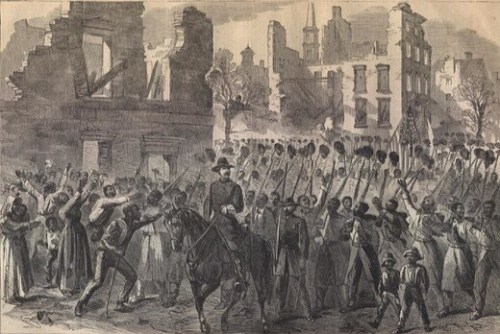

Union U.S.C.T. Troops march into Richmond

Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

As I have been doing the past few days I am posting another heavily revised section of my Civil War and Gettysburg text. This one deals with the less than successful efforts of some in the Confederacy to deal with reality and recommend that the Confederacy emancipate African American slaves. It really is a fascinating study that I expect to do more work on, but I think that youn will find it quite informative.

Until tomorrow,

Peace

Padre Steve+

In the South where before the war about forty percent of the population was composed of African American slaves there was no question regarding abolition or enlistment of African American soldiers. The Confederate States of America was a pro-slavery nation which hoped to “turn back the tide of abolition that had swept the hemisphere in the Age of Revolution…. Confederate founders proposed instead to perfect the slaveholder’s republic and offer it to the world as the political form best suited to the modern age.” [1]

The political and racial ideology of the South, which ranged from benevolent paternal views of Africans as less equal to whites, moderate prejudice and at tolerance of the need for slavery, and extreme slavery proponents who wanted to expand the institution beyond the borders of the Confederacy, as well as extreme prejudice and race race-hatred; was such that almost until the end of the war, Confederate politicians and many senior Confederate officers fought against any allowance for blacks to serve; for they knew if they allowed this, that slavery itself must be swept away. As such, it was not until 1864 when the Confederacy was beginning to face the reality that they could no longer win the war militarily, that any serious discussion of the subject commenced.

But after the fall of Vicksburg and the shattering defeat at Gettysburg, some Southern newspapers in Mississippi and Alabama began to broach the subject of employing slaves as soldiers, understanding the reality that doing so might lead to emancipation, something that they loathed but understood the military and political reality for both if the Confederacy was to gain its independence from the Union. The editor of the Jackson Mississippian wrote that, “such a step would revolutionize our whole industrial system” and perhaps lead to universal emancipation, “a dire calamity to both the negro and the white race.” But if we lose slavery anyway, for Yankee success is death to the institution… so that it is a question of necessity – a question of choice of evils. … We must… save ourselves from the rapacious north, WHATEVER THE COST.” [2]

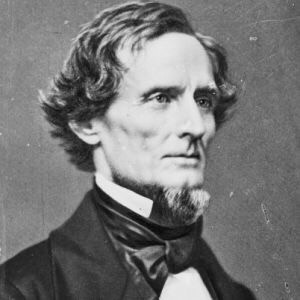

The editor of the Montgomery Daily Mail “worried about the implications of arming slaves for “our historical position on the slavery question,” as he delicately put it. The argument which goes to the exclusion of negroes as soldiers is founded on the status of the negro.” Negroes, he asserted, are “racially inferior[s],” but “the proposition to make the soldiers… [would be but a] practical equalization of the races.” Nonetheless they had to do it. “The War has made great changes,” he insisted, and, “we must meet those changes for the sake of preserving our existence. They should use any means to defeat the enemy, and “one of those, and the only one which will checkmate him, is the employment of negroes in the military services of the Confederacy.” [3] Other newspapermen noted “We are forced by the necessity of our condition,” they declared, “to take a step which is revolting to every sentiment of pride, and to every principle that governed our institutions before the war.” The enemy was “stealing our slaves and converting them into soldiers…. It is better for us to use the negroes for our defense than that the Yankees should use them against us.” [4] These were radical words, but neither Jefferson Davis, nor the Confederate Congress was willing to hear them, and the topic remained off the table as a matter of discussion.

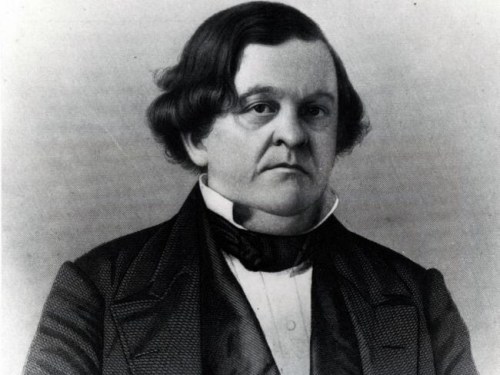

Major General Patrick Cleburne CSA

Despite this, there were a few Confederate military leaders who understood that the South could either fight for freedom and independence from the Union, but not for slavery at the same time, especially if the Confederacy refused to mobilize its whole arms-bearing population to defeat the Union. The reality that the “necessity of engaging slaves’ politics was starting to be faced where it mattered most: in the military.” [5] One of these men was General Patrick Cleburne, an Irish immigrant and a division commander in the Army of Tennessee who demonstrated the capacity for forward thinking in terms of race, and political objectives far in advance of the vast majority of Confederate leaders and citizens. Cleburne openly advocated that blacks should be allowed to serve as soldiers of the Confederacy, and that they should be emancipated.

Cleburne, who was known as “the Stonewall Jackson of the West” was a bold fighter who put together a comprehensive plan to reverse the course of the war by emancipating slaves and enlisting them to serve in the Confederate military. Cleburne was a lawyer, and his proposal was based on sound logic. Cleburne noted that the Confederacy was losing the war because it did not have enough soldiers, supplies, or resources to sustain the war effort. He stressed that the South had an inadequate number of soldiers, and that “our soldiers can see no end… except in our own exhaustion; hence, instead of rising to the occasion, they are sinking into a fatal apathy, growing weary of hardships and slaughters which promise no results.” [6]

Most significantly the Irishman argued that “slavery, from being one of our chief sources of strength at the beginning of the war, has now become in a military point of view, one of our chief sources of weakness,” [7] and that “All along the lines… slavery is comparatively valueless to us for labor, but of great and increasing worth to the enemy for information,” an “omnipresent spy system, pointing out our valuable men to the enemy, revealing our positions, purposes, and resources.” [8] He noted, that “Every soldier in our army already knows and feels our numerical inferiority to the enemy…. If this state continues much longer we shall surely be subjugated.” [9]

Cleburne was the ultimate realist in terms of what was going on in the Confederacy and the drain that slavery and the attempts to control the slave population were having on it. The Conscription Act of 1862 acknowledged that men had to be retained at home in order to guard against slave uprisings, and how exemptions diminished forces at the front without adding any corresponding economic value. Cleburne wrote of how African Americans in the South were becoming increasingly pro-Union, and were undermining Southern morale at home and in the ranks. He noted that they brought up “fear of insurrection in the rear” and filled Confederate soldiers with “anxieties for the fate of loved ones when our armies have moved forward.” And when Union forces entered plantation districts, they found “recruits waiting with open arms.” There was no point in denigrating their military record, either. After donning Union blue, black men had proved able “to face and fight bravely against their former masters.” [10]

Cleburne’s proposal was radical for he recommended that “we immediately commence training a large reserve of the most courageous of our slaves, and further that we guarantee freedom within a reasonable time to every slave in the South who shall remain to the confederacy in this war.” [11] Cleburne’s realism came through in his appeal to the high command:

“Ever since the agitation of the subject of slavery commenced the negro has been dreaming of freedom and his vivid imagination has surrounded the condition with so many gratifications that it has become the paradise of his hopes.” It was also shrewd politically: “The measure we propose,” he added, “will strike dead all John Brown fanaticism, and will compel the enemy to draw off altogether or in the eyes of the world to swallow the Declaration of Independence without the sauce and disguise of philanthropy.” [12]

The Irishman’s “logic was military, the goal more men in uniform, but the political vision was radical indeed.” [13] He was asking more from his fellow Southerners than most were willing to risk, and even more than Lincoln had asked of the North in his Emancipation Proclamation. Cleburne was “asking them to surrender the cornerstone of white racism to preserve their nation” [14] something that most seemed even unwilling to consider. He presented his arguments in stark terms that few Southern leaders, or citizens could stomach “As between the loss of independence and the loss of slavery, we can assume that every patriot will freely give up the latter- give up the Negro slave rather than be a slave himself.” [15] Cleburne’s words were those of a heretic, he noted “When we make soldiers of them we must make free men of them beyond all question…and thus enlist their sympathies also.” [16] But Cleburne’s appeal would be quashed in Richmond.

In January 1864 General W.H.T Walker obtained a copy of Cleburne’s proposal and sent it to Jefferson Davis. Walker opposed it and expressed his outrage over it. Cleburne’s proposal went from being a military matter to a political matter, and in Walker’s opinion, the political arguments were out of line for any military officer to state in public. Jefferson Davis intervened to quash the proposal, as he could only see negative results coming from it. Davis was “Convinced that the “propagation of such opinions” would cause “discouragements, distraction, and dissension” in the army,” and he “ordered the Generals to stop discussing the matter…The only consequence of Cleburne’s action seemed to be the denial of promotion to this ablest of the army’s division commanders, who was killed ten months later at the Battle of Franklin.” [17] In fact Cleburne was “passed over for command of an army corps and promotion to lieutenant general” three times in the next eight months, and in “each care less distinguished, less controversial men received the honors.” [18] All copies of Cleburne’s proposal were destroyed by the War Department on the order of Davis.

Cleburne was not the only military man to advocate the formation of Negro units or even emancipation. Richard Ewell suggested to Jefferson Davis the idea of arming the slaves and offering them emancipation as early as 1861, and Ewell went as far as “volunteering to “command a brigade of Negroes.” [19] During the war Robert E. Lee became one of the chief proponents of this. Lee said after the war that he had told Davis “often and early in the war that the slaves should be emancipated, that it was the only way to remove a weakness at home and to get sympathy abroad, and divide our enemies, but Davis would not hear of it.” [20]

Ten months later Davis raised the issue of arming slaves, as he now, quite belatedly, believed that military necessity left him little choice. On November 7th 1864 he made his views known to the Confederate Congress, and they were a radical departure from the hitherto political orthodoxy of slavery. Davis had finally come to the realization the institution of slavery was now useless to the Confederate cause, as he had become a more ardent Confederate nationalist, and to Davis, “Preserving slavery had become secondary to preserving his new nation,” [21] and his words shocked the assembled Congress. The slave, he boldly declared that “the slave… can no longer be “viewed as mere property” but must be recognized instead in his other “relation to the state – that of a person.” As property, Davis explained, slaves were useless to the state, because without the “loyalty” of the men could be gained from their labor.” [22]

In light of the manpower needs of the South as well as the inability to achieve foreign recognition Davis asked their “consideration…of a radical modification in the theory of law” of slavery…” and he noted that the Confederacy “might have to hold out “his emancipation …as a reward for faithful service.” [23]

This drew the opposition of previously faithful supporters and in the press, especially that of North Carolina. Some newspapers in that state attacked Davis and his proposal, as “farcical” – “all this done for the preservation and perpetuation of slavery,” and if “sober men… are ready to enquire if the South is willing to abolish slavery as a condition of carrying on the war, why may it not be done as a condition of ending the war?” [24] Likewise, Davis now found himself opposed by some of his closest political allies including Robert Toombs and Howell Cobb. Toombs roared, “The day that the army of Virginia allows a negro regiment to enter their lines as soldiers they will be degraded, ruined, and disgraced.” [25] Likewise, Cobb warned “The day that you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” [26] Some in the military echoed his sentiments, Brigadier General Clement H. Stevens of South Carolina declared “I do not want independence if it is to be won by the help of the Negro.” [27] A North Carolina private wrote, “I did not volunteer to fight for a free negroes country…. I do not think I love my country well enough to fight with black soldiers.” [28]

Robert E. Lee, who had emancipated his slaves before the war, began to be a formidable voice in the political debate going on in the Confederacy regarding the issue of blacks serving as soldiers and emancipation. He wrote to a member of Virginia’s legislature: “we must decide whether slavery shall be extinguished by our enemies and the slaves used against us, or use them ourselves at the risk of the effects which may be produced on our social institutions…” and he pointed out that “any act for the enrolling of slaves as soldiers must contain a “well digested plan of gradual and general emancipation”: the slaves could not be expected to fight well if their service was not rewarded with freedom.” [29] He wrote another sponsor of a Negro soldier bill “The measure was “not only expedient but necessary…. The negroes, under proper circumstances will make effective soldiers. I think we could do as well with them as the enemy…. Those employed should be freed. It would be neither just nor wise… to require them to serve as slaves.” [30]

When Howell Cobb heard of Lee’s support for black soldiers and emancipation he fired of a letter to Secretary of War Seddon, “I think that the proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has ever been suggested since the war began. It is to me a source of deep mortification and regret to see the name of that good and great man and soldier, General R. E. Le, given as authority for such policy.” [31]

The debate which had begun in earnest in the fall of 1864 revealed a sharp divide in the Confederacy between those who supported the measure and those against it. Cabinet members such as Judah Benjamin and a few governors “generally supported arming the slaves.” [32] The Southern proponents of limited emancipation were opposed by the powerful governors of Georgia and North Carolina, Joe Brown and Zebulon Vance, and by the President pro-tem of the Confederate Senate R.M.T. Hunter, who forcibly opposed the measure. Senator Louis Wigfall who had been Davis’s ally in the conscription debates, now became his opponent, he declared that he “wanted to live in no country in which the man who blacked his boots and curried his horse was his equal.” [33]

Much of the Southern press added its voice to the opposition. Newspapers in North Carolina declared the proposal “farcical” – “all this was done for the preservation and the perpetuation of slavery,” and if “sober men…are willing to enquire if the South is willing to abolish slavery as a condition of carrying on the war, why may it not be done, as a condition of ending the war?” [34] The Charleston Mercury considered the proposal apostasy and proclaimed “Assert the right in the Confederate government to emancipate slaves, and it is stone dead…” [35] In Lynchburg an editor noted, “If such a terrible calamity is to befall us… we infinitely prefer that Lincoln shall be the instrument pf our disaster and degradation, that we ourselves strike the cowardly and suicidal blow.” [36]

Some states in the Confederacy began to realize that slaves were needed in the ranks, but did not support emancipation. Led by Governor “Extra Billy” Smith, Virginia’s General Assembly finally approved a law in 1865 “to permit the arming of slaves but included no provision for emancipation, either before or after military service.” [37] Smith declared that without slavery the South “would no longer have a motive to fight.” [38]

Many Confederate soldiers displayed the attitude that would later propel them into the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan, the Red Shirts, the White League and the White Liners after the war. A North Carolina soldier wrote, “I did not volunteer to fight for a free negroes country… I do not think I love my country well enough to fight with black soldiers.” [39]

But many agreed with Lee, including Silas Chandler of Virginia, who stated, “Gen Lee is in favor of it I shall cast my vote for it I am in favor of giving him any thing he wants in the way of gaining our independence.” [40] Finally in March of 1865 the Confederate Congress passed by one vote a watered down measure of the bill to allow for the recruitment of slaves. It stipulated that “the recruits must all be volunteers” [41] and those who volunteered must also have “the approbation of his master by a written instrument conferring, as far as he may, the rights of a freed man.” [42] While this in itself was a radical proposition for a nation which had went to war to maintain slavery, the fact was that the slave’s service and freedom were granted not by the government, but by his owner, and even at this stage of the war, few owners were willing to part with their property. It was understood by many that giving freedom to a few was a means of saving the “particular institution.” The Richmond Sentinel noted during the November debate: “If the emancipation of a part is the means of saving the rest, this partial emancipation is eminently a pro-slavery measure.” [43] Thus the law made “no mention of emancipation as a reward of military service” [44] and in deference to “state’s rights, the bill did not mandate freedom for slave soldiers.” [45]

But diehards opposed even the watered down measure. Robert Kean, who headed the Bureau of War and should have understood the stark reality of the Confederacy’s strategic situation, note in his diary, that the law:

“was passed by a panic in the Congress and the Virginia Legislature, under all the pressure the President indirectly, and General Lee directly, could bring to bear. My own judgment of the whole thing is that it is a colossal blunder, a dislocation of the foundations of society from which no practical results will be reaped by us.” [46]

It was Lee’s prestige alone that allowed the measure to pass, but even that caused some to question Lee’s patriotism. The Richmond Examiner dared to express a doubt whether Lee was “a ‘good Southerner’: that is, whether he is thoroughly satisfied of the justice and beneficence of negro slavery.” [47] Robert Toombs of Georgia stated that “the worst calamity that could befall us would be to gain our independence by the valor of our slaves” [48] and a Mississippi congressman stated, “Victory itself would be robbed of its glory if shared with slaves.” [49]

But even if the final bill passed was inadequate, the debate had finally forced Southerners “to realign their understanding of what they were protecting and to recognize the contradictions in their carefully honed rationalization. Some would still staunchly defend it; others would adopt the ostrich’s honored posture. But many understood only too well what they had already surrendered.” [50]

On March 23rd 1865 the War Office issued General Order Number 14, which authorized the call up and recruitment of slaves to the Confederate cause. The order read in part: “In order to provide additional forces to repel invasion…the President be, and he is hereby authorized to ask for and to accept from the owners of slaves, the services of such able-bodied negro men as he may deem expedient, for and during the war, to perform military service in whatever capacity he may direct…” While the order authorized that black soldiers “receive the same rations, clothing and compensation as are allowed to other troops in the same branch of service,” it did not provide for the emancipation of any of the black soldiers that might volunteer. Instead it ended “That nothing in this act shall be construed to authorize a change in the relation which the said slaves shall bear to their owners, except by the consent of the owners and of the States which they may reside….” [51]

Twelve days after the approval of the act, on March 25th two companies of blacks were formed for drill in Richmond’s Capitol Square. As the mobilized slaves assembled to the sounds of fifes and drums they were met with derision and violence as even “Small boys jeered and threw rocks” [52] at them. None of those few volunteers would see action as within a week the Confederate government had fled Richmond, leaving them and the capital at the mercy of the victorious Union army. .

But some would see that history was moving, and attitudes were beginning to change. It took time, and the process is still ongoing. As imperfect as emancipation was and though discrimination and racism remained, African Americans had reached “levels that none had ever dreamed possible before the war.” [53] In April 1865 as Jefferson Davis and his government fled Richmond, with Davis proclaiming, “again and again we shall return, until the baffled and exhausted enemy shall abandon in despair his endless and impossible task of making slaves of a people resolved to be free.” [54]

The irony in Davis’s empty vow was stunning. Within a week Lee had surrendered and in a month Davis himself would be in a Federal prison. In the wake of his departure the Confederate Provost Marshall set fire to the arsenal and the magazines to keep them from falling into Union hands. However, the fires “roared out of hand and rioters and looters too to the streets until the last Federal soldiers, their bands savagely blaring “Dixie,” marched into the humiliated capital and raised the Stars and Stripes over the old Capitol building.” [55]

The Federal troops who led the army into Richmond came from General Godfrey Weitzel’s Twenty-fifth Corps, of Ord’s Army of the James. The Every black regiment in the Army of the James was consolidated in Weitzel’s Corps, along with Ferrero’s former division that had suffered so badly at the Battle of the Crater. “Two years earlier in New Orleans, Weitzel had protested that he did not believe in colored troops and did not want to command them, and now he sat at the gates of Richmond in command of many thousands of them, and when the citadel fell he would lead them in and share with them the glory of occupying the Rebel capital.” [56] Among Weitzel’s units were regiments of black “cavalrymen and infantrymen. Many were former slaves; their presence showed their resolve to be free.” [57]

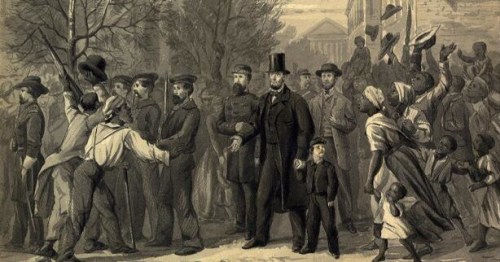

On April 4th 1865 Abraham Lincoln entered Richmond to the cheers of the now former slaves still in the city. A journalist described the scene,

“The gathered around the President, ran ahead, hovered upon the flanks of the little company, and hung like a dark cloud upon the rear. Men, women, and children joined the consistently increasing throng. They came from the by-streets, running in breathless haste, shouting and hallooing and dancing with delight. The men threw up their hats, the women their bonnets and handkerchiefs, clapped their hands, and sang, Glory to God! Glory! Glory! Glory!” [58]

One old man rushed to Lincoln and shouted “Bless the Lord, the great Messiah! I knowed him as soon as I seed him. He’s been in my heart four long years, and he’s come at last to free his children from their bondage. Glory, hallelujah!” He then threw himself at the embarrassed President’s feet and Lincoln said, “Don’t kneel to me. You must kneel to God only, and thank Him for the liberty you will enjoy hereafter.” [59]

Emancipation had finally arrived in Richmond, and in the van came the men of the U.S. Colored Troops who had rallied to the Union cause, followed by the man who had made the bold decision to emancipate them and then persevere until that was reality.

Notes

[1] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.310

[2] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.832

[3] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.324

[4] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.831

[5] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.325

[6] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie p.167

[7] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.262

[8] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie p.167

[9] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.326

[10] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie p.167

[11] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.262

[12] Winik, Jay April 1865: The Month that Saved America Perennial an Imprint of Harper Collins Publishers New York 2002 p.53

[13] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.327

[14] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[15] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.262

[16] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.327

[17] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.833

[18] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.262

[19] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[20] Ibid. Gallagher The Confederate War p.47

[21] Ibid. Davis, William C. Jefferson Davis p.598

[22] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.335

[23] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.335

[24] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[25] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.835

[26] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[27] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.55

[28] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[29] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.643

[30] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.836

[31] Cobb, Howell Letter to James A. Seddon, Secretary of War, January 8, 1865 in the Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader: The “Great Truth” about the “Lost Cause” Loewen, James W. and Sebesta, Edward H. Editors, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson 2010 Amazon Kindle edition location 4221 of 8647

[32] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.293

[33] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.836

[34] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[35] Ibid. McCurry Confederate Reckoning p.337

[36] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.836

[37] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three pp.754-755

[38] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[39] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 370

[40] Ibid. Pryor Reading the Man p.396

[41] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p. 755

[42] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.296

[43] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.836

[44] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.755

[45] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.837

[46] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.860

[47] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.837

[48] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.860

[49] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.835

[50] Ibid. Pryor Reading the Man p.397

[51] Confederate Congress General Orders, No. 14, An Act to Increase the Military Force of the Confederate States, Approved March 13, 1865 in the Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader: The “Great Truth” about the “Lost Cause” Loewen, James W. and Sebesta, Edward H. Editors, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson 2010 Amazon Kindle edition location4348 of 8647

[52] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.860

[53] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 386

[54] Levine, Bruce Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of the Civil War Revised Edition, Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York 1992 and 1995 p.241

[55] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 476

[56] Catton, Bruce Grant Takes Command Little, Brown and Company Boston, Toronto and London 1968 p.411

[57] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free pp.241-242

[58] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie p.275

[59] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.897