Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

Today I am posting yet another major revision to the opening chapter to my Civil War and Gettysburg text. It is the follow up section to yesterday’s article on the Emancipation Proclamation and deals with the service of African American men in the U.S. Army. This was a major step in the long road to equality for African Americans, a task that is not fully complete, but has also benefited many other Americans of different races as well as women and LGBTQ people. I hope that you enjoy the read, but more importantly appreciate what those men went through to blaze a trail for freedom.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

From Slavery to Soldiering

But as the war continued on, consuming vast numbers of lives the attitude of Lincoln and his administration began to change. After a year and a half of war, Lincoln and the closest members of his cabinet were beginning to understand that the “North could not win the war without mobilizing all of its resources and striking against Southern resources used to sustain the Confederate war effort.” [1] Slave labor was essential to the Confederate war effort, not only did slaves still work the plantations, they were impressed into service in war industries as well as in the Confederate Army.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Freemantle, a British observer who was with Lee’s army at Gettysburg noted, “in the rear of each regiment were from twenty to thirty negro slaves.” [2] The fact is that the slaves who accompanied the army remained slaves, they were not the mythical thousands of black soldiers who rallied to the Confederate cause, nor were they employees. “Tens of thousands of slaves accompanied their owners to army camps as servants or were impressed into service to construct fortifications and do other work for the Confederate army.” [3] This fact attested to by Colonel William Allan, one of Stonewall Jackson’s staff members who wrote “there were no employees in the Confederate army.” [4] slaves served in a number of capacities to free up white soldiers for combat duties, “from driving wagons to unloading trains and other conveyances. In hospitals they could perform work as nurses and laborers to ease the burdens of patients.” [5] An English-born artilleryman in Lee’s army wrote in 1863 that “in our whole army there must be at least thirty thousand colored servants….” [6] When Lee marched to Gettysburg he did so with somewhere between ten and thirty-thousand slaves in support roles and during the advance into Virginia Confederate troops rounded up and re-enslaved as many blacks as they could, including Freedmen.

Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton; who was a passionate believer in the justice of emancipation, was one of the first to grasp the importance of slave labor to the Confederate armies and how emancipation was of decided military necessity. Stanton, “Instantly grasped the military value of the proclamation. Having spent more time than any of his colleagues contemplating the logistical problems facing the army, he understood the tremendous advantage to be gained if the massive workforce of slaves could be transferred from the Confederacy to the Union.” [7]

Lincoln emphasized the “military necessity” of emancipation and “justified the step as a “fit and necessary war measure for suppressing the rebellion.” [8] The process of emancipation now became not only a moral crusade, but now became a key part of national strategy, not just in a military means, but politically, economically and diplomatically as Lincoln “also calculated that making slavery a target of the war would counteract the rising clamor in Britain for recognition of the Confederacy.” [9]

Lincoln wrote to his future Vice President, Andrew Johnson, then the military governor of occupied Tennessee that “The colored population is the great available and yet unavailed of, force for restoration of the Union.” [10] The idea of simply mollifying the border states was dropped and policy changed that of “depriving the Confederacy of slave labor. Mobilizing that manpower for the Union – as soldiers as well as laborers – was a natural corollary.” [11] Reflecting President Lincoln’s and Stanton’s argument for the military necessity of emancipation, General Henry Halleck wrote to Ulysses Grant that:

“the character of the war has very much changed within the past year. There is now no possibility of reconciliation with the rebels… We must conquer the rebels or be conquered by them….Every slave withdrawn from the enemy is the equivalent of a white man put hors de combat.” [12]

Grant concurred with the decision. Grant wrote to in a letter to Lincoln after the assault on Battery Wagner by the 54th Massachusetts, “by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion as it strengthens us.” [13] William Tecumseh Sherman was supportive but also noted some facts that some radical abolitionists did not understand. He noted in his correspondence that, “The first step in the liberation of the Negro from bondage will be to get him and his family to a place of safety… then to afford him the means of providing for his family,… then gradually use a proportion – greater and greater each year – as sailors and soldiers.” [14] Lincoln wrote after the Emancipation Proclamation that “the emancipation policy, and the use of colored troops, constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the rebellion.” [15] The change was a watershed in both American history as well as the future of the U.S. Military services.

In conjunction with the Emancipation Proclamation Secretary of War Stanton “authorized General Rufus Saxton to “arm, uniform, equip, and receive into the service of the United States such number of volunteers of African descent as you may deem expedient, not exceeding 5,000, and [you] may detail officers to instruct them in military drill, discipline, and duty, and to command them.” [16] The initial regiments of African Americans were formed by Union commanders in liberated areas of Louisiana and South Carolina, and most were composed of newly freed slaves. Others like the 54th Massachusetts were raised from free black men in the north. Stanton’s authorization was followed by the Enrollment Act passed by Congress in March of 1863 which established the draft also allowed blacks to serve. By March Stanton was working with state governors to establish more black regiments. The units became known as United States Colored Troops, or U.S.C.T. and were commanded by white officers and organized into the infantry, cavalry and, artillery regiments organized on the model of white regiments. The U.S.C.T. “grew to include seven regiments of cavalry, more than a dozen of artillery, and well over one hundred of infantry.” [17]

Some Union soldiers and officers initially opposed enlisting blacks at all, and some “charged that making soldiers of blacks would be a threat to white supremacy, and hundreds of Billy Yanks wrote home that they would no serve alongside blacks.” [18] But most common soldiers accepted emancipation, especially those who had served in the South and seen the misery that many salves endured, one Illinois soldier, stationed who served in the Western Theater of war wrote, “the necessity of emancipation is forced upon us by the inevitable events of the war… and the only road out of this war is by blows aimed at the heart of the Rebellion…. If slavery should be left undisturbed the war would be protracted until the loss of life and national bankruptcy would make peace desirable on any terms.” [19] Even so racial prejudice in the Union ranks never went away and sometimes was accompanied by violence. It remained a part and parcel of life in and outside of the army, even though many Union soldiers would come to praise the soldierly accomplishments and bravery of African American Soldiers. An officer who had refused a commission to serve with a U.S.C.T. regiment watched as black troops attacked the defenses of Richmond in September 1864:

“The darkies rushed across the open space fronting the work, under a fire which caused them loss, into the abattis… down into the ditch with ladders, up and over the parapet with flying flags, and down among, and on top of, the astonished enemy, who left in utmost haste…. Then and there I decided that ‘the black man could fight’ for his freedom, and that I had made a mistake in not commanding them.” [20]

“Once the Lincoln administration broke the color barrier of the army, blacks stepped forward in large numbers. Service in the army offered to blacks the opportunity to strike a decisive blow for freedom….” [21] Emancipation allowed for the formation of regiments of United States Colored Troops (USCT), mustered directly into Federal service, which in numbers soon dwarfed the few state raised Black Regiments. However, it was the inspiration provided by those first state raised regiments, the heroic accounts of those units reported in Northern newspapers, as well as the unprovoked violence directed against Blacks in the 1863 draft riots that helped to provoke “many northerners into a backlash against the consequences of violent racism.” [22]

Despite the hurdles and prejudices that blacks faced even in the North, many African Americans urged others to enlist, self-help mattered more than self-preservation. Henry Gooding, an black sergeant from Massachusetts wrote the editor of the New Bedford Mercury urging fellow blacks to enlist despite the dangers, “As one of the race, I beseech you not to trust a fancied security, laying in your minds, that our condition will be bettered because slavery must die…[If we] allow that slavery will die without the aid of our race to kill it – language cannot depict the indignity, the scorn, and perhaps the violence that will be heaped upon us.” [23]

The valor of the state regiments, as well as the USCT units that managed to get into action was remarkable, especially in regard to the amount of discrimination levied at them by some northerners, and the very real threat of death that they faced if captured by Confederates. In response to the Emancipation Proclamation and to the formation of African American regiments the Confederate Congress passed

In May of 1863 Major General Nathaniel Banks dared to send the First and Third Regiments of “Louisiana Native Home Guard regiments on a series of attacks on Confederate positions at Port Hudson, Louisiana” [24] where they received their baptism of fire. They suffered heavy losses and “of the 1080 men in the ranks, 271 were hit, or one out of every four.” [25] Banks said of them in his after action report: “They answered every expectation…In many respects their conduct was heroic…The severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leave upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success.” [26]

Men of the 4th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops

But the most famous African American volunteer regiment was the 54th Massachusetts, commanded by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the “North’s showcase black regiment.” [27] Raised in Boston and officered by many men who were the sons of Boston’s blue blood abolitionist elite, the regiment was authorized in March 1863. Since there was still opposition to the formation of units made up of African Americans, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew authorized the formation of the 54th under the command of white officers, a practice that with few exceptions, became standard in the U.S. military until President Truman desegregated the armed forces in 1948. Governor Andrew was determined to ensure that the officers of the 54th were men of “firm antislavery principles…superior to a vulgar contempt for color.” [28]

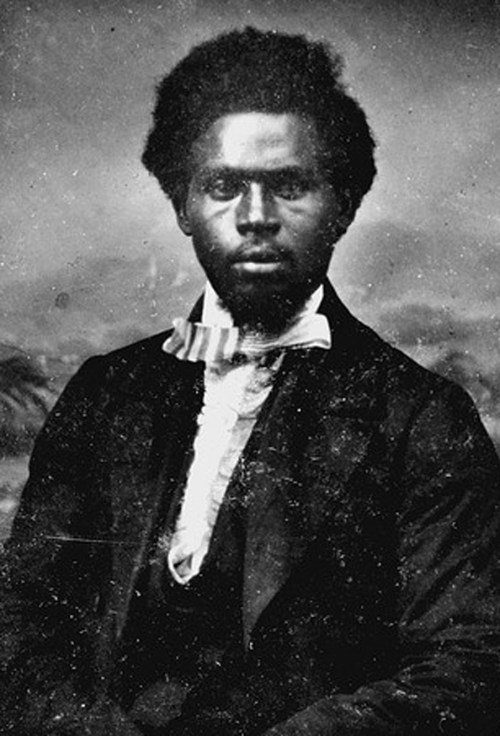

Lieutenant Stephen Swails

The 54th Massachusetts first saw action in early June 1863 and at Shaw’s urging were sent into battle against the Confederate positions at Fort Wagner on July 18th 1863. Leading the attack the 54th lost nearly half its men, “including Colonel Shaw with a bullet through his heart. Black soldiers gained Wagner’s parapet and held it for an hour before falling back.” [29] Though they tried to hold on they were pushed back after a stubborn fight to secure a breach in the fort’s defenses. “Sergeant William H Carney staggered back from the fort with wounds in his chest and right arm, but with the regiment’s Stars and Stripes securely in his grasp. “The old flag never touched the ground, boys,” Carney gasped as he collapsed at the first field hospital he could find.” [30] Shaw was buried with his men by the Confederates and when Union commanders asked for the return of his body were told “We have buried him with his niggers,” Shaw’s father quelled a northern effort to recover his son’s body with these words: We hold that a soldier’s most appropriate burial-place is on the field where he has fallen.” [31] As with so many frontal attacks on prepared positions throughout the war, valor alone could not overcome a well dug in enemy. “Negro troops proved that they could stop bullets and shell fragments as good as white men, but that was about all.” [32]

Despite the setback, the regiment went on to further actions where it continued to distinguish itself. The Northern press, particularly abolitionist newspapers brought about a change in the way that many Americans in the North, civilians as well as soldiers, saw blacks. The Atlantic Monthly noted, “Through the cannon smoke of that dark night, the manhood of the colored race shines before many eyes that would not see.” [33]

Frederick Douglass, who had two sons serving in the 54th Massachusetts, understood the importance of African Americans taking up arms against those that had enslaved them in order to win their freedom:

“Once let a black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S… let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pockets, and there is no power on earth which can deny he has won the right to citizenship in the United States.” [34]

Other African American units less famous than the illustrious 54th Massachusetts distinguished themselves in action against Confederate forces. Two regiments of newly recruited blacks were encamped at Milliken’s Bend Louisiana when a Confederate brigade attempting to relieve the Vicksburg garrison attacked them. The troops were untrained and ill-armed but held on against a determined enemy:

“Untrained and armed with old muskets, most of the black troops nevertheless fought desperately. With the aid of two gunboats they finally drove off the enemy. For raw troops, wrote Grant, the freedmen “behaved well.” Assistant Secretary of War Dana, still with Grant’s army, spoke with more enthusiasm. “The bravery of the blacks,” he declared, “completely revolutionized the sentiment in the army with regard to the employment of negro troops. I heard prominent officers who had formerly in private had sneered at the idea of negroes fighting express after that as heartily in favor of it.” [35]

The actions of the black units at Milliken’s bend attracted the attention and commendation of Ulysses Grant, who wrote in his cover letter to the after action report, “In this battle most of the troops engaged were Africans, who had little experience in the use of fire-arms. Their conduct is said, however, to have been most gallant, and I doubt not but with good officers that they will make good troops.” [36] They also garnered the attention of the press. Harper’s published an illustrated account of the battle with a “double-page woodcut of the action place a black color bearer in the foreground, flanked by comrades fighting hand-to-hand with Confederates. A brief article called it a “the sharp fight at Milliken’s bend where a small body of black troops with a few whites were attacked by a large force of rebels.” [37] In the South the result was chilling and shocked whites, one woman wrote “It is hard to believe that Southern soldiers – and Texans at that – have been whipped by a mongrel crew of white and black Yankees…. There must be some mistake.” While another woman in Louisiana confided in her diary, “It is terrible to think of such a battle as this, white men and freemen fighting with their slaves, and to be killed by such a hand, the very soul revolts from it, O, may this be the last.” [38]

By the end of the war over 179,000 African American Soldiers, commanded by 7,000 white officers served in the Union armies. For a number of reasons most of these units were confined to rear area duties or working with logistics and transportation operations. The policies to regulate USCT regiments to supporting tasks in non-combat roles “frustrated many African American soldiers who wanted a chance to prove themselves in battle.” [39] Many of the soldiers and their white officers argued to be let into the fight as they felt that “only by proving themselves in combat could blacks overcome stereotypes of inferiority and prove their “manhood.” [40] Even so in many places in the army the USCT and state regiments made up of blacks were scorned:

“A young officer who left his place in a white regiment to become colonel of a colored regiment was frankly told by a staff officer that “we don’t want any nigger soldiers in the Army of the Potomac,” and his general took him aside to say: “I’m sorry to have you leave my command, and am still more sorry that you are going to serve with Negroes. I think that it is a disgrace to the army to make soldiers of them.” The general added that he felt this way because he was sure that colored soldiers just would not fight.” [41]

The general of course, was wrong. In the engagements where USCT units were allowed to fight, they did so with varying success most often attributable to the direction of their senior officers. When given the chance they almost always fought well, even when badly commanded. This was true as well when they were thrown into hopeless situations. One such instance was when Ferrero’s Division, comprised of colored troops were thrown into the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg when “that battle lost beyond all recall.” [42] The troops advanced in good order singing as they went, while their commander, General Ferrero took cover in a dugout and started drinking; but the Confederate defenders had been reinforced and “Unsupported, subjected to a galling fire from batteries on the flanks, and from infantry fire in front and partly on the flank,” a witness write, “they broke up in disorder and fell back into the crater.” [43] Pressed into the carnage of the crater where white troops from the three divisions already savaged by the fighting had taken cover, the “black troops fought with desperation, uncertain of their fate if captured.” [44] In the battle Ferrero’s division lost 1327 of the approximately 4000 men who made the attack. [45]

Major General Benjamin Butler railed to his wife in a letter against those who questioned the courage of African American soldiers seeing the gallantry of black troops assaulting the defenses of Petersburg in September 1864: The man who says that the negro will not fight is a coward….His soul is blacker than then dead faces of these dead negroes, upturned to heaven in solemn protest against him and his prejudices.” [46]

The response of the Confederate government to Emancipation and African Americans serving as soldiers was immediate and uncompromisingly harsh. Davis approved of the summary executions of black prisoners carried out in South Carolina in November 1862, and a month later “on Christmas Eve, Davis issued a general order requiring all former slaves and their officers captured in arms to be delivered up to state officials for trial.” [47] Davis warned that “the army would consider black soldiers as “slaves captured in arms,” and therefore subject to execution.” [48] While the Confederacy never formally carried out the edict, there were numerous occasions where Confederate commanders and soldiers massacred captured African American soldiers.

The response of the Lincoln administration to send a note to Davis and threaten reprisals against Confederate troops if black soldiers suffered harm. It “was largely the threat of Union reprisals that thereafter gave African-American soldiers a modicum of humane treatment.” [49]

When captured by Confederates, black soldiers and their white officers received no quarter from many Confederate opponents. General Edmund Kirby Smith who held overall command of Confederate forces west of the Mississippi instructed General Richard Taylor to simply execute black soldiers and their white officers: “I hope…that your subordinates who may have been in command of capturing parties may have recognized the propriety of giving no quarter to armed negroes and their officers. In this way we may be relieved from a disagreeable dilemma.” [50] This was not only a local policy, but echoed at the highest levels of the Confederate government. In 1862 the Confederate government issued an order that threatened white officers commanding blacks: “any commissioned officer employed in the drilling, organizing or instructing slaves with their view to armed service in this war…as outlaws” would be “held in close confinement for execution as a felon.” [51] After the assault of the 54th Massachusetts at Fort Wagner a Georgia soldier “reported with satisfaction that the prisoners were “literally shot down while on their knees begging for quarter and mercy.” [52]

On April 12th 1864 at Fort Pillow, troops under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forrest massacred the bulk of over 231 Union most of them black as they tried to surrender. While it is fairly clear that Forrest did not order the massacre and even attempted to stop it, it was clear that he had lost control of his troops. Forrest’s soldiers fought with the fury of men possessed by hatred of an enemy that they considered ‘a lesser race’ and slaughtered the Union troops as they either tried to surrender or flee; but while Forrest did not order the massacre, he certainly was not displeased with the result. Ulysses Grant wrote that:

“These troops fought bravely, but were overpowered I will leave Forrest in his dispatches to tell what he did with them.

“The river was dyed,” he says, “with the blood of the slaughtered for up to 200 years. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed; but few of the officers escaped. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.” Subsequently Forrest made a report in which he left out the part that shocks humanity to read.” [53]

The bulk of the killing was directed at the black soldiers of the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, which composed over a third of the garrison. “Of the 262 Negro members of the garrison, only 58 – just over 20 percent – were marched away as prisoners; while of the 295 whites, 168 – just under sixty percent were taken.” [54] A white survivor of the 13th West Tennessee Cavalry, a Union unit at the fort wrote:

“We all threw down our arms and gave tokens of surrender, asking for quarter…but no quarter was given….I saw 4 white men and at least 25 negroes shot while begging for mercy….These were all soldiers. There were also 2 negro women and 3 little children standing within 25 steps of me, when a rebel stepped up to them and said, “Yes, God damn you, you thought you were free, did you?” and shot them all. They all fell but one child, when he knocked it in the head with the breech of his gun.” [55]

A Confederate Sergeant who was at Fort Pillow wrote home a week after the massacre: “the poor deluded negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy, but were ordered to their feet and shot down.” [56]

African American soldiers proved themselves during the war and their efforts paved the way for Lincoln and others to begin considering the full equality of blacks as citizens. If they could fight and die for the country, how could they be denied the right to votes, be elected to office, serve on juries or go to public schools? Under political pressure to end the war during the stalemate before Petersburg and Atlanta in the summer of 1864, Lincoln reacted angrily to Copperheads as well as wavering Republicans on the issue of emancipation:

“But no human power can subdue this rebellion without using the Emancipation lever as I have done.” More than 100,000 black soldiers were fighting for the Union and their efforts were crucial to northern victory. They would not continue fighting if they thought the North intended to betray them….If they stake their lives for us they must be prompted by the strongest motive…the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept…There have been men who proposed to me to return to slavery the black warriors. “I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will.” [57]

The importance of African Americans cannot be minimized, without them the war could have dragged on much longer or even ended in stalemate, which would have been a Confederate victory. Lincoln wrote about their importance in 1864:

“Any different policy in regard to the colored man, deprives us of his help, and this is more than we can bear. We can not spare the hundred and forty or hundred and fifty thousand now serving us as soldiers, seamen, and laborers. This is not a question of sentiment or taste, but one of physical force which may be measured and estimated as horse-power and Steam-power are measured and estimated. Keep it and you save the Union. Throw it away, and the Union goes with it.” [58]

Despite this, even in the North during and after the war, blacks, including former soldiers faced discrimination, sometimes that of the white men that they served alongside, but more often from those who did not support the war effort. Lincoln noted after the war:

“there will there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, the clenched teeth, the steady eye, the well poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.” [59]

Those rights would be fought for another century and what began in 1863 with the brave service and sacrifice of these African American soldiers began a process of increased civil rights that is still going on today. It would not be until after the war that some blacks were commissioned as officers in the Army. When Governor John Andrew, the man who had raised the 54th Massachusetts attempted to:

“issue a state commission to Sergeant Stephen Swails of the 54th…the Bureau of Colored Troops obstinately refused to issue Swails a discharge from his sergeant’s rank, and Swails promotion was held up until after the end of the war. “How can we hope for success to our arms or God’s blessing,” raged the white colonel of the 54th, Edward Hallowell, “while we as a people are so blind to justice?” [60]

The families of the free blacks who volunteered also suffered, especially those who still had families enslaved in Confederate occupied areas or Union States which still allowed slavery. One women in Missouri wrote her husband begging him to come home “I have had nothing but trouble since you left….They abuse me because you went & say they will not take care of our children & do nothing but quarrel with me all the time and beat me scandalously the day before yesterday.” [61]

However, the Emancipation Proclamation transformed the war, and even jaded White Union soldiers who had been against emancipation and who were deeply prejudiced against blacks began to change their outlook as the armies marched into the South and saw the horrors of slavery. Russell Weigley wrote that Union soldiers:

“confronting the scarred bodies and crippled souls of African Americans as they marched into the South experienced a strong motivation to become anti-slavery men…Men do not need to play a role long, furthermore, until the role grows to seem natural and customary to them. That of liberators was sufficiently fulfilling to their pride that soldiers found themselves growing more accustomed to it all the more readily.” [62]

But even more importantly for the cause of liberty, the sight of regiments of free African Americans, marching “through the slave states wearing the uniform of the U.S. Army and carrying rifles on their shoulders was perhaps the most revolutionary event of a war turned into revolution.” [63]

At peak one in eight Union troops were African American, and Black troops made an immense contribution to the Union victory. “Black troops fought on 41 major battlefields and in 449 minor engagements. Sixteen soldiers and seven sailors received Medals of Honor for valor. 37,000 blacks in army uniform gave their lives and untold sailors did, too.” [64]

Of the African American soldiers who faced the Confederates in combat, “deep pride was their compensation. Two black patients in an army hospital began a conversation. One of them looked at the stump of an arm he had once had and remarked: “Oh I should like to have it, but I don’t begrudge it.” His ward mate, minus a leg, replied: “Well, ‘twas [lost] in a glorious cause, and if I’d lost my life I should have been satisfied. I knew what I was fighting for.” [65]

After the war many of the African American soldiers became leaders in the African American community and no less than 130 held elected office including the U.S. Congress and various state legislatures. Sadly the nation has forgotten the efforts of the Free Black Soldiers and Sailors who fought for freedom, but even so the “contribution of black soldiers to Union victory remained a point of pride in black communities. “They say,” an Alabama planter reported in 1867, “the Yankees never could have whipped the South without the aid of the Negroes.” Well into the twentieth century, black families throughout the United States would recall with pride that their fathers and grandfathers had fought for freedom.” [66]

Notes

[1] Ibid. McPherson Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War p.101

[2] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.160

[3] Foner, Eric Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2005 p.45

[4] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.160

[5] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.313

[6] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.160

[7] Ibid. Goodwin Team of Rivals p.465

[8] Egnal, Marc Clash of Extremes: The Economic Origins of the Civil War Hill and Wang a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux New York 2009 p.318

[9] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.48

[10] Ibid. McPherson Tried by War p.159

[11] Ibid. McPherson Drawn With the Sword p.159

[12] McPherson, James M. Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford 1991 p.35

[13] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lighteningp.381

[14] Dobak, William Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 Skyhorse Publishing, New York 2013 p.10

[15] Ibid. McPherson Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution p.35

[16] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.31

[17] Ibid. Dobak Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 p.11

[18] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.31

[19] Ibid. Gallagher, Gary W. The Union War Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 2011 p.103

[20] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.34

[21] Glatthaar, Joseph T. Black Glory: The African American Role in Union Victory in Why the Confederacy Lost edited by Gabor S. Boritt Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1992

[22] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.686

[23] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.282

[24] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.379

[25] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Two p.398

[26] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.379

[27] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.686

[28] Ibid. McPherson Drawn With the Sword p.101

[29] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.686

[30] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening pp. 380-381

[31] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom pp.686-687

[32] Ibid. Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Two p.697

[33] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.686

[34] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 381

[35] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.634

[36] Trudeau, Noah Andre, Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War 1862-1865 Little, Brown and Company, Boston, New York and London, 1998 p.58

[37] Ibid. Gallagher The Union War p.97

[38] Ibid. Trudeau Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War 1862-1865 p.59

[39] Ibid. Gallagher The Union War p.92

[40] Ibid. McPherson Drawn With the Sword p.89 p.

[41] Catton, Bruce. A Stillness at Appomattox Doubleday and Company Garden City, New York 1953 p.227

[42] Ibid. Catton A Stillness at Appomattox p.249

[43] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Three Red River to Appomattox Random House, New York 1974 p.537

[44] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 pp.384-385

[45] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.537

[46] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.34

[47] Ibid. McPherson Battle Cry of Freedom p.566

[48] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p. 280

[49] Ibid. Weigley A Great Civil War p.188

[50] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 377

[51] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 377

[52] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.281

[53] Grant, Ulysses S. Preparing for the Campaigns of ’64 in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume IV, Retreat With Honor Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ pp.107-108

[54] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.111

[55] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 378

[56] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Three p.112

[57] Ibid. McPherson Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution p.89

[58] Ibid. Glatthaar Black Glory: The African American Role in Union Victory p.138

[59] Ibid. McPherson The War that Forged a Nation p. 113

[60] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p. 376

[61] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.282

[62] Ibid. Weigley A Great Civil War p.192

[63] Ibid. Weigley A Great Civil War p.191

[64] Gallagher, Gary, Engle, Stephen, Krick, Robert K. and Glatthaar editors The American Civil War: The Mighty Scourge of War Osprey Publishing, Oxford UK 2003 p.296

[65] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.36

[66] Ibid. Foner Forever Free p.55