Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

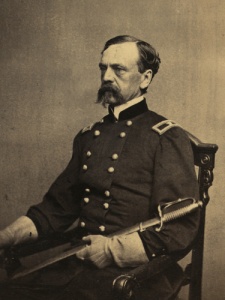

I am taking a break over the next few days to read and reflect. So I am re-posting some articles from my Gettysburg text dealing with a man that I consider one of the most fascinating , salacious, scandalous, heroic, and incredible figures ever to grace and disgrace American history, Congressman, and Civil War General Daniel E. Sickles.

I hope that you enjoy,

Peace

Padre Steve+

Dan Sickles completed his term in Congress making few speeches and maintaining a relatively low profile, frequently entering and leaving through side entrances. But as tensions rose and secession fever built, Sickles, the longstanding supporter of Southern states rights, who had declined to run for reelection “briefly transformed himself from outcast to firebrand” [1]when secessionist troops opened fire on the transport Star of the West when that ship attempted to deliver supplies to Fort Sumter. Surprising his Southern colleagues he declared the attack on the ship as “naked, unmitigated war,” and declared:

It will never do, sir, for them [the South] to protest against coercion and, at the same moment, seize all the arms and arsenals and forts and navy-yards and ships… when sovereign states by their own deliberate acts, make war, they must not cry peace… When the flag of the Union is insulted, when the fortified place provided for the common defense are assaulted and seized, when the South abandons its Northern friends for English and French alliances, then the loyal and patriotic population of that imperial city [New York] are unanimous for the Union.” [2]

He declared the assault to an act of war, and predicted that “the men of New York would go in untold thousands anywhere to protect the flag of its country and to maintain its legitimate authority.” [3] Sickles’ speech was electrifying and heartened back to his early career and what might have been, and during the remaining days of his term he continued to speak out in the House against the actions of the South and sponsored legislation to bills to suspend postal service with the South and recover the funds in the United States Mint buildings which had been seized by seceding states. He thundered in the presence of Southern friends still serving in the House, “Surely the chivalrous men of the South would scorn to receive the benefit of our postal laws,… “They cannot intend to remain, like Mahomid’s coffin, between heaven and earth, neither in nor out of the Union, getting all the benefits, and subjecting us to all its burdens.” [4]

Shortly thereafter Dan Sickles left Washington to what many thought would be political and possibly personal oblivion, but they underestimated Sickles. Ambition and the desire for redemption still burned in his heart, and shortly after President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion, Sickles volunteered to help raise and lead the men of the Empire State into battle to restore the Union. As the future commander of a one of the regiments, the French born journalist, Regis De Trobriand, noted “during the lead-up to Sumter, Dan had been among the conciliatory and moderate, “but when the sword was drawn, he was one of the first to throw away the scabbard.” [5]

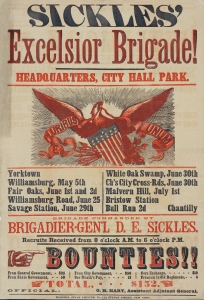

Taking up the challenge to raise a regiment sickles went to work, and “almost overnight, using flag-waving oratory, organizational skills, and promissory notes, he had his regiment, the 70th New York volunteers well in hand.” [6] Soon his authority was expanded to recruit a brigade, which rapidly filled with volunteers, soon over 3,000 men were under his command, and the new brigade, consisting of the 70th, 71st, 72nd, 73rd and 74thNew York Volunteers which Sickles promptly christened the Excelsior Brigade, taking on the Empire State’s motto. However many of the brigade’s volunteers were scorned because of Sickles’ reputation, the brigade’s historian wrote, “no name was too bad for you; one would call you this and another would call you that, and even a person’s own relatives would censure him for joining such a Brigade as that of Daniel E. Sickles.”[7]

Even so, Sickles rapidly captured the hearts of his men. Volunteers were found throughout New York, as well as New Jersey, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, and the men represented the spectrum of White America; men of traditional Anglo-Saxon origin mingled with Irish, Germans, and Dutch. But he was so successful in recruiting that organizers of other regiments, especially in rural New York counties demanded that the Republican governor, Edward Morgan, order Sickles to disband most of the brigade. Believing the action politically motivated, Sickles refused and went directly to Lincoln to get the brigade Federal recognition. At first Lincoln balked at the request, he needed troops but was yet unwilling to get in the way of what he saw as the individual state control of their militias. The result was an impasse as Federal and New York officials argued about the brigade and the status of Sickles himself.

Sickles organizational and leadership skills were tested by the situation, and he went to extraordinary lengths to meet the needs of his soldiers for housing, food and sanitation, “and financed its camp for some time out of his own purse…. At one point he rented a circus tent from P.T. Barnum to house several hundred of his recruits. At another, with several companies or more quartered in a bare hall on lower Broadway, he contracted a cheap bath-house to give fourteen hundred men a shave and shower at ten cents apiece.” [8] To meet the need for cooked meals Sickles’ old friend Captain Wiley “commandeered cooks for the brigade from Delmonico’s, working in inadequate kitchens in side streets, they tried to turn out enough food for the men.” [9] Eventually the brigade was given a campsite on “Staten Island, near Fort Wadsworth, where he and his men could wait until the issue of mustering-in was settled.” [10]

Finally in July of 1861 the Excelsiors were officially mustered in to service as New York Volunteer troops and Sickles commissioned as a Colonel, functioning as the commander of the 70th New York and the de-facto commander of the brigade. Lincoln nominated Sickles for a commission as a Brigadier General of Volunteers but due to pressure from New York officials, still steaming at Sickles for going to Lincoln, and the Senate delated confirmation for months, forcing Lincoln to re-nominate him a second time after which they confirmed him in May 1862, in some measure due to the influence of Sickles former defense attorney, Edwin Stanton who had succeeded Simon Cameron as Secretary of War.

Sickles and his brigade first saw combat at Fair Oaks during the Seven Day’s battle. Sickles acquitted himself well during the fighting, he seemed to be a natural leader of men, who cheered him as he led them into battle. The actions of the Excelsiors and their newly minted Brigadier were praised by the Army commander, George McClellan in a letter to Stanton, “The dashing charge of the Second and Fourth Regiments,…”the cool and steady advance of the Third, occurred under my immediate observation and could not have been surpassed.” [11] A news correspondent attached to the army wrote:

“Gen. Sickles had several narrow escapes; he was always to be found in the thickest of the fight. Had those gifted Senators who refused to confirm his nomination, but witnessed the enthusiasm of his troops when serving under him, and his military qualifications for office, they would do penance until re-elected.” [12]

The success at Fair Oaks was not followed up by McClellan, despite the urging of many officers, including Sickles and Richmond, which many believed could have been taken, remained in Confederate hands. Sickles performance during the Peninsular Campaign won Dan the respect and affection of his soldiers, as well as the respect of his division commander Fighting Joe Hooker. Unlike many other leaders who in their first taste of combat on the Peninsula saw the terrible carnage of battle, the immense numbers of casualties, and the suffering of the troops, Sickles maintained his composure, as others collapsed, “neither the casualties nor the state of the earth daunted Sickles.” [13] Hundreds of his Excelsiors, including his own aid-de-camp were killed or wounded during the campaign, and “the Excelsior Brigade, through steadily reduced by deaths, wounds and illness, had been forged into a body of hard-bitten, battle-wise soldiers educated in the necessities of war and in the tricks of self-preservation.” [14] A member of the brigade wrote, “It is no fable about the men of this Brigade thinking a great deal of the General.” [15]

Following the army’s withdraw from the Peninsula and its return to encampments near Washington D.C. Sickles went back to New York to raise new troops to replace those killed or wounded during the campaign. He also took time to organize efforts to care of the children of the brigade’s soldiers, living and dead who were being taken care of at the Union Home School. Due to this he missed the battles of Second Bull Run and Antietam. His recruiting efforts were successful, even former political enemies were impressed by his service, and his ability to raise and organize troops. His reputation had been so completely rehabilitated by his war service that some of his “old backers in Tammany wanted him to run again for Congress,” [16] but he was opposed by others, like his old friend Sam Butterworth, who had become a “Copperhead,” an anti-war, faction that wanted to end the war and let the South go on its way; “to them, Dan had become a Lincoln man, a crypto-Republican.” [17] the relief of many of his troops he declined the offer to run again. As one of his Chaplains, Joseph Twitchell noted Sickles, “is getting fixed in his new place most successfully and will probably serve himself, as well as the country, better here than in a war of words.” [18]

During his recruiting efforts Sickles, now a military, as well as political realist, made many speeches, in which he recognized that conscription was inevitable. Having seen the brutal cost of war and the suffering of his men, Sickles complained of the lack of effort being provided in New York to the war effort. In a speech at the Produce Exchange, he praised the leadership and nerve of President Lincoln, and said, “A man may pass through New York, and unless he is told of it, he would not know that this country is a war…. In God’s name, let the state of New York have it to say hereafter that she furnished her quota for the army without conscription – without resorting to a draft!” [19]

When he returned to the army in November of 1862 his old division commander, Hooker had been promoted to corps command following the relief of George McClellan, and as the senior brigadier was promoted to command of the division. His, division, the Second Division of Third Corps was used in a support role at Fredericksburg and saw little action in that fight and only suffered about 100 casualties. His old friend and defense counsel Thomas Meagher, now commanding the Irish Brigade saw his brigade shattered in the carnage of at Fredericksburg. After Ambrose Burnside who had commanded the army during that fiasco was relieved of command Hooker was appointed by Lincoln as commander of the Army of the Potomac.

One of Hooker’s organizational changes was to establish a Cavalry Corps which was to be commanded by Major General George Stoneman, the commander of Third Corps. This left “Sickles as the corps’ ranking officer.” [20] Sickles was promoted to command the Third Corps by Hooker, who chose Sickles over another volunteer officer, David Birney. Had a professional officer rather than Birney been his competition, “Sickles would have remained division commander.” [21] Sickles was given the corps “on a provisional basis, for his appointment as a major general had not yet been confirmed by the Senate and corps command was definitely a two-star job.”[22]Once again it was political enemies in the Senate, this time Republicans who did not trust the Democrat, who delayed Sickles’ promotion to Major General, but he was finally confirmed on March 9th 1863, with his promotion backdated to November 29th of 1862. “Professionals in the army attributed his rise to his “skill as a political maneuverer.” Few men, however, questioned his personal bravery.” [23]

To be continued…

Notes

[1] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.21

[2] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.111

[3] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p. 212

[4] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.214

[5] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.219

[6] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.201

[7] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.23

[8] Ibid. Catton Glory Road p. 153

[9] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.222

[10] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.222

[11] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg pp.30-31

[12] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.149

[13] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.245

[14] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.153

[15] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.222

[16] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.32

[17] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.245

[18] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.32

[19] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.252

[20] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.223

[21] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.206

[22] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.168

[23] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.223