Major General Robert Rodes

Major General Robert Rodes was new to commanding a division. The big, blond and charismatic Rodes was one of the most popular leaders in the Army of Northern Virginia. Rodes had a great ability to inspire his subordinates, in part due to his physical appearance which was “as if he had stepped from the pages of Beowulf” [1] but also due to his “bluff personality featuring “blunt speech” and a tincture of “blarney.” [2]

Rodes graduated at the age of 19 from the Virginia Military Institute and remained at the school as an assistant professor for three years. He left VMI when Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson received the full professorship he desired and became a successful civil engineer working with railroads in Alabama. He had just been appointed a full professor at VMI as the war was declared. [3]

With the coming of war Rodes abandoned his academic endeavors and was appointed Colonel of the 5th Alabama regiment of infantry. Early in the war Rodes distinguished himself as the commander of that regiment and later as a brigade commander. He took acting command of Major General D. H. Hill’s former division at Chancellorsville and handled that unit well. Following Chancellorsville Rodes was recommend for promotion to Major General and permanent command the division by Stonewall Jackson, in one of his last acts before his untimely death from pneumonia as that remarkable commander recovered from wounds sustained at Chancellorsville. With his appointment Rodes was the first non-West Point graduate to command a division in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Rodes’ division was the largest in the Army of Northern Virginia. Composed of five brigades and numbering around 8000 men it was a powerful force. All of its brigades save one had seen action before, but that large brigade of 2200 men was well trained and commanded by West Point graduate Junius Daniel [4] and was expected to perform well despite its inexperience.

The despite Gettysburg campaign was to be Rodes first command as a Major General and his brigade commanders were an uneven lot. Following the heavy losses in senior officers at Chancellorsville experienced and competent officers were becoming harder to come by. As a result some brigades were commanded by officers either not experienced or competent in their new commands.

Rodes was fortunate to have Brigadier Generals Stephen Ramsuer and George Doles in command of two of his brigades. Both had led their units well at Chancellorsville under Rodes direction, and would fight well in Gettysburg and subsequent actions. [5] Brigadier General Junius Daniel, though experienced was new to the Army of Northern Virginia and his brigade untested.

Brigadier General Alfred Iverson

This left two brigades under questionable leadership. One brigade from North Carolina was commanded by Brigadier General Alfred Iverson. Iverson who was considered a “reliable secession enthusiast” was appointed to command the North Carolina troops whose political steadiness and loyalty was questioned by Richmond. [6] Because of this Iverson became “embroiled in bitter turmoil with his North Carolinians.” [7] Iverson both in the Mexican War, the 1850s and in his service to the Confederacy owed his position to political appointments and patronage. Though he was from Georgia he helped raise the 20th North Carolina regiment of infantry and became its first Colonel. However he was constantly at war with his officers and his regiment never bonded with him. As a regimental commander he did see a fair amount of action but his leadership was always a question mark. After he took command of the brigade Iverson “sent an aide to the camp of his former regiment to arrest all twenty-six of its officers.” [8] Those officers responded in kind and “retained a powerful bevy of counsel including…Colonel William Bynum who would later become a member of the Supreme Court.” [9] Iverson then refused promotions to any officer who had opposed him. One of the aggrieved officers of the 20th North Carolina “wrote an outraged letter home insisting that resistance to Iverson was every reasonable man’s duty and asserting that he would oppose him again “with great pleasure” if the occasion offered.” [10] In his previous action at Chancellorsville Iverson “had not distinguished himself.” [11] After Chancellorsville he had “been stigmatized for his conspicuous absence at the height of the fighting.” [12]

Colonel Edward A. O’Neal

The last brigade to mention is the brigade which Rodes had commanded prior to taking command of the division at Chancellorsville. Due to the lack of qualified officers it was commanded by its senior regimental commander Colonel Edward A. O’Neal. O’Neal was another political animal, who unlike Iverson had no prior military training and nothing he had done before the war “had prepared him for command at any level.” [13] As an Alabama lawyer O’Neal was however well connected politically which gained him rapid rank and seniority over other officers, this eventually led to his command of the 26th Alabama which was a part of Rodes brigade. Rodes had reservations about O’Neal’s ability to command the brigade and recommended two other officers, John Gordon and John T. Morgan who instead were assigned to other brigades and both of whom became General Officers, [14] Gordon finish the war as a Lieutenant General and commander of Second Corps. Richmond forwarded a commission to Lee for O’Neal to be promoted to Brigadier General but Lee, obviously with reservations about O’Neal’s capabilities blocked the promotion. [15]

On June 30th Rodes’ division marched about twenty miles and bivouacked at Heidlersburg where he met with his corps commander Ewell, fellow division commander Jubal Early and Isaac Trimble who was accompanying Second Corps where they puzzled over Lee’s orders as to the movement of Second Corps the following day, which indicated that Ewell should march to Gettysburg or Cashtown “as circumstances may dictate.” [16] Neither Rodes nor Early gave favorable opinions of the order and Ewell asked the rhetorical question “Why can’t a commanding General have someone on his staff who can write an intelligible order?” [17]

Ewell who assumed that Cashtown was the desired junction of the army ordered his to march from on the morning of July 1st 1863 toward Cashtown to join with Hill’s corps. His choice of routes was good as it gave him the opportunity to turn south towards Gettysburg “as circumstances” dictated.[18] Rodes division was at Middletown (modern Bilgerville) when Ewell was informed that Hill’s troops were in action against Federal cavalry outside of Gettysburg. Ewell then ordered his divisions south to support Hill’s corps in its attack even though he was not clear on what the strength or composition of the Federal forces. [19]

Like Heth to his west Rodes was also operating somewhat independently and like Heth when confronted with the opportunity for battle ignored the instruction “to avoid a general engagement, if practicable.” [20] The operation was Rodes’ first as a Major General and he like the other commanders in Second Corps was operating independently “as Ewell preferred.” [21] About four miles north of the town Rodes wrote that “to my surprise, the presence of the enemy there in force was announced by the sound of a sharp cannonade, and instant preparations for battle were made.” [22]

The arrival of Rodes’ division as well as Early’s division was decisive in turning the tide of the battle toward the Confederates that afternoon. The Union I Corps and Buford’s cavalry division had fought Heth’s poorly coordinated and led attacks to a standstill, but when Rodes arrived he found “a golden opportunity spread before him.” [23] From his position at Oak Ridge he saw the opportunity to take the Federal troops opposing Hill in the flank though his position did not “provide him as comprehensive view as he thought. [24] He also saw the divisions of Howard’s XI Corps advancing out of Gettysburg and moving north.

Rodes brought up Carter’s artillery battalion and ordered it to fire on the Union positions. This and the reports from Devin’s brigade of Buford’s cavalry division deployed north of the town alerted the commanders of I Corps who turned to meet the new threat from their north.

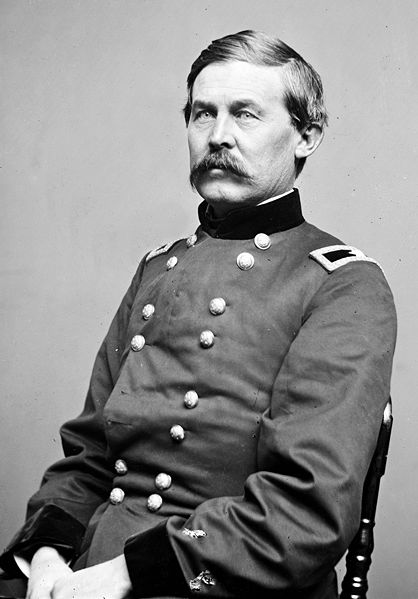

Captain Hubert Dilger

Carter’s artillery, deployed in the open immediately drew the fire of Captain Hubert Dilger’s Battery I First Ohio Artillery from Howard’s XI Corps. Dilger commanded one of the best artillery units in the army, a German immigrant and artilleryman serving in the Grand Duke of Baden’s Horse Artillery at the beginning of the war arrived in the United States at the invitation of a distant uncle, to “practice the war-making he had only previously rehearsed.” [25] Dilger was “blunt and a bit arrogant…loved by his men but not by his superiors.” At Chancellorsville he and his battery had helped save the Federal right “when it used a leapfrogging technique to keep the victorious Confederate infantry at bay.” [26] The effect of Dilger’s fire was blasted carter’s artillery blowing up several caissons and guns causing casualties among the men. [27]

Dilger’s Battery goes into action

Dilger’s Battery goes into action

Thinking he had an adequate grasp of the situation Rodes did not order a reconnaissance before launching his attack, nor did the brigades assigned to it put out skirmishers, a normal precaution when advancing to the attack. [28] Rodes deployed his troops over the rough ground of the ridge as quickly as he could and dashed off a note to Jubal Early stating “I con burst through the enemy in an hour.” [29] He was to be badly mistaken.

Rodes deployed Doles’ excellent brigade to guard his left against the advancing XI Corps units a task which it conducted admirably until the arrival of Jubal Early’s division and after which it too joined the attack on XI Corps. Initially this opened a gap between Doles and the rest of the division but this could not be exploited by the Federals.

His division initially deployed on a one brigade front. As they neared the Federal positions Rodes developed a relatively simple plan to “attack on a two brigade front, sending in O’Neal’s and Iverson’s men simultaneously, then following up with Daniel’s brigade in echelon on the right.” [30] It was a sound plan, but in execution it was “bungled right at the start.” [31] Direction was faulty, units were mingled and a gap developed between O’Neal and Iverson. [32]

O’Neal’s brigade had stalled almost immediately when fired upon by Union troops who had been hidden by a wall which had obscured them from Rodes’ view. Striking the O’Neal’s advancing troops at the oblique the Union troops wreaked havoc on the unsuspecting Confederates. These men were solid veterans from Baxter’s brigade of Robinson’s division as well as Dilger’s artillery which delivered effective canister fire at O’Neal’s brigade” [33] which “killed or wounded about half of the advancing men with a series of point blank volleys pumped directly into their flank.” [34] To further complicate matters O’Neal had chosen to remain back with his reserve regiment rather than “going forward to direct the advancing regiments.” [35] Rodes noted in his after action report that O’Neal’s three attacking regiments “moved with alacrity (but not in accordance with my orders as to direction)” and when he ordered the 5th Alabama up to support “I found Colonel O’Neal, instead of personally superintending the movements of his brigade, had chosen to remain with his reserve regiment. The result was that the whole brigade was repulsed quickly and with loss….” [36]

As Rodes bad luck would have it Iverson on O’Neal’s right did not advance simultaneously or on the same axis, but in waited to see O’Neal’s advance. Like O’Neal, Iverson did not advance with or direct his advancing troops. [37] As a result the brigade drifted right and its exposed left was subject to attack from Baxter’s, Paul’s and Hook’s brigades of Robinson’s division. Like O’Neal’s brigade it too blundered into the path of well concealed veterans who like they did with O’Neal’s Alabamians and slaughtered them. The Federals advanced into the broken ranks of the North Carolina regiments they captured many. Official Confederate reports list only 308 missing but that number differs from the Union reports, Robinson reporting 1000 prisoners and three flags and Baxter’s nearly 400 alone. [38]

The 88th Pennsylvania Charges Iverson’s Brigade

The 88th Pennsylvania Charges Iverson’s Brigade

Iverson was badly shaken by the slaughter and “went to pieces and became unfit for further command,” [39] being just close enough to observe it. He panicked and notified Rodes that one of his regiments had surrendered in masse though he later retracted that in his official report where he noted “when I found afterward that 500 of my men were left lying dead and wounded on a line as straight as a dress parade, I exonerated …the survivors.” [40] His brigade had lost over two-thirds of its strength in those few minutes, one regiment the 23rd North Carolina lost 89 percent of those it took into battle, and at the end of the day would “count but 34 men in its ranks.” [41] Iverson’s conduct during the battle was highly criticized by fellow officers after it. Accused of cowardice, drunkenness and hiding during the action he was relieved of his command upon the army’s return to Virginia “for misconduct at Gettysburg” [42] and sent back to Georgia. Some complained after the war that Iverson was helped by politicians once he returned to Richmond and instead of facing trial “got off scot free & and had brigade of reserves given to him in Georgia.” [43]

With the center of his attacking forces crushed the brigades of Junius Daniels and Stephen Ramseur entered the fray to the right of Iverson’s smashed brigade. These capable officers achieved a link up with the battered brigades of Harry Heth at the Railroad cut after Daniel’s brigade had fought a fierce battle with Culter’s and Stone’s brigades in the area [44] and allowed the Confederates a unified front with which they pressed east. To the east Doles’ brigade advanced with Jubal Early’s division smashed the outnumbered and badly spread out divisions of Oliver Howard’s XI Corps. The timely arrival of that division coupled with the skillful work of Daniel and Ramseur saved Rodes from even more misfortune on that first day of battle, but Rodes’ plan “to burst through the enemy” with his division had evaporated. [45] Rodes’ division lost 3000 of its 8000 men present killed, wounded or captured in those few short hours on July 1st 1863.

The battle at Oak Ridge was a series of tactical debacles within a day of what appeared to be a “Confederate strategic bonanza.” [46] Despite the mistakes Rodes never lost his own self-control. He recovered from each mistake and continued to lead his division. He “kept his men on the ridge driving forward until with Hill, and on the flats left joined Early’s right to form a continuous line into Gettysburg.” [47] It was a hard lesson for the young Major General, but one that he learned from. He would be killed at killed at the Third Battle of Winchester on September 19th 1864.

Notes:

[1] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.39

[2] Krick, Robert K. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day of Gettysburg in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.115

[3] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.123

[4] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.53

[5] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.117

[6] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.25

[7] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.53

[8] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.129

[9] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.131

[10] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.130-131

[11] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.564

[12] Tredeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.145

[13] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.120

[14] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.123

[15] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p.162Also see Krick pp.123-124 Following Gettysburg Lee continued to block O’Neal’s promotion and that officer went to extraordinary lengths to obtain a General’s commission using every political ally he had in Alabama and in Richmond. Finally Lee settled the matter before the Wilderness campaign writing that he made “more particular inquiries into his capacity to command the brigade and I cannot recommend him to the command.” Krick pp.123-124

[16] Ibid Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.148

[17] Ibid Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.149

[18] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.160

[19] Ibid Tredeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.169-170

[20] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.564

[21] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.472

[22] Luvaas, Jay and Nelson Harold W editors. The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg South Mountain Press, Carlisle PA 1986 p.35

[23] Ibid. Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.472

[24] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[25] Ibid Tredeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.208

[26] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 pp.59-60 Dilger was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Chancellorsville in 1893, part of the citation stating that Dilger: “fought his guns until the enemy were upon him, then with one gun hauled in the road by hand he formed the rear guard and kept the enemy at bay by the rapidity of his fire and was the last man in the retreat.”

[27] Ibid Tredeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.210

[28] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[29] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[30] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.197

[31] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.197

[32] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.565

[33] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.198

[34] Ibid. Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.473

[35] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.565

[36] Ibid Luvaas The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg p.36

[37] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.132

[38] Ibid Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.175

[39] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.290

[40] Ibid Luvaas The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg p.37

[41] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.201

[42] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.173

[43] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.136

[44] Ibid. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.292

[45] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.173

[46] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.138

[47] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.138