Despite the warnings of Johnston Pettigrew, Major General Harry Heth with the approval and blessing of his corps commander Lieutenant General A.P. Hill arose on the morning of July 1st 1863 and formed his division for its march to Gettysburg. But it was an inauspicious start to a very bad day for Heth and his division. Somehow orders had not gotten to his units to begin the advance at 5 a.m. and “there was haste to the early morning’s preparations that caught some off guard” even regimental commanders. [1]

During the night Of June 30th 1863 the actions of A.P. Hill show a commander who confused and uncertain. The confidence that he and Heth showed in rejecting Pettigrew and Young’s reports of Federal troops in Gettysburg left “most, if not all the commanding officers in Hill’s corps…unprepared for what happened.” [2] Lieutenant Lewis Young wrote “I doubt if any of the commanders of brigades, except General Pettigrew, believed that we were marching to battle, a weakness on their part which rendered them unprepared for what was about to happen.” [3]

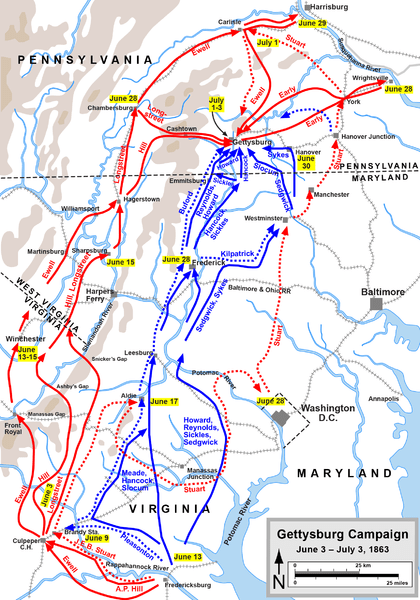

Hill sent a message to Ewell of Second Corps telling that officer that “I intended to advance the next morning and discover what was in my front” [4] and sent word of Pettigrew’s discovery of Union cavalry to Lee’s headquarters, but his warning apparently gave Lee little cause for concern. Porter Alexander noted that on the night of June 30th that he visited Lee’s headquarters and found conversation to be “unusually careless & jolly. Certainly there was no premonition that the next morning was to open a great battle of the campaign.” [5] Hill also sent a courier to Anderson instructing him to bring up his division on Jul 1st and instructed Heth that “Pender’s division also would be ordered through Cashtown as a reserve to be available if Heth ran into serious trouble.” [6]

Since a reconnaissance is normally conducted by small elements, the fact that Hill committed his two divisions present to such a mission demonstrated his confusion of both the nature of what he might face and to the intentions of Robert E. Lee. One has to remember that Lee, like his corps commanders was operating blind, in part due to Stuart’s absence but also due to the poor employment of the cavalry that should have been available to them. Hill and Heth had no idea what they faced at Gettysburg and disregarded the warnings of his own people. Thus it is hard to believe that Hill did not expect the possibility of action. Likewise it is distinctly possible that Heth, despite his orders “may have had more on his mind than shoes and information when he made his advance towards Gettysburg.” [7]

Several critics have made this point, among them Major John Mosby the Confederate cavalry leader and guerrilla fighter who wrote: “Hill and Heth in their reports, to save themselves from censure, call the first day’s action a reconnaissance; this is all an afterthought….They wanted to conceal their responsibility for the defeat.” [8] A more contemporary writer, Jennings Wise noted that Hill’s orders “were specific not to bring on an action, but his thirst for battle was unquenchable, and…he rushed on, and…took the control of the situation out of the hands of his commander-in-chief.” [9] Heth in later years made an unsubstantiated claim that “A courier came from Gen. Lee, with a dispatch ordering me to get those shoes even if I encountered some resistance.” [10] That appears unlikely as Mosby noted that no one ordered Hill to advance and Lee “would never have sanctioned it.” [11] Neither Lee or any of his staff collaborate Heth’s claim and the judicious Porter Alexander who had been in Lee’s headquarters the night of June 30th wrote that “Hill’s movement to Gettysburg was made on his own accord, and with knowledge that he would find the enemy’s cavalry in possession.” [12]

The advance to contact was marred by Heth’s inexperience compounded by the illness of A.P. Hill who on the morning of July 1st had “awakened feeling very ill, too sick to mount his horse…although no diagnosis was made, he was probably suffering from overstrained nerves.” [13] Hill’s absence left Heth, an inexperienced division commander “without any sage counsel” [14] and Heth began to commit a series of costly errors. Heth understood from Hill that his mission was a job that normally would be assigned to cavalry: “to ascertain what force was at Gettysburg, and if he found infantry opposed to him, to report the fact immediately, without forcing an engagement.” [15]

Heth advanced without the caution of a commander who had been told that enemy forces were likely opposing him. Even though he disbelieved the reports some amount of judicious caution should have been indicated. Instead, for reasons unknown Heth had his men advance as if they were conducting a routine movement. He led his advance with his assigned artillery battalion commanded by Major William Pegram. He followed with Archer’s veteran but depleted brigade and Davis’s inexperienced brigade. To compound Davis’s situation that commander led his movement with his new and untested regiments the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina leaving his veteran regiments the 2nd and 11th Mississippi in the rear guarding army stores. [16] It was a curious order of march for it left Johnston’s Pettigrew’s brigade behind both Archer and Davis’s brigades despite the fact that it was closer to Gettysburg than any other brigade and had recent eyes on contact with the enemy and knew the ground and what was ahead of them. Pettigrew’s brigade was followed by Colonel John Brockenbrough’s Virginia brigade. It is hard to know why Heth did this but one can speculate that it might have been because of Pettigrew’s insistence of the type of Federal forces in their front the previous day which caused Heth to do this.

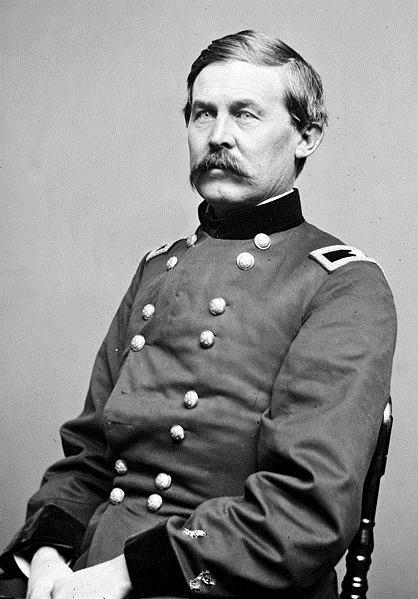

Buford and His Staff

As Heth’s troops advanced to Marsh Creek they encountered the cavalry videttes or pickets of the 8th Illinois Cavalry posted on the high ground just east of the creek. [17] The discovery of these forces was unanticipated by the Confederates leading the column. One of Pegram’s gunners recalled: “We moved forward leisurely smoking and chatting as we rode along, not dreaming of the proximity of the enemy.” [18] Most assumed that the movement “was simply one more part of the army’s concentration of forces” and Brockenbrough told the commander of the 55th Virginia that “we might meet some of Ewell’s command or Stuarts.” [19] Pettigrew had attempted to warn Archer prior to the march of the topography of the area and “a certain road which the Yankees might use to hit his flank, and the dangers of McPherson’s Ridge. Archer listened, believed not, marched on unprepared…” [20] Heth, who should have better anticipated the situation based on Pettigrew’s reports of the previous day demonstrated why one author called him “an intellectual lightweight.” [21] Heth told an officer from the Army of the Potomac after the war “I did not know any of your people were north of the Potomac.” [22]

If Heth was inexperienced and knew little of the Federal forces arrayed before him and what forces were moving towards Gettysburg, his opponent, Brigadier General John Buford was his opposite in nearly every respect. Buford was born in Kentucky and came from a long line of family who had fought in both the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. He was an 1848 graduate of West Point who was commissioned in the Dragoons but too late to serve in Mexico. Instead he served on the Great Plains against the Sioux and on peacekeeping duty in the bitterly divided State if Kansas. Later he served in the Utah War in 1858. His family held Southern sympathies; his father was a Democrat who had opposed Abraham Lincoln.

At the beginning of the war, the governor of Kentucky offered Buford a commission in that states’ militia. At the time Kentucky was still an “undeclared border slave state” and Buford loyal to his oath refused and wrote later “I sent him word that I was a Captain in the United States Army and I intend to remain one.” [23] However his southern ties kept him from field command until the politically well connected by ill-fated, Major General John Pope “could unreservedly vouch for his loyalty wrangled for him command of a brigade of cavalry.” [24] After Pope’s defeat at Second Bull Run in August 1862 Buford returned to staff duties until January 1863 when he was again given a brigade.

Buford was passed over by Hooker for command of the new cavalry corps in favor of Alfred Pleasanton who was eleven days his senior when Hooker reorganized the army before Chancellorsville. In later years Hooker agreed that Buford “would have been a better man for the position of chief” [25] for the Cavalry Corps, but in retrospect Buford’s passover for corps command was good fortune for the Army of the Potomac on June 30th and July 1st 1863. Despite being passed over, Buford a consummate professional, fought well at Brandy Station for which he was recommended for promotion and command of his division. [26]

On the night of June 30th Buford prepared for battle. Unlike Hill and Heth he understood exactly what he was facing. He met with “reliable men” most likely from the Bureau of Military Intelligence operated by David McConaughy as to the composition of Lee’s forces. [27] Buford knew his business; he took the time to reconnoiter the ridges west of Gettysburg and posted videttes as far was as Marsh Creek. He deployed one brigade under Colonel Thomas Devin to the north and west of the town, Colonel William Gamble’s brigade was deployed to the west, its main line being on McPherson’s ridge. Buford planned “a defense in depth, fighting his men dismounted, using the series of ridgelines west of Gettysburg to hamper and delay the Rebel infantry he was certain would come “booming along” the Chambersburg Pike in the morning.” [28]

Noting that the ground was favorable to defense and giving battle Buford sent messages to Reynolds as to the situation. He warned Reynolds that “A.P. Hill’s corps is massed just back of Cashtown, about 9 miles from this place.” He also noted the location of Confederate pickets only four miles west of Gettysburg.” [29] Devin’s troops also identified elements of Ewell’s corps north of the town. Buford had accurately informed his superiors of what was before him, information that they needed for the day of battle.

According to his signals officer, Buford spent the night “anxious, more so than I ever saw him” [30] He discussed the situation with Devin who did not believe that the Confederates would move on Gettysburg in the morning. Devin thought if there were any threats that “he could handle anything that could come up in the next 24 hours.” [31] Buford rejected Devin’s argument and told him “No you won’t…. They will attack you in the morning and they will come booming – skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own.” [32]

Reynolds, seeing the importance of the position elected to fight. He “ordered Buford to hold onto it to the last” believing that if Buford could “buy enough time, he might get his infantry into line “before the enemy should seize the point.” [33]

As Archer and Davis’s troops advanced in the early hours of July 1st their march was uneventful until they reached Marsh Creek. There they encountered the men of the 8th Illinois, one of whom, Lieutenant Marcellus Jones, took a carbine from one of his sergeants saying “Hold on George, give me the honor of opening this ball” and at about 7:30 a.m. Jones fired the first shot of the battle of Gettysburg. [34]

Heth had wanted to advance in column as long as possible “but the Yankee cavalry’s stiff resistance had ended that hope.” [35] Heth rode forward and ordered Archer and Davis’s troops to advance skirmishers with the support of Pegram’s artillery. This slowed the Confederate advance considerably. Heth wrote in his after action report that “it became evident that there were infantry, cavalry and artillery in and around the town.” [36] But instead of “feeling out the enemy” as directed by Hill, Heth “ordered Archer and Davis “to move forward and occupy the town.” [37] A chaplain in Brockenbrough’s brigade reported that one of Heth’s aide’s came up and reported “General Heth is ordered to move on Gettysburg, and fight or not as he wishes.” The chaplain heard one of the officers near him say “We must fight them; no division general will turn back with such orders.” [38]

The fight that Harry Heth and A.P. Hill had been directed not to precipitate was now on. Heth’s inexperience more than matched by the cunning and brilliant Buford, whose troopers now fought a masterful delaying action which enabled Reynolds to come up.

Notes

[1] Tredeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.153

[2] Coddinton, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command A Touchstone Book, Simon and Shuster New York 1968 p.264

[3] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p.51

[4] Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg: A.P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell in a Difficult Debut in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.44

[5] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.264

[6] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 pp. 92

[7] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.274

[8] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.32

[9] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.32

[10] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.153

[11] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.32

[12] Alexander, Edward Porter Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative 1907 republished 2013 by Pickle Partners Publishing, Amazon Kindle Edition location 7342 of 12968

[13] Dowdy.Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation pp.91-92

[14] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.153

[15] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.131

[16] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.156

[17] Pfanz. Gettysburg: The First Day p.53

[18] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p. 162

[19] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.134

[20] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.264

[21] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.134

[22] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 162

[23] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[24] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[25] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.44

[26] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.64

[27] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.141

[28] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 157

[29] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.122

[30] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 157

[31] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.266

[32] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.123

[33] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.122-123

[34] Pfanz. Gettysburg: The First Day p.53

[35] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 163

[36] Luvaas, Jay and Nelson Harold W editors. The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg South Mountain Press, Carlisle PA 1986 p.7

[37] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 165

[38] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.163