Friends of Padre Steve’s World

For those that have followed my writing for some time you know that I teach military history and ethics at the Joint Forces Staff College. One of the great joys that I have is leading the Gettysburg Staff Ride, which is an optional event for students that want to participate. When I took the position here I took some of my older writings on Gettysburg and put them into a student study guide and text. That was two years ago. Then the text was about 70 pages long. It is now about 925 pages long and eventually I hope to get it published. When and if that happens I expect it to become two, and possibly three books.

This is the first of a series of articles that I will be posting potions of a chapter that I have rewritten about the critical battles on the south side of the battlefield on July 2nd 1863, the battle for Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, and the final repulse on Cemetery Ridge.

As you read this don’t just look at the events, but look at the people, and their reaction to the what they encountered on the battlefield, for that understanding of people is where we come to understand history.

So even if you are not a Civil War buff, or even a history buff, take the time to look at the people, their actions, and the things that made them who they were, and influenced what they did. History is about people.

So please enjoy,

Peace

Padre Steve+

Preparations

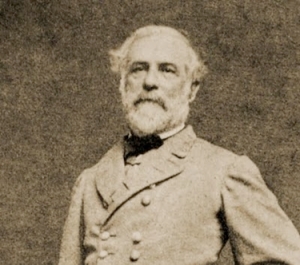

On July 2nd 1863 as on the first day of battle and throughout the Gettysburg campaign issues of command and control would be of paramount importance to both armies. On the second day the glaring deficiencies of Robert E Lee and his corps commanders command and control at Gettysburg would again be brought to the fore. Likewise the exemplary command of the Army of the Potomac by George Meade, Winfield Scott Hancock, staff artillery officer Henry Hunt and staff engineer Gouverneur Warren exemplified the best aspects of what we now define as Mission Command.

The definition of mission command as currently defined in American doctrine helps us in some ways to understand what happened on July 2nd 1863. Without imposing current doctrine on the leaders at Gettysburg, the definition describes the timeless aspect of leadership in battle and the importance of the human dynamic in war.

“Mission command is the conduct of military operations through decentralized execution based upon mission-type orders. Successful mission command demands that subordinate leaders at all echelons exercise disciplined initiative, acting aggressively and independently to accomplish the mission. Essential to mission command is the thorough knowledge and understanding of the commander’s intent at every level of command.” [1]

It is with this in mind that we look at the actions of various commanders during the critical second day of the battle of Gettysburg, and as we do so we also try to examine their lives and in a sense try to bring them to life. It is important because the actions of a number of commanders, including Robert E. Lee, George Meade, James Longstreet, Dan Sickles, and to a lesser degree A.P. Hill would be the subject of a great amount of controversy and partisan bickering that still lingers a century and a half later.

Confederate Consternation

Before the sun rose on July 2nd James Longstreet took stock of the situation. The burly commander of First Corps was now working to bring the divisions of McLaws and Hood from their bivouac sites west of Herr’s Ridge and onto the battlefield. While his divisions moved out, Longstreet met with Lee to again express his opposition to taking the offensive. He again brought up the subject of making a “broad turning movement around the enemy’s left flank that would place the Confederate army between the Federal capital and George Meade’s army.” [2] As he did the previous night, Lee again rebuffed Longstreet’s suggestion and apparently frustrated by Longstreet’s continued resistance to his decision Lee “walked off by himself, away from the conflict.” [3] Lee then left Longstreet and went to confer with Dick Ewell to discuss the possibility of attacking the Federal right, and he sent his staff topographical engineer, Captain Samuel Johnson to reconnoiter the Federal left.

At this point Lee had not yet decided where to attack. Again he conferred with Ewell about the possibility of attacking the Federal right, but Ewell again dissuaded him from doing so. Ewell insisted that a “daylight attack on Culp’s Hill or Cemetery Hill would be costly and of doubtful success.” [4] For a second time Lee brought up the possibility of Ewell redeploying his corps from its positions around the “fishhook” of the Federal line to the west where they could better support an assault on the Federal left, but as he had the previous night “Ewell persuaded the general commanding to leave his corps where it was.” [5] In doing so Ewell promised to create a demonstration on the Federal right when he heard Longstreet’s attack commence. But, “according to Fitzhugh Lee, He decided to turn Meade’s left with Longstreet’s corps, demonstrate against his centre and right with Hill’s and Ewell’s corps, and then convert this demonstration into a real attack directly Longstreet’s attack succeeded.” [6] Ewell’s corps was to be the “anvil against which Longstreet would smash whatever was left of the 1st and 11th Corps, or any other Union reinforcements might have arrived overnight.” [7] However, the position of Second Corps around the fishhook was a poor position. “It greatly extended the army’s lines, and confronted the most defensible part of the Federal lines.” [8] Likewise, the position offered little advantage for Ewell’s artillery.

By the time Lee returned to his headquarters the divisions of Hood and McLaws, with the exception of Law’s brigade of Hood’s division, “which had been “left by Hood on picket” below the pike stretching back to Chambersburg, and was far behind the others” [9] were marching onto the field and halted just west of Seminary Ridge while the Confederate leaders conferred. But Longstreet was also troubled by the absence of George Pickett’s division of Virginians, which due to the lack of cavalry had been left at Chambersburg to guard the Confederate supply trains and would not be available for action until late in the evening.

Captain Johnson returned to the headquarters following his reconnaissance of the Federal left. He reported that the Federal left was weakly held and that there were no Federal troops on the Round Tops. But Johnson’s reconnaissance was not nearly as thorough or accurate as he reported. Johnson made “no detailed sketches of the hazardously rough ground at the southern end of the Federal line” and gave “an inadequate picture of the obstacles to mass troop movement.”[10] Despite getting up to the Round Tops he did not observe the large number of Union troops from Sickles’ Third Corps in the woods to the north and northwest of Little Round Top. The latter omission appears to be more to bad timing, lack of attention, Johnson’s lack of familiarity with the terrain and lack of experience in conducting a reconnaissance that should have been undertaken by cavalry scouts.

Johnson arrived with his report as Lee was conferring with Hill and Longstreet. He traced his route on the map. Johnson’s replies to Lee’s questions satisfied Lee that the Federal left was again up in the air and unprotected as it had been at Chancellorsville. However, this was not the case. First, had Johnson taken the route that he described he “would have come upon the encampments of the Third Corps, located north and west of Little Round Top. He would have also encountered trouble from John Buford’s cavalry vedettes, some of whom were posted about Sherfy’s peach orchard.” [11] Johnson claimed to have gotten up to Little Round Top, and if he did the only way he could not have seen Federal troops was if he had gotten there “just after the guarding troops of the night had been withdrawn and just before their replacements had arrived.” [12] Even if that was the case it would have been hard for Johnson to miss the Third Corps troop bivouacs. The Federals might have been obscured from the Captain’s view by the morning mist, but “Johnson should have detected the noise of men and animals, drums and bugles.” [13] A more likely scenario is that the inexperienced Johnson went further south and scaled Big Round Top from which his report of seeing no troops would have been completely accurate, but the inaccuracies of Johnson’s report were to cause serious complications and consequences for Lee’s plan.

Johnson’s report convinced Lee of the soundness of his plan to roll up the Federal left. He again conferred with Longstreet and announced his intention to attack Meade’s left flank with Hood and McLaws divisions. Lee went directly to McLaws and described his plan. He desired McLaws division to move south to a position perpendicular to the Emmitsburg Road south of the Peach Orchard. McLaws said it was possible but wanted to make a personal reconnaissance and Longstreet objected to the position that Lee indicated for McLaws division. Longstreet said “No, sir, I do not want wish for you to leave your division,” and tracing with his finger a line perpendicular to that drawn on the map, said, “I wish your division placed so.” “No, General,” Lee objected, “I wish it placed just so.” [14] Lee’s statement ended the conversation and after another consult with Ewell, Lee returned to lay out his plan. As he left for his division McLaws recalled that “General Longstreet appeared if he was irritated and annoyed,… but the cause I did not ask.” [15]

The divisions of Hood and McLaws were still about a mile and a half to the rear of the Confederate line. As soon as those divisions were in position they would march south while attempting to remain unseen by Federal troops on the high ground to the east, and then wheel left and come up the Emmitsburg Road into what Lee believed was the rear of the Federal position. After his brief consultation with Ewell regarding the security of his left flank, Lee returned to check the progress of Longstreet. Longstreet had not been completely inactive. He had already sent out his artillery led by Porter Alexander to find a suitable position to support the impending attack, but he did not make any further consultations with Hood of McLaws, nor send any officers to make a further reconnaissance until receiving definitive orders from Lee to launch the attack. For some reason, perhaps his misunderstanding with Lee concerning the nature of the campaign, or Lee’s rejection of his course of action, Longstreet did not demonstrate his usual energy and the careful preparation that he showed in previous actions. His biographer, Jeffry Wert noted “He allowed his disagreement with Lee to affect his conduct….The concern for detail, the regard for timely information, and the need for preparation were absent. Or, as Moxley Sorrell admitted, “there was apparent apathy in his movements. They lacked the fire and point of his usual bearing on the battlefield.” [16]

Like all movements to contact made by large armies was fraught with logistical complications and irritating, yet unavoidable delays in moving large numbers of troops over unfamiliar terrain. Even if Longstreet had acted with greater alacrity, and if the Confederates at all levels had been more efficient managers, “it would take several hours for to march them a distance of four miles or more to the place where they would be deployed for battle.” [17] Lee desired for McLaws division to lead the assault. However, McLaws division was trailing Hood’s troops on the Chambersburg Pike west of town, and would have to pass around Hood’s division to take up its position in the Confederate van. Another delay occurred when Longstreet requested additional time for Law’s brigade of Hood’s division, marching up from Guilford to rejoin Hood before he began his movement. Lee acquiesced to Longstreet and Law’s men reached Hood about an hour later.

Lee’s plan required that Anderson’s division of Hill’s Corps would have to move first to take up a supporting position along Seminary Ridge so it could launch a supporting attack as Longstreet’s corps advanced up the Emmitsburg Road. However, elements of Anderson’s division had become embroiled in a firefight at the Bliss farm which delayed his movement to reach his start position for the attack. But in addition to this, lee complicated matters by not removing Anderson from Hill’s command and giving Longstreet operational control. Instead Lee, possibly to avoid hurting the “sensitive Hill by removing a division that had not yet fought with his corps, and yet allow Longstreet to call on Anderson without going through Hill, Lee instructed Anderson “to cooperate…in Longstreet’s attack.” [18] It was another example of Lee’s vague orders which plagued the campaign, as one historian observed, “This order was the vaguest he ever gave. He did not specify whether Anderson was to act under the orders of Longstreet, or of Hill. His new corps commander, or Lee’s own. He seemed to be reverting to the loose structure of his early days in command.” [19]

But even more importantly it was an offensive that required “careful coordination and expert timing. If his plan was sound, which is debatable, there was still the question of whether the army was equal to the task.” [20]

As the various Confederate commands struggled to get in position to attack, without being observed, the Army of the Potomac readied itself for action. After the near disaster of July 1st, the army had recovered its “operational balance, setting in place the systems necessary for command and control.” [21] Meade and his subordinates had chosen a strong position from which they could maximize their strengths, and in addition to this they ensured that each corps had established headquarters and reported their position to the army staff. Wireless was set up to allow Meade to communicate directly to Washington, while the army’s Signal Corps detachments set up observation points on every bit of high ground under Federal control, including Little Round Top, which allowed them communicate with Meade’s headquarters by semaphore. Meanwhile, Henry Hunt had brought up the reserve artillery and began refitting damaged guns while supervising the emplacement of newly arrived batteries along the Federal line. Even more importantly, unlike Lee whose exterior lines refusal to use semaphore created undue delays in communications, Meade’s little headquarters at the Leister house was “almost up to the line of battle and little time would be wasted in the transmittal of orders.” [22]

Meade’s Defensive Preparation

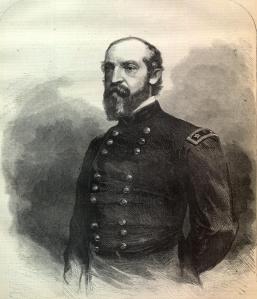

On the morning of July 2nd the Army of the Potomac was mostly assembled on the high ground from Culp’s Hill to Cemetery Hill and along Cemetery Ridge. In the north and east, the Twelfth Corps under the command of Major General Henry Slocum held Culp’s Hill and protected the Federal right. His troops began fortifying the already formidable position as soon as they arrived on the night of July 1st and continued to strengthen their positions throughout the day.

The battered remnants of the First and Eleventh Corps held Cemetery Hill where they had made their final stand on the night of July 1st. Oliver Howard retained command of Eleventh Corps, while Meade returned Doubleday to command of his division and brought John Newton from Sixth Corps to command the remnants of the battered First Corps. Winfield Scott Hancock’s crack Second Corps extended the line down southward down Cemetery Ridge. To Second Corps right was Dan Sickles’ Third Corps. George Sykes Fifth Corps was in reserve just to the north and east of Little Round Top, while John Sedgwick’s massive Sixth Corps was still enroute, marching up the Baltimore Pike. “The convex character of the Union line facilitated the rapid movement of troops to reinforce any threatened section.” [23] Unlike Lee’s troops who had to make long marches to support each other, the Union men “never had to march more than two and half miles, usually less.” [24]This would provide Meade with a vital advantage during the viscous battle that was to ensue on July 2nd and as the ever observant Porter Alexander noted, “Communication between our flanks was very long – roundabout & slow while the enemy were practically all in one convenient sized bunch. Reinforcements from their extreme right marched across in ample time to repulse our attack on their extreme left. But Ewell’s men could hardly have come to our help in half a day – & only under view & fire.” [25]

The Army of the Potomac now occupied a solid and well laid out position which commanded the battlefield. Meade and Warren were worried that Lee might attempt to turn them out of their position by moving south, as Longstreet was begging Lee to do, but in reality there was little threat. Even so, Major General Gouverneur Warren, the Army’s Staff Engineer Officer who had been sent by Meade to assist Hancock the night of the first wrote his wife that morning: “we are now all in line of battle before the enemy in a position where we cannot be beaten but fear being turned.” [26]

There was one notable problem, the commander of the Third Corps, Major General Dan Sickles did not like the position assigned to his corps on the south end of Cemetery Ridge.

To be continued…

Notes

[1] __________ Mission Command White Paper and JP 3-31

[2] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 pp. 260-261

[3] Thomas, Emory Robert E. Lee W.W. Norton and Company, New York and London 1995 p.297

[4] Pfanz, Donald. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier’s Life University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 1998 p.315

[5] Sears, Stephen Gettysburg Houghton Mifflin Company Boston and New York 2004 p.256

[6] Fuller, J.F.C. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1957 p.197

[7] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.236

[8] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.256

[9] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg The Last Invasion p.237

[10] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.186

[11] Trudeau, Noah Andre Gettysburg a Testing of Courage Perennial Books, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.289

[12] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.186

[13] Ibid. Wert General James Longstreet p.262

[14] Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg the Second Day University of North Carolina Press, Charlotte and London, 1987 p.110

[15] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.290

[16] Ibid. Wert General James Longstreet p.268

[17] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York 1968 p.376

[18] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.193

[19] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.193

[20] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.384

[21] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.292

[22] Cleaves, Freeman Meade of Gettysburg University of Oklahoma Press, Norman and London 1960 p.142

[23] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command p.332

[24] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command p.332

[25] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p242

[26] Jordan, David M. Happiness is Not My Companion: The Life of G.K. Warren Indiana University Press, Bloomington Indiana 2001 p.89