Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

I have been writing for some time about the coming demise of the Republican Party and the past few days I have been republishing sections of my draft text “Mine Eyes have Seen the Glory” Race, Religion, Ideology and Politics in the Civil War Era to show how the Whig and Democratic Parties imploded between 1850 and 1860.

Have a great day,

Peace,

padre Steve+

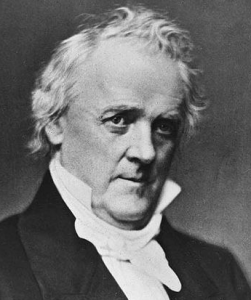

The fight over Lecompton was a watershed in American politics that those who wrote the Constitution of the United States could not have imagined. The deeply partisan fight served to illuminate how easily “minuscule minorities’ initial concerns ballooned into unmanageable majoritarian crises. The tiny fraction of Missouri slaveholders who lived near the Kansas border, comprising a tinier fraction of the South and a still tinier fraction of the Union, had demanded their chance to protect the southern hinterlands.” [1] The crisis that Kansas Democrats provoked drew in the majority of Southern Democrats who came to their aid in Congress and President Buchanan. This provoked Northerner, including Democrats to condemn the Southern minority, which they believed was disenfranchising the majority of people in the territory in order to expand slavery there and to other territories in the west.

The issue of Lecompton crisis galvanized the political parties of the North and demolished any sense of national unity among the Democrats. The split in the Democratic Party mirrored the national divide and the party split into hostile Northern and Southern factions, which doomed it as a national party for the foreseeable future.

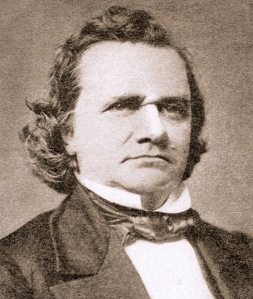

Following Lecompton the intra-party Democrat divide widened as “Pro-Douglas and pro-Buchanan Democrats openly warred on one another for the next two years; an unacknowledged but real split had taken place.” [2]

The battle over the Lecompton Constitution also marked the first time that a coalition Northern Democrats sided with anti-slavery forces to defeat pro-slavery legislation in congress. Though the measure to admit Kansas as a slave state was defeated it was a narrow victory; the “Republicans and anti-Lecompton Douglas Democrats, Congress had barely turned back a gigantic Slave Power Conspiracy to bend white men’s majoritarianism to slavemaster’s dictatorial needs, first in Kansas, then in Congress.” [3]

The political impact of the Lecompton crisis on the Democratic Party was an unmitigated disaster. The party suffered a major election defeat in the 1858 mid-term elections and lost its majority in the House of Representatives even though it barely maintained a slim majority in the Senate. While the victorious Republicans had won the election, they made little legislative headway since the Democrats still controlled the Senate and James Buchanan remained President. In a sense “there were two Democratic parties: one northern, on southern (but with patronage allies in the north); one having its center of power in the northern electorate and in the quadrennial party convention… the other with its center of power in Congress; one intent on broadening the basis of support to attract moderate Republicans, the other more concerned to preserve a doctrinal defense of slavery even if it meant driving heretics out of the party.” [4] Democratic Party divide fulfilled what Lincoln had said about the country, as the Democratic Party had “became increasingly a house divided against itself.” [5]

Douglas’s courageous opposition to the fraud of Lecompton would be the chief reason for the 1860 split in the Democratic Party as Southern Democrats turned with a vengeance on the man who had been their standard bearer during the 1856 Democratic primary. “Most southern Democrats went to Charleston with one overriding goal: to destroy Douglas.” [6] The party decided to meet in the Charleston to decide on their platform and the man who would be their standard bearer in the election of 1860. When the convention met in April 1860 it rapidly descended into a nightmare for the Democrats as “Southern delegates were much more intent on making a point than on nominating a presidential candidate.” [7] The “Southern delegates demanded a promise of federal protection of slavery in all the territories and a de facto veto in the selection of the party’s presidential candidate” [8] in order to block the nomination of Douglas. Southern radicals “led by William Lowndes Yancey of Alabama stood for seven days agitating for a pro-slavery platform.” [9]

Ohio Democrat George A. Pugh responded to the Southern fire-eaters and said that “Northern Democrats had worn themselves out defending Southern interests – and he declared that the Northern Democrats like himself were now being ordered to hide their faces and eat dirt.” [10] Georgia Senator Alexander Stephens who had moderated his position and was supporting Douglas wrote that the radicals “strategy was to “rule or ruin.” [11] When their attempts to place the pro-slavery measures into the party platform were defeated by Northern delegates, it prompted “a walkout by delegates from Alabama, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.” [12] This deprived Douglass of the necessary two thirds majority needed for the nomination and “the shattered convention adjourned, to reconvene in Baltimore on June 18,” [13] the “incendiary rhetoric left the Democratic Party in ashes.” [14] A friend of Alexander Stephens suggested that the party might patch things up in Baltimore, but Stephens dismissed the suggestion and told his friend, “The party is split forever. The only hope was in Charleston.” [15]

Old line former Whigs who feared the disintegration of the country led by Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden formed their own convention, the Constitutional Union Party and declared a pox on both the Buchanan and Douglas factions of the Democratic Party. They nominated a rather cold and uninspiring moderate slave owner, the sixty-four year old John Bell of Tennessee as their candidate for Constitutional Union Party President and “then chose a man who overshadowed him, Edward Everett of Massachusetts, aged sixty-seven, as the vice-presidential nominee.” [16] But this ticket had no chance of success, Bell “stood for moderation and the middle road in a country that just now was not listening to moderates, and the professional operators were not with him.” [17]

When the Democratic Party convention reconvened the results were as Stephens predicted. Another walk out by Southern delegates resulted in another and this time a final split. “Rival delegations from the Lower South States arrived in Baltimore, one side pledged to Douglas and the other to obstruction. When the convention voted for the Douglas delegations, the spurned delegates walked out, this time joined by colleagues from the Upper South.” [18] Though Douglas did not have the two-thirds majority, the convention “adopted a resolution declaring Douglas unanimously nominated.” [19] A day later the radicalized Southern delegates nominated their own candidate, the current Vice President, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky as their candidate “for president on a slave-code platform.” [20]

There were now four presidential tickets, three composed of Democrats and former Whigs, “each supported by men who felt that they were following the only possible path to salvation. A Republican victory was almost certain, and the Democrats, who had the most to lose from such a victory, were blindly and with a fated stubbornness doing everything they could to bring that victory to pass.” [21]

The Democratic Party had imploded and doomed the candidacies of Douglas and Breckinridge. The Augusta Daily Chronic and Sentinel editorialized, “It is an utterly futile and hopeless task to re-organize, re-unite and harmonize the disintegrated Democratic party unless this is to be done by a total abandonment of principle… No, sensible people might as well make up their minds to the fact that the Democratic party is dissolved forever, that new organizations must take its place.” [22]

Notes

[1] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.140

[2] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.213

[3] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.142

[4] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.394

[5] Fehrenbacher, Don E. Kansas, Republicanism, and the Crisis of the Union in The Civil War and Reconstruction Documents and Essays Third Edition edited by Michael Perman and Amy Murrell Taylor Wadsworth Cengage Learning Boston MA 2011 p.94

[6] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.213

[7] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.167

[8] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.216

[9] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.121

[10] Ibid. Catton The Coming Fury p.32

[11] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.215

[12] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.167

[13] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.121

[14] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.167

[15] Ibid. Catton The Coming Fury p.46

[16] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.417

[17] Ibid. Catton The Coming Fury p.46

[18] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.168

[19] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.413

[20] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.216

[21] Ibid. Catton The Coming Fury p.69

[22] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.121