Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

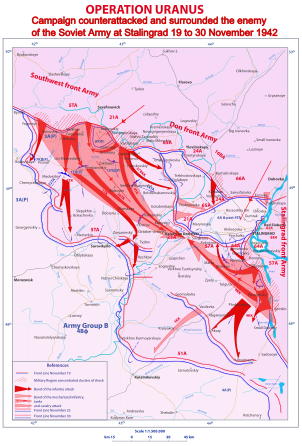

On November 19th 1942 the Soviet Red Army launched Operation Uranus against the weakly held flanks of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad. By 22nd 1942 the Commander of the German 6th Army radioed Berlin that the Red Army had surrounded his army, as well as portions of the 4th Panzer Army. But Operation Uranus was simply the beginning of an end which Hitler had embarked on June 22nd 1941 when he launched Operation Barbarossa. It would end in May of 1945 when Berlin surrendered following the Soviet offensive across the Oder-Neisse rivers and defensive lines, known by the Soviets as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation. There is a direct line between the former and the latter, and Operation Uranus was the beginning of the end of Nazi Germany, but the line from Barbarossa to Berlin is a line that is so connected that the atrocities, war crimes, and crimes of both sides, against humanity in between cannot be disconnected from each other.

This is certainly no moral equivalence in my argument. The Nazis under Hitler were the aggressors. They defined the character of the war of aggression on which they embarked, despite the crimes of Stalin before and after the war.

Tonight I am posting what was a paper for one of my Masters degree classes dealing with the German 1942 summer offensive, Operation Blau, which ended when the Red Army began its counter-offensive on November 18th 1942. The German offensive ended in a disastrous defeat at Stalingrad which could have been even worse had it not been for the superb improvisation of Field Marshal Erich Von Manstein who extricated the rest of Army Group South from the Caucasus and stuck a counterblow that halted the Soviet advance.

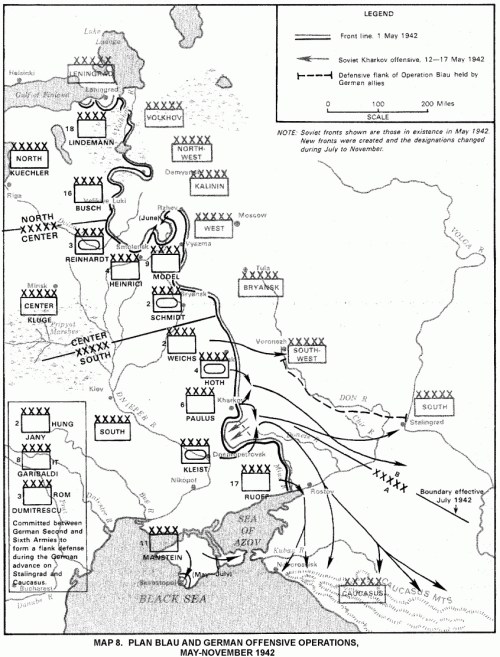

German and Soviet Plans

Following the Soviet winter offensive and the near disaster in front of Moscow the German High Command was faced with the strategic decision of what to do in the 1942 campaign. Several options were considered and it was decided to seize the Caucasus oilfields and in the process capture or neutralize the city of Stalingrad on the Volga. River.

However, the German High Command was divided on the actual objectives of the campaign. The OKH (Oberkommando Des Heeres) under the guidance of Army Chief of Staff General Franz Halder, which was in charge of the Eastern Front, assumed that Stalingrad was the objective of the campaign. They believed that the advance into the Caucasus was to be a blocking effort.[i] On the other hand, Hitler and his OKW (Oberkommando Der Wehrmacht) envisioned that Army Group South would capture the Caucasus oil fields and capture or neutralize Stalingrad to secure the left flank.[ii]

Both the OKH and OKW considered Stalingrad significant but OKW “initially regarded it as a weigh station en route to the Caucasus oil fields.”[iii] The conflict between OKH and OKW apparent in the ambiguity of Directive No. 41. The directive “included the ‘seizure of the oil region of the Caucasus’ in the preamble concerning the general aim of the campaign, yet made no mention of this in the main plan of operations.”[iv]

At the planning conference held at Army Group South in early June “Hitler hardly mentioned Stalingrad. As far as his Generals were concerned it was little more than a name on the map. Hitler’s obsession was with the oil fields of the Caucasus.”[v] Manstein noted that “Hitler’s strategic objectives were governed chiefly by the needs of his war economy….”[vi] Anthony Beevor notes that at this stage of planning “the only interest in Stalingrad was to eliminate the armaments factories there and secure a position on the Volga. The capture of the city was not considered necessary.”[vii] German planners “expected that the Soviets would again accept decisive battle to defend these regions.”[viii]

Knocked out T-34 Tanks

In Moscow Stalin and his Generals attempted to guess the direction of the impending German offensive. “Stalin was convinced that Moscow remained the principle German objective…Most of the Red Army’s strategic reserves…were therefore held in the Moscow region.”[ix]

With this in mind the Red Army attempted to disrupt the German offensive and to attempt to recover the key city of Kharkov. The Red Army launched three offensives against the Germans under the direction of Stavka. The largest of these, an attempt to take Kharkov was defeated between 12-22 May with the loss of most of the armor in southern Russia. This compounded by an equally disastrous defeat of Red Army forces in Crimea by Von Manstein’s 11th Army. The heavy losses meant that the Red Army would face the German offensive in a severely weakened condition.[x]

Operation Blau

The German offensive began on 28 June under the command of Field Marshal Fedor von Bock. Von Bock’s command included two separate army groups, Army Group B under Field Marshal Maximillian Von Weichs. Army Group B was comprised of 2nd Army, 6th Army, and the 4th Panzer Army. It also had three allied armies, the Italian 8th Army, the 2nd Hungarian, and 4th Romanian. These forces operated in the northern part of the operational area. Army Group A, under command of Field Marshal Wilhelm List was comprised of The 17th Army, 11th Army, and 1st Panzer Army.[xi] One allied Army, the Romanian 3rd Army was attached to it.

The allied armies which had few armored or motorized forces and little heavy artillery were being depended on to filled the gaps that the Germans could no longer fill with their own troops. The reliance on these units would prove to be a key factor in the German defeat.

Army Group B provided the main effort and its offensive quickly smashed through the defending Soviet armies. By July 20th Hitler believed that “the Russian is finished.”[xii] One reason for the German success in the south was that until July 7th Stalin believed that Moscow was still the primary objective.[xiii] Despite his success, Von Bock was prevented by Hitler from destroying Soviet formations left behind his advance. He protested and was relieved of command by Hitler. Von Bock was replaced by Von Weichs which created a difficult command and control problem. Manstein noted that this created a “grotesque chain of command on the German southern wing” with the result that Army Group A had “no commander of its own whatever” and Army Group B had “no few than seven armies under command including four allied ones.”[xiv]

Panzer IV Ausf F Medium Tank

This decision proved fateful. Hitler decided to redirect the advance of the 4th Panzer Army to support an early passage of the lower Don, diverting it from its drive on Stalingrad. Additionally, the army groups became independent of each other when Bock was relieved of command. They were “assigned independent-and diverging-objectives” under the terms of Directive No.45.[xv] This combination of events would have a decisive impact on the campaign. The decision prevented a quick seizure of Stalingrad by 4th Panzer Army followed by a hand over to 6th Army to establish the “block” as described by Directive No.41. Field Marshal Ewald Von Kleist, now commanding Army Group A noted that he didn’t need 4th Panzer Army’s help to accomplish his objectives and that it could have “taken Stalingrad without a fight at the end of July….”[xvi]

The result of Hitler’s decision doomed the campaign. Air support and fuel needed by Army Group A was transferred to 6th Army, denuding Army Group A of the resources that it needed to conclude its conquest of the Caucasus.[xvii] At the same time it denied Army Group B of the Panzer Army that could have quickly seized Stalingrad when it was still possible to do so. Beevor calls Hitler’s decision a disastrous compromise.[xviii] Halder believed the decision underestimated the capabilities of the Red Army and was “both ludicrous and dangerous.”[xix]

All Eyes on Stalingrad

On July 22 as the Wehrmacht ran short on fuel and divisions to commit to the Caucasus, and the 6th Army fought for control of Voronezh, the Soviets created the Stalingrad Front to control operations in that city. Stavka moved an NKVD Division to the city,[xx] and rapidly filled the new front with formations transferred from the Moscow Front.[xxi]

Stalin issued Stavka Order 227, better known as “No Step Back” on 28 July. The order mandated that commanders and political officers who retreated would be assigned to Penal battalions[xxii]. It directed that each field Army was to form three to five special units of about 200 men each as a second line “to shoot any man who ran away.”[xxiii] Russian resistance west of the Don stiffened and slowed the German advance.

German commanders were astonished “at the profligacy of Russian commanders with their men’s lives.”[xxiv] Von Kleist compared the stubbornness of Russians in his area to those of the previous year and wrote that they were local troops “who fought more stubbornly because they were fighting to defend their homes.”[xxv] Additionally, Stalin changed commanders frequently in the “vain hope that a ruthless new leader could galvanize resistance and transform the situation.”[xxvi] General Vasily Chuikov brought the 64th Army into the Stalingrad Front in mid-July to hold the Germans west of the Don.[xxvii]

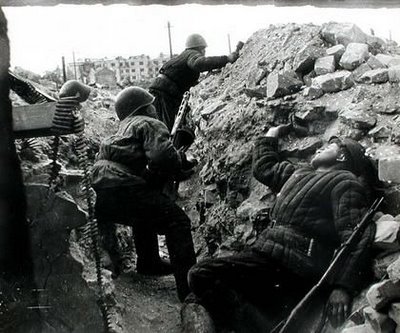

German Soldier in Stalingrad

The attacking German armies were weakened when the OKW transferred several key SS Panzer Divisions and the Grossdeutschland Division to France. The supporting Hungarian, Italian and Romanian allied armies lacked motorization, modern armor or anti-tank units and were unable to fulfill the gaps left by the loss of experienced German divisions and the unrealistic expectations of Hitler.[xxviii]

General Friedrich von Paulus

6th Army was virtually immobilized for 10 days due to lack of supplies. This allowed the Russians to establish a defense on the Don Bend.[xxix] To the south the Germans were held up by lack of fuel and increased Soviet resistance which included the introduction of a force of 800 bombers.[xxx]

Glantz and House noted that following the capture of Rostov on July 23rd, “Hitler abruptly focused on the industrial and symbolic value of Stalingrad.”[xxxi] Undeterred by warnings from Halder that fresh Russian formations were massing east of the Volga and the those of Quartermaster General Eduard Wagner, who guaranteed that he could supply either the thrust to the Caucasus or Stalingrad, but not both.[xxxii]

Again frustrated by slow the slow progress of the offensive, Hitler reverted to the original plan for 4th Panzer Army to assist 6th Army at Stalingrad. However, the cost in time and fuel necessitated by his changing of the plan in the first place were significant to the operation. Now the question for the Germans was whether “they could make up for Hitler’s changes in plan.”[xxxiii]

Strategic Implications

The changes in the German plan had distinct ramifications for both sides. General F. W. Von Mellenthin wrote of Hitler’s meddling, that “the diversion of effort between the Caucasus and Stalingrad ruined our whole campaign.”[xxxiv] The Germans were able not secure the Caucasus oil fields which Hitler considered vital to the German war effort. While they advanced deep into the region and captured the Maikop oil fields, the vital wells and refineries were almost completely destroyed by the retreating Red Army.[xxxv]

Army Group A was halted by the Russians along the crests of the Caucasus on August 28th.[xxxvi] This left Hitler deeply “dissatisfied with the situation of Army Group A.”[xxxvii] Kleist and others attributed much of the failure to a lack of fuel[xxxviii] and General Günther Blumentritt noted that Mountain divisions that could have made the breakthrough were employed along the Black Sea coast in secondary operations.[xxxix]

Fuel and supply shortages delayed 6th Army’s advance while General Herman Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army was needlessly shuttled between Rostov and Stalingrad. By the time it resumed its attack, the Russians “had sufficiently recovered to check its advance.”[xl] As 6th Army advanced to the East, the “protection of Army Group B’s ever-extending northern flank was taken over by the 3rd Rumanian, the 2nd Hungarian and the newly formed 8th Italian Army.”[xli] The allied armies were neither equipped for the Russian campaign nor were they well motivated for a campaign that offered them or their countries much benefit.[xlii]

The supply shortage in both army groups was not helped by a significant logistics bottleneck. All supplies for Army Group A and Army Group B had pass over a single crossing over the Dnieper River. Manstein noted that this prevented the swift movement of troops from one area to another.[xliii]

General Friedrich Von Paulus’ 6th Army now attempted to rush Stalingrad between the 25th and 29th of July, while Hoth milled about on the lower Don. However, Paulus’s piecemeal commitment of his divisions and failure to concentrate his army in the face of unexpectedly strong Soviet resistance caused the attacks to fail. Paulus was forced to halt 6th Army on the Don so it could concentrate its forces and build its logistics base [xliv] as well as to allow Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army to come up from the south.

The delay permitted the Russians to build up their forces west of Stalingrad, to reinforce the Stalingrad front, and to strengthen the defenses of the city. [xlv] Ince the Germans were now operating far from their logistics center, and. The Red Army was closer to its supply centers and due to the distances involved it was now far easier for the Russians to reinforce the Stalingrad front than it was for the Germans to supply their armies.[xlvi] The delay also allowed the Russians to fill a number of key leadership positions with the Generals who would skillfully fight the battle.[xlvii]

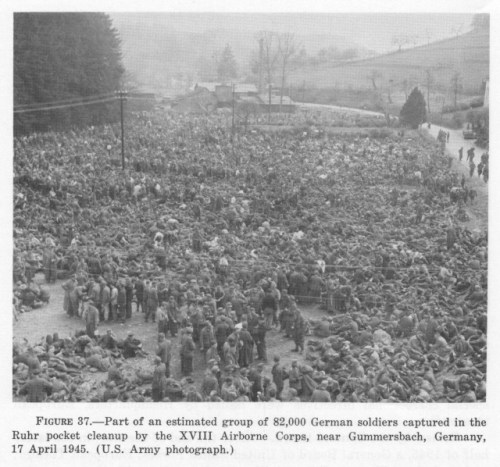

German Mountain Troops planting Swastika Flag on Mount Elbrus

Hitler now focused on the capture of Stalingrad despite the fact that “as a city Stalingrad was of no strategic importance.”[xlviii] Strategically, its capture would cut Soviet supply lines to the Caucasus,[xlix] but this objective could be have been achieved without its capture. The success of the Soviets in checking Army Group A’s advance in the Caucasus began to give Stalingrad a moral importance to Hitler , which was enhanced by its name. This came to outweigh its strategic value.”[l] To Hitler Stalingrad would gain “a mystic significance”[li] and along with Leningrad, still besieged by the Wehrmacht, became “not only military but also psychological objectives.”[lii]

The Germans mounted a frontal assault on Stalingrad with the 6th Army, supported by elements of the 4th Panzer Army, despite air reconnaissance that indicated “the Russians are throwing forces from all directions at Stalingrad.[liii] Paulus as the senior General was in charge of the advance, with Hoth subordinated to him, but the attack had to wait until Hoth’s army could fight its way up from the south.[liv] Von Mellenthin comments rightly that “when Stalingrad was not taken on the first rush, it would have been better to mask it….”[lv]

It is clear that the German advance had actually reached its culminating point with the failure of the advance into the Caucasus and Paulus’s initial setback on the Don, but it was not yet apparent to many involved.[lvi] The proper course of action would have been to halt and build up the front and create mobile reserve to parry any Russian offensive along northern flank while reinforcing success in the Caucasus. Manstein wrote that “by failing to take appropriate action after his offensive had petered out without achieving anything definite, he [Hitler] paved the way to the tragedy of Stalingrad!”[lvii]

Transfixed by Stalingrad

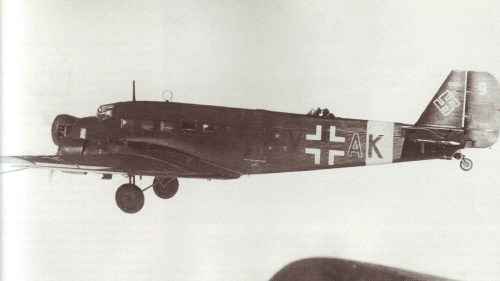

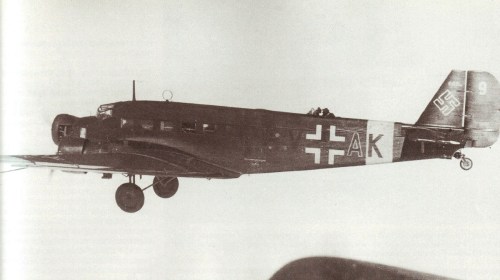

Luftwaffe Ju-52 Transport

On August 19th Paulus launched a concentric attack against the Russian 62nd and 64th Armies on the Don. The attack ran into problems, especially in Hoth’s sector.[lviii] Yet, on the 22nd the 14th Panzer Corps “forced a very narrow breach in the Russian perimeter at Vertyachi and fought its way across the northern suburbs of Stalingrad,”[lix] and reached the Volga on the 23rd. That day 4th Air Fleet launched 1600 sorties against the city dropping over 1,000 tons of bombs On the city. [lx]

The German breakthrough imperiled the Soviet position as they had concentrated their strongest forces against Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army.[lxi] The Germans maintained air superiority in the sector and the Luftwaffe continued its heavy bombing attacks.

During the last days of August the 6th Army “moved steadily forward into the suburbs of the city, setting the stage for battle.”[lxii] As the Soviets reacted to Paulus, Hoth finally achieved a breakthrough in the south which threatened the Russian position. However, the 6th Army was unable to disengage its mobile forces from the fight in the city to link up with the 4th Panzer Army and thus another opportunity had been missed.[lxiii]

As 6th Army moved into the city, General Andrey Yeromenko ordered attacks against General Hans Hube’s 16th Panzer Division. Soviet resistance increased, and as more Red Army formations arrived the Germans suffered “one of their heaviest casualty rates.”[lxiv] Though unsuccessful, the counterattacks “managed to deflect Paulus’s reserves at the most critical moment.”[lxv]

Despite this, the Germans remained confident the first week of September as 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army linked up, but Yeremenko saved his forces by withdrawing and avoided encirclement, and retired to an improvised line close to the city.[lxvi]

“Time is Blood”

General Vasily Chuikov at Stalingrad

On September 12th Chuikov was appointed to command 62nd Army in Stalingrad. Chuikov understood that there “was only one way to hold on. They had to pay in lives. ‘Time is blood,’ as Chuikov put it later.”[lxvii] Stalin sent Nikita Khrushchev to the front “with orders to inspire the Armies and civilian population to fight to the end.”[lxviii] The 13th Guards Rifle Division arrived on the 14th saved the Volga landings but it lost 30% casualties in its first 24 hours of combat.[lxix] An NKVD regiment and other units held the strategically sited high ground of Mamaev Kurgan, keeping German guns from controlling the Volga.[lxx]

The defenders fought house to house and block by block. Red Army and NKVD divisions were reinforced by Naval Infantry. Chuikov conducted the defense with a brutal ferocity, relieving senior commanders who showed a lack of fight and sending many officers to penal units. Chuikov funneled the massed German attacks into “breakwaters” where the panzers and infantry could be separated from each other causing heavy German casualties.[lxxi]

Communism Must be Deprived of Its Shrine

Now the “city became a prestige item, its capture ‘urgently necessary for psychological reasons,’ Hitler declared on October 2nd. A week later he declared that Communism must be ‘deprived of its shrine.’”[lxxii] Paulus’s troops continued to gain ground, however slowly and at great cost, especially among their infantry. Casualties were so heavy that companies had to be combined.

Chuikov used his artillery to interdict the Germans from the far side of the Volga where it was immune from ground attack. The fight in the city was fought by assault squads with incredible ferocity, and the close-quarter combat was dubbed “’Rattenkrieg’ by German soldiers.”[lxxiii]

Von Paulus brought more units into the city and continued to slowly drive the Russians back against the river, and by early October Chuikov wondered if he would be able to hold.[lxxiv] By early November Chuikov “was altogether holding only one-tenth of Stalingrad-a few factory buildings and a few miles of river bank.”[lxxv] Paulus now expected “to capture the entire city by 10 November,”[lxxvi] despite the fact that many of his units were fought out. The 6th Army Staff judged that 42% of the battalions of 51st Corps were fought out and no longer combat effective.[lxxvii] Even so, on November 9th, the 19th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler declared “No power on earth will force us out of Stalingrad again!”[lxxvi.]

Operation Uranus, the Soviet Counter Offensive

On September 24th Hitler relieved Halder as Chief of Staff of the Army for persisting in explaining “what would happen when new Russian reserve armies attacked the over-extended flank that ran out to Stalingrad.”[lxxix] Many Officers on the German side now recognized the danger. Blumentritt said “The danger to the long-stretched flank of our advance developed gradually, but it became clear early enough for anyone to perceive it who was not willfully blind.”[lxxx] Warnings of the danger were also given by Rumanian Marshall Antonescu and the staff sections of Army Group B and the 6th Army[lxxxi]. Despite this Hitler remained transfixed on Stalingrad and failed to allow his commanders to conduct operations that might be more successful elsewhere. In doing so the Germans gave up the advantage of uncertainty and once the German “aim became obvious…the Russian Command could commit its reserves with assurance.”[lxxxii]

In the midst of Stalin’s concern about Stalingrad Stavka planners never lost sight of their goal to resume large scale offensive operations as soon as possible in order to destroy at least one German Army Group.[lxxxiii] Unlike Hitler, Stalin had finally begun to trust his Generals. In September, Stavka under the direction of Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky produced a plan to cut off the “German spearhead at Stalingrad by attacking the weak Rumanian forces on its flanks.”[lxxxiv]

At first Stalin “showed little enthusiasm” for the attack, fearing that Stalingrad might be lost, but on 13 September he gave his full backing to the proposal. [lxxxv] Zhukov, Vasilevsky, and Vatutin developed into a plan involving two operations, Operation Uranus to destroy the German and allied forces at Stalingrad, and Operation Saturn to destroy all the German forces in the south, along with a supporting attack to fix German forces in the north, Operation Mars which was aimed at Army Group Center.[lxxxvi]

Soviet Armor Advancing to the Cheers of Civilians

To accomplish the destruction of 6th Army and part of 4th Panzer Army, Stavka employed over 60% of the “whole tank strength of the Red Army.”[lxxxvii] Strict secrecy combined with numerous acts of deception were used by the Red Army to disguise the operation.[lxxxviii] The plan involved an attack against 3rd Rumanian Army on the northern flank by 5th Tank Army and two infantry armies with supporting units.[lxxxix]

In the south against the 4th Rumanian Army and weak elements of the 4th Panzer Army, another force of over 160,000 men including 430 tanks were deployed.[xc] Despite warnings from his Intelligence Officer, Von Paulus did not expect a deep offensive into his flanks and rear and made no plans to prepare to face the threat.[xci] Other senior officers at OKW believed that the attack would take place against Army Group Center.[xcii] Warlimont notes that there was a “deceptive confidence in German Supreme Headquarters.”[xciii]

The storm broke on 19 November as Soviet forces attacked, rapidly crushing Romanian armies in both sectors[xciv] and linking up on November 23rd.[xcv] The 48th Panzer Corps which was deployed to support the Romanians was weak and had few operational tanks.[xcvi] It attempted a counterattack, but was “cut to pieces” in an encounter with 5th Tank Army.[xcvii]

A promising attempt by 29th Motorized division against the flank of the southern Russian pincer was halted by the Army Group and the division was ordered to take up defensive positions south of Stalingrad.[xcviii] Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe was neutralized by bad weather.[xcix] Von Paulus, in Stalingrad continued to do nothing since the attacks were outside of his area of responsibility, and waited for instructions from the Army Group. [c]

As a result the 16th and 24th Panzer Divisions which could have assisted matters to the west remained “bogged down in street-fighting in Stalingrad.”[ci] Without support 6th Army units west of Stalingrad were forced to,retreat in horrific conditions. By the 23rd, the 6th Army was cut off along with one corps of 4th Panzer Army and assorted Romanian units, a total over 330,000 men. The entrapped force would require the Soviets to use seven rifle armies and devote much staff attention to eliminate.[cii]

The Death of 6th Army

Hitler ordered Von Manstein to form Army Group Don to relieve Stalingrad. Hitler would not countenance any attempt by 6th Army to break out of the pocket and wanted Manstein to break through and relieve 6th Army.[ciii] Hitler refused a request by Paulus on 23 November to move troops to prepare for a possible a break out attempt, assuring him that he would be relieved.[civ]

Albert Speer notes that General Kurt Zeitzler, who replaced Halder insisted that the Sixth Army must break out to the west.”[cv] Hitler told Zeitzler that “We should under no circumstances give this up. We won’t get it back once it’s lost.”[cvi] Hermann Goering promised that the Luftwaffe would be able to meet the re-supply needs of 6th Army by air, even though his Generals knew that it was impossible with the number of transport aircraft available.[cvii]

Hitler took Goering at his word and exclaimed “Stalingrad can be held! It is foolish to go on talking any more about a breakout by Sixth Army…”[cviii] A Führer decree was issued ordering that the front be held at all costs.[cix] Walter Goerlitz wrote that “Hitler was incapable of conceiving that the 6th Army should do anything but fight where it stood.”[cx] Likewise Manstein had precious few troops with which to counterattack and he also had to protect the flank of Army Group A, which was still deep in the Caucasus and in danger of being cut off.

Field Marshal Erich von Manstein

His army group was only at corps strength and was spread across a 200 mile front.[cxi] Any relief attempt had to wait for more troops, especially Panzers divisions. Manstein too believed that the best chance for a breakout had passed and that it was a serious error for Paulus to put the request to withdraw through to Hitler rather than the Army Group or act on his own.[cxii] Many soldiers were optimistic that Hitler would get them out.[cxiii] Other generals like Guderian, Reichenau or Hoeppner might have acted, but Paulus was no rebel.[cxi]

Operation Saturn began on 7 December. The Red Army destroyed the Italian 8th Army and forced the Germans to parry the threat.[cxv] A relief attempt by 57th Panzer Corps under Hoth on 12 December made some headway until a massive Soviet counterattack on 24 December drove it back.[cxvi] This attack was hampered by OKW’s refusal to allocate the 17th Panzer and 16th Motorized divisions to Manstein,[cxvii] and by 6th Army not attacking out to link with the relief force.[cxviii]

By January 6th, Von Paulus signaled OKW “Army starving and frozen, have no ammunition and cannot move tanks anymore.”[cxix] On 10 January the Soviets launched Operation Ring to eliminate the pocket and despite all odds German troops fought on. On the 16th Paulus requested that battle worthy units be allowed to break out, but the request was not replied to by OKW. cxx] On January 22nd the last airfield was overrun, and on January 31st Paulus surrendered.[cxxi]

Analysis

Stalingrad had strangely drawn the attention of both sides, but the Russians never lost sight of their primary objectives during the campaign. The Germans on the other hand committed numerous unforced errors mostly caused by Hitler or Paulus. After the fall of Stalingrad as the Soviets attempted to follow up their success by attempted to cut off Army Group “A” Manstein was permitted to wage a mobile defense while Von Kleist managed to withdraw with few losses.[cxxii]

The superior generalship of Manstein and Von Kleist prevented the wholesale destruction of German forces in southern Russia, and Manstein’s counter offensive inflicted a severe defeat on the Soviets. However, the German Army had been badly defeated. The seeds of defeat were laid early, the failure to destroy bypassed Soviet formations in July, the diversion of 4th Panzer Army from Stalingrad, and the divergent objectives of trying to capture the Caucasus and Stalingrad at the same time. This diluted both offensives ensuring that neither succeeded. Likewise the failure to recognize the culminating point when it was reached and to adjust operations accordingly was disastrous for the Germans.

The failure create a mobile reserve to meet possible Russian counter offensives and the fixation on Stalingrad took the German focus off of the critical, yet weakly held flanks. The hubris of Hitler and OKW to believe that the Russians were incapable of conducting major mobile operations even as Stavka commenced offensive operations on those flanks all contributed to the defeat. Clark notes these facts, but adds that the Germans “were simply attempting too much.”[cxxiii]

Soviet numbers allowed them to wear down the Germans even in defeat.[cxxiv] At the same time Stalin gave his commanders a chance to revive the mobile doctrine of deep operations with mechanized and shock armies that he had discredited in the 1930s.[cxxv] Throughout the campaign Zhukov, Chuikov and other commanders maintained both their nerve even when it appeared that Stalingrad was all but lost. They never lost sight of their goal of destroying major German formations though they failed to entrap Army Group A in the Caucasus.

Notes

[i] Clark, Alan. Barbarossa: The Russian-German Conflict:1941-45. Perennial Books, An imprint of Harper Collins Publishers, New York, NY 1965. p.191

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Glantz, David M. and House, Jonathan. When Titan’s Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. The University Press of Kansas, Lawrence KS, 1995. p.111

[iv] Ibid. Clark. p.191

[v] Beevor, Anthony. Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege: 1942-1943. Penguin Books, New York NY 1998. p.69

[vi] Manstein, Erich von. Forward by B.H. Liddle Hart, Introduction by Martin Blumenson. Lost victories: The War Memoirs of Hitler’s Most Brilliant General. Zenith Press, St Paul MN 2004. First Published 1955 as Verlorene Siege, English Translation 1958 by Methuen Company. p.291 This opinion is not isolated, Beevor Quotes Paulus “If we don’t take Maikop and Gronzy…then I must put an end to the war.” (Beevor pp. 69-70) Halder on the other hand believed that Hitler emphasized that the objective was “the River Volga at Stalingrad. (Clark. p.190)

[vii] Ibid. Beevor. p.70.

[viii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.106

[ix] Ibid. p.105-106

[x] Ibid. Clark. p.203. The offensive did impose a delay on the German offensive.

[xi] Ibid. Clark. p.191 Each group also contained allied armies.

[xii] Ibid. p.209.

[xiii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.119

[xiv] Ibid. Manstein. p.292.

[xv] Ibid. Clark. p.209

[xvi] Ibid. Clark. p.211

[xvii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.120. There is a good discussion of the impact of this decision here as 6th Army’s advance was given priority for both air support and fuel.

[xviii] Ibid. Beevor. p.74

[xix] Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-45. Translated by R.H. Berry, Presido Press, Novato CA, 1964. p.249

[xx] Ibid. Beevor. p.75 This was the 10th NKVD Division and it took control of all local militia, NKVD, and river traffic, and established armored trains and armor training schools.

[xxi] Ibid. Clark. p.212

[xxii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.121

[xxiii] Ibid. Beevor. p.85

[xxiv] Ibid. p.89

[xxv] Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Quill Publishers, New York, NY 1979. Originally published by the author in 1948. p.202

[xxvi] Ibid. Beevor. p.88

[xxvii] Ibid. Beevor. p.90

[xxviii] Ibid. Beevor. p.81

[xxix] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.121

[xxx] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. p.202

[xxxi] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.120

[xxxii] Goerlitz, Walter. History of the German General Staff. Westview Press, Frederick A. Praeger Publisher, Boulder, CO. 1985 p.416

[xxxiii] Ibid. Beevor. pp.95-96.

[xxxiv] Von Mellenthin, F.W. Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the Second World War. Translated H. Betzler, Edited by L.C.F. Turner. Oklahoma University Press 1956, Ballantine Books, New York, NY. 1971. p.193

[xxxv] Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. A Touchstone Book published by Simon and Schuster, 1981, Copyright 1959 and 1960. p.914

[xxxvi] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.122

[xxxvii] Ibid. Warlimont. p.256

[xxxviii] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. p.203

[xxxix] Ibid. p.204

[xl] Ibid. Shirer. p.914

[xli] Ibid. Goerlitz. p.416

[xlii] Ibid. Goerlitz. p.416

[xliii] Ibid. Manstein. p.293

[xliv] Ibid. Clark. p.214

[xlv] Ibid. Beevor. pp.97-99. The mobilization included military, political, civilian and industrial elements.

[xlvi] Liddell-Hart, B.H. Strategy. A Signet Book, the New American Library, New York, NY. 1974, Originally Published by Faber and Faber Ltd., London. 1954 & 1967. p.250

[xlvii] Ibid. Beevor. p.99. Two key commanders arrived during this time frame, Colonel General Andrei Yeremenko, who would command the Stalingrad Front and General Chuikov commander of 64th Army who would conduct the defense of the city.

[xlviii] Carell, Paul Hitler Moves East: 1941-1943. Ballantine Books, New York, NY 1971, German Edition published 1963. p.581

[xlix] Ibid. Shirer. p.909.

[l] Ibid. Liddell-Hart, Strategy. p.250

[li] Wheeler-Bennett, John W. The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945. St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY 1954. p.531

[lii] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett. p.531

[liii] Ibid. Beevor. p.96

[liv] Ibid. Clark. p.216.

[lv] Ibid. Von Mellenthin. P.193

[lvi] See Von Mellinthin pp.193-194. Von Mellinthin quotes Colonel Dinger, the Operations Officer of 3rd Motorized Division at Stalingrad until a few days before its fall. Dingler noted that the Germans on reaching Stalingrad “had reached the end of their power. Their offensive strength was inadequate to complete the victory, nor could they replace the losses they had suffered.” (p.193) He believed that the facts were sufficient “not only to justify a withdrawal, but compel a retreat.” (p.194)

[lvii] Ibid. Manstein. p.294

[lviii] Ibid. Clark. p.216

[lix] Ibid. Clark. p.217

[lx] Ibid. Beevor. p.107

[lxi] Ibid. Beevor. p.107

[lxii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.122

[lxiii] Ibid. Carell. P.601

[lxiv] Ibid. Beevor. p.118

[lxv] Ibid. Beevor. p.118

[lxvi] Ibid. Carell. p.602

[lxvii] Ibid. Beevor. p.128

[lxviii] Ibid. Carell. p.603

[lxix] Ibid. Beevor. p.134

[lxx] Ibid. Beevor. pp.136-137

[lxxi] Ibid. Beevor. p.149

[lxxii] Fest, Joachim. Hitler. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich Publishers, San Diego, New York, London. 1974. p.661

[lxxiii] Ibid. Beevor. pp. 149-150

[lxxiv] Ibid. Beevor. p.164

[lxxv] Ibid. Carell. p.618

[lxxvi] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.123

[lxxvii] Ibid. Beevor. p.218

[lxxviii] Ibid. Carell. p.623

[lxxix] Ibid. Goerlitz. p.418

[lxxx] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. The German Generals Talk. p.207

[lxxxi] Ibid. Manstein. p292

[lxxxii] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. History of the Second World War. p.258

[lxxxiii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.129

[lxxxiv] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.130

[lxxxv] Ibid. Beevor. pp.221-222 Glantz and House say that Stalin gave his backing in mid-October but this seems less likely due to the amount of planning and movement of troops involved to begin the operation in November.

[lxxxvi] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.130

[lxxxvii] Ibid. Beevor. p.226

[lxxxviii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.132

[lxxxix] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.130

[xc] Ibid. Beevor. p.227

[xci] Ibid. Beevor. p.228

[xcii] Ibid. Clark. p.235

[xciii] Ibid. Warlimont. p.274

[xciv] Ibid, Carell. p.627 3rd Rumanian Army lost 75,000 men in three days.

[xcv] Ibid. Clark.pp.247-248

[xcvi] The condition of the few German Panzer Divisions in position to support the flanks was very poor, the 22nd had suffered from a lack of fuel and maintenance and this many of its tanks were inoperative. Most of the armor strength of the 48th Panzer Corps was provided by a Rumanian armored division equipped with obsolete Czech 38t tanks provided by the Germans.

[xcvii] Ibid. Clark. pp.251-252. The designation of 2nd Guards Tank Army by Clark has to be wrong and it is the 5th Tank Army as 2nd Guards Tank was not involved in Operation Uranus. Carell, Beevor and Glantz properly identify the unit.

[xcviii] Ibid. Carell. p.630

[xcix] Ibid. Beevor. p.244

[c] Ibid. Beevor. p.247

[ci] Ibid. Beevor. p.245

[cii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.134

[ciii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.134

[civ] Ibid. Clark. p.256

[cv] Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich. Collier Books, a Division of MacMillan Publishers, Inc. New York, NY 1970. p.248

[cvi] Heiber, Helmut and Glantz, David M. Editors. Hitler and His Generals: Military Conferences 1942-1945. Enigma Books, New York, NY 2002-2003. Originally published as Hitlers Lagebsprechungen: Die Protokollfragmente seiner militärischen Konferenzen 1942-1945. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt GmbH, Stuttgart, 1962. p.27

[cvii] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.135 Glantz and House note that the amount of aircraft estimated to successfully carry out the re-supply operation in the operational conditions was over 1,000. The amount needed daily was over 600 tons of which the daily reached only 300 tons only one occasion.

[cviii] Ibid. Speer. p.249

[cix] Ibid. Carell. p.636

[cx] Ibid. Goerlitz. p.426

[cxi] Ibid. Clark. p.252

[cxii] Ibid. Manstein. p.303

[cxiii] Ibid. Beevor. p.276

[cxiv] Ibid. Carell. p.640

[cxv] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.140

[cxvi] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.140

[cxvii] Ibid. Clark. p.264

[cxviii] Ibid. Manstein. p.337

[cxix] Ibid. Beevor. p320

[cxx] Ibid. Beevor. p.365

[cxxi] Of the approximately 330,000 in the pocket about 91,000 surrendered, another 45,000 had been evacuated. 22 German divisions were destroyed.

[cxxii] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. The German Generals Talk. p.211

[cxxiii] Ibid. Clark. p.250

[cxxiv] Ibid. Glantz and House. p.124

[cxxiv] Ibid. Beevor. p.221

Bibliography

Beevor, Anthony. Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege: 1942-1943. Penguin Books, New York NY 1998

Carell, Paul Hitler Moves East: 1941-1943. Ballantine Books, New York, NY 1971, German Edition published 1963.

Clark, Alan. Barbarossa: The Russian-German Conflict:1941-45. Perennial Books, An imprint of Harper Collins Publishers, New York, NY 1965.

Fest, Joachim. Hitler. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich Publishers, San Diego, New York, London. 1974

Glantz, David M. and House, Jonathan. When Titan’s Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. The University Press of Kansas, Lawrence KS, 1995.

Goerlitz, Walter. History of the German General Staff. Westview Press, Frederick A. Praeger Publisher, Boulder, CO. 1985

Heiber, Helmut and Glantz, David M. Editors. Hitler and His Generals: Military Conferences 1942-1945. Enigma Books, New York, NY 2002-2003. Originally published as Hitlers Lagebsprechungen: Die Protokollfragmente seiner militärischen Konferenzen 1942-1945. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt GmbH, Stuttgart, 1962.

Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Quill Publishers, New York, NY 1979. Originally Published by the author in 1948.

Liddell-Hart, B.H. Strategy. A Signet Book, the New American Library, New York, NY. 1974, Originally Published by Faber and Faber Ltd., London. 1954 & 1967

Manstein, Erich von. Forward by B.H. Liddle Hart, Introduction by Martin Blumenson. Lost victories: The War Memoirs of Hitler’s Most Brilliant General. Zenith Press, St Paul MN 2004. First Published 1955 as Verlorene Siege, English Translation 1958 by Methuen Company

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. A Touchstone Book published by Simon and Schuster, 1981, Copyright 1959 and 1960

Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich. Collier Books, a Division of MacMillan Publishers, Inc. New York, NY 1970.

Von Mellenthin, F.W. Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the Second World War. Translated H. Betzler, Edited by L.C.F. Turner. Oklahoma University Press 1956, Ballantine Books, New York, NY. 1971.

Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-45. Translated by R.H. Berry, Presido Press, Novato CA, 1964.

Wheeler-Bennett, John W. The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945. St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY 195

Knocked Out T-34s

Knocked Out T-34s Panzer IV F

Panzer IV F German Soldier in Stalingrad

German Soldier in Stalingrad

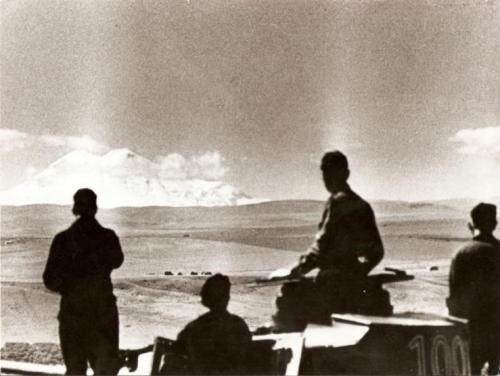

German Panzer Troops Look Upon the Caucasus Mountains

German Panzer Troops Look Upon the Caucasus Mountains JU-52: Despite Tremendous Bravery of Luftwaffe Pilots Goering Failed to Keep Stalingrad Supplied

JU-52: Despite Tremendous Bravery of Luftwaffe Pilots Goering Failed to Keep Stalingrad Supplied Soviet Armor on teh Offensive

Soviet Armor on teh Offensive T-34 in Stalingrad

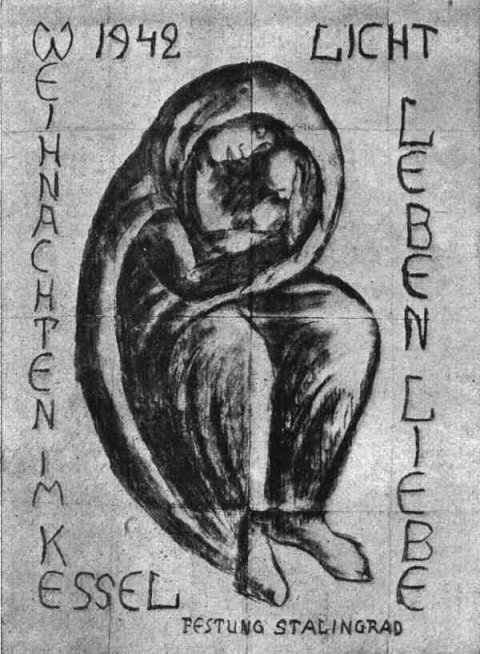

T-34 in Stalingrad The Madonna of Stalingrad

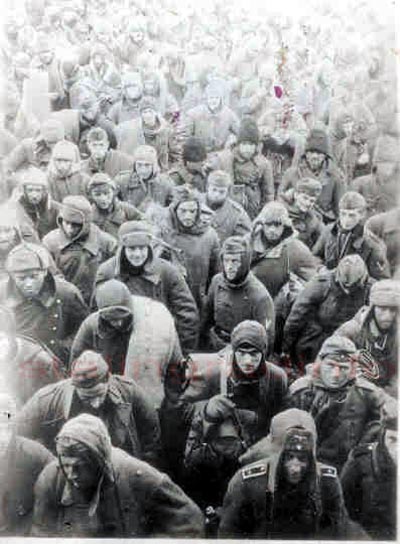

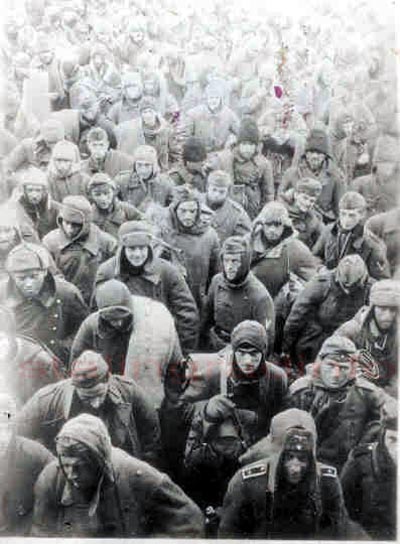

The Madonna of Stalingrad POWs: Only 5,000 of 90,000 POWs would return

POWs: Only 5,000 of 90,000 POWs would return Patton Bradley and Montgomery, Time Magazine Photo

Patton Bradley and Montgomery, Time Magazine Photo Troops and Tanks of 12th SS Panzer Division in Normandy

Troops and Tanks of 12th SS Panzer Division in Normandy American Armor Advancing

American Armor Advancing Fallschirmjaeger in France

Fallschirmjaeger in France Marker Garden, the Largest Airborne Operation

Marker Garden, the Largest Airborne Operation  American Troops in Holland

American Troops in Holland British Parachute Infantry in Arnhem

British Parachute Infantry in Arnhem