Friends of Padre Steve’s World

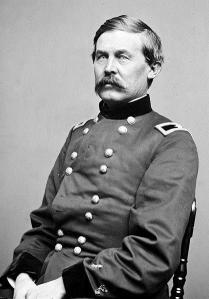

As I noted yesterday I am going to be posting about the Battle of Gettysburg for the next few days. All of these articles have appeared on my blog before and are part of my text on the Battle of Gettysburg which my agent is shopping to various publishers. This article is about the Union Cavalry commander, General John Buford who would lead a masterful delaying action against Confederate forces far superior to his small division on July 1st 1863.

Buford is a fascinating character, played to perfection by Sam Elliott in the movie Gettysburg he was one of the officers whose extraordinary leadership denied Lee a victory at Gettysburg, preserved the Union and led to the defeat of the Confederacy. I hope you enjoy this little piece about a most amazing man.

Peace

Padre Steve+

“He was decidedly the best cavalry general we had, and was acknowledged as such in the army, though being no friend to newspaper reporters…In many respects he resembled Reynolds, being rough in the exterior, never looking after his own comfort, untiring on the march and in the supervision of all the militia in his command, quiet and unassuming in his manners.” Colonel Charles Wainwright on Buford (Diary of Battle, p.309)

John Buford was born in Kentucky and came from a family with a long military history of military service, including family members who had fought in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. In fact according to some the family military pedigree reaches back to England’s War of the Roses.

Buford’s family was well off with a spacious plantation near Versailles on which labored forty-five slaves, and his father also established a stage line which carried “passengers and freight between Frankfort and Lexington.”His father divested himself of his property, selling his home, business and slaves and moved to Stephenson Illinois in 1838. [1] The young Buford developed an interest in military life which was enlivened by his half-brother Napoleon Bonaparte Buford who graduated from West Point in 1827, and his brother would be influential in helping John into West Point, which he entered in 1844.

Buford graduated with the class of 1848 which included the distinguished Union artilleryman John Tidball, and the future Confederate brigadier generals “Grumble Jones and “Maryland” Steuart. Among his best friends was Ambrose Burnside of the class of 1847. He did well academically but his conduct marks kept him from graduating in the top quarter of his class.

Upon graduation he was commissioned as a Brevet Second Lieutenant of Dragoons, however too late to serve in Mexico. Instead he was initially assigned to the First United States Dragoons but less than six months after joining was transferred to the Second Dragoons when he was promoted to full Second Lieutenant.

Instead of going to Mexico Buford “spent most of the 1850s tracking and fighting Indians on the Plains.” [2] During this period, the young dragoon served on the Great Plains against the Sioux, where he distinguished himself at the Battle of Ash Creek and on peacekeeping duty in the bitterly divided State of Kansas and in the Utah War of 1858.

His assignments alternated between field and staff assignments and he gained a great deal of tactical and administrative expertise that would serve him well. This was especially true in the realm of the tactics that he would employ so well at Gettysburg and on other battlefields against Confederate infantry and cavalry during the Civil War. Buford took note of the prevailing tactics of the day which still stressed a rigid adherence to outdated Napoleonic tactics which stressed mounted charges and “little cooperation with units of other arms or in the taking and holding of disputed ground.” [3] While he appreciated the shock value of mounted charges against disorganized troops he had no prejudice against “fighting dismounted when the circumstances of the case called for or seemed to justify it.” [4] Buford’s pre-war experience turned him into a modern soldier who appreciated and employed the rapid advances in weaponry, including the repeating rifle with tremendous effect.

Despite moving to Illinois Buford’s family still held Southern sympathies; his father was a Democrat who had opposed Abraham Lincoln. Buford himself was a political moderate and though he had some sympathy for slave owners:

“he despised lawlessness in any form – especially that directed against federal institutions, which he saw as the bulwark of democracy…..He especially abhorred the outspoken belief of some pro-slavery men that the federal government was their sworn enemy.” [5]

After the election of Abraham Lincoln, the officers of Buford’s regiment split on slavery. His regimental commander, Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, a Virginian and the father-in-law of J.E.B. Stewart announced that he would remain loyal to the Union, others like Beverly Robertson who would command a brigade of cavalry during the Gettysburg campaign resigned their commissions.

For many officers, both those who remained loyal to the Union and those who joined the Confederate cause the decision was often difficult, and many anguished over their decisions as they weighed their allegiance to the Union against their loyalty to home and family. Buford was not one of them.

Since Buford’s family had longstanding ties to Kentucky, the pro-secession governor of Kentucky, Beriah Magoffin offered Buford a commission in that states’ militia. At the time Kentucky was still an “undeclared border slave state” and Buford loyal to his oath refused the governor’s offer. He wrote a brief letter to Magoffin and told his comrades that “I sent him word that I was a Captain in the United States Army and I intend to remain one.” [6]Around the same time the new provisional government of the Confederacy “offered Buford a general officer’s commission, which reached him by mail at Fort Crittenden.” [7] According to Buford’s biographer Edward Longacre “a well-known anecdote has him wadding up the letter while angrily announcing that whatever future had in store he would “live and die under the flag of the Union.” [8]

However Buford’s family’s southern ties, and lack of political support from the few remaining loyal Kentucky legislators initially kept him from field command. Instead he received a promotion to Colonel and an assignment to the Inspector General’s Office, although it was not the field assignment that he desired it was of critical importance to the army in those early days of the war as the Union gathered its strength for the war. Buford was assigned to mustering in, and training the new regiments being organized for war. Traveling about the country he evaluated each unit in regard to “unit dress, deportment and discipline, the quality and quantity of weapons, ammunition, equipment, quarters, animals and transportation; the general health of the unit and medical facilities available to it; and the training progress of officers and men.” [9] Buford was a hard and devastatingly honest trainer and evaluator of the new regiments. He was especially so in dealing with commanding officers as well as field and company officers. Additionally he was a stickler regarding supply officers, those he found to be incompetent or less than honest were cashiered.

Buford performed these duties well but desired command. Eventually he got the chance when the politically well-connected but ill-fated Major General John Pope who “could unreservedly vouch for his loyalty wrangled for him command of a brigade of cavalry.” [10] After Pope’s disastrous defeat at Second Bull Run in August 1862 Buford was wounded in the desperate fighting at Second Manassas and returned to staff duties until January 1863 when he was again given a brigade. However, unlike many of the officers who served under Pope, Buford’s reputation as a leader of cavalry and field commander was increased during that campaign.

Buford was given the titular title of “Chief of Cavalry of the Army of the Potomac” by George McClellan, a title which sounded impressive but involved no command during the Antietam campaign. Following that frustrating task he continued in the same position under his old West Point friend Ambrose Burnside during the Fredericksburg campaign. Buford lost confidence in his old friend and was likely “shocked by his friend’s deadly ineptitude, his dogged insistence on turning defeat into nightmare.” [11]

When Burnside was relieved and Fighting Joe Hooker appointed to command the army, Buford’s star began to rise. While he was passed over by Hooker for command of the newly organized First Cavalry division in favor of Alfred Pleasanton who was eleven days his senior, he received command of the elite Reserve Brigade composed of mostly Regular Army cavalry regiments. When Major General George Stoneman was relieved of command following the Chancellorsville campaign, Pleasanton was again promoted over Buford.

In later years Hooker recognized that Buford “would have been a better man for the position of chief” [12] but in retrospect Buford’s pass over was good fortune for the Army of the Potomac on June 30th and July 1st 1863. Despite being passed over for the Cavalry Corps command, Buford, a consummate professional never faltered or became bitter. Despite the Pleasanton’s interference and “lax intelligence-gathering” [13] During the Gettysburg campaign he led his brigade well at Brandy Station as it battled J.E.B. Stuart’s troopers, after which he was recommended for promotion and given command of the First Cavalry division of the Cavalry Corps. [14]

Following Brandy Station Buford led his troopers aggressively as they battled Stuart’s troopers along the Blue Ridge at the battles of Aldie, Philmont, Middleburg and Upperville. It was at Upperville while fighting a hard action Confederate Brigadier general “Grumble Jones’s brigade that Buford’s troopers provided Hooker with the first visual evidence that Lee’s infantry was moving north into Maryland and Pennsylvania.

When Hooker was relieved on the night of June 27th and 28th George Meade gave Buford the chance at semi-independent command without Pleasanton looking over his shoulder. Meade appreciated Pleasanton’s administrative and organizational expertise and took him out of direct field command. Meade had his Cavalry Corps commander “pitch his tent next to his own on almost every leg of the trip to Pennsylvania and rarely let him out of sight or earshot.” [15]

One of Meade’s staff officers, Theodore Lyman gave this description of Buford:

“He is one of the best of the officers…and is a singular looking party. Figurez-vous a compactly built man of middle height, with a tawny mustache and a little, triangular gray eye, whose expression is determined, not to say sinister. His ancient corduroys are tucked into a pair of ordinary cowhide boots, his blue blouse is ornamented with holes; from which one pocket thereof peeps a huge pipe, while the other is fat with a tobacco pouch. Notwithstanding this get-up he is a very soldierly looking man. Hype is of a good natured disposition, but is not to be trifled with.” [16]

When he was ordered to screen the army as it moved into Pennsylvania, Buford was confident about his troopers and their ability and he and his men performed their duties admirably. On June 29th Buford’s men skirmished with two of Harry Heth’s regiments near the town of Fairfield, which Buford promptly reported to Meade and John Reynolds after ascertaining their size and composition.

The Battle of Gettysburg would be the zenith of Buford’s career. His masterful delaying action against Harry Heth’s division on July 1st 1863 enabled John Reynold’s wing of the army to arrive in time to keep the Confederates from taking the town and all of the high ground which would have doomed any union assault against them. Following Gettysburg Buford continued to command his cavalry leading his division in a number of engagements. In early November the worn out cavalryman who had been in so many actions over the past year came down with Typhoid. In hopes that he would recover he was told that he would be appointed to command all the cavalry in the West, however his health continued to decline. He was officially promoted to Major General of Volunteers by President Lincoln, over the objection of Secretary of War Stanton who disliked deathbed promotions. “Upon learning of the honor. Buford is supposed to have whispered, “I wish I could have lived now.” [17] He died later that evening, the last words warning his officers “patrol the roads and halt fugitives at the front.” [18]

John Pope wrote of Buford:

“Buford’s coolness, his fine judgment, and his splendid courage were well known of all men who had to do with him… His quiet dignity, covering a fiery spirit and a military sagacity as far reaching as it was accurate made him…one of the best and most trusted officers in the service.” [19]

Buford was buried at West Point and he is immortalized in the monument dedicated to him on McPherson’s Ridge at Gettysburg where he with binoculars in hand looks defiantly west in the direction of the advancing Confederates. The monument is surrounded by the gun tubes of four Union 3” Rifles, three of which were part of Lieutenant John Calef’s Battery which he directed on the fateful morning of July 1st 1863. He was portrayed masterfully portrayed by Sam Elliott in the movie Gettysburg.

Notes

[1] Longacre, Edward G. John Buford: A Military Biography Da Capo Press, Perseus Book Group, Cambridge MA p.17

[2] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[3] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.36

[4] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.36

[5] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.54

[6] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[7] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.70

[8] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.70

[9] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.78

[10] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[11] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.122

[12] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.44

[13] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.173

[14] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.64

[15] Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June-14 July 1863 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 1986 p.168

[16] Girardi, Robert I. The Civil War Generals: Comrades, Peers, Rivals in Their Own Words Zenith Press, MBI Publishing, Minneapolis MN 2013 p.38

[17] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.245

[18] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.246

[19] Ibid. Girardi The Civil War General p.38