Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

This is another of my continued series of articles pulled from my various Civil War texts dealing with Emancipation and the early attempts to gain civil rights for African Americans. This section that I will cover for the next few days deals with the post-war period, a period marked by conflicting political and social desires for equality, justice, revenge, and the re-victimization of Blacks who had so recently been emancipated.

I hope that you find these helpful.

Peace

Padre Steve+

The Passage of the Fourteenth Amendment

The situation for newly emancipated blacks in the South continued to deteriorate as the governors appointed by President Johnson supervised elections, which elected new governors, and all-white legislatures composed chiefly of former Confederate leaders. Freedom may have been achieved, but the question as to what it meant was still to be decided, “What is freedom?” James A. Garfield later asked. “Is it the bare privilege of not being chained?… If this is all, then freedom is a bitter mockery, a cruel delusion.” [1] The attitude of the newly elected legislatures and the new governors toward emancipated blacks was shown by Mississippi’s new governor, Benjamin G. Humphreys, a former Confederate general who was pardoned by Andrew Johnson in order to take office. In his message to the legislature Humphreys declared:

“Under the pressure of federal bayonets, urged on by the misdirected sympathies of the world, the people of Mississippi have abolished the institution of slavery. The Negro is free, whether we like it or not; we must realize that fact now and forever. To be free does not make him a citizen, or entitle him to social or political equality with the white man.” [2]

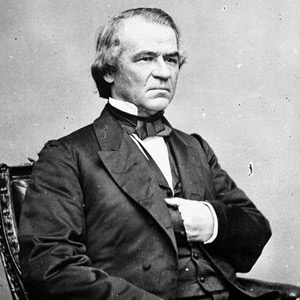

Johnson’s continued defiance of Congress alienated him from the Republican majority who passed legislation over Johnson’s veto to give black men the right to vote and hold office, and to overturn the white only elections which had propelled so many ex-Confederates into political power. Over Johnson’s opposition Congress took power over Reconstruction and “Constitutional amendments were passed, the laws for racial equality were passed, and the black man began to vote and to hold office.” [3] Congress passed measures in 1867 that mandated that the new constitutions written in the South provide for “universal suffrage and for the temporary political disqualification of many ex-Confederates.” [4] As such many of the men elected to office in 1865 were removed from power, including Governor Humphreys who was deposed in 1868.

These measures helped elect bi-racial legislatures in the South, which for the first time enacted a series of progressive reforms including the creation of public schools. “The creation of tax-supported public school systems in every state of the South stood as one of Reconstruction’s most enduring accomplishments.” [5] By 1875 approximately half of all children in the South, white and black were in school. While the public schools were usually segregated and higher education in tradition White colleges was restricted, the thirst for education became a hallmark of free African Americans across the county. In response to discrimination black colleges and universities opened the doors of higher education to many blacks. Sadly, the White Democrat majorities that came to power in Southern states after Reconstruction rapidly defunded the public primary school systems that were created during Reconstruction. Within a few years spending for on public education for white as well black children dropped to abysmal levels, especially for African American children, an imbalance made even worse by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson which codified the separate but equal systems.

They also ratified the Thirteenth and the Fourteenth Amendments, but these governments, composed of Southern Unionists, Northern Republicans and newly freed blacks were “elicited scorn from the former Confederates and from the South’s political class in general.” [6] Seen as an alien presence by most Southerners the Republican governments in the South faced political as well as violent opposition from defiant Southerners.

The Fourteenth Amendment was of particular importance for it overturned the Dred Scott decision, which had denied citizenship to blacks. Johnson opposed the amendment and worked against its passage by campaigning for men who would oppose it in the 1866 elections. His efforts earned him the opposition of former supporters including the influential New York Herald declared that Johnson “forgets that we have passed through a fiery ordeal of a mighty revolution, and the pre-existing order of things is gone and can return no more.” [7]

Johnson signed the Amendment but never recanted his views on the inferiority of non-white races. In his final message to Congress he wrote that even “if a state constitution gave Negroes the right to vote, “it is well-known that a large portion of the electorate in all the States, if not a majority of them, do not believe in or accept the political equality of Indians, Mongolians, or Negroes with the race to which they belong.” [8]

When passed by Congress the amendment was a watershed that would set Constitutional precedent for future laws. These would include giving both women and Native Americans women the right to vote. It would also be used by the Supreme Court in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that ended the use of “separate but equal” and overturned many other Jim Crow laws. It helped lead to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1964 and the Civil Rights Act of 1965, and most recently was the basis of the Supreme Court decision in Obergfell v. Hodges, which give homosexuals the right to marry. Section one of the amendment read:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” [9]

Even so, for most white Southerners “freedom for African Americans was not the same as freedom for whites, as while whites might grant the black man freedom, they had no intention of allowing him the same legal rights as white men.” [10] As soon as planters returned to their lands they “sought to impose on blacks their definition of freedom. In contrast to African Americans’ understanding of freedom as a open ended ideal based on equality and autonomy, white southerners clung to the antebellum view that freedom meant mastery and hierarchy; it was a privilege, not a universal right, a judicial status, not a promise of equality.” [11] In their systematic efforts to deny true freedom for African Americans these Southerners ensured that blacks would remain a lesser order of citizen, enduring poverty, discrimination, segregation and disenfranchisement for the next century.

Ulysses S. Grant and the Fight against the Insurrection, Terrorism and Insurgency of the Ku Klux Klan, White Leagues, White Liners and Red Shirts

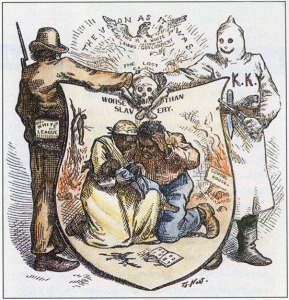

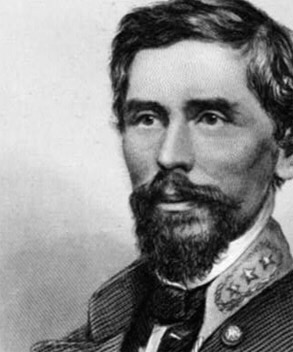

But these measures provoked even more violence from enraged Southerners who formed a variety of violent racist organizations which turned the violence from sporadic attacks to what amounted to a full-fledged insurgency against the new state governments and African Americans. Organizations like the Ku Klux Klan engaged in terroristic violence to heavily armed “social clubs” which operated under the aegis of the state Democratic Party leadership in most Southern states. Under the leadership of former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest whose troops had conducted the Fort Pillow massacre, the Klan’s membership throughout the South “was estimated at five hundred thousand.” [12] The majority of these men were former Confederate soldiers, although they were also joined by those who had not fought in the war, or later those who had been too young to fight in the war but even belatedly wanted to get in on the fight against the hated Yankee and his African American allies. As the shadowy organization grew it became bolder and more violent in its attacks on African Americans, Republican members of the Reconstruction governments, and even Southern Jews. The Klan spread to every State in the South and when Congress investigated in 1870 and 1871 they submitted a thirteen volume report on Klan activities, volumes that “revealed to the country an almost incredible campaign of criminal violence by whites determined to punish black leaders, disrupt the Republican Party, reestablish control over the black labor force, and restore white supremacy in every phase of southern life.” [13]

Allegedly organized for self-defense against state militia units composed of freed blacks they named themselves “White Leagues (Louisiana), White Liners or Rifle Clubs (Mississippi), or Red Shirts (South Carolina). They were, in fact, paramilitary organizations that functioned as armed auxiliaries of the Democratic Party in southern states in their drive to “redeem” the South from “black and tan Negro-Carpetbag rule.” [14] These men, mostly Confederate veterans “rode roughshod over the South, terrorizing newly freed slaves, their carpetbagger allies, and anyone who dared to imagine a biracial democracy as the war’s change.” [15] The unrequited violence and hatred by these men set the stage for the continued persecution, murder and violence against blacks and those who supported their efforts to achieve equality in the South for the next century. In truth the activities of the Klan and other violent White Supremacist groups offer “the most extensive example of homegrown terrorism in American history.” [16]

Throughout his term in office Johnson appealed to arguments used throughout later American history by “critics of civil rights legislation and affirmative action. He appealed to fiscal conservatism, raised the specter of an immense federal bureaucracy trampling on citizens’ rights, and insisted that self-help, not government handouts, was the path to individual advancement.” [17]

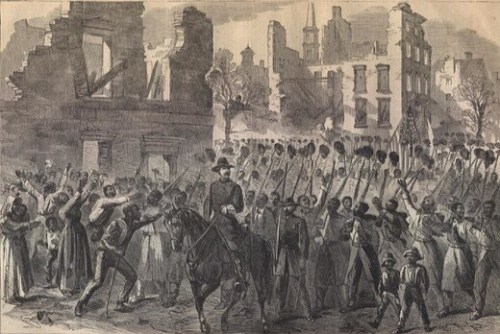

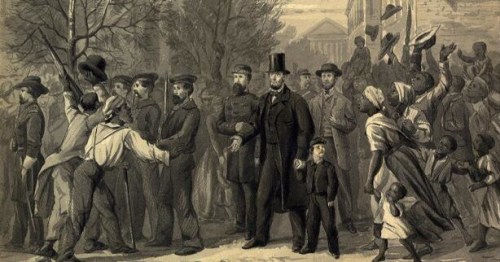

Ulysses S. Grant succeeded Johnson as President in 1869, and unlike his predecessor, he was a man who believed in freedom and equal rights, “For Grant, freedom and equal rights were matters of principle, not symbolism.” [18]Grant ordered his generals in the South to enforce the Reconstruction Act and when the Ku Klux Klan attempted to stop blacks from voting Grant got Congress to pass the “enforcement Act, which made racist terrorism a federal offense.” [19] He created the Justice Department to deal with crimes against Federal law and in 1871 pushed Congress to pass a law known as the Ku Klux Klan Act and sent in the army and federal agents from the Justice Department and the Secret Service to enforce the law.

Grant’s efforts using the military as well as agents of the Justice Department and the Secret Service against the Klan were hugely successful, thousands were arrested, hundreds of Klansmen were convicted and others were either driven underground or disbanded their groups. The 1872 election was the first and last in which blacks were nearly unencumbered as they voted until the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act.

However, Grant’s actions triggered a political backlash that doomed Reconstruction. The seminal moment in this came 1873 when General Philip Sheridan working in Louisiana, asked Grant for “permission to arrest leaders of the White League and try them by courts-martial” [20] for their violent acts against blacks and their seizure of the New Orleans City Hall in a brazen coup attempt. The leak of Sheridan’s request sparked outrage and even northern papers condemned the president’s actions in the harshest of terms.

Apart from the effort to support voting rights for African Americans Grant’s efforts at Reconstruction were met mostly by failure. Part of this was due to weariness on the part of many Northerners to continue to invest any more effort into the effort. Slowly even proponents of Reconstruction began to retreat from it, some like Carl Schurz, were afraid that the use of the military against the Klan in the South could set precedent to use it elsewhere. Others, embraced an understanding of Social Darwinism which stood against all types of government interference what they called the “natural” workings of society, especially misguided efforts to uplift those at the bottom of the social order…and African Americans were consigned by nature to occupy the lowest rungs of the social ladder.” [21]

Southerners knew that they were winning the political battle and continued their pressure in Congress and in the media to demonize supporters of Reconstruction as well as African Americans. Southerners worked to rig the political and judicial process through the use of terror to demoralize and drive from power anyone, black or white, who supported Reconstruction. By 1870 every former Confederate state had been readmitted to the Union, in a sense fulfilling a part Lincoln’s war policy, but at the same time denying what the war was waged for a White led governments aided by the Supreme Court increasingly set about reestablishing the previous social and political order placing blacks in the position of living life under slavery by another name.

The Passage of the Fifteenth Amendment

Slavery had been abolished, and African Americans had become citizens, but in most places they did not have the right to vote. Grant used his political capital to fight for the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave black men the right to vote. It was one of the things that he remained most proud of in his life, he noted that the amendment was, “A measure which makes at once four million people voter who were heretofore declared by the highest tribunal in the land to be not citizens of the United States, nor eligible to become so…is indeed a measure of grander importance than any other act of the kind from the foundation of our free government to the present day.” [22]

To be continued…

Notes

[1] Ibid. Foner A Short History of Reconstruction p.30

[2] Ibid. Lord The Past that Would Not Die pp.11-12

[3] Ibid. Zinn The Other Civil War p.54

[4] Ibid. McPherson The War that Forged a Nation p. 178

[5] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.162

[6] Perman, Michael Illegitimacy and Insurgency in the Reconstructed South in The Civil War and Reconstruction Documents and Essays Third Edition edited by Michael Perman and Amy Murrell Taylor Wadsworth Cengage Learning Boston MA 2011 p.451

[7] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.121

[8] Ibid. Langguth After Lincoln p.232

[9] _____________ The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/amendmentxiv 29 June 2015

[10] Ibid. Carpenter Sword and Olive Branch p.93

[11] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.92

[12] Lane, Charles The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction Henry Holt and Company, New York 2008 p.230

[13] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.171

[14] Ibid. McPherson The War that Forged a Nation p. 178

[15] Ibid. Jordan Marching Home p.118

[16] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.171

[17] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.116

[18] Ibid. Lane The Day Freedom Died: p.2

[19] Ibid. Lane The Day Freedom Died p.4

[20] Ibid. Langguth, A.J. After Lincoln p.314

[21] Ibid. Foner Forever Free pp.192-193

[22] Flood, Charles Bracelen, Grant’s Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant’s Heroic Last Year DaCapo Press, Boston 2011 pp.78-79