Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

It has been a very long day. My legs hurt, I broke the big toe on my right foot Thursday afternoon, and between real work and work at home I put on about 7.5 miles on my legs. Thankfully I used Mr. Cane, who came into my life when I broke my tib-fib near the knee back in 2011 was there to help me out. I showed up at command PT dressed out in my PT uniform with Mr. Cane, but it was not the “Cane Mutiny.” Yes, that is a very bad pun, but when your are as tired as I am and in as much pain you really don’t care, but I digress…

I still am working on my article about the President’s terrible week which seems to get more fascinating by the hour. Maybe after a long day working in the house tomorrow, ripping out nasty old carpet. laying some flooring in closets, and doing a bunch of other stuff I might try to finish it tomorrow, which is actually today because I am still awake and it is after midnight.

So what the hell, tonight I am reposting a section of my unpublished Civil War book A Great War in a Revolutionary Age of Change. This section continues one that I posted two or three weeks ago dealing with U.S. Army artillery. This particular section deals with the period between 1846 and the summer of 1864. It is as non-partisan as you can get, but I hate to admit that the thought of M-1857 12 Pound smoothbore “Napoleons” firing at massed Confederate infantry in the open as they did during Pickett’s Charge does warm my heart. Oh my God it almost gives me a woody, but that isn’t exactly very Christian of me, but as I readily admit I am no saint and pretty much a Mendoza Line Christian. At least I can admit it.

So have a great day and please get some sleep.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

American artillery doctrine subordinated the artillery to the infantry. Doctrine dictated that on the offensive “was for about one-third of the guns to occupy the enemy’s artillery and two-thirds to fire on the infantry and cavalry. Jomini liked the concentrated offensive cannonade where a breach of the line was to be attempted.” [1] But being such a small service, it was difficult for Americans to actually implement Napoleonic practices, or organization as the organization itself “was rooted in pre-Napoleonic practice, operating as uncoordinated batteries.” [2]

American artillerymen of the Mexican War could not match the massive firepower and concentration of Napoleon’s army. Instead it utilized mobile tactics, which gave it “the opportunity to maneuver in open country to support the infantry.” [3] During the war the actions of the highly mobile light batteries proved decisive, as did the spirit of their officers and soldiers. The Americans may not have had the organization of Napoleon, but “the audacious spirit was there.” [4] In a number of engagements American batteries employed the artillery rush, even gaining the admiration of Mahan, a noted exponent of the defensive. Among the leaders of the artillery at the Battle of Buena Vista were Captain Braxton Bragg, and Lieutenants John Reynolds and George Thomas, all of who would go on to fame in the Civil War. During a moment when Mexican forces threatened to overwhelm the American line, Bragg’s battery arrived:

“Without support, Bragg whirled his guns into battery only a few rods from the enemy…. The Mississippi Rifles and Lane’s Hoosiers also double-quicked from the rear of the plateau. From then on it was a storybook finish for the Americans, and artillery made the difference. Seventeen guns swept the Mexicans with grape and canister…. Reynolds, Thomas, and the others stood to the work with their captains until 5 o’clock. Santa Ana was through…” [5]

At Casa Mata outside of Mexico City, Americans found their flank threatened by Mexican cavalry. Captain James Hunter and Lieutenant Henry Hunt observed the situation and “Without awaiting orders they rushed their guns to the threatened sector… With Duncan directing them, all stood their posts long enough to spray the front ranks of mounted Mexicans with canister, the shotgun effect of which shredded the half-formed attack columns, dissolving all alignment and sending the lancers scrambling rearward in chaos…” [6] As a result these and other similar instances the artillery came out of the war with a sterling reputation and recognition of their gallant spirit. John Gibbon reflected such a spirit when he wrote: “Batteries derive all their value from the courage and skill of the gunners; from their constancy and devotion on difficult marches; from the quickness and capacity of the officers; and especially from the good condition and vigor of the teams, without which nothing can be undertaken.” [7]

At the beginning of the war U.S. Army doctrine recommended placing batteries equally across the line and concentrating them as needed. The last manual on artillery tactics Instruction for Field Artillery, published in 1859 retained much of its pre-Mexican War content and the doctrine in it provided that artillery was to “be organized at the regiment and brigade level with no reserve.” [8] Nonetheless some artillery officers discussed the possibilities of concentration, Grand Batteries, and the artillery reserve, no changes in organization occurred before the war. However, these discussions were all theoretical, as practical experience of these officers was limited to the small number of weapons employed in the Mexican War, and the “immediate problem was the organization of an unaccustomed mass of artillery.” [9] The Artillerist’s Manual, a highly technical treatise on gunnery was written by Captain John Gibbon in 1859 while he was serving at West Point and used by artillerymen of both sides during the war. In Gibbon described the principle object of the artillery was to, “sustain the troops in the attack and defense, to facilitate their movements and to oppose the enemy’s; to destroy his forces as well as the obstacles that protect them; and to keep up the combat until the opportunity for a decisive blow.” [10]

Since the United States Army traditionally drawn their doctrine from the French this meant going back to the Napoleonic model the foundational unit of which was the battery. The field artillery batteries were classed as either foot artillery or horse artillery. The horse artillery accompanied the cavalry and all gun crews went into battle mounted as cavalrymen. The soldiers of the foot artillery either rode with the guns or walked. The battery was the basic unit for American artillery and at the “start of the war the artillery of both sides was split into self-contained batteries, and each battery allocated to a particular brigade, regiment or even battalion of infantry.” [11]

At the battery level Union artillery was organized by type into six-gun batteries. Confederate artillery units were organized into four or six-gun batteries in which the guns were often of mixed type. This often led to supply problems for Confederate gunners and inconsistent rates of fire and or range. Confederate gunners also had to deal with poor quality power and explosive shells, a condition that only worsened as the war continued. The well-trained Union gunners had better quality ammunition and gunpowder as well as what seemed to the Confederates to have limitless ammunition.

Each gun was manned by a seven-man crew and transported by a team of horses that towed a limber, which transported the cannon and a caisson, which transported the ammunition. The caissons would normally be stocked with four chests of ammunition. For a Napoleon “a standard chest consisted of twelve shot, twelve spherical case, four shells, and four canister rounds for a total of 112 rounds of long range ammunition.” [12] In addition to the ammunition carried in the caissons of each gun, more ammunition was carried in the corps and division supply trains.

As the war progressed the both the Union and Confederate armies reorganized their field artillery. In the North this was a particular problem due to the lack of flexibility and politics in the Army which were prejudiced against large artillery formations, despite the great numbers of batteries and artillerymen now in the army. However the Federal army had good artillerymen. The Regular Army batteries were the foundation of the artillery service. Unlike the infantry units which were overwhelmingly composed of volunteer soldiers, the artillerymen were regulars, many who had served for years in the ante-bellum army.

Since there were few billets for senior artillerymen many artillery officers volunteered or were selected to serve in the infantry to get promoted or to take advantage of their experience and seniority. One of those chose was John Reynolds who promote to Lieutenant Colonel and given orders to form an infantry regiment. Before he could get started in that work he was made a Brigadier General of Volunteers. He wrote: “I would, of course, have preferred the Artillery arm of service, but could not refuse the promotion offered me under any circumstance, much less at this time, when the Government has a right to my services in any capacity.” [13] Other artillerymen who rose to prominence outside of the branch during the war included William Tecumseh Sherman, George Meade, John Gibbon, George Thomas, Ambrose Burnside, and Abner Doubleday, and Confederates Stonewall Jackson, Braxton Bragg, Jubal Early, and A.P. Hill.

However, General Winfield Scott took action to keep a core of experienced artillery officers with the artillery. At Scott’s behest, “the War Department limited the resignations of artillerymen to accept higher rank in infantry regiments, resulting in a core of capable and experienced officers.” [14] This allowed George McClellan to select two exceptional artillery veterans, William Barry and Harry Hunt to “organize the branch and to oversee training.” [15] McClellan appointed Barry, who had been commissioned in 1836 as the head of his artillery. After the defeat at Bull Run, Barry “prepared as set of guidelines or principles for the artillery service. He prescribed a uniform caliber of guns in each battery, four to six cannon in each battery, and that four batteries – one Regular Army and three volunteer – be attached to each division.” [16] In this organization, McClellan and Barry “called for the Regular Army battery commander to take charge of those batteries assigned to the division. This was in addition to his responsibilities to his own battery.” The practical effect of this was that “with the exception of the Artillery Reserve, the highest artillery command remained that of a Captain.” [17]

Hunt was responsible for the organization of the Artillery Reserve and the siege train. The Artillery Reserve was given eighteen batteries, about 100 guns or about one-third of the army’s artillery. It would be a source from which to replace and reinforce batteries on the line, but Hunt also understood its tactical employment. He explained:

‘In marches near the enemy it is often desirable to occupy positions with guns for special purposes: the command fords, to cover the throwing and taking up bridges, and for other purposes for which it would be inconvenient and unadvisable to withdraw their batteries from the troops. Hence the necessary reserve of artillery.” [18]

Hunt’s Artillery Reserve would be of great value in the early battles of maneuver. “The primary advantage of the army artillery reserve was the flexibility it gave the commander, making it unnecessary to go through the division or corps commanders. The reserve batteries could be used whenever or wherever needed.” [19] But this would not be in the offense role that Napoleon used his artillery to smash his opponents, for technology and terrain would seldom allow it; but rather in the defense; especially at the battles of Malvern Hill and Gettysburg. However, “Gettysburg was the last battle of the Civil War in which field artillery fire was paramount…” but “By the end of 1863, the tide of war had changed in the eastern theater, with both sides making more use of field fortifications to cover themselves from the murderous fire of the infantry rifle.” [20]

Even so, lack of promotion opportunity for artillerymen was a problem for both sides during the war, and artillerymen who showed great promise were sometimes promoted and sent to other branches of service. A prime example of such a policy was Captain Stephen Weed “who fought his guns brilliantly in the first two years of the war, and a Chancellorsville even commanded the artillery of a whole army corps.” Henry Hunt “singled him out as having a particular flair for handling large masses of cannon, and wanted to see him promoted.” [21] He was promoted to Brigadier General but in the infantry where he would lead a brigade and die helping to defend Little Round Top. In all “twenty-one field-grade artillery officers in the Regular Army became generals in the Volunteers, but only two remained with the artillery branch.” [22]

Both Barry and Hunt sought to rectify this issue. Barry insisted that a “battery of artillery was the equivalent of a battalion of infantry” [23] and pressed for a higher grade structure for the artillery. Colonel Charles Wainwright wrote of their efforts: “Many officers of the regular artillery have long been trying to get a recognition of their arm of the service, doing away with the regiments and making a corps of it, the same as the engineers and ordnance. McClellan and Hunt drew up a plan soon after Antietam, which by Stanton and Halleck, but nothing more has been hear of it.” [24]

However, Barry and Hunt were opposed by War Department insiders. General Lorenzo Thomas, the Adjutant General used law and regulation to prevent promotions in the artillery beyond Captain and as to General Officers as well. Thomas insisted that the battery was equivalent of an infantry company or cavalry troop. He noted “that laws long in force stipulated that only one general officer could be appointed per each for each forty infantry companies or cavalry troops.” [25] He applied this logic to the artillery as well, which meant in the case of the Army of the Potomac which had over sixty batteries that only one general could be appointed. The result could be seen in the organization of the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg, the artillery component, “which included approximately 8,000 men with 372 pieces – almost the manpower (and certainly the firepower) of a complete army corps. It included only two general officers… then there were three colonels and no other high ranks at all. One army corps had its guns commanded by a lieutenant.” [26] Over time the situation would improve and the artillery given some autonomy within the Army, at Gettysburg Meade gave Hunt command authority to employ the artillery as he deemed necessary, even over the objections of the corps commanders.

General Henry Hunt was probably the most instrumental officer when it came to reorganizing Union artillery organizations in the Army of the Potomac. Following the Battle of Chancellorsville, Hunt prevailed upon the army commander, Joseph Hooker to create “artillery brigades assigned to each corps. This overcame a problem at Chancellorsville, where the batteries of uncommitted divisions had gone unused. The reorganization also made a practical adjustment to the situation where the attrition of divisions was making the corps the basic tactical unit.” [27] In the reorganization the infantry brigades retained their assigned batteries for direct support, but the guns of the divisions were organized into brigades at the corps level. The artillery brigades of the infantry corps had “from four to eight batteries, depending on the size of the corps.” [28] Despite being reflagged as brigades the command structure was not increased. This was often due to the fact “that for much of the war commanding officers persisted in regarding artillery as merely a subsidiary technical branch, an auxiliary which might add a little extra vitality to a firing line if conditions were favourable – but more typically would not.” [29] Dr. Vardell Nesmith noted:

“Resistance within the Army to formalizing tactical organizations for field artillery above the level of the battery was a complex phenomenon. Certainly there was some hesitance on the part of the Army establishment to create new organizations that would come between infantry and cavalry commanders and their fire support assets. Also one cannot discount the institutionalized tendency to keep everyone in their proper place – in other words, to keep a new power group from organizing.” [30]

Organized into brigades the Artillery Reserve became the instrument of the Army commander and served as what we would now call “general support”artillery where they were invaluable to Union army commanders to be available to augment other batteries and to replace batteries which had suffered casualties while on line. The organization of the artillery into brigades, even if they were field expedient organizations did much to increase the effectiveness of the arm. They supplanted “the battery in tactics and to considerable degree in administration. Supply and maintenance were improved, and more efficient employment and promptness and facility of movement resulted. In addition, the concentration of batteries was favorable for instruction, discipline, and firepower. Fewer guns were needed, and in 1864, the number of recommended field pieces per 1,000 men was reduced from 3 to 2.5.” [31]

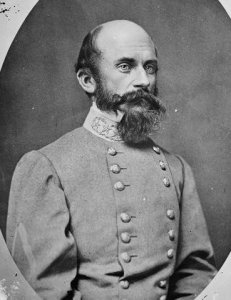

General Henry Hunt

Hunt lobbied the War Department to provide a staff for each brigade, but since the new units were improvised formations no staffs were created and no promotions authorized for their commanders. Colonel Wainwright proposed a congressional bill to organizer volunteer artillery units into a corps of artillery, but lamented:

“Both Barry and General Hunt while commanding the artillery of this army have frequently complained in their reports of the great want of field officers. Were the light batteries of each state organized as a corps, and provided with field officers in the proportion proposed in the bill referred to above, this want would be provided for. The officers of light batteries also have a claim demanding some such change. No class of officers in our volunteer service stand as high as high as those of our light batteries. I say without hesitation that they are very far superior as a class in all respects to the officers of the infantry or cavalry. Yet for them there is not a chance at this time any chance of promotion above a simple captaincy, except in the few light regiments spoken of. I can point to several cases of captains of light batteries who, from this want of field officers, have for the past year exercised all the authority and borne all the responsibility of a brigadier-general.” [32]

But change did come, however slowly and with great resistance from the War Department bureaucracy, and the artillery service “did succeed in winning some measure of recognition for its independent status and tactics. After Gettysburg the army’s artillery commander was accept as having overriding authority in gunnery matters, with the infantry relegated to a merely consulting role, although in practice the change brought little improvement.” [33] The beginning of this came in August 1863 when George Meade promulgated an order that “defined Hunt’s authority in matters of control of the artillery in the Army of the Potomac. The order “definitely stated that Hunt was empowered to supervise and inspect every battery in the army, and in battle to employ them “under the supervision of the major-general commanding.” [34] The order was important but still did not go far enough to remedy the problem of a lack of field officers in the artillery, a problem that was not completely remedied during the war although Ulysses Grant did allow a limited number of promotions to provide more field grade officers in the artillery service of the Army of the Potomac and other armies under his command in the Eastern Theater. Likewise some additional billets were created in the brigades as brigade commanders “were authorized a staff consisting of an adjutant, quartermaster, commissary officer, ordnance officer (an artillery officer on ordnance duty), medical officer, and artillery inspector, with each staff officer having one or more assistants…” However the staff officers had to be detailed from the batteries, thereby reducing the number of officers present with those units”[35] However, in most cases the brigade commanders remained Captains or First Lieutenants.

In the Western theater there was a trend toward the centralization of the artillery in the various armies depending on the commander and the terrain and the size of the operation. As the war progressed in the west commanders began to group their artillery under brigades, divisions, and finally under the various army corps. At Shiloh Grant concentrated about 50 guns “in the notorious “Hornet’s Nest,” perhaps saving him from defeat.” [36] Artillery tactics shifted away from the offense to the defense and even during offensive operations western commanders were quick to entrench both their infantry and artillery. During the Atlanta campaign and march to the sea William Tecumseh Sherman successfully reduced his artillery complement first to 2 guns per 1,000 men then to 1 per 1,000. [37] This was in large part because he was conducting a campaign of maneuver and was far from his logistics base. Since supplies had to be carried with the army itself with a heavy reliance on forage, Sherman recognized that his army had to be trimmed down. Likewise, “the terrain and concept of operations must have been very important in his decision.” His “rapid, almost unopposed raid through Georgia gave no opportunities for the massing of large batteries in grand manner.” [38] During the campaign Sherman marched without a siege train and reinforced his cavalry division with light artillery batteries.

Notes

[1] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.21

[2] Ibid, Bailey Field Artillery and Firepower p.195

[3] Ibid, Bailey Field Artillery and Firepower p.194

[4] Ibid. Nesmith Stagnation and Change in Military Thought: The Evolution of American Field Artillery Doctrine, 1861-1905 – An Example p.6

[5] Nichols, Edward J. Toward Gettysburg: A Biography of General John Reynolds, The Pennsylvania State University Press 1958, reprinted by Old Soldier Book Gaithersburg MD 1987 p.43

[6] Ibid. Longacre The Man Behind the Guns: A Military Biography of General Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery, Army of the Potomac pp.53-54.

[7] Gibbon, John. Artillerist’s Manual: Compiled from Various Sources and Adapted to the Service of the United States. 1859 retrieved from http://www.artilleryreserve.org/Artillerists%20Mannual.pdf 19 January 2017 pp.345-346

[8] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.22

[9] Ibid. Nesmith Stagnation and Change in Military Thought: The Evolution of American Field Artillery Doctrine, 1861-1905 – An Example p.19

[10] Ibid. Gibbon Artillerist’s Manual: Compiled from Various Sources and Adapted to the Service of the United States. p.343

[11] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.165

[12] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 p.15

[13] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg: A Biography of General John Reynoldsp.75

[14] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.39

[15] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac p.39

[16] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac p.40

[17] Ibid. Nesmith Stagnation and Change in Military Thought: The Evolution of American Field Artillery Doctrine, 1861-1905 – An Example pp.21-22

[18] Ibid. Longacre The Man Behind the Guns: A Military Biography of General Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery, Army of the Potomac p.98

[19] Ibid. McKenny The Organizational History of Field Artillery 1775-2003 p.65

[20] Ibid. McKenny The Organizational History of Field Artillery 1775-2003 p.74

[21] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.166

[22] Ibid. McKenny The Organizational History of Field Artillery 1775-2003 p.60

[23] Ibid. Nesmith Stagnation and Change in Military Thought: The Evolution of American Field Artillery Doctrine, 1861-1905 – An Example p.22

[24] Wainwright, Charles S. A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright 1861-1865 edited by Allan Nevins, Da Capo Press, New York 1998 p.336

[25] Ibid. Longacre The Man Behind the Guns: A Military Biography of General Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery, Army of the Potomac p.100

[26] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.166

[27] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.94

[28] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.94

[29] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.166

[30] Ibid. Nesmith Stagnation and Change in Military Thought: The Evolution of American Field Artillery Doctrine, 1861-1905 – An Example pp.22-23

[31] Ibid. McKenny The Organizational History of Field Artillery 1775-2003 p.62

[32] Ibid. Wainwright. A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright 1861-1865 p.337

[33] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.166

[34] Ibid. Longacre The Man Behind the Guns: A Military Biography of General Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery, Army of the Potomac p.181

[35] Ibid. McKenny The Organizational History of Field Artillery 1775-2003 p.61

[36] Ibid, Bailey Field Artillery and Firepower p.198

[37] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.284

[38] Ibid. Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.178