Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

Today marks the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Midway, the epic “David versus Goliath” battle that ended Japan’s chance to win World War Two in the Pacific. It was a battle where skill, luck, good fortune and courage combined to allow the United States Navy to deliver a crushing defeat the previously undefeated Kido Butai, the Japanese First Carrier Striking Force which had run rampant across the Pacific and Indian Oceans in the six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Today, the youngest survivors of the battle are over ninety years old. Their generation, like the rest of what we remember as the Greatest Generation will soon pass from the bonds of this earth into eternity. As you read this remember their sacrifice and too remember the tragedy of the Japanese sailors and airmen that were lost at Midway due to their government’s aggression against their neighbors throughout Asia that led to their attack on the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

Peace

Padre Steve+

Prelude to Battle

The Imperial Japanese Navy under the command of Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto had been humiliated. On April 18th 1942 16 B-25 bombers under the command of Colonel Jimmy Doolittle were launched from the deck of the USS Hornet and bombed Tokyo. Though the physical damage was insignificant the psychological impact was massive on the Japanese military establishment. In response to the threat, Yamamoto was directed to bring the aircraft carriers of the U.S. Navy to battle and to destroy them.

Prior to the Doolittle Raid, Yamamoto and his deputy Rear Admiral Matome Ugaki had explored the possibility of attacking Midway. However, the Japanese armed forces were competing with each other to determine an overall strategy for the war effort. The Army was insistent on a China strategy while the Navy preferred expansion in the Western, South and Central Pacific. Yamamoto’s idea envisioned seizing Midway and using it as a forward base from which an invasion of Hawaii could be mounted as well as the bait to draw the carrier task forces of the U.S. Navy into battle and destroy them. Until the Doolittle Raid shocked the Japanese leadership he was unable to do this.

“I Shall Run Wild for the First Six Months”

Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto

Yamamoto was one of the few Japanese military or political leaders who opposed war with the United States. He had lived in the United States, gotten to know Americans and recognized the how the massive economic and industrial power of the United States would lead to the defeat of Japan. He told Premier Konoye in 1941 “I shall run wild for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second or third years of the fighting.”

It is hard to imagine now, but in June of 1942 it seemed a good possibility that the Americans and British could be on the losing side of the Second World War.

True to Yamamoto’s words in 1942 the Japanese onslaught in the Pacific appeared nearly unstoppable. The Imperial Navy stormed across the Pacific and Indian Oceans in the months after Pearl Harbor decimating Allied Naval forces that stood in their way. The British Battleships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse were sunk by land based aircraft off of Singapore. A force of Royal Navy cruisers and the Aircraft Carrier HMS Hermes were sunk by the same carriers that struck Pearl Harbor in the Indian Ocean. Darwin Australia was struck with a devastating blow on February 19th and on February 27th the Japanese annihilated the bulk of the American, British, Dutch and Australian naval forces opposing them at the Battle of the Java Sea. American forces in the Philippines surrendered on May 8th 1942 while the British in Singapore surrendered on February 15th.

In only one place had a Japanese Naval task force been prevented from its goal and that was at the Battle of the Coral Sea. Between 4-8 May the US Navy’s Task Force 11 and Task Force 17 centered on the Carriers USS Lexington and USS Yorktown prevented a Japanese invasion force from taking Port Moresby. Their aircraft sank the light carrier Shoho, damaged the modern carrier Shokaku and decimated the air groups of the Japanese task force. But it was the unexpected raid by US Army Air Corps B-25 Bombers launched from the USS Hornet under command of Colonel Jimmy Doolittle on April 18th 1942 which embarrassed Yamamoto so badly that he ordered the attack to take Midway and destroy the remaining US Naval power in the Pacific.

Cracking the Code

Admiral Chester Nimitz

United States Navy codebreakers had broken the Japanese diplomatic and naval codes in 1941, and in May the Navy code breakers under the command of Commander Joseph Rochefort at Pearl Harbor discovered Yamamoto’s plan to have the Imperial Navy attack Midway Island and the Aleutian Islands. Knowing the Japanese were coming, and that the occupation of Midway by Japanese forces would give them an operational base less than 1000 miles from Pearl Harbor, Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet committed the bulk of his naval power, the carriers USS Enterprise CV-6, USS Yorktown CV-5 and USS Hornet CV-8 and their 8 escorting cruisers and 15 destroyers to defend Midway. This force of 26 ships with 233 aircraft embarked to defend Midway while a force of smaller force 5 cruisers and 4 destroyers was dispatched to cover the Aleutians. The forces on the ground at Midway had a mixed Marine, Navy and Army air group of 115 aircraft which included many obsolete aircraft, 32 PBY Catalina Flying Boats and 83 fighters, dive bombers, torpedo planes and Army Air Force bombers piloted by a host of inexperienced but resolute airmen with which to defend it. It also had a ground force of U.S. Marines, should the Japanese actually land on the island.

With the foreknowledge provided by the code breakers the US forces hurried to an intercept position northeast of Midway. They eluded the Japanese submarine scout line which the Japanese Commander Admiral Yamamoto presumed would find them when they sailed to respond to the Japanese attack on Midway. Task Force 16 with the Enterprise and Hornet sailed first under the command of Rear Admiral Raymond A Spruance in place of the ailing William “Bull” Halsey. Task Force 17 under Rear Admiral Frank “Jack” Fletcher was built around the Yorktown which had been miraculously brought into fighting condition after suffering heavy damage at Coral Sea. Fletcher assumed overall command by virtue of seniority and Admiral Nimitz instructed his commanders to apply the principle of “calculated risk” when engaging the Japanese as the loss of the US carriers would place the entire Pacific at the mercy of the Japanese Navy.

On June 3rd a PBY Catalina from Midway discovered the Japanese invasion force transport group. US long-range B-17 bombers launched attacks against these ships but inflicted no damage.

“Our hearts burn with the conviction of sure victory.”

On the night of June 3rd 1942 Nagumo’s First Carrier Strike Force sailed east toward the tiny Midway Atoll. Nagumo had seen many of the risks involved in the plan and considered it an “impossible and pointless operation” before the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo, but even the reluctant Nagumo fell in line as Yamamoto relentlessly lobbied for the operation.

As the First Carrier strike force closed within 300 miles of Midway on the night of June 3rd 1942 Nagumo and his staff prepared for the battle that they and many others believed would be the decisive battle. Aircraft received their final preparations, bombs were loaded and as night faded into early morning air crew arose, ate their breakfast and went to their aircraft. The ships had been observing radio silence since they departed their bases and anchorages in Japan the previous week. Honed to a fine edge the crews of the ships and the veteran aircrews anticipated victory.

The crews of the ships of the task force and the air groups embarked on the great aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu as well as their escorts were confident. They had since the war began known nothing but victory. They had devastated the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and roamed far and wide raiding allied targets and sinking allied shipping across the Pacific and deep into the Indian Ocean. Commander Magotaro Koga of the destroyer Nowaki wrote in his diary “Our hearts burn with the conviction of sure victory.”

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo

However, Nagumo and his sailors had no idea that most of what they knew about their American opponents was wrong. Nagumo and Yamamoto were confident that the Americans could field no more than two operational carriers to defend Midway. They had no idea that the Yorktown, which they believed had been sunk at Coral Sea was operational and her air group reinforced by the aircraft of the damaged Saratoga which was being repaired on the West Coast. Unknown to the Japanese the Yorktown and her escorts had joined Enterprise and Hornet northeast of Midway.

The Japanese were going into battle blind. They had planned to get aerial surveillance of US Fleet dispositions at Pearl Harbor, but that had been cancelled because the atoll at French Frigate Shoals that the Japanese flying boats would operate from had been occupied by a small US force. Likewise a line of Japanese submarines arrived on station a day too late, after the US carrier task forces had passed by them. Those aboard the First Carrier Strike Force, including Nagumo or his senior commanders and staff had no idea that the Americans not only knew of their approach but were already deployed in anticipation of their strike.

Within a day all of the Japanese carriers would be sunk or sinking. Thousands of Japanese sailors would be dead and the vaunted air groups which had wreaked havoc on the Allies would be decimated, every aircraft lost and the majority of pilots and aircrew dead. It would be a most unexpected and devastating defeat stolen out of the hands of what appeared to be certain victory.

There is a lesson to be learned from the Japanese who sailed into the night on June 3rd 1942 and saw the sunrise of June 4th. There is no battle, campaign or war that goes according to plan. Thousands of Japanese sailors and airmen went to bed on the night of the 3rd expecting that the following night, or within the next few days they would be celebrating a decisive victory. Thousands of those sailors would be dead by the night of the 4th of June 1942, and as their ships slid beneath the waves, the ambitions of Imperial of Japan to defeat the United States Navy and end the war were dealt a decisive defeat from which they never recovered.

Hawks at Angles Twelve

One of the more overlooked aspects of the Battle of Midway is the sacrifice of Marine Fighter Squadron 221 on the morning of June 4th 1942. The Marine aviators flying a mix of 21 obsolescent Brewster F2A-3 Buffalos and 7 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats engaged a vastly superior force of Japanese Navy aircraft as they vectored toward the atoll to begin softening it up for the planned invasion.

Led by Major Floyd Parks the squadron had arrived at Midway on Christmas day 1941 being delivered by the USS Saratoga after the aborted attempt to relieve Wake Island. The squadron along with Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 241 (VMSB 241) formed Marine Air Group 22. They fighter pilots of VMF-221 scored their first victory shooting down a Japanese Kawanishi H8K2 “Emily” flying boat. The squadron which initially was composed of just 14 aircraft, all F2A-3’s was augmented by 7 more F2A-3s and 7 of the more advanced F4F-3s before the battle.

When the Japanese First Carrier Striking Group was spotted in the wee hours of June 4th the Marines and other aircrew aboard Midway scrambled to meet them. The 18 SBD-2 Dauntless’ and 12 Vought SB2-U3 Vindicator dive bombers of VMSB-241, the 6 TBF Avengers of the Navy Torpedo Eight detachment, 4 Army Air Corps B-26 Marauders and 15 B-17 Flying Fortresses flew out to attack the Japanese carriers while the fighters rose to intercept the 108 aircraft heading toward Midway. The 72 strike aircraft, 36 Aichi 99 Val Dive Bombers and 36 Nakajima B5N Torpedo/ High Level Bombers were protected by 36 AM6-2 Zeros which thoroughly outclassed the Marine opponents in speed, maneuverability and in the combat experience of their pilots.

The Marine fighters audaciously attacked the far superior Japanese force, throwing themselves against the Japanese phalanx with unmatched courage. Despite their courage the Marine fighters were decimated by the Japanese Zeros. The Marines shot down 4 Val dive bombers and at least three Zeros but lost 13 Buffalos and 3 Wildcats during the battle. Of the surviving aircraft only three Buffalos and three Wildcats were in commission at the end of the day. Among the casualties killed was Major Parks. Of the surviving pilots of VMF-221, two became “Aces” during the war. Lieutenant Charles M. Kunz would later fly in VMF-224, adding six victories to end the war with 8 victories. Capt. Marion E. Carl would later fly in VMF-223 raising his score to 18.5 Japanese aircraft shot down. Other pilots like 2nd Lieutenant Clayton M. Canfield shot down two additional aircraft while flying with VMF-223. 2nd Lieutenant Walter W. Swansberger won the Medal of Honor at Guadalcanal.

The last remaining Marine fighter pilot of VMF-221 from the battle of Midway, Williams Brooks died in January 2010 and was buried with full military honors, in Bellview, Nebraska. Brooks in his after action report described his part in the battle:

I was pilot of F2A-3, Bureau number 01523, Our division under Capt. Armistead was on standby duty at he end of the runway on the morning of June 4, 1942, from 0415 until 0615. At about 0600, the alarm sounded and we took off. My division climbed rapidly, and I was having a hard time keeping up. I discovered afterwards that although my wheels indicator and hydraulic pressure indicator both registered “wheels up”, they were in reality about 1/3 of the way down. We sighted the enemy at about 14,000 feet, I would say that there were 40 to 50 planes. At this time Lt. Sandoval was also dropping back. My radio was at this time putting out no volume, so I could not get the message from Zed. At 17,000 feet, Capt. Armistead led the attack followed closely by Capt. Humberd. They went down the left of the Vee , leaving two planes burning. Lt. Sandoval went down the right side of the formation and I followed. One of us got a plane from the right side of the Vee. At this time, I had completely lost sight of my division. As I started to pull up for another run on the bombers, I was attacked by two fighters. Because my wheels being jammed 1/3 way down, I could not out dive these planes, but managed to dodge them and fire a burst or so into them as they went past me and as I headed for the water. As I circled the island, the anti-aircraft fire drove them away. My tabs, instruments and cockpit were shot up to quite an extent at this time and I was intending to come in for a landing.

It was at this time that I noticed that a important feature in their fighting. I saw two planes dog-fighting over in the east, and decided to go help my friend if at all possible. My plane was working very poorly, and my climb was slow. As I neared the fight both planes turned on me. It was then that I realized I had been tricked in a sham battle put on by two Japs and I failed to recognize this because of the sun in my eyes. Then I say I was out-numbered, I turned and made a fast retreat for the island, collecting a goodly number of bullets on the way. After one of these planes had been shaken, I managed to get a good burst into another as we passed head-on when I turned into him. I don’t believe this ship could have gotten back to his carrier, because he immediately turned away and started north and down. I again decided to land, but as I circled the island I saw two Japs on a Brewster. Three of my guns were jammed, but I cut across the island, firing as I went with one gun. But I could not get there in time to help the American flier and as soon as the Brewster had gone into the water I came in for a landing at approximately 0715 (estimated).

As for VMF-221 it was re-equipped with the F4F-4 and later with the F4U Corsair during the course of two more deployments overseas. VMF-221 finished the war with a score of 155 victories, 21 damaged and 16 probable kills, the second highest total of any Marine Corps Squadron during the war.

Their bomber counterparts of VMSB 241 attacked the Japanese task force on the morning of June 4th and scored no hits while losing 8 aircraft. The survivors were again in action later in the day as well as the following day where they helped sink the Japanese Heavy Cruiser Mikuma with their squadron leader Major Henderson diving his mortally wounded aircraft into the cruiser’s number 4 8” gun turret. While the Marines’ actions are not as well known or as successful as those of their Navy counterparts they were brave. Fighter pilots had to engage some of the most experienced pilots flying superior machines while the bomber crews had little to no experience before being thrown into combat.

Into the Valley of Death: The Last Ride of the Torpedo Bombers

Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote in the Charge of the Light Brigade something that echoes to this day when we talk or write about men who charge the gates of death against superior enemies.

Half a league half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred:

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns’ he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

They were not six hundred and they were not mounted on horses, but the Naval Aviators of Torpedo Squadrons 3, 6 and 8 and their aerial steeds 42 Douglas TBD Devastators and 6 TBF Avengers wrote a chapter of courage and sacrifice seldom equaled in the history of Naval Aviation. Commanded by veteran Naval Aviators, LCDR Lance “Lem” Massey, LCDR Eugene Lindsey and LCDR John Waldron the squadrons embarked aboard the carriers flew the obsolete TBD Devastators. The young pilots of the Midway based Torpedo 8 detachment under the command of LT Langdon Fieberling flew in the new TBF Avengers.

The TBD which first flew in 1935 entered service in 1937 and was possibly the most modern naval aircraft in the world when it entered service. It was a revolutionary aircraft. It was the first monoplane widely used on carriers and was first all-metal naval aircraft. It was the first naval aircraft with a totally enclosed cockpit, the first with hydraulic powered folding wings. The TBD had crew of three and had a maximum speed of 206 miles an hour and carried a torpedo or up to 1500 pounds of bombs (3 x 500) or a 1000 pound bomb. 129 were built and served in all pre-war torpedo bombing squadrons based aboard the Lexington, Saratoga, Ranger, Yorktown, Enterprise and Hornet with a limited number embarked aboard Wasp.

The Devastator saw extensive service prior to the war which pushed many airframes to the end of their useful service life and by 1940 only about 100 were operational by the beginning of the war. They were still in service in 1942 as their replacement the TBF Avenger was not available for service in large enough numbers to replace them before Midway. The TBDs performed adequately against minor opposition at Coral Sea and in strikes against the Marshalls but the squadrons embarked on Yorktown (VT3), Enterprise (VT-6) and Hornet (VT-8) were annihilated at Midway with only 6 of 41 aircraft surviving their uncoordinated attacks against the Japanese Carrier Strike Force. They were too slow, had poor maneuverability, insufficient armor and defensive armament.

The Torpedo squadrons attacked independently of each other between 0920 and 1030 on June 4th 1942. The Japanese Combat Air Patrol ripped into the slow, cumbersome and under armed TBD Devastators as they came in low to launch their torpedoes. Torpedo Eight from Hornet under the command of LCDR John C Waldron pressed the attack hard but all 15 of the Devastators were shot down. Only Ensign George Gay’s aircraft was able to launch its torpedo before being shot down and Gay would be the sole survivor of the squadron to be picked up later by a PBY Catalina patrol plane.

Torpedo Six from the Enterprise under the command of LCDR Eugene Lindsey suffered heavy casualties losing 10 of 14 aircraft with Lindsey being one of the casualties. The last group of Devastators to attack was Torpedo Three from the Yorktown under the command of LCDR Lem Massey losing 11 of 13 aircraft with Massey a casualty last being seen standing on the wing of his burning aircraft as it went down. These aircraft were also decimated and Massey killed but they had drawn the Japanese Combat Air Patrol down to the deck leaving the task force exposed to the Dive Bombers of the Enterprise and Yorktown. The six aircraft of the Torpedo Eight detachment from Midway under the command of LT Fieberling lost 5 of their 6 aircraft while pressing their attacks. Only Ensign Bert Earnest and his aircraft survived the battle landing in a badly damaged state on Midway. Four U.S. Army B-26 Marauder Medium Bombers were pressed into service as torpedo bombers of which 2 were lost. No torpedo bomber scored a hit on the Japanese Task force even those torpedoes launched at close range failed to score and it is believe that this was in large part due to the poor performance of the Mark 13 aircraft torpedoes.

Despite the enormous losses of the torpedo squadrons their sacrifice was not in vain. Their attacks served to confuse the Japanese command and delay the rearmament of aircraft following the Japanese strikes on Midway. They also took the Japanese Combat Air Patrol down to sea level and opened the way for American Dive Bombers to strike the Japanese with impunity fatally damaging the Akagi, Kaga and Soryu in the space of 5 minutes.

After Midway the remaining TBDs were withdrawn from active service and no example survives today. The TBF became the most effective torpedo bomber of the war and some remained in service in a civilian capacity to fight forest fires until 2012.

The Provence of Chance: Five Minutes that Changed the War

The land based aircraft from Midway attacked the Japanese carrier force taking heavy casualties and failed to damage the Japanese task force. When the results of the first strike of the Japanese bombers that hit Midway was analyzed Nagumo readied his second wave.

As this was happening the American carriers launched their strike groups at the Japanese fleet leaving enough aircraft behind as for Combat Air Patrol and Anti-submarine patrol missions. As the Americans winged toward the Japanese fleet the Japanese were in a state of confusion. The confusion was caused when a scout plane from the Heavy Cruiser Tone that had been delayed at launch discovered US ships but did not identify a carrier among them until later into the patrol. The carrier was the Yorktown and TF 17, but for Nagumo who first expected no American naval forces, then received a report of surface ships without a carrier followed by the report of a carrier the reports were unsettling.

Aboard the Japanese ships, orders and counter-orders were issued as the Japanese attempted to recover their strike aircraft and prepare for a second strike on the island, but when the Yorktown task force was discovered, orders were changed and air crews unloaded ground attack ordnance in favor of aerial torpedoes and armor piercing bombs. In their haste to get their aircraft ready to strike the Americans, the hard working Japanese aircrews did not have time to stow the ordnance removed from the aircraft. But due to their hard work at 1020 they had the Japanese strike group ready to launch against the US carriers. Aircraft and their crews awaited the order to launch, their aircraft fully armed and fully fueled.

There had been confusion among the Americans as to the exact location of the Japanese Carriers. Bombing 8 and Scouting 8 from Hornet made a wrong turn and not find the Japanese carriers. The squadrons had to return due to a lack of fuel and a number of bombers and their fighter escort had to ditch in the ocean and wait for rescue. The Enterprise group composed of Bombing-6 and Scouting 6 under CDR Wade McClusky was perilously low on fuel when they spotted the wake of a Japanese destroyer steaming at high speed to catch up with the Japanese carriers. Taking a chance, McClusky followed it straight to the Japanese Task Force arriving about 1020. The Yorktown’s group under LCDR Max Leslie arrived about the same time.

When the American dive bombers arrived over the Japanese Carrier Strike Force they found the skies empty of Japanese aircraft. Below, aboard the Japanese ships there was a sense of exhilaration as each succeeding group of attackers was brought down and with their own aircraft ready to launch and deal a fatal blow to the American carrier wondered how big their victory would be. The war would soon be decided.

At 1020 the first Zero of the Japanese attack group began rolling down the flight deck of the flagship Akagi, aboard Kaga aircraft were warming up as they were on the Soryu. The unsuspecting Japanese were finally alerted to the threat of the American dive bombers when lookouts screamed “helldivers.” The Japanese fighters assigned to the combat air patrol were flying too low as the mopped up the last of the doomed torpedo bombers and were not in a position to intercept the Americans.

Wade McClusky’s aircraft lined up over the Akagi and Kaga pushing into their dives at 1022. There was a bit of confusion when the bulk of Scouting 6 joined the attack of Bombing 6 on the Kaga. That unprepared ship was struck by four 1000 pound bombs which exploded on her flight deck and hangar deck igniting the fully fueled and armed aircraft of her strike group and the ordnance littered about the hangar deck. Massive fires and explosions wracked the ship and in minutes the proud ship was reduced to an infernal hell with fires burning uncontrollably. She was abandoned and would sink at 1925 taking 800 of her crew with her.

LT Dick Best of Scouting 6 peeled off from the attack on Kaga and shifted to the Japanese flagship Akagi. On board Akagi were two of Japan’s legendary pilots CDR Mitsuo Fuchida leader of and CDR Minoru Genda the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack and subsequent string of Japanese victories. Both officers were on the sick list and had come up from sick bay to watch as the fleet was attacked. Seeing Kaga burst into flames they stood mesmerized until Akagi’s lookouts screamed out the warning “helldivers” at 1026.

Best’s few aircraft hit with deadly precision landing two of their bombs on Akagi’s flight deck creating havoc among the loaded aircraft and starting fires and igniting secondary explosions which turned the ship into a witch’s cauldron. By 1046 Admiral Nagumo and his staff were forced to transfer the flag to the cruiser Nagara as Akagi’s crew tried to bring the flames under control. They would do so into the night until nothing more could be done and abandoned ship at 2000. Admiral Yamamoto ordered her scuttled and at 0500 on June 5th the pride of the Japanese carrier force was scuttled.

VB-3 under LCDR Max Leslie from the Yorktown stuck the Soryu with 17 aircraft, however only 13 of the aircraft had bombs due to an electronic arming device malfunction on 4 of the aircraft, including that of Commander Leslie. Despite this Leslie led the squadron as it dove on the Soryu at 1025 hitting that ship with 3 and maybe as many as 5 bombs. Soryu like her companions burst into flames as the ready aircraft and ordnance exploded about her deck. She was ordered abandoned at 1055 and would sink at 1915 taking 718 of her crew with her.

The only Japanese carrier to survive the initial assault, Hiryu continued the fight. Hiryu’s dive bombers found Yorktown and while they suffered heavy losses to the F4F Wildcats of Yorktown’s CAP, three Val’s from Hiryu scored hits which started fires and disabled Yorktown, causing her to lose power and go dead in the water. Yorktown’s damage control teams miraculously got the fires under control, patched her damaged flight deck while her engineers restored power and Yorktown was back in action steaming at a reduced speed of 20 knots but able to conduct air operations again, but the plucky Hiryu and her depleted air group were not done.

Hiryu’s second strike composed of Kate Torpedo Bombers discovered Yorktown, and since she appeared undamaged the squadron leader assumed that she was another carrier. Yorktown’s reduced CAP was unable to stop the Kates and the Japanese scored 2 torpedo hits causing another loss of power and a severe list. Thinking that she might capsize, her captain ordered that she be abandoned.

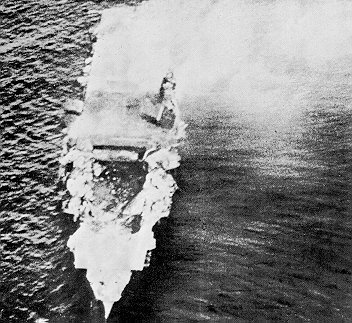

The Damaged Hiryu

As this was occurring a mixed attack group from the Enterprise and now “homeless” Yorktown aircraft attacked Hiryu. Like her sisters she was caught with her flight deck full of fueled and armed aircraft preparing for another strike against the Americans. The damage to the brave ship was mortal. Her crew abandoned ship and she sank the following day.

Yorktown would be sunk by a Japanese submarine, along with the destroyer Hamman a few days later as her crew attempted to get her to Pearl Harbor. In five pivotal minutes the course of the war in the Pacific was changed.

A Final Ignominy

Admiral Yamamoto was still attempting to digest the calamity that had befallen Admiral Nagumo’s carrier task force. In the shocked atmosphere of the mighty Super Battleship Yamato’s command center the Staff of the Combined Fleet was hastily attempting to arrive at a solution which might reverse the disaster and bring victory. Admiral Ugaki, Yamamoto’s Chief of Staff, despite strong personal doubts, ordered Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo to prepare for a night surface engagement with the US Fleet and dispatched a strong surface force to bombard Midway in order to prevent the Americans from reinforcing it and to prevent its further use against his forces should the invasion move forward. Kondo then organized his fleet to attempt to find the American carriers and bring them to battle before dawn.

Kondo detached Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita’s Close Support Group composed of Cruiser Seven, the fastest and most modern cruisers in the Imperial Navy proceed at full speed to attack Midway. Kurita’s cruisers, the Kumano, Suzuya, Mikuma and Mogami were each armed with 10 8” guns and were escorted by the two destroyers.

Kurita’s force was 80 miles from Midway when Yamamoto realizing that his plan was unrealistic ordered Kondo’s forces to retreat and rendezvous with his main force shortly after midnight. The order was met with a measure of relief by most officers in the force and the force turned northwest and steamed at 28 knots to meet the Main Body. At 0215 lookouts on Kumano sighted a submarine on the surface which turned out to be the USS Tambor which had been shadowing the group, and made a signal for the force to make a emergency 45 degree turn to port.

During the process Mogami’s Navigator took over from the watch to oversee the tricky maneuver. In doing so he thought that there was too much distance between him and the ship ahead, the Mikuma. So he adjusted his course to starboard and then realized his mistake. The ship he thought was Mikuma was actually Suzuya and Mikuma was directly ahead. As soon as he recognized his mistake Mogami’s Navigator ordered a hard turn to port and reversed the engines but it was too late. Mogami’s bow crashed into Mikuma’s port quarter. The impact caused minimal damage to Mikuma but Mogami was heavily damaged. She lost 40 feet of her bow and everything else was bent back to port at right angles to her number one turret.

Mogami’s damage control teams isolated the damage and worked the ship up to 12 knots. This was not fast enough for Kurita to make his rendezvous so he left Mikuma and the destroyers to escort Mogami while he steamed ahead with Kumano and Suzuya.

Tambor’s skipper LCDR John W Murphy sent a contact report at 0300 reporting “many unidentified ships.” He followed this with more detailed information and the Americans on Midway began to launch its remaining serviceable aircraft to attack the threat. A flight of B-17 Bombers launched at 0430 could not find the Japanese ships but at 0630 a PBY Catalina found the Japanese and radioed Midway “two Japanese battleships streaming oil.” The remaining 12 aircraft of VSMB-241 under command of Captain Marshall Tyler a mix of SBD Dauntless and SB2U Vindicators took off at 0700. His force attacked at 0808 scoring no hits. However, Marine Captain Richard Fleming, his Vindicator on fire dropped his bomb and then crashed his aircraft into Mikuma’s after turret. Sailors aboard Mogami were impressed, the American had sacrificed himself in a suicide attack worthy of the Samurai. The fire was sucked down air intakes into the starboard engine room with disastrous results. The Mikuma’s engineers were suffocated by the smoke and fumes and Mikuma was greatly reduced in speed.

The two ships limped northwest at 12 knots escorted by the destroyers and were unmolested through much of the day with the exception of an ineffective attack by the B-17s at 0830. The following morning the Dive Bombers of Enterprise and Hornet were at work and found the crippled Japanese ships. Waves over US Dive Bombers attacked the cruisers throughout the morning and into the afternoon. Mikuma was hit at least 5 times and secondary explosions of ammunition and torpedoes doomed the ship. Mogami was also heavily damaged but remained afloat while both destroyers received bomb damage. At sunset the tough cruiser rolled over to port and sank into the Pacific. Mogami whose damage control teams had performed miracles to keep their ship afloat helped the destroyers rescue survivors from Mikuma. Only 240 were rescued with 650 officers and sailors going down with the ship.

The action against the cruisers ended the combat operations at Midway. The Japanese ships were doomed by Yamamoto’s decision to try to salvage victory from defeat and the error of Mogami’s Navigator during the emergency turn when Kumano sighted Tambor. The only thing that kept the result from being total was the efficacy of Mogami’s damage control teams. Mogami was out of the war for 10 months following repairs and conversion to an Aircraft Cruiser in which her aft turrets were removed to increase the number of float plane scouts that the ship could carry. She rejoined the fleet in April 1943 and was sunk following the Battle of the Surigao Strait on 25 October 1944.

The Mogami and Mikuma proved to be tough ships to sink. Unprotected by friendly aircraft they fought hard against the unopposed American Dive Bombers. They suffered massive damage from 500 and 1000 pound bombs, both direct hits and near misses. Mogami was saved by the skill of her damage control teams and the foresight of her Damage Control Officer to jettison her torpedoes so that they did not explode and compound the damage wrought by the American bombs.

Epilogue

At Midway a distinctly smaller force defeated a vastly superior fleet in terms of experience, training and equipment. At the very moment that it appeared to the Japanese that they would advance to victory their vision disappeared. In a span of less than 5 minutes what looked like the certain defeat of the US Navy became one of the most incredible and even miraculous victories in the history of Naval warfare. In those 5 minutes history was changed in a breathtaking way. While the war would drag on and the Japanese still inflict painful losses and defeats on the US Navy in the waters around Guadalcanal the tide had turned and the Japanese lost the initiative in the Pacific never to regain it.

The Japanese government hid the defeat from the Japanese people instead proclaiming a great victory. The American government could not fully publicize the victory for fear of revealing the intelligence that led to the ability of the US Navy to be at the right place at the right time and defeat the Imperial Navy.

The American victory at Midway changed the course of the war in the Pacific. The Battle of Midway established the aircraft carrier and the fast carrier task force as the dominant force in naval warfare which some would argue it still remains. Finally those five minutes ushered in an era of US Navy dominance of the high seas which at least as of yet has not ended as the successors to the Enterprise, Hornet and Yorktown ply the oceans of the world and the descendants of those valiant carrier air groups ensure air superiority over battlefields around the world today.

The Target: Betio Island at Tarawa Atoll

The Target: Betio Island at Tarawa Atoll Japanese Emplacing 8″ Vickers Gun

Japanese Emplacing 8″ Vickers Gun Japanese conducting Live Fire Range prior to the Assault

Japanese conducting Live Fire Range prior to the Assault Admiral Shibasaki boasted that it would take a million men a thousand years to take Betio

Admiral Shibasaki boasted that it would take a million men a thousand years to take Betio Japanese Conducting Gunnery Exercises

Japanese Conducting Gunnery Exercises LVT Amphibious Tractor

LVT Amphibious Tractor 8 Inch Gun Emplacement

8 Inch Gun Emplacement Going Ashore

Going Ashore Navy LCT Sinking after Being Hit By Japanese Fire

Navy LCT Sinking after Being Hit By Japanese Fire Marines Wading Ashore

Marines Wading Ashore Colonel Shoup Directing Operations on Tarawa

Colonel Shoup Directing Operations on Tarawa Close Combat on Betio

Close Combat on Betio Wounded Marines Being Evacuated by Rubber Raft

Wounded Marines Being Evacuated by Rubber Raft Marines Advancing

Marines Advancing Wrecked LVY’s and Bodies on the Beach: The Marines Released Photos to Get the Public to Understand the Cost of the Battle

Wrecked LVY’s and Bodies on the Beach: The Marines Released Photos to Get the Public to Understand the Cost of the Battle One of the 17 Japanese Who Survived the Battle being Interrogated by Marines, only one Chief Warrant Officer Ota was an Officer

One of the 17 Japanese Who Survived the Battle being Interrogated by Marines, only one Chief Warrant Officer Ota was an Officer Lieutenant General Holland Smith and Major General Julian Smith on Betio

Lieutenant General Holland Smith and Major General Julian Smith on Betio Colonel Shoup After the Battle

Colonel Shoup After the Battle