Friends of Padre Steve’s World

Judy and I are now on our last full day in Germany and the Oktoberfest in Munich. Tomorrow evening we should be back in the good old USA. Since I am posting in advance as I do not plan on writing anything in Germany unless something really important happens, I am re-posting a modified version of an article that I first posted over a year ago.

For me it began in February 2008 when on the way back from Iraq the military charter aircraft bringing us home stopped in Ramstein Germany. After a few hour layover we re-boarded the aircraft but we were no longer alone, the rest of the aircraft had been filled with the families of soldiers and airmen stationed in Germany. Just days before most of us had been in Iraq or Afghanistan. The cries of children and the intrusion of these people, not bad people by any means on our return flight was shocking, it was like returning to a world that I no longer knew.

I think that coming home from war, especially for those damaged in some way, in mind, body or spirit is harder than being at war.

In that thought I am not alone. Erich Maria Remarque in his classic novel All Quiet on the Western Front wrote:

“I imagined leave would be different from this. Indeed, it was different a year ago. It is I of course that have changed in the interval. There lies a gulf between that time and today. At that time I still knew nothing about the war, we had been only in quiet sectors. But now I see that I have been crushed without knowing it. I find I do not belong here any more, it is a foreign world.”

Likewise, Guy Sajer a French-German from the Alsace and veteran of the Grossdeutschland Division on the Eastern Front in World War II noted at the end of his book The Forgotten Soldier:

“In the train, rolling through the sunny French countryside, my head knocked against the wooden back of the seat. Other people, who seemed to belong to a different world, were laughing. I couldn’t laugh and couldn’t forget.”

I have been reminded of this several times in the past week. It began walking through a crowded Navy commissary on Saturday, in the few minutes in the store my anxiety level went up significantly. On Tuesday I learned of the death of Captain Tom Sitsch my last Commodore at EOD Group Two, who died by his own hand. His life had come apart. After a number of deployments to Iraq as the Commander EOD Mobile Unit 3 and of Task Force Troy he was afflicted with PTSD. Between June of 2008 and the end of 2009 he went from commanding an EOD Group to being forced to retire. Today I had a long talk with a fairly young friend agonizing over continued medical treatments for terminal conditions he contracted in two tours in Iraq where he was awarded the Bronze Star twice.

I have a terrible insomnia, nightmares and night terrors due to PTSD. My memories of Iraq are still strong, and this week these conditions have been much worse. Sager wrote:

“Only happy people have nightmares, from overeating. For those who live a nightmare reality, sleep is a black hole, lost in time, like death.”

Nearly 20 years after returning from war, a survivor of the 1st Battalion 308th Infantry, the “Lost Battalion” of World War One, summed up the experience of so many men who come back from war:

“We just do not have the control we should have. I went through without a visible wound, but have spent many months in hospitals and dollars for medical treatment as a result of those terrible experiences.”

Two time Medal of Honor winner Major General Smedley Butler toured Veterans hospitals following his retirement from the Marine Corps. He observed the soldiers who had been locked away. In his book War is a Racket:

“But the soldier pays the biggest part of this bill. If you don’t believe this, visit the American cemeteries on the battlefields abroad. Or visit any of the veterans’ hospitals in the United States….I have visited eighteen government hospitals for veterans. In them are about 50,000 destroyed men- men who were the pick of the nation eighteen years ago. The very able chief surgeon at the government hospital in Milwaukee, where there are 3,800 of the living dead, told me that mortality among veterans is three times as great as among those who stayed home.”

Similarly Remarque wrote in All Quiet on the Western Front:

“A man cannot realize that above such shattered bodies there are still human faces in which life goes its daily round. And this is only one hospital, a single station; there are hundreds of thousands in Germany, hundreds of thousands in France, hundreds of thousands in Russia. How senseless is everything that can ever be written, done, or thought, when such things are possible. It must be all lies and of no account when the culture of a thousand years could not prevent this stream of blood being poured out, these torture chambers in their hundreds of thousands. A hospital alone shows what war is.”

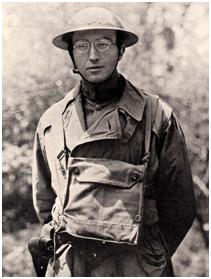

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Whittlesey

Sometimes even those who have been awarded our Nation’s highest award for valor succumb to the demons of war that they cannot shake, and never completely adjust to life at “home” which is no longer home. For them it is a different, a foreign world to use the words of Sager and Remarque. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Whittlesey won the Medal Medal of Honor as Commander of 1st Battalion 308th Infantry, the “Lost Battalion” in France. After the war he was different. He gave up his civilian law practice and served as head of the Red Cross in New York. In that role, and as the Colonel for his reserve unit, he spent his time visiting the wounded who were still suffering in hospitals. He also made the effort to attend the funerals of veterans who had died. The continued reminders of the war that he could not come home from left him a different man. He committed suicide on November 21st 1921not long after serving as a pallbearer for the Unknown Soldier when that man was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

In his eulogy, Judge Charles L. Hibbard noted:

“He is sitting on the piazza of a cottage by the sea on a glorious late September day but a few weeks ago. . . He is looking straight out to sea, with naught but sea between him and that land where lie so many of his boys. The beating surf is but an echo, the warm, bright sunshine, the blue sky, the dancing waves, all combine to charm. But a single look at his face and one knows he is unconscious of this glory of Nature. Somewhere far down in the depths of his being or in imagination far off across the waters he lives again the days that are past. That unconscious look has all the marks of deep sorrow, brooding tragedy, unbearable memories. Weeks pass. The mainspring of life is wound tighter and tighter and then comes the burial of the Unknown Soldier. This draws the last measure of reserve and with it the realization that life had little now to offer. This quiet, reserved personality drew away as it were from its habitation of flesh, thought out the future, measured the coming years and came to a mature decision. You say, ‘He had so much to live for – family, friends, and all that makes life sweet.’ No, my friends, life’s span for him was measured those days in that distant forest. He had plumbed the depth of tragic suffering; he had heard the world’s applause; he had seen and touched the great realities of life; and what remained was of little consequence. He craved rest, peace and sweet forgetfulness. He thought it out quietly, serenely, confidently, minutely. He came to a decision not lightly or unadvisedly, and in the end did what he thought was best, and in the comfort of that thought we too must rest. ‘Wounded in action,’ aye, sorely wounded in heart and soul and now most truly ‘missing in action.’”

Psychologist and professor Dr. Ari Solomon analyzed the case of Colonel Whittlesey and noted:

“If I could interview Whittlesey as a psychologist today, I’d especially have in mind … the sharp discrepancy between the public role he was playing and his hidden agony, his constant re-exposure to reminders of the battle, his possible lack of intimate relations, and his felt need to hide his pain even from family and dearest friends.”

I wish I had the answer. I have some ideas that date back to antiquity in the ways that tribes, clans and city states brought their warriors home. The warriors were recognized, there were public rituals, sometimes religious but other times not. But the difference is that the warriors were welcomed home by a community and re-integrated into it. They were allowed to share their stories, many of which were preserved through oral traditions so long that they eventually were written down, even in a mythologized state.

But we do not do that. Our society is disconnected, distant and often cold. Likewise it is polarized in ways that it has not been since the years before our terrible Civil War. Our warriors return from war, often alone, coming home to families, friends and communities that they no longer know. They are misunderstood because the population at large does not share their experience. The picture painted of them in the media, even when it is sympathetic is often a caricature; distance and the frenetic pace of our society break the camaraderie with the friends that they served alongside. Remarque wrote, “We were all at once terribly alone; and alone we must see it through.”

If we wonder about the suicide epidemic among veterans we have to ask hard questions. Questions like why do so many combat veterans have substance abuse problems and why is it that approximately one in ten prisoners serving time are veterans? It cannot be simply that they are all bad eggs. Many were and are smart, talented, compassionate and brave, tested and tried in ways that our civilian society has no understanding for or clue about. In fact to get in the military most had to be a cut above their peers. We have to ask if we are bringing our veterans home from war in a way that works. Maybe even more importantly we have to ask ourselves if as a culture if we have forgotten how to care about each other. How do we care for the men and women who bear the burden of war, even while the vast majority of the population basks in the freedom and security provided by the soldier without the ability to empathize because they have never shared that experience.

For every Tom Sitsch, Charles Whittlesey or people like my friend, there are countless others suffering in silence as a result of war. We really have to ask hard questions and then decide to do something as individuals, communities and government to do something about it. If we don’t a generation will suffer in silence.

Peace

Padre Steve+