First Dragoon Regiment in 1833. In 1836 the Second Dragoons were organized. The Dragoons were basically mounted infantry formations and these units were scattered about the expanding western frontiers of the nation were employed “guarding the routes of expansion as far west as the Rocky Mountains and as far south as the Red River.” The army also formed Mounted Infantry units, which like the Dragoons were hybrid formations. Though many thought that such units promised “a double return on the government’s investment, but which did not manage to provide either an efficient force of infantry or an efficient battle force of cavalry.” [4]

The First Dragoons would serve with “distinction in numerous engagements in what was to become California and New Mexico.”[5] The regiment fought well in the War with Mexico but suffered heavy casualties in the process. When the war ended it was again dispersed on the frontier when it was used to protect settlers and fight Native American tribes that resisted the advance of the flood of white settlers.

One of the reasons for the heavy losses sustained by the First Dragoons in Mexico was because “West Point cavalry doctrine was based upon a Napoleonic mania for the massed saber charge.” [6] However, one problem with this was that the United States Army never had sufficient numbers of cavalry, not to mention a death of heavy cavalry needed to make such attacks successful, but in Mexico the limited number of cavalry troops available made such tactics untenable. The tactic had often worked well for Napoleon and massed cavalry charges were used to sweep the field of broken enemy infantry formation. However, the suicidal charge of Marshal Ney’s vaunted Cuirassiers against the Duke of Wellington’s highly disciplined infantry squares at Waterloo had shown that such tactics were destined for extinction unless they were part of an all arms assault. Marshal Ney failed because he used his cavalry in unsupported attacks against the allied infantry squares rather advancing artillery to support the attack or bringing infantry up to force the defenders out of their squares.

It was not until the 1850s that the army organized its first two Cavalry regiments for duty on the frontier. The new cavalry regiments were the equivalent of European light cavalry and during the war primarily served in that role, conducting reconnaissance, raids, and screening the army. Even so the tactical doctrine taught at West Point focused continued to “support the continuing predominance of the offense over the defense, of shock over firepower” [7] which was at odds with the cavalry’s actual capabilities.

Cavalry regiments were usually composed of four to six squadrons, each squadron having two companies. Cavalry regiments could range in size from 660 to nearly 1,200 troopers. Both the Union and the Confederacy grouped their cavalry into brigades and later divisions, but the Confederates were first to establish cavalry brigades and divisions. By 1863 both the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac each formed cavalry corps. Cavalry tactics “complemented conventional infantry assault tactics, emphasizing shock and the role of the saber”; unfortunately both the infantry and the cavalry developed their doctrine independently. U.S. Army Cavalry doctrine was prescribed in Philip St. George Cooke’s Cavalry Tactics which was published in 1861 while a corresponding Confederate manual, Joseph Wheeler’s A Revised System of Cavalry Tactics appeared in 1863.

Before the war American cavalry units tended to operate in small numbers with regiments seldom sending into action more than a few companies at once. At the beginning of the war the Federal government decided to form just five mounted regiments, including two of Dragoons and one of Mounted Infantry. It soon decided to add a sixth but the units were hindered by the fact that many of their officers had gone to the Confederacy, and some of those remaining “would jump to volunteer units to secure higher rank, pay, and prestige.”[8] The result was defeat after defeat at the hands of J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry.

Eventually large scale programs to train and equip large numbers of volunteers and the Regulars combined with wartime reorganizations and solid leadership would make the Federal cavalry a force that was able to hold its own and then to sweep Confederate cavalry from the field. But it took time to train cavalry, and early Union commanders like McClellan refused to take that time and a “whole year was lost as a result, during which the cavalry was allowed to indoctrinate itself in the notion that it could never make use of European standards.” [9] While McClellan may have done well in organizing and training the infantry and artillery of the Army of the Potomac, he did little in the way of providing the mounted arm with leaders, training or missions that would increase their effectiveness. Unlike Stuart who combined his troopers with effective horse artillery, McClellan “failed to appreciate the advantage of coordinating the tactical strengths of cavalry with those of infantry and artillery.” [10]

J.E.B. Stuart

While the South did struggle at times with its cavalry arm but did have an advantage in that the vast majority of their cavalry troopers owned their mounts and were experienced horsemen, something that could not be said of the many city dwellers who volunteered for duty in the Union cavalry. But the initial Southern superiority in cavalry was also due to the fact that “the principal of massing regiments into brigades and divisions was pursued earlier than by the Federal.” [11] In contrast McClellan “followed the evil course of reducing mounted regiments to their smallest components for operational use.” Likewise, he “wasted cavalry’s potential and depressed its morale by employing it as couriers, bodyguards for his subordinates, pickets for his encampments, and wagon train escorts, instead of as combat troops.” [12] The result as one would expect was that for the first two years of the war “J.E.B. Stuart and his horsemen were able, literally, to run rings around their opponents.” [13]

One Union writer compared the development of the Confederate and Union cavalry arms during the war:

“The habits of the Southern people facilitated the formation of cavalry corps which were comparatively efficient even without instruction; and accordingly we see Stuart, John Morgan, and Forrest riding around with impunity around the Union armies, and destroying or harassing their communications. Late in the war that agency was reversed. The South was exhausted of horses, while the Northern cavalry increased in numbers and efficiency, and acquired the audacity which had characterized the Southern.” [14]

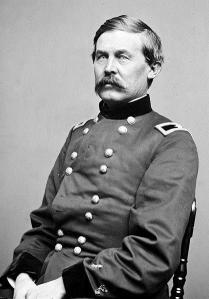

John Buford

As such much of the initial improvement in the Union cavalry arm were due to solid commanders like Brigadier General John Buford to teach new recruits as well as discouraged veterans to become effective cavalrymen.

Cavalry remained a fairly small in comparison to the infantry and artillery branches of service. Even during the wartime expansion the amount of cavalry available was miniscule compared to European armies. On the average only about 8% of the Army of the Potomac was composed of cavalry, compared to Napoleon’s 20 to 25%. [15] Part of this was due to the perceived cost of the cavalry arm which many believed was too expensive to maintain on a large scale: “estimates held that every twelve companies mounted and outfitted at public expense would rob the Treasury of over $300,000 a year merely to cover upkeep on animals, remounts, weapons, and equipment….” [16]

The cost of equipping cavalry was high enough that in the South that troopers had to procure their own mounts. Edwin Coddington noted that the Confederate policy “was a wonderful arrangement for keeping the strength of the cavalry below par, much more than enemy bullets, for it encouraged absenteeism.” [17] The Confederate government paid the own for the use of the horse, and a cash reimbursement if it was lost in combat, but if it was lost in any other manner the soldier had to get another horse if he wanted to remain in the service. Since the Confederates never set up a “centralized replacement service” troopers who lost their mount “had to go home to procure a new horse. If he were a Virginian he needed from thirty to sixty days to accomplish his purpose, and a much longer time should he have to come deeper south.” [18]

Despite the doctrinal predilection to the offense and using the cavalry as a shock unit, the U.S. Army formed no heavy cavalry formations on the order of the famous French Cuirassiers, named after their armored breastplates and metal helmets which were the primary type of cavalry used in Europe for such tactics. As such, during the Civil War both Union and Confederate cavalry formations were primarily assigned to reconnaissance and screening missions normally conducted by light cavalry units in Europe. These larger formations began to be used en masse for the purpose of raiding by both sides “but in the hands of J.E.B Stuart and his friends it became little more than a license to roam off into the enemy’s rear areas looking for plunder and glory.”[19] The cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac was used in a similar manner to raid enemy rear areas with often dreadful results which contributed nothing to the overall goal of defeating Lee’s army. A prime example was when Joseph Hooker detached his newly formed Cavalry Corps under George Stoneman to raid Richmond leaving the flank of the army uncovered at Chancellorsville.

Quite often the soldiers assigned to the infantry and artillery had little use for the cavalry who they saw as pampered and contributing little to the war. Many infantrymen held the “cavalry in open contempt. “These cavalry are a positive nuisance,” an officer in the 123rd Illinois wrote. “They won’t fight, and whenever they are around they are always in the way of those who will fight.” [20] Disdainful Confederate infantrymen “greeted their cavaliers with “Here’s your mule!” and “their Federal counterparts would exclaim: “There’d going to be a fight, boy; the cavalry’s running back!” and “Whoever saw a dead cavalryman.”[21]

The lethality of the rifled musket also made the classic Napoleonic cavalry charge against enemy infantry a costly and dangerous enterprise if the enemy infantry still had the means to make organized resistance, and if the cavalry assault was not supported by infantry and cavalry.. An example of this was the ill-fated cavalry attack ordered by Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick against the men of Lafayette McLaws’s well prepared division on the Confederate right after the failure of Pickett’s Change at Gettysburg.

Cavalry tactics began to change during the war. Both sides used their cavalry for raids, sometimes very large ones, and operations against enemy partisans in their rear areas. In each case the cavalry was typically deployed by itself and even when it accompanied the armies into battle cavalry units were typically employed on the periphery of the battle. As such as Griffith wrote, “Civil War doctrine of raiding… was not only a deliberate turn away from the hope of victory on the battlefield, but it actually removed the means by which victory might have been won at the very moment when those means were at last starting to be properly efficient.” [22] The lack of heavy cavalry of the European model sometimes kept commanders from completing victories, one can only imagine what would have happened had George Meade had a division of heavy cavalry at hand to sweep the Confederates from the battlefield after Pickett’s Charge.

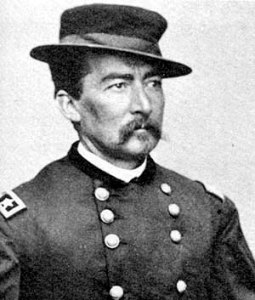

Philip Sheridan

Tactics only began to change when General Philip Sheridan took command of Grant’s cavalry. Sheridan kept the cavalry close to the main body of the arm. Sheridan had replaced Major General Alfred Pleasanton as commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac in early 1864. It is quite possible had he not died in December 1863 that the post would have gone to John Buford, but Sheridan had a vision for the cavalry that foreshadowed modern operational art. Sheridan wanted to organize the Cavalry Corps by concentrating it “into a powerful striking arm. He desired to do this, first, to deal with the Confederate cavalry, on the theory that “with a mass of ten thousand mounted men… I could make it so lively for the enemy’s cavalry that… the flanks and rear of the Army of the Potomac would require little or no defense.” [23] Sheridan was making no idle boast as by now his troops “were not only more numerous, but they had better leaders, tactics, and equipment than before,” [24] especially when it came to the Spencer repeating rifle which was now standard issue for the cavalrymen, and which gave them a tremendous advantage in firepower over Stuart’s now ill-equipped troops.

Sheridan first did this at the beginning of the Wilderness campaign when he took his 10,000 strong corps around the Confederate flank. Sheridan had been quarreling with Meade about the latter’s insistence that Sheridan’s horsemen were clogging the roads that his infantry needed to advance upon. In the heated discussion Sheridan came very close to being insubordinate with Meade. Meade reportedly told Sheridan that “Stuart “will do about how he pleases anyhow” to which Sheridan supposedly replied “Damn Stuart, I can trash hell out of him any day.” [25] Furious, Meade went and reported the matter to Grant. Grant listened and replied “Did Sheridan say that?… He usually knows what he is talking about. Let him go ahead and do it.” [26] At Grant’s request Meade provided Sheridan with new orders to concentrate his cavalry, march south and engage Stuart’s cavalry. Unlike previous raids which sought to avoid battle with Stuart’s troops in order to hit prescribed objectives, above all Sheridan wanted to engage and defeat the legendary Confederate cavalier. He “defined the raid as “a challenge to Stuart for a cavalry duel behind Lee’s lines in his own country.” And the more there were of the gray riders when the showdown was at hand, the better he would like it, since that would mean there were more to be smashed up.” [27]

Sheridan’s column totaled nearly 13,000 men and was nearly 13 miles long as he proceeded at a slow pace around Lee’s army and south towards Richmond. In addition to his horsemen he brought all of his horse artillery batteries. He was well around Lee’s flank before he was discovered and during the march his troops burned a depot and over one hundred railroad cars containing “close to a million rations of meat and better than a half million of bread, along with Lee’s entire reserve of medical stores.” [28]

On May 11th Stuart managed to intercept Sheridan’s column at a place called Yellow Tavern, just south of Ashland and the Ana River, but his corps was outnumbered by at least three to one. Three well trained, experienced, equipped, and superbly led Federal cavalry divisions confronted Stuart. With no hopes of fighting an offensive action, Stuart’s troops fought dismounted and were routed by the superior Bluecoats who continued on to cut the railroad between Lee’s army and Richmond. During the battle Stuart, who had cheated death on a number of occasions was mortally wounded. The Confederate cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia would never recover, and to Southerners Stuart’s death was a profound psychological blow, only slightly worse than that of Stonewall Jackson a year before. Robert E. Lee, to who Stuart was like a son took the loss harder than he had taken Jackson’s. “I can scarcely think of him without weeping,” he told one of Stuart’s officers.” [29]

As the armies in the East and West dueled throughout 1864, Sheridan and other Federal cavalry officers transformed the Union cavalry into a striking force which could be the spearhead of the army and use new tactics to overcome the problem of combining fire with rapid maneuver which had never been satisfactory applied by the infantry. There were four components in the new tactical mix: “fast operational mobility on horseback out of contact with the enemy; a willingness to take cover and fight on foot when the enemy was close; new repeating carbines to give enhanced firepower; and a mounted reserve to make the sabre charge when the moment was ripe.” [30] Sheridan would apply these tactics in his later campaigns against Jubal Early in the Shenandoah Valley and during the Appomattox campaign and his cavalry, working with infantry and artillery smashed the beleaguered Confederate armies which tried to oppose them. The reorganized cavalry was not the answer to all of the battlefield problems faced by Civil War commanders but it gave Union commanders an impressive weapon in which the speed and firepower of the cavalry could be readily combined with artillery and infantry to achieve decisive results. On the Confederate side, General Joseph Wheeler who commanded the cavalry in the west, Wheeler usually fought dismounted in “skirmish order using field fortification, whether skirmishing independently or in the line…. In the last major action of the war, he dramatically displayed how cavalry had become tactically integrated with infantry. At Bentonville, while fighting his cavalry dismounted, first on the right, then moving around to the left flank, Wheeler constructed a line of breastworks 1,200 yards long.” [31]

European cavalry officers found little to admire in American use of cavalry. Few paid attention to the importance of fighting dismounted and working as part of a combined arms team. In August 1914 their cavalry formations paid severe price for ignoring the realities of modern war, realities which the Americans, both Union and Confederate learned during the Civil War.

Notes

[1] ____________ Anti-Federalists Fear a Large Military “Brutus I.” “To the Citizens of the State of New York” 1787 in Major Problems in American Military History edited by John Whiteclay Chambers II and G. Kurt Piehler, Houghton-Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York 1999 p. 103

[2] Ibid. Millet and Maslowski For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States p.122

[3] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.181

[4] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.181

[5] Longacre, Edward G. John Buford: A Military Biography Da Capo Press, Perseus Book Group, Cambridge MA p.33

[6] Thomas, Emory M. Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart University of Oklahoma Press, Norman OK 1986 and 1999 p.30

[7] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.21

[8] Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations, during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June- 14 July 1863. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 1986 p.44

[9] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.182

[10] Ibid. Longacre The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations, during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June- 14 July 1863 p.45

[11] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.181

[12] Ibid. Longacre The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations, during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June- 14 July 1863 p.45

[13] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.183

[14] Buell, Don Carlos. East Tennessee and the Campaign of Perryville in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts. Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ p.51

[15] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.181

[16] Ibid. Longacre The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations, during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June- 14 July 1863 p.43

[17] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.17

[18] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command p.17

[19] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.183

[20] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.20

[21] Ibid. Longacre The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations, during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June- 14 July 1863 p.45

[22] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War pp.183-184

[23] Ibid. Weigley A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History 1861-1865 p.369

[24] Ibid. Whelan Bloody Spring: Forty Days that Sealed the Confederacy’s Fate p.181

[25] Ibid. Thomas Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart p.288

[26] Catton, Bruce Grant Takes Command Little, Brown, and Company, New York, Toronto, London 1968 and 1969 p.216

[27]Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Three Red River to Appomattox p.564 p.224

[28] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Three Red River to Appomattox p.564 p.225

[29] Ibid. Korda, Clouds of Glory p.626

[30] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.184

[31] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.298