Friends of Padre Steve’s World

As I now clear the decks to try to finish “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory” tonight I present another section of one of my Gettysburg draft manuscripts. Today is a look at the leaders of Lieutenant General A.P. Hill’s Third Corps.

Have a great night

Peace

Padre Steve+

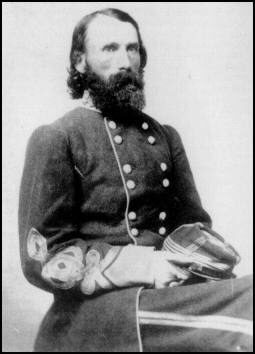

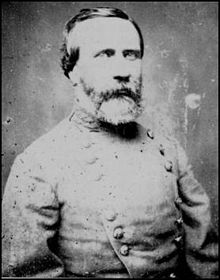

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell “A.P.” Hill, C.S.A.

As I mentioned before the problem of where to find leaders for the Corps, Divisions, and Brigades of the Army of Northern Virginia was a serious issue for Robert E. Lee. He was bent on invading the North in June, despite the risks, and despite the lack of preparation of iThis Army under the new leaders he had appointed. With the death of Stonewall Jackson, he split Jackson’s Second Corps, taking two divisions from it and one from Longstreet’s First Corps to built Third Corps.

The newly created Third Corps under Lieutenant General A.P. Hill was thought to be in good hands. Hill had commanded his large; six brigade “Light Division” with distinction, though having serious conflicts with both Longstreet and Jackson. At Antietam Hill’s hard marching from Harpers Ferry which allowed the Light Division to arrive on the battlefield in a nick of time, had saved the Army of Northern Virginia from destruction.

Hill was a graduate of West Point, class of 1847. He would have been part of the illustrious class of 1846, but the young cadet had a certain proclivity for women and a certain amount of debauchery lost a year of study after contracting “a case of gonorrhea, followed by complications, which were followed by lingering prostatitis” [1] afflictions which caused many other ailments that would plague him the rest of his life. At West Point Hill roomed with and became a longtime friend of a refined cadet from Philadelphia, George McClellan. His delayed graduate put him in the class of 1847 where along with his roommate Julian McAllister and friends Harry Heth and Ambrose Burnside were the social leaders of the class, due to their “practical jokes and boisterous conduct.” [2]

Hill graduated fifteenth in his class and was assigned to the artillery. The young Second Lieutenant accompanied Brigadier General Joseph Lane’s brigade to Mexico where he saw limited action at the end of the war and mainly served on occupation duty. In Mexico and in the following years he was stricken with various fevers including typhoid and yellow fever, as well as recurrences of his prostatitis which so limited his ability to serve in the field with the artillery that he requested a transfer to a desk job. This he was granted by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis who detailed him “for special duty in the United States Coast Survey offices in Washington D.C.” [3]

The assignment to the Coast Survey offices was unusual, especially for Hill’s era of service, for they were a part of the Department of the Navy. Despite much political support, Hill could not get promoted to captain, likely due to the fact that he was working for the Navy. As war drew near Hill married Kitty Morgan McClung. His friends at the Coastal Survey attempted to convince him to remain with the Union as serving in their office he would have little chance of taking up arms against Virginia.

Hill was torn, he hated slavery and the depreciations visited on blacks; having in 1850 responded to the lynching of a young black man in his home town of Lynchburg: “Shame, shame upon you all, good citizens…Virginia must crawl unless you vindicate good order or discipline and hang every son of a bitch connected with this outrage.” [4] Likewise he was not in favor of secession, but he, like so many other Southern officers felt a stronger connection to family and his Virginia heritage than to the Union, and resigned his commission on February 26th 1861.

Hill was appointed as a Colonel of infantry in May 1861 to organize and command the 13th Virginia Infantry regiment. He commanded the regiment in the Valley and western Virginia as well as at First Manassas. By February 1862 he was a Brigadier General commanding Longstreet’s old Virginia brigade on the Peninsula where he distinguished himself against McClellan at Williamsburg. On May 26th 1862 he was promoted to Major General and given command of the very large so called “Light Division.” He emerged from the fighting on the Peninsula, the battles around Richmond and the Seven Days “with the reputation of being one of the best combat officers that Lee had.” [5] However, his success on the battlefield, like so many commanders came at great cost. In those battles his division suffered nearly 5,500 casualties. “Six colonels and three majors were killed; two brigadiers (Anderson and Pender), eleven colonels and six lieutenant colonels wounded.” [6]

Hill had an earned reputation as a brilliant division commander with the Light Division. Despite his clashes with Longstreet, and especially with Jackson, who had Hill arrested twice and attempted to have him court-martialed, Lee recommended him to take command of Third Corps. Lee sang his praise of Hill and his abilities to Jefferson Davis noting that Hill was “the best soldier of his grade with me.” [7] However, Hill had never commanded more than one division in action, except for the confused hour after Jackson had been struck down. Hill, however, was devoted, prompt, and energetic, and deserved promotion.” [8]

Hill’s reputation as a superb division commander was well earned, at Antietam where when Lee’s army was in danger of destruction, he “drove his men at a killing pace toward the sound of distant gunfire….” [9] Hill’s “Light Division’s remarkable march from Harper’s Ferry- seventeen miles in less than eight hours- rivaled the best marks by Jackson’s famous foot cavalry.” [10] Upon his arrival “instantly recognized the military situation, Kyd Douglas wrote, “and without waiting for the rest of the division and without a breathing spell he threw his columns into line and moved against the enemy, taking no note of their numbers.”[11] Hill’s march saved the Army of Northern Virginia from destruction as he dealt reverses to his old friends McClellan and Burnside. “Lee’s reference to him in his official Sharpsburg report, “And then A.P. Hill came up,” had become a byword in the army.” [12] There were other times, notably at Second Manassas and Fredericksburg where “he was sometimes careless on the battlefield,” and in both instances “his defensive postings were poor and nearly proved very costly.” [13]

Hill was a “nervous wiry man with a persistent chip of underappreciation on his shoulders and a bevy of chronic illnesses when under stress.” [14] He had an “impetuous streak and fiery temperament that matched his red beard, traits that at times had brought him trouble on the battlefield and off…” [15] He Despite that Hill exhibited a fondness and care for the welfare of his men that earned their respect and admiration. One officer called him “the most loveable of all Lee’s generals,” while “his manner so courteous as almost to lack decision.” [16]

Hill detested Jackson, who he referred to as “that old Presbyterian fool.” [17] His poor relations with Jackson’s confidants at Second Corps ensured that Ewell took Second Corps when Lee reorganized the army after Chancellorsville.

Lee appointed Hill to command Third Corps of which “half of the troops had been with him all along” [18] in the Light Division. Lee liked Hill’s aggressiveness and command instincts, which mirrored his own. Lee hoped that Hill’s aggressive instincts as a division commander would translate into success at the corps level. As such Lee, promoted him over the heads of D.H. Hill and Lafayette McLaws who were both senior to him. Longstreet was not in favor of Hill’s appointment, most likely due to his altercation with Hill the previous year and lobbied for the promotion of D.H. Hill.

Regarding the promotion of A.P. Hill and Ewell, Lee wrote to Davis:

“I wish to take advantage of every circumstance to inspire and encourage…the officers and men to believe that their labors are appreciated, and that when vacancies occur that they will receive the advantages of promotion….I do not know where to get better men than those I have named.” [19]

But the decision to promote the Ewell and Hill, both Virginians stirred some dissent among those that believed that Lee was “favoring Virginians over officers from other states. The promotion of A.P. Hill, as previous noted was “made over the head of two Major Generals more senior than Hill- North Carolinian D.H. Hill and Georgian Lafayette McLaws.” [20] There is some validity to this perception, as Longstreet’s biographer Jeffry Wert noted:

“While the bulk of the troops hailed from outside the Old Dominion, two of the three corps commanders, six of the ten division commanders – including Jeb Stuart with the cavalry – and sixteen of forty-seven brigade commanders were natives of Virginia, along with the army commander and the chief of artillery.” [21]

Hill’s corps, like those of Longstreet and Ewell was composed of three divisions, and even more so than Ewell his division suffered a want of senior leaders who had served at the grade they were now expected to serve.

Anderson’s Division

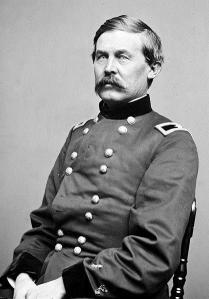

Major General Richard Anderson, C.S.A.

The most stable division in Third Corps was Richard Anderson’s, transferred from First Corps. Under Longstreet the division and its commander had served well. Anderson was an 1842 graduate of West Point and classmate of Longstreet and Lafayette McLaws. He served in the Dragoons on the frontier, in Mexico and again on the frontier, throughout the 1840s and 1850s. He was promoted to Captain in 1855 and stationed in Nebraska when his home state of South Carolina seceded from the Union.

“Tall, strong, and of fine background, Anderson never was disposed to quibble over authority or to indulge in any kind of boastfulness.” [22] He began the war commanding the 1st South Carolina Infantry, and was soon a brigadier. He fought well on the Peninsula and was promoted to Major General and given command of Benjamin Huger’s former division in July of 1862. He commanded the division at Second Manassas and at Antietam, where he was wounded in the vicious fighting at the Bloody Lane. The division saw little action at Fredericksburg, but in “the Battle of Chancellorsville, he and his men fought extremely well.” [23] Lee commented that at Chancellorsville that Anderson was “distinguished for the promptness, courage, and skill with which he and his division executed every order.” [24]

Lee considered Anderson a “capable officer”…and had marked him for future higher command.” [25] Anderson was noted for his modesty and unselfishness, “his easy going ways, combined with his competence and professionalism made him one of the most well liked officers in the Army of Northern Virginia.” [26]

However, there was an incalculable thrown into the equation. During the reorganization of the army, Anderson’s division was detached from Longstreet’s First Corps and assigned to Hill’s new Third Corps. Hill had not yet established his methods of operation as a corps commander, and Anderson, used to “Longstreet’s methodical insistence that everything be just so before he would venture into action” contrasted with Hill’s “tendency to leap before he looked.” [27]

Anderson’s division was composed of five brigades commanded by a mixed lot of commanders, only one of whom was a professionals soldier.

Wilcox

Brigadier General Cadmus Wilcox was a no-nonsense graduate of the illustrious West Point class of 1846. Hailing from Tennessee, Wilcox was outgoing and popular, and before the end of his first year “had made friends of every member of the class. It was said that no cadet of his time had so many friends and was so universally esteemed.” [28] He kept those friends throughout the years, friends who remained his friends, even though they had to fight against him. Harry Heth said of him “I know of no man of rank who participated in our unfortunate struggle on the Southern side, who had more warm and sincere friends, North and South.” [29]

Wilcox graduated near the bottom of the class fifty-fourth of fifty-eight and was commissioned as an infantry officer. Wilcox served in the Mexican War where he was in the thick of the fight at Chapultepec, on the frontier, and taught tactics for five years at West Point. Following that assignment he studied for two years in Europe. Wilcox is an expert rifleman and instructor. He “wrote a manual, Rifle and Infantry Tactics, and translated an Austrian manual on infantry tactics.” [30]

When war came he resigned his commission and became Colonel of the 9thAlabama Infantry, and by October 1861 he was promoted to Brigadier General and given command of a brigade. He had served with distinction as a brigade commander at Williamsburg, Seven Pines and the Seven Days Battles, and was given acting command of small division at Second Manassas. However, after an uneven performance he is passed over for command of a division which instead was given to his classmate, George Pickett. Wilcox was disgruntled and upset at being “passed over for advancement in favor of a junior officer.” [31] “Restless, sore, and disposed to go to another Confederate army where he will have a chance,” [32] Wilcox asked Lee for a transfer to another army, but “Lee could not afford to lose such an experienced brigadier, and refused to transfer” him. [33]

At Chancellorsville the delaying action of his brigade at Salem’s Church had helped save the army. Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps had succeeded in crossing the Rappahannock and was marching on Lee’s rear areas. On May third with the fate of the army in the balance, Wilcox “reasoned intelligently and promptly when he should leave Banks’ Ford. Then, instead of joining Early, he took his chance on being destroyed in order that he might delay the enemy on the Plank Road.” [34]Wilcox and his troops, supported by other units of McLaws’ division which came up in support thrashed the Union troops, inflicting 1523 casualties for the loss of 674 men. [35] In his post-battle report Lee noted that Wilcox was “entitled to especial praise for the judgment and bravery displayed “in impeding Sedgwick “and for the gallant and successful stand at Salem’s Church.” [36] Three months later he will get his promotion to Major General and command of a division.

Mahone

Brigadier General William “Little Billy” Mahone was a diminutive graduate of VMI with no prior military experience.. Barely five foot five inches tall and weighing just 125 pounds the brigadier was described by Moxie Sorrel as “Very small in height and frame, he seemed a mere atom with little flesh.” [37] There was so little substance to his body that when his wife heard that he had “he had taken a flesh wound at Second Manassas…she knew it had to be serious, she said, “for William has no flesh whatsoever.” [38]

Instead Mahone was an engineer who had “established himself as a resourceful construction engineer for railroads.” [39] When Virginia seceded he was “president, chief engineer and superintendent of the new Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad, which he succeeded in constructing across the bottomless Dismal Swamp.” [40] Hard driven, he had dreams of connecting his railroad with others and linking the Virginia Tidewater with the Mississippi and the Pacific.

Mahone was an ardent secessionist and when Virginia seceded he took leave of his railroad and became Colonel of the 6th Virginia Infantry, with which he occupied Norfolk when Federal forces evacuated it. He was soon a brigadier and his skill in engineering was put to good use at Drewry’s Bluff before Richmond.

He commanded his brigade with reasonable effectiveness before Gettysburg. As a brigadier “he is not lacking in diligence, but he is not without special distinction.”[41] As a brigade commander fought competently at Chancellorsville and by Gettysburg had established himself as a “competent and experienced brigade leader.” [42] His actions at Gettysburg would be controversial, but he rose to fame as the war went on and became one of the hardest fighting division commanders in the Army of Northern Virginia during the Wilderness, Petersburg and to the end of the war where he “one of Lee’s most conspicuous – and trusted – subordinates.” [43]. Following the war Mahone expands the Norfolk and Western Railway system, and entered politics, where won election as a Republican to the U.S. Senate in 1880.

Wright

Brigadier General Ransom “Rans” Wright was a Georgia lawyer who had grown up dirt poor and between hard work and study had made a name for himself. He was a “very gifted man, a powerful writer, an effective orator, and a rare lawyer.” [44]

He had strong Unionist sentiments, something that gained him little popularity in a secession minded state, he was the brother in law of Stephen Douglas’s running mate Herschel Johnson and supported the pro-Union ticket of John Bell and Edward Everett.

Despite his sentiments Wright volunteered when Georgia seceded and despite his lack of military experience was named Colonel of the 3rd Georgia Infantry. He took command of his brigade as a Colonel and was promoted to Brigadier General in June 1862. By the time of Gettysburg he “was considered a well-tested combat veteran.” [45] Despite his earned reputation as a solid brigade commander, Wright “did not endear himself to the Virginia elite in the Army of Northern Virginia.” [46]In 1864 the Governor of Georgia requested that he be detached from the Army of Northern Virginia to serve in that state where he was promoted to Major General.

Posey

Brigadier General Carnot Posey was a highly successful plantation planter and lawyer who had served as a “lieutenant under Col. Jefferson Davis, and suffered a slight wound at the Battle of Buena Vista” [47] in the Mexican War. After the war he returned to his legal practice and was appointed as a United States District Attorney by President Buchanan, a position that he held until Mississippi seceded from the Union. At the outset of the war he organized a company named the “Wilkinson Rifles.” That company became part of the 16th Mississippi Infantry and Posey became its first Colonel. He was badly wounded at Cross Keys in the Valley campaign.

He fought well at Second Manassas and took acting command of Featherston’s brigade at Antietam. Despite a poor showing there by the brigade which collapsed in confusion after doomed counter-attack on the Sunken Road, he was promoted to brigade command prior to Chancellorsville where he and his brigade gave a strong performance under fire. He was mortally wounded at Bristoe Station on October 14th 1863.

Lang

Colonel David Lang commanded the Florida Brigade, the smallest Brigade in the army. Just twenty-five years old, the graduate of the Georgia Military Institute inherited brigade command when Brigadier General Edward Perry came down with typhoid fever after Chancellorsville. He had only fought in three battles, two as a captain “and he had never led a brigade in combat.” [48] After Gettysburg when Perry returned to the brigade Lang returned to command his regiment, finally taking command of a brigade at Petersburg at the end of the war, without a promotion to Brigadier General.

Pender’s Division

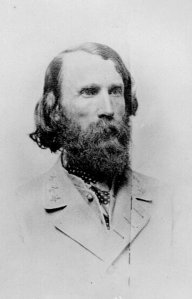

Major General Dorsey Pender, C.S.A

Hill’s old Light Division was divided into two divisions. Major General William Dorsey Pender commanded the old Light Division which now consisted of four rather than six brigades.

Pender was a “pious, serious North Carolinian” [49]and a graduate of West Point when he graduated nineteenth of forty-six in that class. Prior to the war he served on the frontier and in California with the artillery and dragoons. During the secession crisis he “offered his services to the Confederacy even before most of the states, including his own, had seceded.” [50]

Pender was “only seven years out of West Point” [51] in 1863 when he was promoted to Major General and given command of his division, he was only twenty-nine years old, and the “youngest of that rank in the army.” [52] The young general was deeply loyal to Powell Hill and a partisan of the Light Division. However, he had risen “on first rate ability, steadfast ambition and a headlong personal leadership in battle which gave a driving force to his brigade” [53] which he considered “the best brigade of the best division” [54] in the army.

Lee praised him as “a most gallant officer” and was deeply sensitive about keeping Pender with the troops that found him so inspiring noting “I fear the effect upon men of passing him over in favour of another not so identified with them.” [55]Pender was an “intelligent, reflective man, deeply religious and guided by a strong sense of duty.” [56]

Pender’s four veteran brigades were commanded by three experienced officers and one new to brigade command, but the young general would not get to lead them into action for long as he was mortally wounded by a shell fragment before the division was to go into action on July 2nd at Gettysburg. His division would be led by Brigadier General James Lane on July 2nd and turned over to Major General Isaac Trimble shortly before Pickett’s Charge.

Perrin

Colonel Abner Perrin from South Carolina was the least experienced of Pender’s brigade commanders. He had prior Regular Army experience. He enlisted in the army at the age of nineteen and served as a lieutenant in Mexico. He resigned his commission in 1848 and became a successful lawyer. When secession came he volunteered and served as a company commander in the 14th South Carolina. Perrin took command of the regiment after Fredericksburg. He led the regiment in action for the first time at Chancellorsville. Lee named him to command the brigade when his brigade commander, Samuel McGowan, was wounded. He was not promoted to Brigadier General, but despite his inexperience he remained in command of the veteran South Carolina brigade, “whose leadership had been decimated” and had “devolved to lieutenant colonels, majors and captains.” [57]His brigade performed well on the first day, and his leadership earned him his promotion. He was killed in action in the “counterattack at the Bloody Angle at the Battle of Spotsylvania on May 12th, 1864. Just before the battle he promised to emerge a live major general or a dead brigadier.” [58]

Lane

Brigadier General James Lane was an academic. He graduated second in his class at VMI in 1854 and received a degree in science from the University of Virginia three years later. He returned to VMI as an assistant professor then became a professor of natural philosophy at the North Carolina Military Institute. [59]

He led many of his cadets to war when he was commissioned as a major in the 1stNorth Carolina Volunteer Infantry. He took command of it in September 1861 and was promoted to brigade command in October 1862 after Antietam.

Lane proved himself an able commander at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. During the Battle of Chancellorsville his brigade led Jackson’s assault against the Union right, suffering 909 casualties. That night he had the misfortune to be part of one of the saddest episodes of the Confederate war when one of his units mortally wounded Stonewall Jackson on the night of May 2nd 1863. Despite this “he and his men could be counted on to do the right thing when the bullets started to fly.” [60] He was badly wounded at Cold Harbor and missed most of the rest of the war. Following the war he returned to academics and was a professor of civil engineering at the Alabama Polytechnic Institute when he died in 1907.

Thomas

Brigadier General Edward Thomas was a plantation owner from Georgia. He was not completely without military experience having served as a lieutenant of Georgia mounted volunteers in the Mexican War. He was offered a commission in the Regular Army after the war, but he turned it down and returned home.

He became colonel of the 35th Georgia Infantry in October 1861 and led it as part of Pettigrew’s brigade. When Pettigrew was wounded at Seven Pines the regiment was shifted to Joseph Anderson’s brigade of the Light Division. Thomas assumed command of that brigade when Anderson was wounded at Frayser’s Farm and returned to Richmond to “resume direction of the important Tredegar Iron Works.” [61] He commanded it in the thick of the fighting at Second Manassas, and at Fredericksburg helped stop Meade’s advance with a fierce counterattack. He continued to command it at Chancellorsville. Thomas could always be counted on to deliver “a solid, if unspectacular performance.” [62] He remained in command of the brigade through the end of the war and surrendered with Lee at Appomattox.

Scales

Brigadier General Alfred Scales was new to brigade command. A “forty-five year old humorless politician…a duty driven public official-turned-warrior.” [63]Scales had served in the U.S. House of Representatives and left politics when the war began. Since he had no military experience he chose, unlike so many other men of stature, to enlist as a private when North Carolina seceded.

His fellow soldiers elected to a captaincy in Pender’s 3rd North Carolina Volunteers. When Pender was transferred, Scales succeeded him in command of the regiment. He commanded that regiment on the Peninsula and during the Seven Days. From that time Scales’ career was “one of consistent stout service in Pender’s hard fighting brigade.” [64] Scales served as acting commander of the brigade when Pender was wounded at Fredericksburg and “met the test.” [65] He distinguished himself with the 13th at Chancellorsville where he was wounded in the thigh. Scales service with Pender’s brigade “had been one of consistent stout service.” [66]

When Pender was promoted to division command “it was a forgone conclusion that his replacement in brigade command would be Scales.” [67] He had served with the brigade, was known to its soldiers and though inexperienced as a brigade commander he “and the brigade were one, for he had shared its fortunes, was proud of it, and was confident of victory as he led it to Gettysburg.” [68]

Heth’s Division

Major General Harry Heth, C.S.A.

Hill’s remaining division was commanded by the newly minted Major General Harry Heth. It was composed of the two remaining brigades of the Light Division and two brigades that had recently joined to the army for the offensive.

Harry Heth was a graduate of West Point who had a “high reputation personally and professionally.” [69] He was a cousin of George Pickett and joined Pickett as one of the hell raising cadets of the academy. Their reunion at the academy “developed into a three-year effort to see how much illicit merriment they could initiate without getting booted out.” [70] Heth graduated no higher in his class than Pickett did his the previous year, finishing at the bottom in the forty-five member class of 1847. Heth wrote of his West Point years later admitting that his academic record was

“abominable. My thoughts ran in the channel of fun. How to get to Benny Havens occupied more of my time than Legendre on Calculus. The time given to study was measured by the amount of time necessary to be given to prevent failure at the annual examinations.” [71]

Heth spent fourteen years in the old army, rising to the rank of Captain and spending most of his time on the frontier. Heth came from a family with long ties dating back to the American Revolution where his grandfather had, fought and the War of 1812 where his father had served. He was “well liked for his social graces, and Powell Hill held him in great respect.” [72]

Lee had a high regard for Heth who “had a solid record as Lee’s quartermaster general in the early days of Virginia’s mobilization for war.” [73] Lee considered him a friend and somewhat a protégé, however his regard “cannot be based on any substantive achievements by Heth, whose antebellum career and war experience had been similarly unremarkable.” [74] The appointment would prove to be a mistake. “Heth had little experience under fire, and an earlier petition for Heth’s promotion had been turned down by the Confederate Senate.” [75] When he recommended Heth for command of the new division he assured Jefferson Davis that he had “a high estimate of Genl. Heth.” [76] Heth did know his own deficiencies and candidly “admitted his own weaknesses and resisted the temptation to take himself too seriously.” [77]

Clifford Dowdy wrote that Heth was an example of a “soundly trained soldier of perennial promise. Always seemingly on the verge of becoming truly outstanding”but “never lived up to the army’s expectations.” [78] Heth became a brigade commander in Hill’s division prior to Chancellorsville after having served in Western Virginia and in the West.

Heth was new to command of the newly formed division which was a hastily put together force. In a new division where experienced leadership was needed, Heth had the weakest collection of brigade commanders in the Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg. Ironically, it would be the division that stumbled into combat against the Buford’s Cavalry and Reynold’s First Corps at Herr, McPherson and Seminary Ridge on July 1st 1863. After Gettysburg he retained command of his division “with steadfastness and some competence until the final surrender.” [79]

Pettigrew

Newest to the division was Brigadier General Johnston Pettigrew whose North Carolina brigade was one of the largest in the army. This was one of the new brigades provided to Lee by Davis, and “it had no appreciable experience.” [80]Pettigrew was a renaissance man, “the most educated of all Confederate generals.” [81] He was a graduate of the University of North Carolina. He was “proficient in French, German, Italian and Spanish, with a reading knowledge of Greek, Hebrew and Arabic.” [82]

Pettigrew had spent a good amount of time abroad on diplomatic service before returning to his law practice in Charleston. He had “even spent time as a volunteer aid with the French and Italian forces against the Austrians in 1859.” [83] He was elected to the state legislature in 1856 when he “sensed the oncoming of hostilities and was named colonel of the 1st Regiment of Rifles, a Charleston militia outfit.” [84] Pettigrew was “one of those natural leaders of a privileged background who, without military ambitions, had been advanced on the application of native intelligence and contagious courage.” [85]

Davis

Brigadier General Joseph Davis, the nephew of President Jefferson Davis commanded a newly raised Mississippi brigade. Davis was “a congenial and conscientious officer,” but “he had never led troops in battle.”[86] Davis owed his appointment to his relationship with the President. He was “entirely without combat experience.” [87] Robert Krick wrote that Davis’s “promotion to the rank of brigadier general seems to be as unadulterated an instance of nepotism as the record of the Confederacy offers.” [88] Davis survived Gettysburg and after a bout with typhoid fever returned to command his brigade and “served solidly, though unspectacularly, until the end of the war with Lee’s army.” [89]

Most of the war he had been spent on his uncle’s staff in Richmond and in his new appointment he was not with officers of any experience as “No one serving on Joe Davis’s staff showed strong signs of having the background, experience, and ability that might help the brigadier meet his responsibilities.” [90] Likewise the nine field grade officers assigned to the regiments of his brigade were similarly ill-equipped for what they would face in their first test of combat.

Archer

Heth did have the experienced mixed Alabama-Tennessee brigade of Brigadier General James Archer under his command, but despite its experience and “fine reputation” [91] the brigade was seriously understrength after seeing heavy combat at Chancellorsville.

The brigade commander James Archer was a native of Bel Air Maryland, one of two Maryland officers serving in the Army of Northern Virginia. Archer was graduate of the University of Maryland who practiced law before entering the Regular army as a Captain during the Mexican War. During the war he was brevetted for gallantry at the Battle of Chapultepec. He left the army after the war and then returned to it in 1855 as an infantry Captain and was serving in Walla Walla Washington as the secession crisis deepened.

He resigned his commission in March 1861 and was commissioned in the new Confederate army. He received command of the 5th Texas Regiment “who thought him a tyrant.” [92] Though he had no battle experience he was promoted to Brigadier General and took command of a Tennessee brigade at Seven Pines when its commander was killed. Like the Texans the Tennesseans did not take to him and dubbed him “The Little Game Cock.” [93]

Initially, Archer was not well liked in any of his commands, the Texans considered him a tyrant and he was “very non-communicative, the bearing and extreme reserve of the old army officer made him, for a time, one of the most hated of men.”[94] After being joined to the Light Division Archer transformed his reputation among his men and had “won the hearts of his men by his wonderful judgment and conduct on the field.” [95] He distinguished himself at Antietam, and though quite ill led his brigade solidly. At Fredericksburg Archer helped save the Confederate line by leading a counter-attack following the Union breakthrough at Telegraph Hill.

Brockenbrough

The last brigade of Heth’s division was the small Virginia brigade of the “plodding, uninspiring” [96] Colonel John Brockenbrough. Brockenbrough was a “wealthy, but rough- looking Virginia planter.” [97] He was an 1850 graduate of VMI.

He entered “entered service as colonel of the 40th [Virginia Infantry] in May 1861.” [98] The brigade when it had been commanded by Charles Field had been considered one of the best in the army. Brockenbrough took command of it in 1862 when Field was wounded, but he “had never managed the brigade well, especially at Fredericksburg, and Lee returned him to regimental command.” [99]

Brockenbrough again assumed the command of the brigade after Chancellorsville when Heth was promoted. Lee did not deem him suited for promotion, but believed that Brockenbrough “could be counted on to keep together a command sadly reduced in numbers.” [100] Like Archer’s brigade the brigade was “sadly reduced in numbers” and in morale…” [101] His performance at Gettysburg was dreadful and five days after the battle Lee relived him of command of the brigade, returning to his regiment with lower ranking subordinate in command of the brigade. He resigned from the army in 1864.

Hill’s Third Corps was the least prepared command to go into battle at Gettysburg. While some leaders, particularly Richard Anderson, Dorsey Pender and Cadmus Wilcox were excellent commanders, the corps was led by too many untried, inexperienced, or in some cases incompetent leaders to be committed to an offensive campaign so shortly after it was constituted. Likewise, some of its formations were just shells of what they had been before Chancellorsville and had not been reconstituted

Notes

[1] Waugh, John C. The Class of 1846: From West Point to Appomattox, Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan and their Brothers Ballantine Books, New York 1994 p.166

[2] Robertson, James I. Jr. General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior Random House, New York 1987 p.13

[3] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.26

[4] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.22

[5] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.95

[6] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.95

[7] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.526

[8] Ibid. Freeman Lee p.304

[9] Ibid. Robertson, General A.P. Hillp.143

[10] Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1983 p.285

[11] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.144

[12] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.301

[13] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.45

[14] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.22

[15] Ibid. Sears Landscape Turned Red p.285

[16] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.301

[17] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.22

[18] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to MeridianRandom House, New York 1963 p.434

[19] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.526

[20] Ibid. Taylor, John Duty Faithfully Performed p.290

[21] Ibid. Wert General James Longstreet p.249

[22] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.108

[23] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.343

[24] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.512

[25] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.86

[26] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.306

[27] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg pp.86-87

[28] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.69

[29] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.498

[30] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.310

[31] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.310

[32] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.46

[33] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.310

[34] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.512

[35] Sears, Stephen W. Chancellorsville Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 1996 p.385

[36] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.512

[37] Trudeau, Noah Andre, The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864-April 1865 Little Brown and Company, Boston, Toronto, London 1991 p.117

[38] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.55

[39] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.243

[40] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.314

[41] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.48

[42] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.315

[43] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.243

[44] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.328

[45] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.317

[46] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.328

[47] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.319

[48] ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.322

[49] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.23

[50] ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.325

[51] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.85

[52] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.47

[53] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.85

[54] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.45

[55] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.47

[56] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.85

[57] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.331

[58] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.332

[59] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg pp.332-333

[60] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.334

[61] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.282

[62] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.337

[63] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.338-339

[64] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.421

[65] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.421

[66] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.421

[67] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.338

[68] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.306

[69] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.46

[70] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.13

[71] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.13

[72] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.88

[73] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.178

[74] Ibid. Krick, Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: p.96

[75] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.23

[76] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.47

[77] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.178

[78] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.87

[79] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.342

[80] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.50

[81] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.196

[82] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.343

[83] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.129

[84] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.343

[85] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.78

[86] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.196

[87] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.553

[88] Krick, Robert K. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day of Gettysburg in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992

[89] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.354

[90] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.101

[91] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.87

[92] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.349

[93] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.350

[94] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.349

[95] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.350

[96] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.55

[97] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.134

[98] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.118

[99] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.134

[100] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.529

[101] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.134