This is an alternative history of how the Germans might have avoided the disaster at Kursk. It looks at what might have happened if an actual assassination attempt on Hitler had succeeded in March 1943 and how Manstein might have been able to execute the “backhand” strategy that he favored using a mobile defense. This is predicated by Hitler’s death, based on Hitler’s actions and control of operational decisions Manstein would never have been allowed the freedom to conduct operations in this manner. In eliminating Hitler I have also included personnel changes and the overall strategy for the German High Command, and the probable response of Stalin to Hitler’s death had it occurred in the spring of 1943. I have tried to be faithful to known historical opinions and actions of the participants and likely reactions to such a situation although one cannot predict precisely what people would have done. Thus I have documented the article with footnotes as if it were an actual history. It would have been interesting to be able to lengthen this and included sections on tactical actions based on memoirs of German and Russian soldiers. I wrote it as at the behest of one of my Master’s Degree Professors and first published it in August of 2009 on this site under the title of Operation “Dachs” My First Foray into the Genre “Alternative History.” I believe that history is history and this despite what the term “alternative history” implies is fiction. Though it is based on my belief of how German leaders might have reacted in the spring of 1943 and references actual events that I have altered for the sake of the story it is not history. But one has to wonder what would have happened had the plot to kill Hitler by blowing up his aircraft on its return to Germany from a conference with the commanders of Army Group Center succeeded.

Background: The Strategic Situation Spring 1943

In April 1943 the German High Command faced a decision on which the fate of Nazi Germany would hinge, but for the first time in the war it was not under the thumb of Adolf Hitler. Following Manstein’s counter-stroke following the Stalingrad disaster there was considerable pressure to follow up with that success with a continued offensive. Manstein himself had proposed this but Field Marshal Von Kluge refused to agree to an immediate offensive because he felt his troops needed rest and refitting.

Hitler’s Fw-200 “Condor” before its fatal flight

Hitler’s Fw-200 “Condor” before its fatal flight

On March 13th Hitler flew out to meet with Von Kluge at Army Group Center HQ at Smolensk. On the flight back Hitler’s FW-200 was racked by an explosion crash landing near Minsk, taken down by a bomb planted on the plane by Colonel Henning Von Trescow of Kluge’s staff.[i] While Hitler survived, he remained in critical condition, barely alive at a SS hospital until his death on 20 April 1943, his 54th birthday. The crash landing was reported by the escorting ME-109s of JG-53, and a Alarm Company from a Security Division at Minsk rescued Hitler but were driven off the crash site by a large force of Soviet Partisans who destroyed the aircraft and any evidence to the cause which the escorting fighters attributed to mechanical problems.

There were no other survivors. Von Kluge, expecting to be implicated the Fuhrer’s death committed suicide after visiting troops on the front line, and was succeeded at Army Group Center by Field Marshal Model the commander of 9th Army. The other conspirators were frozen into inaction when Hitler survived the crash and made no attempt to take over the government, realizing that “our plans for seizing power in Berlin and other large cities were still not adequate to the task.”[ii] In the absence of Hitler Reichsmarschall Goering, Hitler’s designated successor, took action to secure his power and using contacts in the GESTAPO accused Himmler of treason for making contact with Neutral intermediaries in Sweden[iii] and replaced him with SS General Kurt Wolfe, and reappointed Rudolf Diels, the former head of the GESTAPO when it was still under his control[iv], to head it again. Himmler attempted to flee and was caught near Luneburg when he committed suicide with a cyanide capsule before he could be interrogated. Other potential rivals were eliminated; Martin Bormann, who Goering hated, was arrested on charges of exceeding his authority, embezzlement, and harming the war effort and was executed.[v] Joseph Goebbels swore his loyalty to Goering even before Hitler’s death. He and Albert Speer were directed to arrange the state funeral for the late Fuhrer. Berlin Radio announced the Fuhrer’s death on the 21 April, Hitler’s body was prepared and lay in state at the Chancellery. A period of mourning was declared 21 April to 1 May on which the State Funeral took place. On 2 May Goering announced that Field Marshal Von Rundstedt was the new Chief of OKW and would coordinate strategy on all fronts. The next day Goering called together a meeting of the heads of OKH, OKW, the Inspector General of Panzer Troops, and the commanders of the Eastern Front Army Groups, Western Europe and Africa as well as Reichsfuhrer Karl Wolff, Admiral Donitz and Field Marshal Von Richthofen[vi] representing the Luftwaffe to decide on a course of action for the summer. It was the first time that all had been called together to discuss the overall situation since Barbarossa began in 1941, and the first true attempt to formulate a grand strategy during the war.

Options and Decision: The Zossen Conference 3 May 1943[vii]

Goering meeting Diplomats following Hitler’s State Funeral

Herman Goering looked up from the maps spread out on the conference table. He looked surprisingly fit, somehow between the crash of Hitler’s aircraft and his death he had pulled himself together and out of his drug induced malaise. It was as if he again had a purpose. Field Marshal Von Rundstedt now Chief of OKW following Goering’s relief of Field Marshal Keitel, and General Jodl had just finished briefing the situation in western and southern Europe, following briefings by Colonel General Zeitzler of OKH, the Inspector General of Armored Troops, General Guderian and Field Marshal Von Manstein of Army Group South. Albert Speer briefed tank and aircraft production numbers while the Chief of the Army personnel office noted the requirement for 800,000 replacements “but even the most ruthless call-up was able to produce only 400,000.”[viii] Looking from the table he spoke: “Gentlemen, the situation is critical and I have to admit that I have thought so for a number of months but have been unable to speak out. Our political situation is perilous, the Italians are ready to abandon our cause. Our forces in North Africa will soon be unable to hold out as our Italian friends have let us down again.[ix] I expect that if Jodl and Kesselring are right about Allied intentions that we will have our hands full in the west shortly. Kesselring and Arnim, you need to evacuate as many German soldiers from Africa as possible,[x] use all air and naval forces that you can, I know it will be difficult, especially with the heavy losses we have taken in transport aircraft and the pathetic Italian Navy.” Goering paused, his gaze passing around the room. “In the west we need to assume that the Allies will invade and the ‘very real danger that the enemy may turn against Brittany and Normandy,’ Field Marshal Rommel will take command of OB West to build up the Atlantic Wall in these sectors.”[xi] “Zeitzler, Manstein, we need to shore up the eastern front.”

“Herr Reichsmarschall, the Fuhrer had approved the plan called ZITADELLE, to attack the Russians here in the Kursk salient.” responded Zeitzler.[xii] “We should be ready to begin the offensive this month.” Goering raised his hand stopping Zeitzler. “I know, but I have considered that plan and I cannot support it. Richthofen briefed me on it prior to the Fuhrer’s death and general, we must have another plan, and an attack on Kursk is so obvious the Russians will be ready to meet it. I have considered what the General Guderian and Minister Speer said regarding tank production and the state of the Panzer arm. I cannot approve Zitadelle, but we must find a way to deal the Russians a defeat without squandering our strength attacking such an obvious target. Model too is dubious of the prospects; he believes that the Russians know our intentions and has requested a delay to strengthen his forces.”[xiii] “Reichsmarshall.” chimed in Jodl. “You are correct, the premature commitment of central reserves in such an offensive will not help our cause, in fact only local success is what can be expected from Zitadelle.”[xiv]

Colonel General Heinz Guderian

Colonel General Heinz Guderian

“But Reichsmarshall, we must recapture the initiative in the east, we must take the offensive!” retorted Zeitzler. “Our new units of Panthers and Tigers will give us a decisive technical advantage.”[xv] Guderian now joined in. “But the Panthers still have many technical problems, it would be better to wait until they are worked out before we commit them to a major offensive, and besides, how many people do you think even know where Kursk is?”[xvi]

“Zeitzler, I appreciate your zeal.” Interrupted Goering, “But Jodl and Guderian are correct, even a successful attack at Kursk will not alter the strategic situation. We must work to stave off defeat. Manstein has a plan that may help, there is some risk, but I see no other way. An offensive at Kursk would require tanks and aircraft that must be used to combat the Allied bombing of the Reich and to safeguard withdraw of our units from Africa, it would force us to commit everything with little gain.” Goering paused and said to Manstein, “Go ahead Manstein.”

“Reichsmarshall, Gentlemen. Our situation in the east is not hopeless, in March I felt that an immediate offensive would succeed in pinching off the Kursk bulge, but I think now that the moment of opportunity has passed for such an attack. Instead we should fight a defensive battle of maneuver as called for byTruppenführung that we have developed from the days of the Reichswehr. We should build up our forces; give ground where we can, and when we have the chance strike the enemy on the backhand, as we did at Kharkov.”[xvii]

Zeitzler jumped in. “But how can we do that? If we don’t strike now while we have the opportunity the Russians will grow stronger, and how can we know where they will strike?”[xviii]

“General Zeitzler, the Russians are already building up heavy armored forces in the area of Kursk, and diverting forces from other sectors of the front to that area. The south offers them the best opportunity to finish what they started in the winter. They will come and it will be in the south, they will want Kharkov and they will again attempt to envelop our forces in the south. If they succeed they will follow up and rapidly move into the Balkans, Romania and Hungary will turn on us and it will be a disaster, we cannot afford that.” Manstein looked up, Jodl nodded and Model said “Once that is done they will push to Kiev and Poland.” Goering interjected “Thank you Model, you are right, Field Marshal Manstein; please go on with your plan.”

Field Marshal Erich Von Manstein at the Front

Motioning to the map Manstein continued. “We will concentrate the majority of our Panzer forces here, just west of Kharkov and another group here west of Orel. We will also build fall back positions for our infantry forces here along the Dnieper. We should be ready to withdraw from the Crimea should the need arise, we cannot afford another encirclement. When the Russians attack we will give ground, even Kharkov if needed. Our infantry divisions will fight a delaying action supported by Jagdpanzer and Sturmgeschutzen, the Luftwaffe will need to give us good close air support from Stukas and as the Russians outrun their supply depots and their offensive loses momentum we will attack, like a badger defending itself. Our Panzers will cut off their spearheads west of Kharkov while we bleed them dry in the north; we will then roll them up, stabilize the line and prepare for the winter.” Manstein sounded confident; those in the room began to sense that his plan could work. Rundstedt spoke up: “That will give us the chance to transfer forces to other fronts and, maybe, since Hitler is dead there might be a chance for Reichsmarschall to negotiate a settlement,[xix] otherwise gentlemen the Allies will destroy our cities from the air and grind our armies down until we have no recourse but surrender.”

“Right” added Goering, making eye contact with each man in the room. “We must have success in the defense, we must buy time and we must work to end this war before Germany is destroyed. ‘We will have reason to be glad if Germany can keep the boundaries of 1933 after the war.”[xx] He paused and said “General Zeitzler, you are relieved of your duties at OKH, General Guderian, you are now the Chief of OKH.[xxi] Manstein, you will command the East, General Hoth will take your Army Group. You will work with Guderian and Model to flesh out this plan. We must get the Panther, Tiger and Ferdinand units operational as soon as possible. I believe that the Russians will attack by June. Richthofen, I need you to look to the Luftwaffe. We have not had a good year and we have to succeed in defending the Reich from Allied bombers and provide support to the ground forces. Of course flak needs to be built up. The Luftwaffe Field Divisions with the exception of the Fallschirmjaeger and Herman Goering Panzer Division need to be transferred to Army control.” He looked at Speer: “Herr Speer, the Fuhrer entrusted you with our war production program, you must increase production of tanks and aircraft. Speed the production of the ME-262 and cancel all programs that take away from the panzers, fighters and ground support aircraft that we need now.” He put his hands on his hips and took a deep breathe. He looked at Wolfe, Himmler’s successor. Wolff, the Reich needs the Waffen SS, the Panzer troops are exceptional, but I want all Waffen SS Formations, with including the Panzers turned over to Army control, we cannot keep dividing our resources. With the personnel from the Luftwaffe Field Divisions we should be able to provide the Army with excellent troops to rebuild experienced formations.” Goering looked around the room; “Are there any questions Gentlemen?” Putting his arm across Manstein’s soldier and said: “I think that Badger is a fitting name for your plan. Our little Dachs will tear them to pieces.” Later, Goering met with Foreign Ministry officials emphasizing the need to strengthen German Allies and seek peace with the west. He “admitted that he was worried about the future. ‘It’s not quite clear to me how we are going to end this war.’”[xxii] Those present could not believe how Goering had conducted himself, and all left the meeting thinking that it might be possible to stave off defeat. It was an incredible performance. After Hitler’s crash he had secretly undergone a “systematic withdraw cure which had ended his drug addiction.”[xxiii] The change was marked.

STAVKA Headquarters Moscow: 7 May 1943

Josef Stalin was ecstatic. His agents reported that Hitler was dead even before the announcement from Berlin. Partisans had confirmed that it was Hitler’s aircraft that they found and recovered some of Hitler’s personal belongings, including his cap, which they presented to Stalin. Intelligence reported that Goering had taken power, and Stalin was sure that his position was weak and many believed that Goering, was not up to the task, and that a renewed offensive could bring down the Nazi regime. Now was the time to bring the Nazi terror to an end and Stalin called his key leaders together. While Stalin wanted an immediate offensive his generals wanted to wait just in case the Germans attacked Kursk. “Zhukov, Vasilevsky, and various General Staff officers urged caution and recommended that the Red Army remain on the defensive until the Germans expended their offensive strength.”[xxiv] Stalin supported by commanders, like Vatutin, “argued for a resumption of offensive action in early summer to preempt German action and regain the momentum lost in March 1943.”[xxv] In the end a compromise was reached and despite the temporary defensive stand “Russian strategic planning in the summer of 1943 was inherently offensive in nature.”[xxvi] The new offensive would be launched on 15 June if the Germans had not attacked before. It would be named Operation Kutuzov[xxvii] and be aimed at the Orel salient and Kharkov. The northern prong under Rokossovsky’s Central Front would destroy the Germans around Orel and drive west while Vatutin’s Voronezh and Konev’s Steppe Front would take Kharkov and drive toward the Dnieper.[xxviii] The Southwest Front and South Fronts would attack and destroy the German forces along the Mius, the goal: “collapse of the German defenses and an advance to the line of the Dnieper River from Smolensk in the north southward to the Black Sea.”[xxix]

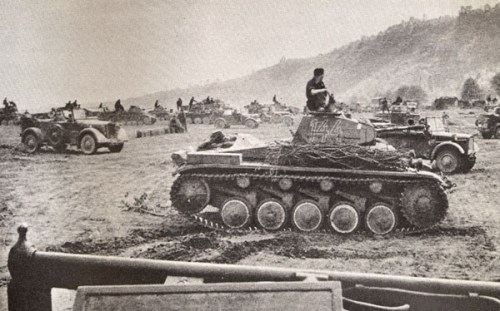

Sturmgeschutzen and SdKfw 251 APCs moving into position

Manstein met with Model, Hoth and Guderian to develop DACHS. They had to play for time and deceive the Russians as to their true intent so they could build up their forces. Deception operations were mounted on both sides of the Kursk bulge to give the impression of attack preparations. 1st Panzer Army and Army Detachment Kempf were to launch a diversion called Operations HABICHT and PANTHER southeast of Kursk “designed to push the Soviets back from the industrial area of the Donets River.”[xxx] The defensive plan called for the infantry supported by tank destroyers, assault guns the heavy Ferdinands as well as mobile Pioneer units to conduct a withdraw to delay and disrupt the Russian attack. Bridges were prepared for demolition, defensive positions constructed at choke points which would be defended and then abandoned when no longer defensible, and minefields laid to slow the Russian advance. This was critical for 9th Army now commanded by General Henrici in the Orel salient north of Kursk. Henrici, a defensive master constructed a series of defensive belts to allow his army to withdraw from the bulge without being cut off and inflict heavy casualties on the Russians through skillful deployment of anti-tank weapons, especially self propelled guns.[xxxi] In the south 4th Panzer Army, now commanded by SS General Paul Hausser[xxxii] and Army detachment Kempf made preparations to allow the Russians to advance past Kharkov using the same defend and delay tactics and then counterattack. As the armies prepared, Speer and Guderian’s efforts to rebuild the Panzer force were bearing fruit. By 15 May the first brigade of Panther tanks was activated and began training west of Kharkov.[xxxiii] Two battalions of Ferdinands, one for 9thArmy and one for 4th Panzer Army were activated.[xxxiv] Sturmgeschutzbattalions were assigned to each infantry corps. Panzer divisions built up so that all had an average of 130 tanks, with the SS Divisions and Gross Deutschland receiving more. Tiger battalions were assigned to each Panzer Corps.

The Summer Campaign

German Infantry

On 1 June Operations PANTHER and HABICHT hit the unfortunate Soviet 6thArmy, which had been victimized by Manstein’s counter-stroke in March. III Panzer Corps of Army Detachment Kempf supported by Corps Raus (IX Corps) linked up with 1st Panzer Army at Kupiansk on 3 June. The Russian counterattacked with 8th Guards Army and the 2nd and 23rd Tank Corps. The battle of Kupiansk resulted in the destruction of 6th Army and the 23rd Tank Corps which was surprised by the 503rd Panzer Detachment’s Tigers. 2nd Tank Corps received a similar mauling at the hands of the 6th Panzer Division. On 9 June the Germans returned to their start positions.

Soviet Tanks and AT Guns at Kupiansk

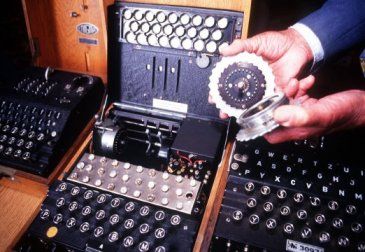

The attack at Kupiansk surprised STAVKA which had been deceived by the build up of Panzers around the Kursk salient. Stalin continued to hound his generals to begin Kutuzov on time, but the generals were “chastened” by the defeat at Kupiansk and “earlier experiences”[xxxv] and wanted to delay. Stalin forced them to begin Kutuzov on 22 June, the 2nd Anniversary of Barbarossa. Manstein and his Eastern Front commanders held their breath. Teams of Brandenburger commandos operating in the Soviet rear and Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft reported Russian units moving to advanced positions to the north and south of Kursk. Vatutin commanding the Voronezh Front was ambushed and killed by a Brandenburger detachment supporting Ukrainian irregulars[xxxvi] as he returned from visiting 69th Army near Prokhorovka station on 19 June and was replaced by Lieutenant General Katukov of 1st Tank Army. Katukov “was one of the Red Army’s most accomplished and experienced armor officers.”[xxxvii]

Manstein with Tigers

In the north Rokossovsky’s Central Front and Popov’s Bryansk Front supported by 11th Guards Army[xxxviii] began concentric attacks on the German 9th and 2nd Panzer Armies and ran into Henrici’s labyrinth on 22 June. They hit the first line they found it empty, the Germans having repaired to secondary positions,[xxxix] German 88’s and self propelled guns took a heavy toll on the tanks of 2nd Tank Army. The 3rd Tank Army under General Rybalko’s army committed after the initial assault “attempted a fresh penetration instead of exploiting the earlier efforts of the 3rd and 63rd Armies… Rybalko’s force included 698 serviceable tanks…but lacked the artillery and engineers for such a deliberate assault.”[xl] Popov telephoned Stalin at noon on 25 June “to report that Rybalko was practically stalled and suffering heavy losses in tanks.”[xli]The Germans committed the 5th and 8th Panzer divisions[xlii] against 3rd Tank Army. The fresh Panzers inflicted painful losses on Rybalko. On 27 June Stalin called to complain about the handling of the army, demanding a direct assault.[xliii] The battle turned into a “grinding battle of armored attrition.”[xliv] After “a few bloody days bereft of any success, Rybalko’s tank formations had to be pulled out of the line into reserve.”[xlv] The “battle for the Orel salient ended three weeks later with a German defensive victory, as Army Group Center extricated its two armies from the box prepared for them while inflicting heavy casualties on three Soviet Fronts.”[xlvi] The Soviets lost over 629,000 men and 3,500 tanks.[xlvii] In comparison German losses were light and by falling back they shortened their line freeing units for other operations. Stalin had Orel but failed to destroy the Germans and lost heavily in the attempt.

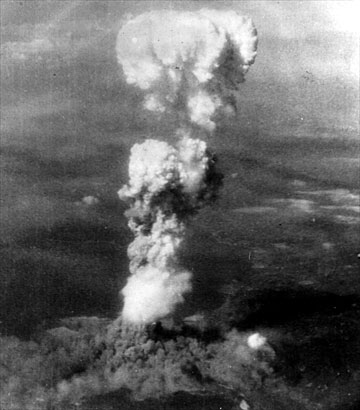

Panzer IV’s engaging Soviet forces

Panzer IV’s engaging Soviet forces

In the south Konev’s Steppe and Katukov’s Voronezh Fronts prepared their assault on Kharkov. They attempted to deceive the Germans by simulating the massing of a “notional tank and combined-arms army” in the western side of the Kursk bulge.[xlviii] The deception was unsuccessful as reconnaissance by Luftwaffe aircraft and Brandenburgers failed to uncover any troop concentrations and Russian deserters, talked of a strike at Kharkov. The offensive “Rumiantsev” was opened by the 5th and 6th Guards armies supported by 53rd and 69th Armies on 21 June; a day later 7th Guards Army jumped off, two additional armies supported the west flank of the offensive.[xlix] The Russians in the two fronts began the operation with 980,000 men and 2,500 tanks.[l] Opposing them were 4th Panzer Army and Army Detachment Kempf’s 350,000 men and 1,750 tanks and assault guns including 100 Tigers and 192 Panthers.[li]

T-34 towing disabled T-34 near Orel

STAVKA “chose to strike the strongest portion of Hoth’s defense head-on, to engage and defeat the German force and avoid the problems of flank threats.”[lii] Unfortunately they complicated the attack by focusing it at “precisely the boundary between the Voronezh and Steppe Fronts, causing increased coordination problems from the start of the operation.”[liii] The Germans used Ferdinands, Jagdpanzers and Sturmgeschutz in a mobile defensive role, as infantry fought delaying actions as they withdrew to successive defensive lines, inflicting brutal losses on the Russians. Aided by massive artillery preparation the Russians broke through the weakened Army Detachment Kempf near Belgorad[liv] taking the city on 24 June. Corps Raus’ 167th Infantry Division was taken on its exposed left flank forcing Raus to “fight a delaying action…until the withdraw reached Kharkov.” [lv] The Germans reacted to the threat by committing the “veteran 5th SS Panzer Grenadier Division Wiking” to reinforce Army Detachment Kempf.[lvi] Despite the success “the German defenses proved so tenacious that the leading brigades of the two tank armies had to enter the fray.”[lvii]

Destroyed column of T-34s

Destroyed column of T-34s

As the Russians advanced the German fell back. Hoth directed Hausser to wait before counterattacking with XLVIII Panzer Corps and II SS Panzer Corps. Katukov pushed the 1st and 5th Tank Armies into the hole in the German lines and moved toward Kharkov which was liberated by the 89th and 183rd Guards Divisions[lviii] on 2 July. The liberation of Kharkov and Belgorad while exhilarating had cost Katukov over 250,000 casualties. Skillful employment of mobile defense and local counterattacks by mixed Panzer battlegroups, such as one by Grossdeutschland on the flank of 5th Tank Army caused panic and some units withdrew “leaving behind masses of equipment of every description.”[lix]The tank armies had lost upwards of 50 percent of their tanks, infantry divisions were now down to half strength, some down to 3000 men.[lx] Yet the Soviets attempted to drive south to trap the Germans. They were hit by XLVIII Panzer Corps and II SS Panzer Corps, both of which had seen little action thanks to Hoth’s conservation of strength. XLVIII Panzer Corps hit the 1st Tank Army at the “key road junction of Bogodukhov, 30 kilometers northwest” of Kharkov “severely mauling the leading three brigades”[lxi] forcing 1st Tank Army to withdraw towards Kursk. 5th Tank army moved to support but was taken in the flank by II SS Panzer Corps. The SS Corps encircled the remainder of 5th Tank Army. Hunted by the SS on the open steppe the survivors slipped through gaps in the encirclement but both armies were ravaged. By 15 June 1st Tank Army was down to 120 tanks and 5th Tank Army had “50 of its original 503 tanks and self-propelled guns serviceable.”[lxii] XLVII Panzer Corps took Kharkov on 18 July.

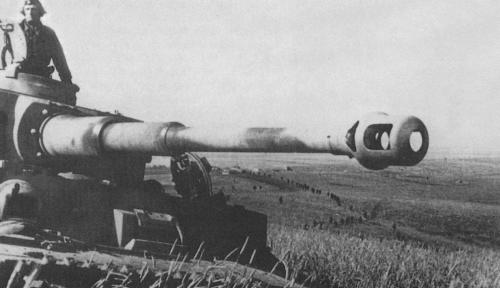

SS Panzer Grenadiers and Panzertrüppen Tigers of 3rd SS Panzer Division prepping for battle

The victory paid dividends for the Germans. The Front held and the Russians had taken nearly a million casualties and lost almost 6000 tanks and self-propelled guns. Three Tank Armies had been smashed, 5th Tank Army would not be fit for field duty for two months.[lxiii] 3rd Tank Army earned a Guards designation but was withdrawn from combat.[lxiv] 6th Army, victimized by PANTHER was destroyed while the 5th, 6th and 7th Guards Armies were shattered. Additionally, the Germans decimated two independent tank corps. Stalin reacted by halting operations, cancelling follow on offensives and rebuilding the Red Army’s tank armies and mechanized forces. He realized that his Generals had been right in not wanting to undertake offensive operations until the Germans had been weakened, but the German insistence on not going on the offensive caused him to ignore their arguments. He decided to wait until winter to launch his next offensive, but that offensive would never be launched as by the time he was ready the war was over.

German Tank Commander as Panzers mop up

The elimination of the Russian threat enabled Italy to be reinforced as well as the reinforcement of the Atlantic Wall. The Salerno landings were a disaster, the Allies driven into the sea by Panzer Divisions released from the Eastern Front. The disasters at Salerno and the Russian debacle brought overwhelming domestic political pressure on Roosevelt and Churchill to end the war. Clandestine talks began in Switzerland between Avery Dulles and Karl Wolff[lxv] while Walter Schellenberg met with Count Bernadotte.[lxvi] Despite the previous demand for unconditional surrender the Allies decided to negotiate with the new German leadership might end the war in Europe. Goering surrendered power to General Beck and gave himself and other accused war criminals up to the Allies. Beck took power, withdrew to 1939 borders, dismantled the death camps and disbanded the Nazi Party, and its police apparatus.[lxvii] Peace came to Europe on 9 November 1943, 25 years after Kaiser Wilhelm’s abdicated his throne.

Goering Surrenders to the Allies

[i] Clark, Alan. Barbarossa: The Russian German Conflict, 1941-45. Harper Collins Publishers, New York, NY 1965. Pp.307-311. There was an attempt on Hitler’s life on his return from Kluge’s headquarters. Only the bomb did not go off, all components had worked but the detonator did not fire. Clark notes that “the Devil’s hand had protected Hitler.” (p.311)

[ii] Galante, Pierre. Operation Valkyrie: The German Generals’ Plot Against Hitler. Translated by Mark Howson and Cary Ryan. Harper and Row Publishers, New York, NY 1981. Originally published as Hitler est il Mort? Librairie Plon-Paris-Match, France. 1981. p.167

[iii] Padfield, Peter. Himmler. MJF Books, New York. 1990. p.474. Himmler had a number of contacts and intermediaries who he used to attempt contact with the Allies as early as 1943.

[iv] Höhne, Heinze. The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS. Translated by Richard Barry. Penguin Books, New York and London, 2000. First English edition published by Martin Secker and Warburg Ltd. London 1969. Originally published as Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf, Verlag Der Spiegel, Hamburg 1966. Diels remained an ally of Goering even marrying his sister in 1943.

[v] Von Lang, Jochen. The Secretary: Martin Bormann: The Man Who Manipulated Hitler. Translated by Christa Armstrong and Peter White. Random House Inc. 1979. Originally published as Der Secretär. Deutsche-Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart. 1977 p.9. At his trial Goering remarked to other defendants. “If Hitler had died sooner, I as his successor would not have had to worry about Bormann. He would have been killed by his own staff even before I could have given the order to bump him off.”

[vi] Irving, David. Göring: A Biography. William Morrow and Company, New York, NY 1989. Richthofen had succeeded Jeschonnek in March when Goering relieved him. Goering believed that Jeschonnek “was too pliable at the Wolf’s Lair.” Goering had actually considered this a number of times but postponed it several times. p.388

[vii] Guderian, Heinz. Panzer Leader. (abridged) Translated from the German by Constantine Fitzgibbon, Ballantine Books, New York 1957. pp.244 Hitler conducted a similar conference involving many of the same people in Munich.

[viii] Carell, Paul. Scorched Earth: The Russian German War 1943-1944. Translated by Ewald Osers, Ballantine Books, New York, NY 1971, published in arrangement with Little-Brown and Company. p. 336

[ix] Ibid. Irving. pp. 377-379.

[x] Ibid. Guderian. p.243

[xi] Ibid. Irving. p.378

[xii] Glantz, David M and House, Jonathan. The Battle of Kursk. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 1999. pp.21-25. Operations order 5 had been approved by Hitler on and issued by OKH on 13 March. It was followed by Operations Order 6 on 15 April.

[xiii] Ibid. Clark. p.324.

[xiv] Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-45. Translated by R.H. Berry, Presido Press, Novato CA, 1964. p.334 These objections of Jodl were from June, but indicate the feeling of Jodl for the Zitadelle as planned and when would have likely been his response in such a situation.

[xv]Glantz, David M. and House, Jonathan. When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 1995. p.157 Zeitzler had been a consistent advocate for Zitadelle since he heard Manstein’s initial proposal in March.

[xvi]Macksey, Kenneth. Guderian: Creator of the Blitzkrieg. Stein and Day Publishing, New York, NY 1975 p.206

[xvii] Ibid. Clark. p.322

[xviii] Ibid. Clark. p.323. Zeitzler made this argument with Jodl during a briefing in April 1943.

[xix] Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. A Touchstone Book published by Simon and Schuster, 1981, Copyright 1959 and 1960. p.1115. Hitler had told Keitel and Jodl that “When it comes to negotiating [for peace]…Goering can do much better than I. Goering is much better at those things.”

[xx] Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich. Collier Books, a Division of MacMillan Publishers, Inc. New York, NY 1970. p.245. From a conversation with Speer in late 1942.

[xxi] Ibid. Glantz and House. Clash of Titans. pp. 216-217. Hitler would replace Zeitzler with Guderian in June 1944.

[xxii] Ibid. Irving. p.379 From a conversation with State Secretary Ernst von Weizäcker 11 February 1943.

[xxiii] Ibid. Speer. p.512. The ending of the addiction took place at Nurnberg and Goering surprised many of his co-defendants with his “remarkable energy.”

[xxiv] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.28

[xxv] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.28.

[xxvi] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.264

[xxvii] Overy, Richard. Russia’s War: A History of the Soviet War Effort: 1941-1945. Penguin Books, New York NY and London, 1997. pp.211

[xxviii] Erickson, John. The Road to Berlin. Cassel Military Paperbacks, London, 2003. First Published by Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1983. p.76

[xxix] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.265

[xxx] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.23.

[xxxi] Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Quill Publishing, New York, NY. 1979. Copyright 1948 by B.H. Liddell-Hart. p.215 Henrici describes the methods that he used in 1944 as Commander of 1st Panzer Army and as Commander of Army Group Vistula during the defense of Berlin.

[xxxii] Hausser would actually command 7th Army in Normandy in 1944.

[xxxiii] Ibid. Glantz and House Kursk. p.53 This was the 10th Panzer Brigade assigned to XLVIII Panzer Corps. Additionally Clark notes production figures for Panthers from Speer that indicate that 324 Panthers would be available by 31 May. (Clark. p.325)

[xxxiv] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.52. At Kursk the two Ferdinand detachments were both assigned to 9th Army.

[xxxv] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.28.

[xxxvi] Ibid. Carell. p.510. Vatutin was killed by Ukrainian irregulars in April 1944.

[xxxvii] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.62

[xxxviii] Newton, Steven H. Hitler’s Commander: Field Marshal Walter Model, Hitler’s Favorite General. DeCapo Press, Cambridge MA 2005. p. 256

[xxxix] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. p.215.

[xl] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.236

[xli] Ibid. Erickson. p.113. At Kursk the call took place on 20 July when Rybalko was in this situation.

[xlii] Ibid. Newton. p.256

[xliii] Ibid. Erickson. p.114

[xliv] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.236

[xlv] Ibid. Erickson. p.114

[xlvi] Ibid. Newton. p.256

[xlvii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.345. The actual losses were 429,000 men and 2,500 tanks against a German force significantly weakened by Zitadelle. Had the Russians attacked the Germans rather than receiving the German attack first their losses in men and machines would have been far higher. I have reflected that in the alternative numbers.

[xlviii] Ibid. Glantz and House. When Titans Clashed. p.168 The Soviets did try this in their counter offensive following Zitadelle.

[xlix] Ibid. Glantz and House. When Titans Clashed. p.169

[l] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.344. Actual figures for beginning of offensive.

[li] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.338. Figures from beginning of Zitadelle.

[lii] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.244 The actual text reads “Manstein’s defense” not Hoth’s.

[liii] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.244

[liv] Von Mellenthin, F.W. Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the Second World War. Translated by H. Betzler, Ballantine Books, New York, NY, 1971. Originally Published University of Oklahoma Press, 1956. p.286

[lv] Raus, Erhard. Panzer Operations: The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus, 1941-1945. Compiled and Translated by Steven H Newton. Da Capo Press a member of the Perseus Book Group, Cambridge, MA 2003. p.214

[lvi] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.247

[lvii] Ibid. Glantz and House. When Titans Clashed. p.169

[lviii] Ibid. Erickson. p.121 These were the actual divisions that liberated Kharkov.

[lix] Ibid. Von Mellenthin . p.287

[lx] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.252

[lxi] Ibid. Glantz and House. When Titans Clashed. p.170

[lxii] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.252

[lxiii] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.252

[lxiv] Ibid. Glantz and House. Kursk. p.237

[lxv] Ibid. Hohne. p.572

[lxvi] Ibid. Hohne. p.570

[lxvii] Ibid. Galante. pp 69 and 207

Bibliography

Carell, Paul. Scorched Earth: The Russian German War 1943-1944. Translated by Ewald Osers, Ballantine Books, New York, NY 1971, published in arrangement with Little-Brown and Company

Clark, Alan. Barbarossa: The Russian German Conflict, 1941-45. Harper Collins Publishers, New York, NY 1965

Erickson, John. The Road to Berlin. Cassel Military Paperbacks, London, 2003. First Published by Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1983

Galante, Pierre. Operation Valkyrie: The German Generals’ Plot Against Hitler.Translated by Mark Howson and Cary Ryan. Harper and Row Publishers, New York, NY 1981. Originally published as Hitler est il Mort? Librairie Plon-Paris-Match, France. 1981.

Glantz, David M and House, Jonathan. The Battle of Kursk. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 1999.

Glantz, David M. and House, Jonathan. When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 1995

Guderian, Heinz. Panzer Leader. (abridged) Translated from the German by Constantine Fitzgibbon, Ballantine Books, New York 1957

Höhne, Heinze. The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS. Translated by Richard Barry. Penguin Books, New York and London, 2000. First English edition published by Martin Secker and Warburg Ltd. London 1969. Originally published as Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf, Verlag Der Spiegel, Hamburg 1966.

Irving, David. Göring: A Biography. William Morrow and Company, New York, NY 1989

Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Quill Publishing, New York, NY. 1979. Copyright 1948 by B.H. Liddell-Hart

Macksey, Kenneth. Guderian: Creator of the Blitzkrieg. Stein and Day Publishing, New York, NY

Newton, Steven H. Hitler’s Commander: Field Marshal Walter Model, Hitler’s Favorite General. DeCapo Press, Cambridge MA 2005

Overy, Richard. Russia’s War: A History of the Soviet War Effort: 1941-1945.Penguin Books, New York NY and London, 1997

Padfield, Peter. Himmler. MJF Books, New York. 1990

Raus, Erhard. Panzer Operations: The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus, 1941-1945. Compiled and Translated by Steven H Newton. Da Capo Press a member of the Perseus Book Group, Cambridge, MA 2003

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. A Touchstone Book published by Simon and Schuster, 1981, Copyright 1959 and 1960.

Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich. Collier Books, a Division of MacMillan Publishers, Inc. New York, NY 1970.

Von Lang, Jochen. The Secretary: Martin Bormann: The Man Who Manipulated Hitler. Translated by Christa Armstrong and Peter White. Random House Inc. 1979. Originally published as Der Secretär. Deutsche-Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart. 1977

Von Mellenthin, F.W. Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the Second World War. Translated by H. Betzler, Ballantine Books, New York, NY, 1971. Originally Published University of Oklahoma Press, 1956.

Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-45. Translated by R.H. Berry, Presido Press, Novato CA, 1964.

Patton with French Renault F1 Tank in WWI

Patton with French Renault F1 Tank in WWI US Ace Eddie Rickenbacker with French Supplied Nieuport 28

US Ace Eddie Rickenbacker with French Supplied Nieuport 28 French Troops in Afghanistan: The French, British and Canadians have the most Robust Rules of Engagement of Non US NATO Forces (Time Magazine Photo)

French Troops in Afghanistan: The French, British and Canadians have the most Robust Rules of Engagement of Non US NATO Forces (Time Magazine Photo) Conflicting War Aims: Hitler with Finland’s Field Marshal Von Mannerheim

Conflicting War Aims: Hitler with Finland’s Field Marshal Von Mannerheim Italian M 13-40 tanks were the mainstays of Italian Armored Units, Slow, Undergunned and Poorly Armored they were No Match for Soviet T-34s

Italian M 13-40 tanks were the mainstays of Italian Armored Units, Slow, Undergunned and Poorly Armored they were No Match for Soviet T-34s

Obsolete French Built Romanian R-35 Light Tank

Obsolete French Built Romanian R-35 Light Tank Romanian ME-109 E4, The Romanian Air Force Was One of the Axis Success Stories

Romanian ME-109 E4, The Romanian Air Force Was One of the Axis Success Stories

Manstein with Tiger I Tanks

Manstein with Tiger I Tanks The Soviets Reinforced and Fortified the Kursk Salient

The Soviets Reinforced and Fortified the Kursk Salient General Heinz Guderian, Inspector of Panzer Troops was one of Few Senior German Officers to Oppose ZITADELLE from the Beginning

General Heinz Guderian, Inspector of Panzer Troops was one of Few Senior German Officers to Oppose ZITADELLE from the Beginning Hitler Felt Regaining the Initiative in the East was Critical to Keeping his Allies in the War

Hitler Felt Regaining the Initiative in the East was Critical to Keeping his Allies in the War The New Tiger Tanks Were to Play a Critical Role in the Attack

The New Tiger Tanks Were to Play a Critical Role in the Attack Soviet Forces Expected the Attack and Were well Prepared to Meet it

Soviet Forces Expected the Attack and Were well Prepared to Meet it General Alfred Jodl at OKW Protested the Offensive Verbally and in Writing

General Alfred Jodl at OKW Protested the Offensive Verbally and in Writing Tigers Advancing

Tigers Advancing Panzers on the Advance

Panzers on the Advance T-34’s and Infantry

T-34’s and Infantry Destroyed Panzers

Destroyed Panzers Manstein planning at the front

Manstein planning at the front

Tiger Tanks assigned to 1st SS Panzer Division

Tiger Tanks assigned to 1st SS Panzer Division  Soviet formations advance

Soviet formations advance Panzers assembling to attack

Panzers assembling to attack SS Panzers in Kharkov

SS Panzers in Kharkov

Knocked Out T-34s

Knocked Out T-34s Panzer IV F

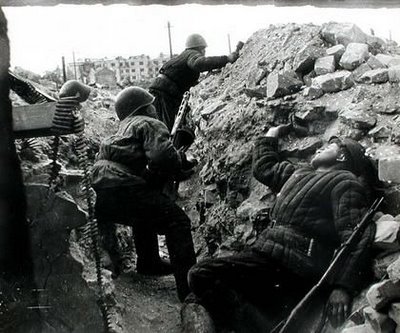

Panzer IV F German Soldier in Stalingrad

German Soldier in Stalingrad

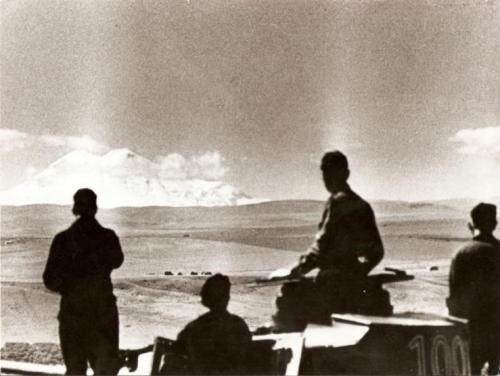

German Panzer Troops Look Upon the Caucasus Mountains

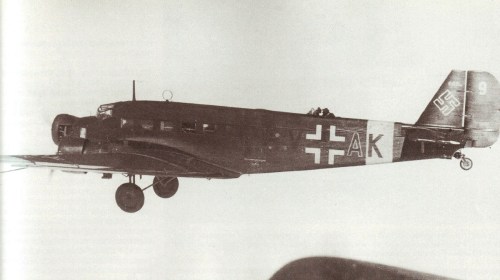

German Panzer Troops Look Upon the Caucasus Mountains JU-52: Despite Tremendous Bravery of Luftwaffe Pilots Goering Failed to Keep Stalingrad Supplied

JU-52: Despite Tremendous Bravery of Luftwaffe Pilots Goering Failed to Keep Stalingrad Supplied Soviet Armor on teh Offensive

Soviet Armor on teh Offensive T-34 in Stalingrad

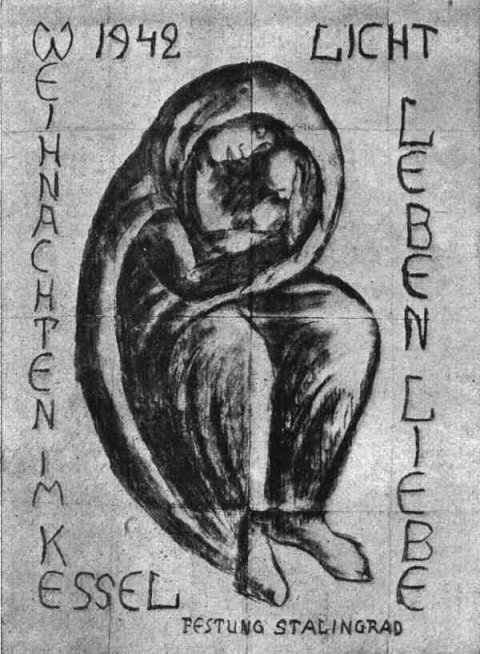

T-34 in Stalingrad The Madonna of Stalingrad

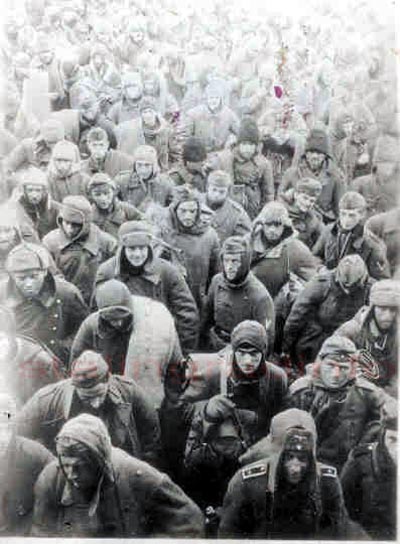

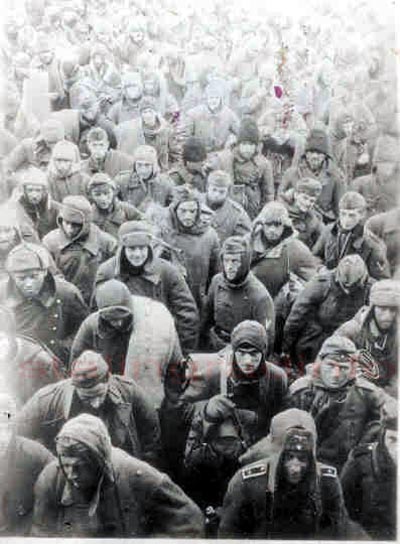

The Madonna of Stalingrad POWs: Only 5,000 of 90,000 POWs would return

POWs: Only 5,000 of 90,000 POWs would return