Hagerman, Edward. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare. Midland Book Editions, Indiana University Press. Bloomington IN. 1992

Pickett’s Charge Displayed the Futility of Napoleonic Tactics Against Modern Weaponry

Pickett’s Charge Displayed the Futility of Napoleonic Tactics Against Modern Weaponry

Edward Hagerman postulates in The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare that the American Civil War is the first modern war. He examines developments in tactics, logistics and the concept of total war and looks specifically how tactical and strategic thought impacted the war. Specifically Hagerman examines how Henri Jomini’s interpretation of Napoleonic warfare and the theories of Dennis Hart Mahan and Henry Halleck which were the prevalent military thought in America were challenged by advances in weaponry and the vastness of the American continent. He surveys how the Union and Confederate armies learned the value and application of field fortifications and the limitations of artillery in the offense. Even more importantly Hagerman argues how logistics influenced campaigning on the American continent as opposed to earlier European wars. Likewise he examines how the 20th Century concept of total war found its first application in the campaigns of General Sherman and how Robert E. Lee’s use of defensive maneuver and fortifications in positional warfare heralded a new era in warfare.

Dennis Hart Mahan’s Book: The First American Book on Military Theory

Dennis Hart Mahan’s Book: The First American Book on Military Theory

Hagerman examines how these factors influence and affected the Union and Confederate armies. His initial focus is the tactical conundrum posed by the advances weaponry particularly the rifled musket to the Napoleonic tactics that both armies began the war. Napoleonic tactics were developed at a time when the maximum effective range of muskets was barely 100 meters and how despite the increase in range and accuracy that came with the rifled musket how tactical formations and tactics were slow to change.

Hagerman spends the first part of his book examining how the ante-bellum US Army leadership was influenced by the theories of Henri Jomini. He discusses the challenge to Jominian orthodoxy by Dennis Hart Mahan, who modified “the current orthodoxy by rejecting its central tenants-primarily offensive assault tactics.”[i] He examines the tension in American military thought between the conservative Jominian thinking which predominated much of the Army, noting that within the army “Mahan’s decrees failed to win universal applause.”[ii] However, Mahan influenced many future leaders of both the Union and Confederate armies in his “Napoleon Club” a military round table at West Point.[iii] Hagerman notes that Mahan’s greatest contributions were his development of the active defense and emphasis on victory through maneuver. Unlike Jomini, who thought maneuver as risky with the purpose of the “defeat of the enemy’s army,” Mahan emphasized “maneuver to occupy the enemy’s territory or strategic points.”[iv] In the book Hagerman wrestles with disjointed developments in infantry, artillery and cavalry tactics of the ante-bellum Army which and surmises that “Military thinking, and even more strategic organization, remained essentially within the Napoleonic tradition filtered through an eighteenth-century world view….” He asserts that “A broader vision was necessary to pose an alternative to the mechanistic program.”[v]

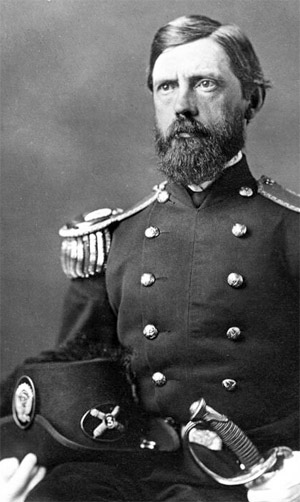

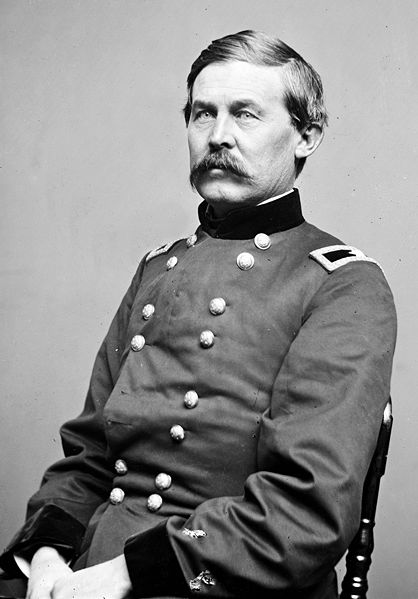

The 2nd Michigan Regiment: Most Civil War Units on both sides were State Regiments

The 2nd Michigan Regiment: Most Civil War Units on both sides were State Regiments

Hagerman then discusses wartime developments in strategy, tactics and organization as they developed in both the Eastern and Western theaters. He focuses on the themes of organization, logistics, communications, weaponry, field fortifications and maneuver. In each chapter he weaves these themes to show how they affected campaigns or were modified during the war based on experience. He deals with leadership, but mostly in the context of how leaders responded to challenges posed in these arenas. Of particular interest to him are the early efforts of successive commanders of the Army of the Potomac including McClellan, Burnside and Hooker to deal with these problems as well as the responses of Grant, Sherman and Rosecrans in the West to the same issues.

Hagerman’s discussion of army organization focuses on how each army developed sociologically as well as professionally prior to and during the war. He examines the ways that commanders educated at West Point initially dealt with large armies made up of militia units and volunteers and how these armies would be changed by the war. He includes in the discussion i the institution of the draft in both the North and South. His discussion of how McClellan successful fought the break-up of the Regular Army keeping it separate from the militia units organized by the States was important to development of the Army. He notes their importance and points out the problems of the militia units raised by the various states particularly in the early part of the war.

The Integration of Sea and Land Logistics Systems in the Civil War Revolutionized the Way that Modern War is Supplied

The Integration of Sea and Land Logistics Systems in the Civil War Revolutionized the Way that Modern War is Supplied

More significant to Hagerman’s narrative is his emphasis on logistics, and how each Army responded to the challenges of supplying their armies in the field. Hagerman examines how the ante-bellum Army developed its logistic doctrine from the Napoleonic examples and how that doctrine had to be modified in light of the American reality of a less developed continent with far greater distances involved.

Hagerman’s discussion of logistics is quite detailed. He examines topics such as the number of wagons per regiment and how army commanders, modified that number at various points during the war based on their situation. He discusses the development of the “flying column” as a response to the dependency on wagons and basic load of food and ammunition carried by each soldier in order to increase strategic maneuverability. He details the forage requirements for people and animals in each theater of operations and how each army responded to requirement of living off the land for much of their forage requirements and their relative successes and failures in supplying their soldiers in this fashion.

Railways Meant the Ability to Move Troops and Supplies Great Distances very Quickly

Railways Meant the Ability to Move Troops and Supplies Great Distances very Quickly

Hagenman discusses the use of railroads and the use of naval forces to both assist the ground forces and to move supplies and troops. In each of these areas he provides a detailed examination of the effect of logistical considerations on each army. He notes that of all the areas of development that the Army of the Potomac was successful at putting logistic theory into practice. By late 1863 the Army of the Potomac demonstrated “the close integration of operational planning and that of the general in chief and supply bureaus. In this one area, the development of a mature and modern staff was evident.”[vi]

Hagerman’s discussion of the development of communications in both armies focuses on the fact that the size of the armies and the distances involved on the battlefield made command and control difficult. As such each army experimented with signals organizations that used tradition visual signals and couriers but began to rely on the telegraph for rapid communications. He deals with the conflict in the North between the Signal Corps and the Military Telegraph Service. He discusses the use of wire telegraph equipment and the new Beardslee wireless telegraphs by the Signal Corps and how the Army eventually favored the traditional wire bound networks operated by the Military Telegraph. Though the Army rejected the Beardslee equipment some commanders requested it for their operations.[vii] As they became more dependent on such communications armies feared that their signals could be compromised through wire tapping and made efforts to encode transmissions.

Signal Corps Soldiers and Wire Communications

Signal Corps Soldiers and Wire Communications

Hagerman’s discusses the evolution of the Union and Confederate armies use of field fortifications including their use in offensive campaigns. He discusses their use by McClellan on the Peninsula in 1861 and Lee’s sporadic use of them[viii] until 1864 beginning in the Wilderness campaign and culminating in the defense and siege of Petersburg. Hagerman’s thesis is that the developments in field works and firepower gave the advantage to the defense when armies made the frontal attacks which were at the heart of Jominian theory. He notes how various commanders including Grant failed at Shiloh and Lee at Antietam failed to dig in, but how both the Union and Confederate armies learned to dig hasty field works as a matter of course.[ix]

Both sides also learned to use maneuver in combination with positional warfare to force the enemy to battle. Hagerman examines the campaigns in the West of Grant, Sherman and Rosecrans, particularly Stone’s River, the Vicksburg Campaign, and the campaign in middle Tennessee.[x] The last two chapters mention these issues in the context of the 1864-65 campaign around Richmond and Sherman’s campaigns in Georgia and the Carolinas. Of particular note is how Sherman’s forces routinely entrenched on the offensive[xi] and how Confederate forces under Joseph Johnston employed entrenchments on the defensive. Hagerman notes how Confederate Cavalry “perhaps best displayed the growing intensity of trench warfare” noting General Joe Wheeler’s use of them at the close of the war.[xii]

Massive Siege Mortar outside Petersburg

Massive Siege Mortar outside Petersburg

A sidebar to Hagerman’s discussion of fortification is his examination of the Corps of Engineers. He discusses the development of Engineering or Pioneer units from nothing in 1861 to organized units by the middle of the war. He examines the problems of the Engineering Corps in adjusting to the war. He notes its dispersion among the line and its civil duties as impediments to responding to the needs of war and both the hesitancy and resistance to creating engineering units by Congress, despite the pleas of McClellan and Lincoln.[xiii] He then looks at the institutional irony of the how newly organized engineer units had few West Point trained Corps of Engineers officers, but were primarily staffed and commanded by officers detailed from the line. The effect was a “decline in the antebellum definition of professionalism embodied in the Corps of Engineers.”[xiv]

Engineering Units were Built from Scratch and Accomplished Many Feats

Engineering Units were Built from Scratch and Accomplished Many Feats

Petersburg Fortifications a Harbinger of World War One

Petersburg Fortifications a Harbinger of World War One

Hagerman’s last two chapters focus on the developments in the strategies of attrition and exhaustion in relation to positional and maneuver warfare. He examines how this was by Grant in Virginia and Sherman in Georgia and the Carolinas. He discusses the “ascendancy of positional warfare” which allowed Lee to hold out and force Grant into winter quarters at Petersburg.[xv] This demonstrated that “an army fighting on interior lines, even under nearly overwhelming conditions of deprivation and against vastly superior numbers, could sustain a prolonged existence by use of field fortification and defensive maneuver.”[xvi] Sherman’s campaign demonstrated how an army could exploit “diversion, dispersion, and surprise to successfully pursue a modern total-war strategy of exhaustion against the enemy’s resources, communications and will.”[xvii]

Sherman’s March to the Sea

Sherman’s March to the Sea

Hagerman’s book is particularly strong in the discussion of tactical developments and logistics and how those were developed over the course of the war. It is strong because it allows the serious student to trace the developments in each of the areas he examines to future wars fought by the US Army. Russell Weigley picks up the effect of what Hagerman describes in his books The American Way of War discussing both Grant’s strategy of annihilation and its costs, and in Sherman’s campaign against Johnston and attack upon Southern resources.[xviii] His discussion of tactics reflects that of J.F.C. Fuller notes that “the tactics of this war were not discovered through reflection, but through trial and error.”[xix] The events described by Hagerman, especially the campaigns of Grant and Sherman influence modern strategy including that of the Marine Corps which discusses maneuver and attrition warfare continuum in MCDP 1 Warfighting.[xx] Hagerman’s work is best at helping tie the elements of war often ignored by other Civil War historians into a coherent whole that allows the reader to see the logical development of each of these elements in modern war.

Irregular Formations Such as Mosby’s Raiders Would Create Problems Behind Union Lines

Irregular Formations Such as Mosby’s Raiders Would Create Problems Behind Union Lines

Hagerman’s value to the literature is that he fills a void among many Civil War writers who often focus simply on the battles and campaigns and not arcane but important subjects such as transportation, logistics, communications and fortifications. Hagerman makes an astute observation on how change comes to military organizations at the end of his discussion of the Corps of Engineers and the Army following the war. He notes “that change in war requires time for digestion before lessons are converted-if they are converted-into theory and doctrine.” [xxi] In the light of the Pershing’s strategy in the First World War One, which revisited some of the worst mistakes of the Civil War one wonders if those lessons were ever fully digested by the Army. Such an observation can be made about our present war. We need to ask if the lessons of previous insurgencies in conquered areas have been digested, even going back to the lessons of the Union Army operating in the hostile lands of the conquered Confederacy.[xxii] Likewise how an Army adjusts to developments in weaponry, technology and tactics are fair game when one analyzes past campaigns in relation to current wars. Thus when we look at Hagerman it is important to use his work to understand the timeless aspects of military history, theory, doctrinal development, logistics, communications and experiential learning in war that are with us even today.

[i] Hagerman, Edward.

The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare. Midland Book Editions, Indiana University Press. Bloomington IN. 1992. p.9

[ii] Ibid. p.13.

[iii] Hagerman also notes the contributions of Henry Halleck and his Elements of Military Art and Science published in 1846 (p.14) and his influence on many American Officers. Weigley in his essay in Peter Paret’s Makers of Modern Strategy would disagree with Hagerman who notes that in Halleck’s own words that his work was a “compendium of contemporary ideas, with no attempt at originality.” (p.14) Weigley taking exception gives credit to Halleck for “his efforts to deal in his own book with particularly American military issues.” Paret, Peter editor. Makers of Modern Strategy: For Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1986 p.416.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid. p.27.

[vi] Ibid. p.79.

[vii] Ibid. p.87.

[viii] The most notable use of them between the Peninsula campaign and the Wilderness was at Fredericksburg by Longstreet’s Corps. Many wonder why Lee failed to entrench at Antietam.

[ix] Fuller, J.F.C. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1957. Fuller comments “Thus over a year of bitter fighting was necessary to open the eyes of both sides to the fact that the trench was a by product of the rifle bullet, and like so many by-products, as valuable as the product itself.” (p.269) He calls it “astonishing that Lee, an engineering officer, made no use of entrenchments at the battle of Antietam.” (pp.269-270)

[x] Ibid. pp. 198-219.

[xi] Ibid. p.295. Hagerman comments how Sherman’s troops outside Atlanta began to entrench both the front and rear of their positions.

[xii] Ibid. p.297-298.

[xiii] Ibid. p.238.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid. p.272

[xvi] Ibid. p.274.

[xvii] Ibid. p.293. B.H. Liddell-Hart in comparing the campaigns of Grant and Sherman makes an important note that Sherman’s strategy is more “suited to the psychology of a democracy…” and “ he who pays the piper calls the tune, and that strategists might be better paid in kind if they attuned their strategy, so far as rightly possible, to the popular ear.” Liddell-Hart, B.H. Strategy Faber and Faber Ltd, London 1954 and 1967, Signet Edition, The New American Library, New York 1974 p.132

[xviii] Weigley, Russell F. The American Way of War: A History of United States Military History and Policy University of Indiana Press, Bloomington IN, 1973. pp.145-146.

[xix] Ibid. Fuller. P.269 A similar comment might be made of most wars including the current Iraq war.

[xx] ___________. MCDP-1 Warfighting. United States Marine Corps, Washington D.C. 1997. pp. 36-39

[xxi] Ibid. Hagerman. P.239

[xxii] Ibid. Fuller. Fuller’s comments on the situation of the Northern Soldier are eerily similar to our current conflict in Iraq : “Consequently, minor tactics were definitely against the Northern soldier, because his major tactics demanded the offensive; for without the offensive the South could not be brought to heel. It was the problem which had faced the French in LaVendee and in the Peninsula of Spain, which faced Napoleon in Russia, and the British in South Africa during the Boer War of 1899-1902. Not only was the Northern soldier, through force of circumstances, compelled to fight in the enemy’s country, but he was compelled to devastate it as well as conquer it, in order to protect himself against the bands of irregular troops which were here, there and everywhere.” pp.247-248

Bibliography

Fuller, J.F.C. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1957

Hagerman, Edward. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare. Midland Book Editions, Indiana University Press. Bloomington IN. 1992

Liddell-Hart, B.H. Strategy Faber and Faber Ltd, London 1954 and 1967, Signet Edition, The New American Library, New York 1974

Paret, Peter editor. Makers of Modern Strategy: For Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1986

Weigley, Russell F. The American Way of War: A History of United States Military History and Policy University of Indiana Press, Bloomington IN, 1973

___________. MCDP-1 Warfighting. United States Marine Corps, Washington D.C. 1997