Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

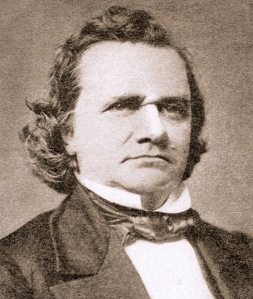

I am taking a break over this Thanksgiving weekend and am re-posting some articles from my Gettysburg text dealing with a man that I consider one of the most fascinating , salacious, scandalous, heroic, and incredible figures ever to grace and disgrace American history, Congressman, and Civil War General Daniel E. Sickles.

I hope that you enjoy,

Peace

Padre Steve+

George Meade had made his dispositions on July 2nd 1863 with care, but there was one notable problem, the commander of III Corps, Major General Dan Sickles did not like the position assigned to his corps on the south end of Cemetery Ridge. But before discussing that it is worth chasing the rabbit so to speak and spend some time on the life of a man referred to by one by one biographer as an American Scoundrel and another as Sickles the Incredible. The interesting thing is that lie most complex characters in history that Dan Sickles was both and, “he might have had more faults than virtues, but everything about him was perfectly genuine.” [1] That is one of the reason that he is so fascinating.

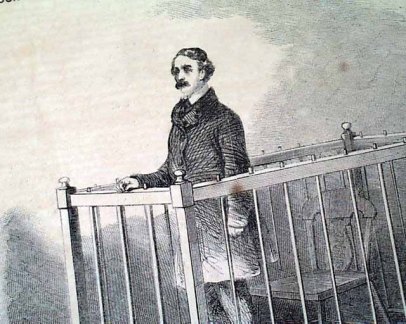

Sickles was certainly a scoundrel and at the same time incredible, charming yet terribly vain and often insincere. “He was quick-witted, willful, brash, and ambitious, with pliable moral principles.” [2] But he was also incredibly brilliant, far sighted, patriotic, and civic minded. He was a political general, “flamboyant, impulsive, and brave, some would wonder about his discipline and military judgement.” [3] His notoriety and unpopularity among the West Point trained professional officers in the Army of the Potomac, as well as his tactical decision to move his corps on the afternoon of July 2nd 1863, and his subsequent political machinations ensured that he would be the only corps commander of that army not commemorated with a monument at Gettysburg.

Dan Sickles was one of the most colorful, controversial, and perhaps the most scandalous officer ever to command a corps in the history of the United States Army. While he lacked professional training he had done a fair amount of study of the military arts in his spare time, and he “made up for his lack of military training by acting on the battlefield with reckless courage, and was much admired for it by his men.” [4]

After having served as a brigade and division commander Sickles was promoted to corps command. “Sickles owed his elevation to corps command to the patronage of his friend Joseph Hooker…. And while man of the West Point officer….regarded Sickles military acumen with the greatest skepticism, many in the volunteer ranks were of a different mind. “Sickles is a great favorite in this corps,” asserted Private John Haley of the 17th Maine. “The men worship him. He is every inch a soldier and looking like a game cock. No one questions his bravery or patriotism.” [5] General Alpheus Williams who commanded a division in the Union Twelfth Corps despised Sickles, and after Chancellorsville Williams wrote “A Sickles’ would beat Napoleon in winning glory not earned,,, He is a hero without a heroic deed! Literally made by scribblers.” [6] Likewise, Sickles, the political general was no favorite of George Gordon Meade.

On July 2nd 1863 Sickles would be responsible for an act that threw George Meade’s defensive plan into chaos, and according to most historians and analysts nearly lost the battle, however, there are some who defend his actions and give him credit for upsetting Lee’s plan of attack. However, the truth lays somewhat in the middle as both observations are correct. Sickles’ decision created a massive controversy in the months following the battle as public hearings in Congress, where Sickles, a former congressman from New York had many friends, as well as enemies, sought a political advantage from a near military disaster.

Sickles was a mercurial, vain and scandal plagued man who “wore notoriety like a cloak” and “whether he was drinking, fighting, wenching or plotting, he was always operating with the throttle wide open.” [7]Sickles was born in New York to George and Susan Marsh Sickles in late 1819, though a number of sources, including Sickles himself cite dates ranging from 1819 through 1825. “There is little reliable information about Sickles’ early days,” [8] and he did not talk much about them, especially after the war, when Gettysburg and the Civil War became his main subjects of conversation. His father, a sixth generation American whose family were early Dutch settlers in Manhattan became wealthy through real estate speculation, “and he passed on to his son a pride in being a congenital Knickerbocker,” charming, witty, and clever, in whom “hardheadedness and impulsiveness were combined.” [9]

The young Sickles was an impetuous child and his father’s wealth ensured that Dan Sickles had “the finest of tutors…. And an unceasing bankroll of funding for lascivious escapades.” [10] To get their son special tutoring to prepare him for college, his parents “arranged for him to live in the scholarly house of the Da Pont family…. It was a household like few others in that hardheaded, mercantile city, at a time when New York had little of the Italian character it would later take on.” [11]The home was a place of learning, culture, and unusual relationships. The head of the house was Lorenzo L. Da Pont, a Professor at Columbia, as well as a practicing attorney. Also living in the home was Da Pont’s father, the ninety-year-old Professor Lorenzo Da Pont, who “had been the librettist for three of Mozart’s operas” [12] and “held the chair of Italian and Columbia University” [13] Additionally, the elder Da Pont’s “adopted daughter Maria and her husband, Antonio Bagioli, a successful composer and music teacher” [14] lived under the same roof.

Maria was only about twenty-years-old when Sickles moved in. By this time she and Bagioli already had a child of their own, a three year old daughter named Teresa, which Sickles would eventually marry. While the elder Da Pont claimed Maria as an adopted daughter, it was “widely believed that she was his “natural child” … from an American liaison conducted when he was near the age of seventy.” [15] This spawned rumors, even at the time of Gettysburg that the young Sickles “and his future mother-in-law had a sexual affair.” [16]

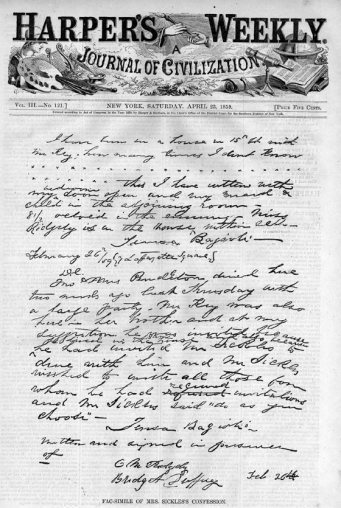

Whether the liaison with Maria Bagioli occurred is a matter of innuendo and conjecture, but it would not be out of character for Sickles, who, to put it mildly, had a wild proclivity for the opposite sex. As a young man he frequented brothels, and as his social and political status increased, he moved from the brothels frequented by the middle class to those which catered to the more socially well to do. One of his affairs was with the a prostitute named Fanny White, a woman who was smart, pretty, and upwardly mobile who ran her own bordello. His affair with Fanny was well publicized, but did not prevent him from being elected to the state legislature in 1847. She and Sickles would continue their relationship for years with her asking nothing more than expensive gifts, and there are inklings that Fanny help to fund Sickles’ early political campaigns. There is also speculation that in 1854 following his marriage, that Fanny spent time with him in London while he was working with James Buchanan and that that he “may have brought Fanny to one of the Queens’s receptions and introducing the prostitute to Her Majesty.” [17] But Fanny eventually moved on to a man older and richer than Sickles. Eventually she retired from her business and married another New York lawyer but died of complications of tuberculosis and possibly syphilis in 1860. Her property at the time of her death was conservatively “estimated at $50,000 to $100,000”[18] a considerable fortune for a woman of her day and age.

While he lived with the Da Pont family, Sickles gained an appreciation for foreign languages, as well as theater and opera. The elder Professor Da Pont was a major part of his academic life and quite possibly in the development of Sickles liberal education and his rather libertine morality. Lorenzo had been a Catholic Priest and theologian in Italy, but like his young American admirer had quite the attraction for women, and was a connoisseur of erotic literature and poetry. His activities resulted in him being expelled from his teaching position in the seminary, after which he became fast friends with a man whose name is synonymous with smooth talking, suave, amorous men, Giacomo Casanova, and in Europe “his affairs with women had been almost as notorious as those of his good friend.” [19] Certainly the elder Lorenzo’s tales “of Casanova, the fabled prince of Priapus, did nothing to quell Dan’s adolescent sexual appetite.” [20]

Noted Civil War and Gettysburg historian Allen Guelzo describes the Sickles in even less flattering terms, “Sickles was from the beginning, a spoiled brat, and he matured from there into a suave, charming, pathological liar, not unlike certain characters in Mozart operas.”[21]

Following the deaths of both the elder and younger Professor Da Pont, Sickles was stricken with grief. At the funeral of the younger Professor Da Pont Sickles “raved and tore up and down the graveyard shrieking,” [22] forcing other mourners to take him away by force. Soon after, Sickles left New York University and began to work in the law office of the very formidable New York lawyer and former U.S. Attorney General, Benjamin F. Butler.

While he was studying for the bar under Butler, he was joined by his father who would also become an attorney. It was under the influence of his father, who was now a wealthy Wall Street investor, and the Democrats of Tammany Hall that the incredibly talented Sickles was groomed for political leadership. Tammany was a rough and tumble world of hardnosed politics, backroom deals, corruption and graft.

He passed the bar in 1843 and soon was making a name for himself in the legal world, and in politics, despite his well-known questionable ethics and morality. His political career began in 1844 when “he wrote a campaign paper for James Polk and became involved in the Tammany Hall political machine.” [23] The ever ambitious Sickles “clambered up the city’s Democratic party ladder, on the way collecting allies and enemies with utter disregard for the consequences, attending the typically unruly Tammany meetings armed with bowie knife and pistol.” [24]

Like many of his fellow New York Democrats he was a proponent of “Manifest Destiny, and the right of the United States to acquire and hold Texas, New Mexico, California, perhaps the isthmus of Central American, and certainly Cuba.” [25] He was also a political ally of many states rights Southern Democrats and “largely opposed anti-slavery legislation.” [26] This was in large part due to the commercial interests of New York, which between banking and commercial shipping interests profited from the South’s slave economy.

He was elected to the New York State legislature in 1847 and his political star continued to rise even as his personal reputation sank among many of his peers. An attorney who knew him described Sickles as “one of the bigger bubbles in the scum of the profession, swollen, and windy, and puffed out with fetid gas.” [27] Sickles rivals any American politician, before or since in his ability to rise even as the slime ran down his body, the term “Teflon” applied to politicians like Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton comes to mind when one studies Sickles’ career. New York lawyer and diarist George Templeton Strong wrote, “One might as well try to spoil a rotten egg as to damage Dan’s career.” [28]

But there was no denying that Sickles was a brilliant lawyer, politician, and debater. One observed that Sickles was “a lawyer by intuition – careful in reaching his conclusions, but quick and bold in pushing them.” [29]New York Governor “William Marcy grudgingly said that as a debater Sickles excelled any man of his years, and the astute Henry Raymond declared that as a parliamentary leader he was unsurpassed.” [30] Soon Sickles was a delegate to the 1848 Democratic Convention where he helped nominate Franklin Pierce for his unsuccessful run at the democratic nomination. The convention enabled Sickles to enter the world of national politics making friends with many influential politicians and financiers, including Pierce, the Van Burens, and James Buchanan. On his return to New York he received an appointed as a Major in the New York Militia.

Even as Sickles rose in the tumultuous world of American law and politics, and chased Fanny White he became enamored with the now teenage daughter of Antonio and Maria Bagioli, Miss Teresa Bagioli who though only fifteen was beautiful, wise beyond her years, fluent in French and Italian, devoted to the arts, and entirely besotted by Dan Sickles. Both the parents of Sickles and Teresa opposed the relationship, but both were madly in love, and Teresa was as headstrong as Dan regarding the relationship. Though such a relationship would be considered completely scandalous today, such marriages were not uncommon then, though they were certainly less common in the upper society of New York. Sickles “was enchanted by her” and “courted her with the sensibility of being a friend of her parents and he must have suspected that he loved her with a fated and exclusive love.” [31] When she was just sixteen Teresa quit school and married the thirty-three year-old assemblyman in a civil ceremony officiated by New York Mayor Ambrose Kingsland on September 27th1852. Six months later, the two were married in the Catholic Church by Archbishop John Hughes, in a “gala and largely attended affair.” [32] Just three months after the church wedding their daughter, Laura, was born. Though there can be no doubt that Sickles loved Teresa, and she him, it did not stop him from other extramarital affairs, nor did it take much away from his political machinations at Tammany Hall.

Following the 1852 Democratic convention where he again supported Franklin Pierce, Sickles hard fighting and influence at in the Wigwam of was rewarded with political plum prize of being appointed “corporation counsel of New York City, a post that paid a flattering salary with extra emoluments and also left room for profitable legal work on the side.” [33] His political and social acumen were again demonstrated as he convinced the state legislature, through personal force of will, to enable the New York City Corporation “to go ahead with creating a great central park,”[34] a park that we now know today as Central Park. He also helped push forward a proposal to create New York’s first mass transportation system, that of horse drawn omnibuses.

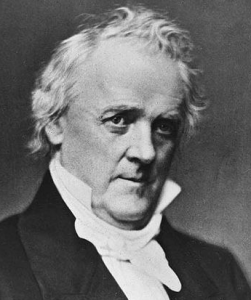

Later in the year Sickles was appointed as secretary of the American legation to the Court of St. James n London, headed by former Secretary of State James Buchanan. The position paid a pittance of what Sickles was earning in New York, but he realized that the serving overseas in such a position could not but help him on the national political stage. Though Buchanan and Pierce wanted Sickles, the new Secretary of State, the former New York Governor William Marcy refused to sign Sickles’ commission for the post. Eventually, Pierce prevailed and Sickles got the job.

As their baby, Laura, was still very young and sea travel still quite hazardous, Teresa remained at home, and joined her husband in London the following year. However, when she arrived in London, the teenage wife of Dan Sickles charmed Americans and Britons alike. Aided by her multilingual gifts, which “were rare among American diplomats’ wives,” [35] she became a great success and the unmarried Buchanan appointed her as hostess for the legation. She rapidly became a celebrity due to her stunning beauty and charm, and like he had Fanny, Sickles had Teresa introduced to the Queen. Her celebrity status evoked different responses from those that observed her. “One contemporary described Teresa as an Italian beauty, warm, openhearted, and unselfish. Another described her as being “… without shame or brain and [having] a lust for men.” [36] That “lust for men” coupled with the neglect of her husband may well have been the catalyst for the scandal which overwhelmed them in Dan’s congressional career.

It was during his service in London with Buchanan that Sickles became embroiled in one of the most embarrassing diplomatic incidents in American history. The proponents of Manifest Destiny and American expansion had long desired to take Cuba from Spain through diplomacy, or if needed force. Following a failed attempt by American “Filibusters” to seize the island in 1852 which ended in the execution of fifty Americans, including the son of U.S. Attorney General John Crittenden by Spanish authorities, and in 1854 President Franklin Pierce authorized Buchanan to attempt to negotiate the acquisition of Cuba.

Pierce authorized Buchanan to meet with James Mason, the United States Ambassador to France and Pierre Soule, the United States Ambassador to Spain secretly in order to draft “a statement on the future of Cuba and the proposed role of the United States.” [37] Soule dominated the meeting and the statement, which was in large part drafted by Dan Sickles, was highly inflammatory. Despite this the statement was released to the press in defiance of the order to maintain the strictest secrecy and it resulted in a diplomatic disaster for the Pierce Administration.

The document was prepared by Soule and Sickles and endorsed by Buchanan and Mason was known as the Ostend Manifesto, and it “was one of the most truly American, and at the same time most undiplomatic, documents every devised.” [38] The manifesto prepared by Soule and Sickles proclaimed that “Cuba is as necessary to the North American Republic as any of its present members, and that it belongs naturally to the great family of states of which the Union is the Providential Nursery.” [39] The authors of the manifesto also threatened Spain should the Spanish fail to accede to American demands. The authors declared that if the United States “decided its sovereignty depended on acquiring Cuba, and if Spain would not pass on sovereignty in the island to the United States by peaceful means, including sale, then, “by every law, human and Divine, we shall be justified in wresting it from Spain.” [40]

The Ostend Manifesto “sent shivers through the chancelleries of Europe, provoked hurried conversations between the heads of the French and British admiralties.” [41] European diplomats and leaders reacted harshly to the statement and Secretary of State William Marcy who had previously supported the ideas in the document immediately distance himself and official American policy from it and the authors. Marcy then “forced Soule’s resignation by repudiating the whole thing, but the damage was done.” For months the Pierce administration was on the defensive, and was condemned “as the advocate of a policy of “shame and dishonor,” the supporter of a “buccaneering document,” a “highwayman’s plea.” American diplomacy, said the London Times, was given to “the habitual pursuit of dishonorable object by clandestine means.”[42] The incident ended official and unofficial attempts by Americans to obtain Cuba by legal or extralegal means until the Spanish American War in 1898.

To be continued…

Notes

[1] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.151

[2] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.222

[3] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command p.45

[4] Sears, Stephen W. Chancellorsville Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 1996 p.65

[5] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.110

[6] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.35

[7] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road pp.150-151

[8] Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettysburg Savas Beatie New York and El Dorado Hills CA, 2009, 2010 p.1

[9] Keneally, Thomas American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles Anchor Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2003 p.7

[10] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg The Last Invasion p.243

[11] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.3

[12] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.2

[13] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.3

[14] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.3

[15] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.4

[16] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.3

[17] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.6

[18] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.215

[19] Swanberg, W.A. Sickles the Incredible copyright by the author 1958 and 1984 Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA 1991 p.79

[20] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.80

[21] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg The Last Invasion p.243

[22] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.81

[23] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.4

[24] Sears, Stephen W. Controversies and Commanders Mariner Books, Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1999 p.198

[25] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.12

[26] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.82

[27] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.222

[28] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.4

[29] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.84

[30] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.84

[31] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.21

[32] Wilson Robert and Clair, Carl They Also Served: Wives of Civil War Generals Xlibris Corporation 2006 p.98

[33] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.88

[34] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.21

[35] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.39

[36] Ibid. Wilson and Clair They Also Served p.98

[37] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.44

[38] Pinchon, Edgcumb Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and “Yankee King of Spain” Doubleday, Doran and Company Inc. Garden City NY 1945 p.48

[39] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.190

[40] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.45

[41] Ibid. Pinchon Dan Sickles p.48

[42] Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis: America before the Civil War 1848-1861 completed and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher Harper Collins Publishers, New York 1976 p.193