Enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law in Boston

Friends of Padre Steve’s World

Today the third installment of a three part series of my work dealing with American Slavery in the ante-bellum period. These next articles deal with the subject of what happens when laws are made that further restrict the liberty of already despised, or enslaved people. In this case the subject is the Compromise of 1850 and its associated laws such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

This is an uncomfortable period of history for Americans with either a sense of conscience, or those who believe the racist myths surrounding the “Noble South” and “The Lost Cause.” I hope that you find them interesting, especially in light of current events in the United States.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

Robert Toombs of Georgia was an advocate for the expansion of slavery into the lands conquered during the war. Toombs warned his colleagues in Congress “in the presence of the living God, that if you by your legislation you seek to drive us from the territories of California and New Mexico, purchased by the common blood and treasure of the whole people…thereby attempting to fix a national degradation upon half the states of this Confederacy, I am for disunion.” [1]

The tensions in the aftermath of the war with Mexico escalated over the issue of slavery in the newly conquered territories brought heated calls by some southerners for secession and disunion. To preserve the Union, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, supported by the new President Millard Fillmore were able to pass the compromise of 1850 solved a number of issues related to the admission of California to the Union and boundary disputes involving Texas and the new territories. But among the bills that were contained in it was the Fugitive Slave Law, or The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The act was the device of Henry Clay which was meant to sweeten the deal for southerners. The law would “give slaveholders broader powers to stop the flow of runaway slaves northward to the free states, and offered a final resolution denying that Congress had any authority to regulate the interstate slave trade.” [2]

A Warning to Blacks in Boston regarding the Fugitive Slave Law

For all practical purposes the Compromise of 1850 and its associated legislation nationalized the institution of slavery, even in Free States. It did this by forcing all citizens to assist law enforcement in apprehending fugitive slaves. It also voided state laws in Massachusetts, Vermont, Ohio, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island, which barred state officials from aiding in the capture, arrest or imprisonment of fugitive slaves. “Congress’s law had nationalized slavery. No black person was safe on American soil. The old division of free state/slave state had vanished….” [3] If there was any question as to whose “States Rights” the leaders of the South were advocating, it was certainly not those of the states whose laws were voided by the act.

That law required all Federal law enforcement officials, even in non-slave states to arrest fugitive slaves and anyone who assisted them, and threatened law enforcement officials with punishment if they failed to enforce the law. The law stipulated that should “any marshal or deputy marshal refuse to receive such warrant, or other process, when tendered, or to use all proper means diligently to execute the same, he shall, on conviction thereof, be fined in the sum of one thousand dollars.” [4] In effect the law nullified state laws and forced individual citizens and local officials to help escaped slaves regardless of their own convictions, religious views, and state and local laws to the contrary.

Likewise the act compelled citizens in Free states to “aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law, whenever their services may be required….” [5] Penalties were harsh and financial incentives for compliance attractive.

“Anyone caught providing food and shelter to an escaped slave, assuming northern whites could discern who was a runaway, would be subject to a fine of one thousand dollars and six months in prison. The law also suspended habeas corpus and the right to trial by jury for captured blacks. Judges received a hundred dollars for every slave returned to his or her owner, providing a monetary incentive for jurists to rule in favor of slave catchers.” [6]

The law gave no protection for even black freedmen, who simply because of their race were often seized and returned to slavery. The legislation created a new extra-judicial bureaucratic office to decide the fate of blacks. This was the office of Federal Commissioner and it was purposely designed to favorably adjudicate the claims of slaveholders and their agents, and to avoid the normal Federal Court system. There was good reason for the slave power faction to place this in the law, many Federal courts located in Free States often denied the claims of slave holders, and that could not be permitted if slavery was to not only remain, but to grow with the westward expansion of the nation.

When slave owners or their agents went before these new appointed commissioners, they needed little in the way of proof to take a black back into captivity. The only proof or evidence other than the sworn statement by of the owner with an “affidavit from a slave-state court or by the testimony of white witnesses” [7] that a black was or had been his property was required to return any black to slavery. The affidavit was the only evidence required, even if it was false.

Since blacks could not testify on their own behalf and were denied legal representation before these commissioners, the act created an onerous extrajudicial process that defied imagination. Likewise, the commissioners had a strong a financial incentive to send blacks back to slavery, unlike normal courts the commissioners received a direct financial reward for returning blacks to slave owners. “If the commissioner decided against the claimant he would receive a fee of five dollars; if in favor ten. This provision, supposedly justified by the paper work needed to remand a fugitive to the South, became notorious among abolitionists as a bribe to commissioners.” [8] It was a system rigged to ensure that African Americans had no chance, and it imposed on the citizens of Free states the legal obligation to participate in a system that many wanted nothing to do with.

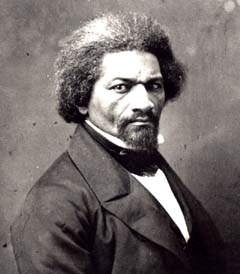

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass wrote about the new law in the most forceful terms:

“By an act of the American Congress…slavery has been nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form. By that act, Mason & Dixon’s line has been obliterated;…and the power to hold, hunt, and sell men, women, and children remains no longer a mere state institution, but is now an institution of the whole United States.” [9]

Douglass was correct as was demonstrated during an incident in Boston in 1854 where an escaped slave named Anthony Burns, who had purchased his freedom, was arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act. The arrest prompted a protest in which, “an urban mob – variously composed of free Negro laborers, radical Unitarian ministers, and others – gathered to free him. They stormed the Federal courthouse, which was surrounded by police and wrapped in protective chains….Amid the melee, one protestor shot and killed a police deputy.” [10] The heated opposition to Burns’ arrest provoked the passions of thousands of Bostonians who protested for his release that caused the Massachusetts governor to deploy two batteries of artillery outside the courthouse to deter any more attacks. When the Federal Fugitive Slave Law commissioner consigned Burns to his Southern owner, the prisoner placed in shackles and was marched down State Street. Tensions were now running extremely high and a “brigade of Massachusetts militia and local police were required to run Burns through a gauntlet and deposit him on the ship that would remand him to Virginia.” [11] Bostonians began to see their city as it was in the early days of the American Revolution, as a place that resisted tyranny. Neither did they did not forget Burns but raised the money to purchase his freedom. William Lloyd Garrison wrote, “the “deed of infamy… demonstrated as nothing else that “only “the military power of the United States” could sustain slavery.” [12] Nevertheless, Boston’s “mercantile elite had vindicated law and order” [13] but in the process they helped move so abolitionists who had been advocates of pacifism and non-violence to physical resistance to the bounty hunting Southerners. “Across the North, prisons were broken into, posses were disrupted, and juries refused to convict.” [14]

Violence between slave hunters and their protectors did break out in September 1851 when “a Maryland slave owner named Edward Gorsuch crossed into Pennsylvania in pursuit of four runaways.” [15] Gorsuch and his armed posse found them in the Quaker town of Christiana, where they were being sheltered by a free black named William Parker and along with about two dozen other black men armed with a collection of farm implements and a few muskets who vowed to resist capture. Several unarmed Quakers intervened and recommended that Gorsuch and his posse leave for their own sake, but Gorsuch told them “I will have my property, or go to hell.” [16] A fight then broke out in which Gorsuch was killed and his son seriously wounded, and the fugitives escaped through the Underground Railroad to Canada.

The Christiana Riot as it is called now became a national story. In the North it was celebrated as an act of resistance while it was decried with threats of secession in the South. President Millard Fillmore sent in troops and arrested a number of Quakers as well as more than thirty black men. “The trial turned into a test between two cultures: Southern versus Northern, slave versus free.” [17] The men were charged with treason but the trial became a farce as the government’s case came apart. After a deliberation of just fifteen minutes, “the jury acquitted the first defendant, one of the Quakers, the government dropped the remaining indictments and decided not to press other charges.” [18] Southerners were outraged, and one young man whose name is forever linked with infamy never forgot. A teenager named John Wilkes Booth was a childhood friend of Gorsuch’s son Tommy. “The death of Tommy Gorsuch’s father touched the young Booth personally. While he would move on with his life, he would not forget what happened in Christiana.” [19]

The authors of the compromise had not expected such resistance to the laws. On his deathbed Henry Clay, who had worked his entire career to pass compromises in order to preserve the Union, praised the act, of which he wrote “The new fugitive slave law, I believe, kept the South in the Union in ‘fifty and ‘fifty-one. Not only does it deny fugitives trial by jury and the right to testify; it also imposes a fine and imprisonment upon any citizen found guilty of preventing a fugitive’s arrest…” Likewise Clay depreciated the Northern opposition and condemned the attempt to free Anthony Burns, noting “Yes, since the passage of the compromise, the abolitionists and free coloreds of the North have howled in protest and viciously assailed me, and twice in Boston there has been a failure to execute the law, which shocks and astounds me…. But such people belong to the lunatic fringe. The vast majority of Americans, North and South, support our handiwork, the great compromise that pulled the nation back from the brink.” [20]

While the compromise had “averted a showdown over who would control the new western territories,” [21] it only delayed disunion. In arguing against the compromise South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun realized that for Southerners it did not do enough to support the peculiar institution and that it would inspire Northern abolitionists to redouble their efforts to abolish slavery. Thus, Calhoun argued not just for the measures secured in the compromise legislation, but for the permanent protection of slavery:

“He understood that slavery stood at the heart of southern society, and that without a mechanism to protect it for all time, the Union’s days were numbered.” Almost prophetically he said “I fix its probable [breakup] within twelve years or three presidential terms…. The probability is it will explode in a presidential election.” [22]

Of course it was Calhoun and not the authors of the compromise who proved correct. The leap into the abyss of disunion and civil war had only been temporarily avoided. However, none of the supporters anticipated what would occur in just six years when a “train of unexpected consequences would throw an entirely new light on the popular sovereignty doctrine, and both it and the Compromise of 1850 would be wreaked with the stroke of a single judicial pen.” [23]

To be continued…

Notes

[1] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning pp.62-63

[2] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.68

[3] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.71

[4] ______________Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 retrieved from the Avalon Project, Yale School of Law http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/fugitive.asp 11 December 2014

[5] Ibid. Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

[6] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.71

[7] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.80

[8] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.80

[9] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.72

[10] Goodheart, Adam 1861: The Civil War Awakening Vintage Books a division of Random House, New York 2011 p.42

[11] Ibid. Varon Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War 1789-1858 p.241

[12] Mayer, Henry All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery W.W. Norton and Company, New York and London 1998 p.442

[13] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.84

[14] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.73

[15] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.73

[16] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.84

[17] Steers, Edward Jr. Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln The University of Kentucky Press, Lexington 2001 p.33

[18] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.85

[19] Ibid. Steers Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln p.33

[20] Oates, Stephen B. Editor The Approaching Fury: Voices of the Storm, 1820-1861 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 1997 p.94

[21] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.71

[22] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.64

[23] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.71

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

Pingback: Enforcing White Privilege: The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and “the Privilege of Belonging to the Superior Race Part Three | Padre Steve's World...Musings of a Progressive Realist in Wonderland

Pingback: The Disadvantages Of Belonging To Supposedly Inferior Races, Part Three: When Law is Opposed to Justice | Padre Steve's World: Official Home of the Anti-Chaps

Pingback: It’s Not Just Old History: The Fugitive Slave Act Of 1850 at 179 Years | Padre Steve's World: Official Home of the Anti-Chaps