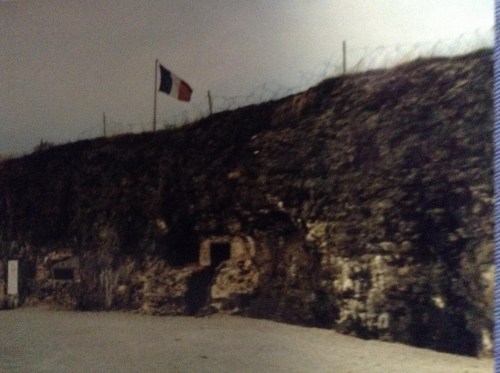

Fort Vaux, Verdun France, 1984

Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

Many Americans are infatuated with the Second World War. I think this is because it is closer to us and how it has been recorded in history and film. I think much of this is due to the resurgence of popular works such as Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation, Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers and the associated classic mini-series, and Steven Spielberg’s cinema classic Saving Private Ryan. Of course there were many other books and films one World War Two that came out even during the war that made it an iconic event in the lives of Americans born in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. In fact I have many of the books and videos in my library.

But as pervasive as is the literary and filmography of the Second War War remains, the fact is that the First World War is much more important in a continuing historical sense than the Second World War. Edmond Taylor, the author of the classic account The Fall of the Dynasties: 1905-1922 wrote:

“The First World War killed fewer victims than the Second World War, destroyed fewer buildings, and uprooted millions instead of tens of millions – but in many ways it left even deeper scars both on the mind and on the map of Europe. The old world never recovered from the shock.”

First World War is far too often overlooked in our time, yet it was the most important war in the effects that still resonate today. One cannot look at the Middle East, Africa, the Balkans, or Eastern Europe without recognizing that fact. A similar case can be made in Asia where Japan became a regional power capable of challenging the great powers in the Pacific by its participation on the side of the Allies in that war. The same is true of the United States, although in the aftermath of the war it retreated into a narcissistic isolationism that took Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor to break.

But I digress. The purpose I have tonight it to recommend some books and films that I think are helpful in understanding just how important the First World War remains to us today.

I made my first visit to a World War One battlefield when I went to Verdun in 1984. I was a young Army Second Lieutenant, preparing myself for time time that the Red Army would attack across the Fulda Gap. The walk around the battlefield was one of the most sobering events of my life. It was hard to imagine that a minimum of 700,000 German and French soldiers were killed or wounded on this relatively small parcel of ground over a period of nine months in 1916. The fact that many parts of the battlefield are off limits to visitors due to the vast amount of unexploded ordnance and persistent chemical agents, in this gas Mustard Gas also made an impression on me. But what affected me most was unearthing a bone fragment as I shuffled my feet near Fort Vaux and turning it over to a docent. I am sure that it was added to the Ossuary which contains the skeletal remains of over 130,000 French and German soldiers. It is hard to forget.

Barbara Tuchman wrote:

“Books are the carriers of civilization. Without books, history is silent, literature dumb, science crippled, thought and speculation at a standstill. Without books, the development of civilization would have been impossible. They are engines of change (as the poet said), windows on the world and lighthouses erected in the sea of time. They are companions, teachers, magicians, bankers of the treasures of the mind. Books are humanity in print.”

The literature that came out of the First World War by participants or observers, either as memoirs, works of fiction, or poems is impressive. Likewise the volumes chronicled by soldiers which influenced later military strategic, operational, and tactical developments between the World Wars remains with us today. In fact the military works still remain the basis for much of the current understanding of combined arms, counterinsurgency, and mission command doctrine.

More importantly, and perhaps less appreciated by policy makers and strategists are the personal works of soldiers that fought the in the great battles along the western front during the war. For the most part, the soldiers who served on the Western Front, the Balkans, Italy, and the Eastern Front are part of an amorphous and anonymous mass of people who simply became numbers during the Great War, thus the individual works of men like John McRea, Sigfried Sassoon, Erich Maria Remarque, Winfried Owen, Ernst Junger, Erwin Rommel, and even Adolf Hitler, are incredibly important in understanding the war, the ideology, and the disappointment of the men who served in the trenches. This applies regardless of the particular writer’s experience or political ideology.

The fact is that very few men who served on the ground in Europe reached the distinction of individual recognition is remarkable. More often those who achieved fame as relatively low ranking individuals were the Knights of the Air, the aviators who in individual combat above the trenches were immortalized by friend and foe alike. These men were represented as an almost mythological portrait of chivalry in a war where millions of men died anonymously, riddled by machine gun fire, artillery, and poison gas in mud saturated ground, trenches, and no man’s land. There are war cemeteries in France and Belgium where the majority of those interred are unknowns. On the Eastern Front, even those cemeteries and memorials are sparse, swallowed by war, shifting borders, and massive forced population migrations between 1918 and 1948.

For different reasons the books and poems written by the otherwise anonymous soldiers in Europe are important if we are to understand the world that we have inherited and must live in today. The same is true of men like T. E. Lawrence who served in the Middle East, or his East African counterpart, the German Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. Both of them made their names by conducting inventive campaigns using indigenous irregular soldiers to tie down and defeat far stronger opponents.

Histories and biographies written about the period by later historians using the documents and words of the adversaries, as well as solid hermeneutics and historiography are also quite important. So are the analysis of economists, sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, and even theologians as to the effects of the war on us today, but I digress.

Tonight I will list a number of books, poems, and films that I think are important in interpreting the Great War, especially, in trying to understand just how the men who directed and fought that war set the stage for today.

Lawrence’s “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” as well as many of his post-war letters, articles, and opinion pieces help us understand the current Middle East through the lens of a brilliant but deeply troubled man. Remarque, Sassoon, McRea, Junger, Owen, and Hitler help us to understand the ideology, motivations, fears, and hopes of men on different sides and even very different ideological and political points of view. Now I would not recommend Hitler’s poorly written, turgid, almost unreadable, and hate filled book to anyone but a scholar of the period or biographer the the Nazi dictator.

Later historians Barbara Tuchman, Holger Herweg, Edmond Taylor, Richard Watt, and Robert Massie help us understand that bigger picture of international politics, intrigue, and strategy. Lest to be trusted, are the memoirs of high ranking men of any side who helped to write, and re-write the history of the war and its aftermath in order to bolster their own historical credibility. The same is true of the men who urged on war in 1914 and retreated from that in 1918 as if they had never heard of the war.

As for the books that came out of the war I would have to recommend Lawrence’s classic Seven Pillars of Wisdom, as well as articles, and letters, written by him available online at T. E. Lawrence Studies . Likewise, Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front is a classic account of a combat soldier with a distinct anti-war message. Junger’s Storm of Steel is also an account of a combat soldier who came out of the war but with a message completely different than Remarque’s. The poetry of the British Soldiers McRea, Sasson, and Owen is moving and goes to the heart of the war experience in a way that prose, no matter how well written cannot do.

Of the later histories I think that Taylor’s The Fall of the Dynasties, The Collapse of the Old Order, 1905-1922, Tuchman’s The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War, 1890-1914 and The Guns of August, Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War In 1914, and Margaret McMillen’s The War that Ended Peace: The Road to 1914, are essential to understanding the events and conditions leading up to the war.

Herweg’s World War One and Massie’s Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea are both good accounts of the war. Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War by Max Hastings, and Home Before the Leaves Fall: A New History of the German Invasion of 1914, by Ian Senior, and Tannenberg: Clash of Empires by Dennis Showalter are excellent recent histories of the opening months of the war which are a good compliment to Tuchman’s The Guns of August.

Books about battles and campaign outside of the opening months and general histories of the war I have to admit that I have not read many. Most of the ones I have read deal with the ordeal and crisis of the French Army in 1916 and 1917. Alistair Horne’s The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916, Richard Watt’s Dare Call it Treason, and David Murphy’s The Breaking Point of the French Army: The Neville Offensive of 1917 document the valor, sacrifice, and near collapse of the French Army.

A book that is focuses on the American military in the war and how it helped change American society is Jennifer Keene’s Doughboys: The Great War and the Making of American Society.

A book that I found interesting was Correlli Barnett’s The Sword-bearers: Supreme Command in the First World War. The book provides short biographies of the lives and influences of German Field Marshal Von Moltke, British Admiral Jellicoe, French General Petain, and German General Ludendorff. It is a good study in command. Another biography that I recommend is

As for the war at sea, I recommend Edwin Hoyt’s The Last Cruise of the Emden, R. K. Lochner’s The Last Gentleman of War: The Raider Exploits of the Cruiser Emden, Geoffrey Bennett’s Coronel and the Falklands, Holger Herweg’s Luxury Fleet: The Imperial German Navy, 1888 – 1918 in addition to Massie’s Castle’s of Steel, of which the latter is probably the best resource for the naval aspects of the war.

A couple of books that deal with the often overlooked campaign in East Africa are Lettow Von Vorbeck’s My Reminiscences of East Africa, and Königsberg: A German East Africa Raider by Kevin Patience shed light on this obscure but important campaign.

Erwin Rommel’s Infanterie Greift An (Infantry Attacks) is quite possibly the best book on tactics and operational methods published by a participant. Likewise, the the British historians and theoreticians B. H. Liddell-Hart and J. F. C. Fuller, and German Panzer theorist and Commander Heinz Guderian, who also served on the front produced a number of volumes which influenced later strategic and operational advancements which are still in evidence today.

Watt’s The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany: Versailles and the German Revolution is a necessity if one is to understand the rise of the Nazi State. Likewise, a good resource of the deliberations leading to the Treat of Versailles is Margaret McMillen’s 1919: Six Months that Changed the World. Related to this is the very interesting account of the scuttling of the interred German High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow in the aftermath of Versailles, The Grand Scuttle: The Sinking of the German Fleet at Scapa Flow In 1919 by Dan Van der Vat.

One work of fiction that I can recommend is The General by C. S. Forester.

I am sure that there are many other volumes that others could recommend, but these are mine.

In an age where there are many parallels to the years leading up to the Great War, it is important not to forget just how catastrophic such a war can be.

So until tomorrow,

Peace,

Padre Steve+

For some reason this year I was drawn to know more about WWI. Perhaps it was trump’s lack of respect for these men and other veterans that in a perverse way caught my attention.

My favorite genre is historical fiction rather than the dryness of non fiction. So I would appreciate any recommendations from you.

I like books with characters that become real and feelings and beautiful prose and flow in a book. I did read Jeff Shara’s trilogy, but I was looking for something deeper. As for WWII, I particularly like Herman Wouk’s Winds of War and War and Remembrance. This is the style I like. The characters bring it alive for me. I don’t want tactical advice and strategy books.

Thanks for any suggestions.