Volksturm Members

Volksturm Members

One of the more important but little understood parts of the German mobilization to defend the Reich, was the creation of the Volksturm. The Volksturm’s role in Nazi strategy and ideology is often misunderstood more than likely because on the Western Front the Volksturm was not much of a factor. Of the major chroniclers of the war in Europe only Max Hastings in “Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 1944-1945” [1] and John Erickson in “The Road to Berlin” [2] devote any attention to the subject. Others, including B.H. Liddell-Hart’s History of the Second World War,” Chester Wilmont’s “The Struggle for Europe” and Russell Weigley’s “Eisenhower’s Lieutenants” devote no space whatsoever to the Volksturm. This is understandable. The Volksturm was far less effective than Nazi leaders would have hoped in fact militarily it was a failure because of the Nazi Party management of it. Even German historian Walter Goerlitz’s “History of the German General Staff” devotes only one small passage to the Volksturm.[3] Other German Generals such as Generals Warlimont and Guderian and Field Marshal Kesselring mention the Volksturm but only Guderian goes into any detail about it.[4] Kesselring mentions its “propaganda value” and calls the Volksturm a “fiasco” [5] while limiting his other comments to specific uses of it. In light of such limited analysis by leading historians David Yelton’s treatment in “Ein Volk Steht Auf”: The German Volksturm and Nazi Strategy, 1944-45 published in The Journal of Military History is highly important.

Volksturm receiving training on Panzerfaust Anti-Tank Rocket

Volksturm receiving training on Panzerfaust Anti-Tank Rocket

Yelton’s study is more than an analysis of military value and use of the Volksturm. The Volksturm was more than a military organization. As a military organization it had many grave deficiencies as do all militias in a State where most able bodied men are already in the regular military components. However, as an arm of the Nazi Party leadership’s defensive strategy to resist the allies, it played a key role. It was a political militia designed for total war effort to defend the Germany against the advancing Allied armies in conjunction with the “miracle weapons” which were just beginning to be deployed. Kesselring notes the propaganda value of the Volksturm, but to understand its place in Nazi strategic thinking, one has to look at the entirety of Nazi political, ideological and military thinking at this point in the war, something that Yelton does well.

Yelton makes an important point regarding Gerhard Weinberg’s assertion that most historians have neglected Germany’s late war strategy and that “Nazi Germany is viewed as having no real, coherent strategy” after 1943.[6] Yelton; like Weinberg shows how Nazi leaders believed in a reversal in the course of the war and how they “began implementing a broad and coherent strategy to this end.”[7] He discusses the influence of Nazi ideological preconceptions which impacted strategy[8] and notes the two primary purposes of the Volksturm were to stalemate the war by making the Allies fight for “every foot of German territory and maximize Allied casualties beyond which their morale…could tolerate” and more importantly from the Nazi viewpoint to “fanaticize the civilian population ….”[9] From this point Yelton goes into a discussion of the beginnings of the Volksturm. He looks first to the mind of General Guderian[10] who advocated forming a militia to be activated when the Soviets threatened German soil. Guderian saw this in military terms. It was to be under Army Wehrkreis or Military District control on the Eastern Front and not civilian control. It was the subsequent political machinations of Bormann, Himmler and others which expanded it to the entire nation, and placed it in the hands of Nazi Party Gauleiters who often were antagonistic to the Army.[11]

An important point is that the shift in control from the Wehrmacht Wehrkreis to Bormann’s Nazi Party control was related to the basic Nazi understanding of war, the understanding that the war was a “struggle for existence.”[12] Likewise it was a tenant of Nazi faith in racial ideology was since the the “Master Race” was being defeated by lesser races it had to be the result of “treason or sabotage in the officer corps.”[13] Thus many of the Reich’s political leaders believed that “the key to victory lay in generating a fanatical will to resist among all Germans both civilians and military.”[14] Of course this created more problems in terms of logistics and command and control for military commanders wherever the Volksturm was directed by the more paranoid of the Gauleiters.

The goal of the Volksturm was to maximize Allied casualties in the hope that one of the Allied nations would decide that the war was senseless and drop out. The Nazis believed that this would take place while the new weapons, jet aircraft and new U-Boats wrested control of the air and sea from the Allies and the V weapons, rockets and missiles brought destruction to Britain. A second goal was to strengthen the political will of the German population. This goal included the political aspects of how the Party extended its influence over the military. The Party gained control of the political indoctrination of recruits, the appointment of National Socialist Leadership Officers and increased roles for Gauleiters in preparing defenses at home and in the military chain of command.[15] Yelton’s study provides a detailed analysis of the psychological conditioning of the Volksturm instituted by Bormann including the use of propaganda and that all Volksturm training should “include some form of National Socialist “schooling.”[16] Bormann ensured that the Volksturm was made up of all components of the “racially superior” Nazi Volksgeimenschaft carefully excluding Jews, other “racially inferior” groups, as well as clergymen who might undermine the people with Christian ideas or were politically divisive or unreliable.[17] Yelton concludes by examining how the Nazi leadership attempted to raise the military value of the Volksturm by appointing Nazis who had military experience as officers. They believed that “the racial superiority of the German Volk would ultimately carry the day against their “inferior Jewish-Bolshevik-Slavic” enemies.[18]

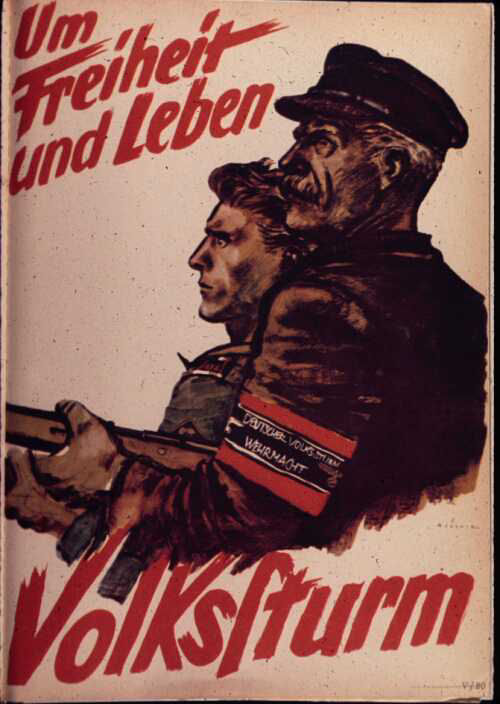

Volksturm Propaganda Poster

Volksturm Propaganda Poster

Yelton’s essay is important to the historian of the late war period to understand how Nazi ideology influenced the German war effort. Yelton does a commendable job in analyzing the Volksturm and its role in Nazi strategy in late 1944-45. He makes very good use of original sources as well as historic works and documents, including diaries and operations orders of Hitler, Himmler and others, correspondence between Bormann and Gauleiters. His use of published and unpublished works dealing with the Volksturm and Nazi ideology, particularly letters and diaries serve as an important source of information about how the closely the Nazis linked ideology to the Volksturm.. Yelton’s conclusions that the Volksturm was a key component of what senior Nazis believed to be a coherent strategy to win the war are convincing. Gerhard Weinberg also posits this view, and it gains credence when one studies other aspects of German racial war theories.

Yelton’s study shows that a more holistic approach to a military history needs to include political, ideological and other factors that lead to the formation of military strategy. In isolation the creation of the Volksturm makes little sense from a purely military point of view and most of the senior officers believed the Volksturm was a waste of manpower and weaponry. However, if the Volksturm is viewed as part of Nazi political and racial theory it made perfect sense to Nazi leaders.

Thus, political ideologies are something to consider when one believes an opponent’s strategy is senseless or militarily suspect. Simply looking at the military side of the equation often leads to wrong answers about the nature of the conflict. This has been the case more often than not in many ongoing conflicts today where religious and political ideology is at the center of the opponent’s resistance. It is understanding idea of the people’s war where the population is mobilized to fight the war even if militarily weak and is often related to defending one’s homeland such as the Taliban in Afghanistan or the Vietnamese who successfully opposed French, Japanese, American and Chinese efforts to subdue them. Thus understanding helps the reader understand how a badly flawed organization can make perfect sense to the leaders employing it. This is something that we in the Western World of the early 21st Century are not very good at doing and are currently failing at doing in Afghanistan. The political or the political-religious ideology that drives people to fight for existence matters as much as the military understanding of the enemy’s strengths and weaknesses. In World War Two Germany had lost most of the capacity to resist effective under the assault of the Allies and the people had become war weary. Thus the Volksturm were doomed to fail. However, had Germany been better organized to meet the Allied threat asymmetrically and not been so militarily defeated conventional sense, the effort of the Volksturm might have brought better results.

[1] Hastings, Max. Armageddon: The Battle for Germany 1944-1945. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY. 2004. Hastings’ discussion does not go into detail on the formation or organization of the Volksturm itself. He focuses more incidental aspects of training and employment as well as people’s feelings toward. He does make the connection between increasing Nazi fanaticism and the Volksturm. p.160

[2] Erickson, John. The Road to Berlin” Cassell Military Paperbacks, London, 1983. Erickson’s best contribution is noting how Martin Bormann and the Party Gauleiters controlled the Volksturm and the turf war that Heinrich Himmler waged to ensure that his Waffen-SS formations would not be deprived of manpower by his erstwhile party comrades. p.399

[3] Goerlitz, Walter. History of the German General Staff,” translated by Brian Battershaw, Westview Press, Boulder and London, 1985. Originally published as Die Deutsche Generalstab Verlag der Frankfurter Hefte, Frankfur am Main, 1953. It is interesting to note that Goerlitz attributes the formation of the Volksturm to Himmler, p.483 something repudiated by General Heinz Guderian and Yelton in this reviewed essay. At the same time it is understandable to see how Goerlitz reaches his conclusion in light of the fact that Himmler had some control as commander of the Replacement Army.

[4] Guderian, Heinz Panzer Leader translated by Constantine Fitzgibbon, Ballantine Books, New York, New York, 1957. p. 288

[5] Kesselring, Albrecht. The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Kesselring. Greenhill Military Paperbacks, London, 1997. Originally published as Soldat bis zum letzen Tag Anthenum, Bonn, 1953 and translated by William Kimber, London 1953. p.73. Kesselring’s comments here come in comparison to the British formation of a Home Guard in 1940. In general Kesselring found these types of units to be worthless and personnel, especially older soldiers brought back on duty with regular units.

[6] Yelton, David K. Ein Volk Steht Auf: The German Volksturm and Nazi Strategy 1944-1945 in The Journal of Military History, October 2000, 64, 4. Research Library p.1061. Although he fits Weinberg’s thesis that the Germans believed that they could still win the war and developed a strategy to do so Weinberg does not mention the Volksturm in his book although it would be easy to extrapolate from his thesis Yelton’s assertion of the Volksturm being a part of that strategy.

[7] Ibid. p.1062.

[8] Ibid. This is important as the understanding of Nazi ideology in many decisions is downplayed by many purely “military” historians.” However, Michael Geyer in his essay German Strategy, 1914-1945 in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, Peter Paret editor, Princeton University Press, 1986 p.582 talks about the rise of political-ideological strategy in Nazi Germany where Hitler “rejected the traditional analysis of military strengths of the opposing sides….” This could be part of the reason of why many military historians fail to distinguish a discernable strategy on the part of the Germans which the Volksturm was a key element. At the same time this ties in with other over arching aspects of the Nazi war effort going to early actions against the Poles and Russians.

[9] Ibid. Yelton. Pp.1063-1064.

[10] Ibid. Yelton. p.1068. The idea was actually that of Guderian’s Chief of Staff’s predecessor General Huesinger in 1943.

[11] Ibid. Yelton pp. 1065-1066. An interesting note to this discussion is Guderian’s comments that “the Party was less interested in the military qualifications than in the political fanaticism of the men that it appointed to fill the responsible posts.” Guderian, Heinz Panzer Leader translated by Constantine Fitzgibbon, Ballantine Books, New York, New York, 1957. p. 288 Guderian’s comments are particularly relevant because he recognized that the political and ideological components of the organization outweighed the military.

[12] Ibid. Yelton p.1067 General Walter Warlimont notes that General Keitel countersigned the order forming the Volksturm with Bormann and that the order “charged the Party with the formation and leadership of this “last levy.” Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-45 translated by R.H. Barry. Presidio Press, Novato CA. 1964. Originally published in Germany under the title Im Hauptquarier der Deutschen Wehrmacht 1939-1945 Bernard und Graefe Verlag. p.479 It is interesting to note that as such this was a political and ideological decision versus a purely military one.

[13] Ibid. Yelton p. 1068

[14] Ibid. Yelton p. 1069

[15] Ibid. Yelton. pp. 1071-1072. Guderian noted how the Gauleiters on the Eastern Front would go directly to Bormann when conflict arose with the Wehrmacht. Panzer Leader p. 289

[16] Ibid. Yelton. p. 1075

[17] Ibid. Yelton pp. 1077-1079

[18] Ibid. Yelton. p.1082