Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

This week I have been relating religion to civil rights through the lens of the slavery, abolition, and the ante-bellum United States and today I will continue that with another section of my Civil War and Gettysburg Staff Ride text. It comes from the same chapter as my past few posts dealing with the role of religion and ideology in the period and its effect on the antagonists before, during and after the war.

It is a lens through which we can view other topics that divide us today including the continuing battle against racism, Women’s rights and Gay rights. The fact is that we cannot isolate these issues from the understanding that the defense of liberty for all safeguards liberty for all. Sadly, there are a substantial number of Christians in the United States who do not believe that and through the legislative process seek to limit, role back, or completely deny rights to groups that they despise, especially Gays, but also women, and racial and religious minorities. We cannot get around that fact. It is happening with new instances occurring almost every week, and much of these laws are being passed due to the “sincerely held religious beliefs” of Christians to deny other people’s rights based on their interpretation of Biblical texts.

The words of the current politicians, preachers and pundits who fight to limit the rights of others is strikingly similar to those who defended slavery and attacked those who fought against it.

This is not new, it has happened many times in our history, but the most notorious and injurious to American society was the defense of the institution of Slavery by American Christians, particularly those in the South. This article discusses that defense of slavery which arose in response to the tiny, but vocal number of Christians who helped lead the abolition movement.

Have a great day,

Peace

Padre Steve+

Southern Religious Support of Slavery

“we must go before the nation with the Bible as the text and ‘Thus saith the Lord’ as the answer….we know that on the Bible argument the abolition party will be driven to reveal their true infidel tendencies. The Bible being bound to stand on our side…” Reverend Robert Lewis Dabney on defending slavery and condemning its critics

In light of the threat posed to slavery by the emerging abolitionist movement, slaveholders were forced to shift their defense of slavery away from it being simply a necessary evil to a positive good. The institution of slavery became “in both secular and religious discourse, the central component of the mission God had designed for the South.” [1] Like in the North where theology was at the heart of many abolitionist arguments, in the South theology was used to enshrine and defend the institution of slavery. British Evangelical-Anglican theologian Alister McGrath notes how “the arguments used by the pro-slavery lobby represent a fascinating illustration and condemnation of how the Bible may be used to support a notion by reading the text within a rigid interpretive framework that forces predetermined conclusions to the text.” [2]

Southern religion was a key component of something bigger than itself and played a role in the development of an ideology much more entrenched in the Southern culture than the abolitionist cause did in the North. This was in large part due to the same Second Great Awakening that brought abolitionism to the fore in the North. “Between 1801 when he Great Revival swept the region and 1831 when the slavery debate began, southern evangelicals achieved cultural dominance in the region. Looking back over the first thirty years of the century, they concluded that God had converted and blessed their region.” [3] The Southern ideology which enshrined slavery as a key component of all areas of life was a complete worldview, a system of values, culture, religion and economics, or to use the more modern German term “Weltanschauung.” The Confederate worldview was the Cause. As Emory Thomas wrote in his book The Confederate Nation:

“it was the result of the secular transubstantiation in which the common elements of Southern life became sanctified in the Southern mind. The South’s ideological cause was more than the sum of its parts, more than the material circumstances and conditions from which it sprang. In the Confederate South the cause was ultimately an affair of the viscera….Questions about the Southern way of life became moral questions, and compromises of Southern life style would become concession of virtue and righteousness.” [4]

Despite the dissent of some, the “dominant position in the South was strongly pro-slavery, and the Bible was used to defend this entrenched position.” [5] This was tied to a strongly Calvinistic theology which saw slavery in context with the spread of the evangelical Protestant faith that had swept through the South as slavery spread. For many, if not most Southern ministers “the very spread of evangelical religion and slave labor in the South was a sign of God’s divine favor. Ministers did not focus on defending slavery in the abstract but rather championed Christian slaveholding as it was practiced in the American South. Though conceding that some forms of slavery might be evil, Southern slavery was not.” [6]

The former Governor of South Carolina, John Henry Hammond, led the religiously based counter argument to the abolitionists. Hammond’s arguments included biblical justification of blacks being biologically inferior to whites and slavery being supported in the Old Testament where the “Hebrews often practiced slavery” and in the New testament where “Christ never denounced servitude.” [7] Hammond warned:

“Without white masters’ paternalistic protection, biologically inferior blacks, loving sleep above all and “sensual excitements of all kinds when awake” would first snooze, then wander, then plunder, then murder, then be exterminated and reenslaved.” [8]

Others in the South, including politicians, pundits and preachers were preaching “that slavery was an institution sanction by God, and that even blacks profited from it, for they had been snatched out of pagan and uncivilized Africa and been given the advantages of the gospel.” [9] The basic understanding was that slavery existed because “God had providential purposes for slavery.” [10]

At the heart of the pro-slavery theological arguments was in the conviction of most Southern preachers of human sinfulness. “Many Southern clergymen found divine sanction for racial subordination in the “truth” that blacks were cursed as “Sons of Ham” and justified bondage by citing Biblical examples.” [11] But simply citing scripture to justify the reality of a system of which they reaped the benefit, is just part of the story. The real issue was far greater than that. The theology that justified slavery also, in the minds of many Christians in the north justified what they considered “the hedonistic aspects of the Southern life style.” [12] This was something that abolitionist preachers continually emphasized, criticizing the greed, sloth and lust inherent in the culture of slavery and plantation life, and was an accusation of which Southern slaveholders, especially evangelicals took umbrage, for in their understanding good men could own slaves. Their defense was rooted in their theology. The hyper-individualistic language of Southern evangelicalism gave “new life to the claim that good men could hold slaves. Slaveholding was a traditional mark of success, and a moral defense of slavery was implicit wherever Americans who considered themselves good Christians held slaves.” [13] The hedonism and fundamentalism that existed in the Southern soul, was the “same conservative faith which inspired John Brown to violence in an attempt to abolish slavery…” [14]

Slave owners frequently expressed hostility to independent black churches and conducted violence against them, and “attacks on clandestine prayer meetings were not arbitrary. They reflected the assumption (as one Mississippi slave put it) “that when colored people were praying [by themselves] it was against them.” [15] But some Southern blacks accepted the basic tenets of slave owner-planter sponsored Christianity. Frederick Douglass later wrote “many good, religious colored people who were under the delusion that God required them to submit to slavery and wear their chains with weakness and humility.” [16]

The political and cultural rift began to affect entire church denominations. The heart of the matter went directly to theology, in this case the interpretation of the Bible in American churches. The American Protestant and Evangelical understanding was rooted in the key theological principle of the Protestant Reformation, that of Sola Scripura, which became an intellectual trap for northerners and southerners of various theological stripes. Southerners believed that they held a “special fidelity to the Bible and relations with God. Southerners thought abolitionists either did not understand the Bible or did not know God’s will, and suspected them of perverting both.” [17]The problem was then, as it is now that:

“Americans favored a commonsense understanding of the Bible that ripped passages out of context and applied them to all people at all times. Sola scriptura both set and limited terms for discussing slavery and gave apologists for the institution great advantages. The patriarchs of the Old Testament had owned slaves, Mosaic Law upheld slavery, Jesus had not condemned slavery, and the apostles had advised slaves to obey their masters – these points summed up and closed the case for many southerners and no small number of northerners.” [18]

In the early decades of the nineteenth century there existed a certain confusion and ambivalence to slavery in most denominations. The Presbyterians exemplified this when in 1818 the “General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, while opposing slavery against the law of God, also went on record as opposing abolition, and deposed a minister for advocating abolition.” [19] There were arguments by some American Christians including some Catholics, Lutherans, Episcopalians and others to offer alternative ways to “interpreting and applying scripture to the slavery question, but none were convincing or influential enough to force debate” [20] out of the hands of literalists.

However the real schisms between the Northern and Southern branches of the major denominations which began to emerge in the mid to late 1830s continued to grow with the actual breakups of the major denominations coming in the 1840s. The first denomination to split were the Methodists. This occurred in 1844 when “the Methodist General Conference condemned the bishop of Georgia for holding slaves, the church split and the following year saw the birth of the Methodist Episcopal Church.” [21] Not all Methodists in the South agreed with this split and a few Methodist abolitionists in the South “broke away from mainline Methodism to form the Free Methodist Church.” [22]

The Baptists were next, when the Foreign Mission Board “refused to commission a candidate who had been recommended by the Georgia Baptist Convention, on the ground that he owned slaves” [23] resulting in the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention. The Baptist split is interesting because until the early 1800s there existed a fairly strong anti-slavery movement in states such as Kentucky, while in 1790 the General Committee of Virginia “adopted a statement calling slavery “a violent deprivation of the rights of nature, and inconsistent with a republican government; and therefore [we] recommend it to our brethren to make use of every legal measure, to extirpate the horrid evil from the land.” [24]

However, in many parts of the Deep South there existed no such sentiment and in South Carolina, noted Baptist preachers including “Richard Furman, Peter Bainbridge, and Edmund Botsford were among the larger slaveholders.” [25] Furman wrote a defense of slavery in 1822 where he made the argument that “the right of holding slaves is clearly established in the Holy Scriptures by precept and example.” [26] After a number of slave uprisings, including the Nat Turner Revolt in Virginia, pro-slavery voices “tended to silence any remaining antislavery voices in the South.” [27]

These voices grew more ever more strident and in 1835 the Charleston Association “adopted a militant defense of slavery, sternly chastising abolitionists as “mistaken philanthropists, and denuded and mischievous fanatics.” [28] Those who met in Augusta Georgia to found the new Southern Baptist Convention indicated that “the division was “painful” but necessary because” our brethren have pressed upon every inch of our privileges and our sacred rights.” [29] Since the Baptist split was brought about by the refusal of the Triennial Convention to appoint slaveholders as foreign missionaries the new convention emphasized the theological nature of their decision:

“Our objects, then, are the extension of the Messiah’s kingdom, and the glory of God. Not disunion with any of his people; not the upholding of any form of civil rights; but God’s glory, and Messiah’s increasing reign; in the promotion of which, we find no necessity for relinquishing any of our civil rights. We will never interfere with what is Caesar’s. We will not compromit what is God’s.” [30]

Of course, to the Baptists who met at Augusta, “what was Caesar’s” was obviously the institution of slavery.

The last denomination to officially split was the Presbyterians in 1861 who, “reflecting the division of the nation, the Southern presbyteries withdrew from the Presbyterian Church and founded their own denomination.” [31] The split in the Presbyterian Church had been obvious for years despite their outward unity. Some Southern pastors and theologians were at the forefront of battling their northern counterparts for the theological high ground that defined just whose side God was on. James Henley Thornwell presented the conflict between northern evangelical abolitionists and southern evangelical defenders of slavery in Manichean terms. He believed that abolitionists attacked religion itself.

“The “parties in the conflict are not merely abolitionists and slaveholders,…They are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, Jacobins, on one side, and friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battle ground – Christianity and Atheism as the combatants; and the progress of humanity at stake.” [32]

Robert Lewis Dabney, a southern Presbyterian pastor who later served as Chief of Staff to Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign and at Seven Pines and who remained a defender of slavery long after the war was over wrote that:

“we must go before the nation with the Bible as the text and ‘Thus saith the Lord’ as the answer….we know that on the Bible argument the abolition party will be driven to reveal their true infidel tendencies. The Bible being bound to stand on our side, they have to come out and array themselves against the Bible. And then the whole body of sincere believers at the North will have to array themselves, though unwillingly, on our side. They will prefer the Bible to abolitionism.” [33]

Southern churches and church leaders were among the most enthusiastic voices for disunion and secession. They labeled their Northern critics, even fellow evangelicals in the abolition movement as “atheists, infidels, communists, free-lovers, Bible-haters, and anti-Christian levelers.” [34] The preachers who had called for separation from their own national denominations years before the war now “summoned their congregations to leave the foul Union and then to cleanse their world.” [35] Thomas R.R. Cobb, a Georgia lawyer, an outspoken advocate of slavery and secession who was killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg, wrote proudly that Secession “has been accomplished mainly by the churches.” [36]

The Reverend William Leacock of Christ Church, New Orleans declared in his Thanksgiving sermon:

“Our enemies…have “defamed” our characters, “lacerated” our feelings, “invaded “our rights, “stolen” our property, and let “murderers…loose upon us, stimulated by weak or designing or infidel preachers. With “the deepest and blackest malice,” they have “proscribed” us “as unworthy members… of the society of men and accursed before God.” Unless we sink to “craven” beginning that they “not disturb us,…nothing is now left us but secession.” [37]

The fact that so many Protestant ministers, intellectuals, and theologians, not only Southerners, but men like “Princeton’s venerable theologian Charles B. Hodge – supported the institution of slavery on biblical grounds, often dismissing abolitionists as liberal progressives who did not take the Bible seriously” leaves a troubling question over those who claim to oppose issues on supposedly Biblical grounds. Such men in the North spoke out for it “in order to protect and promote interests concomitant to slavery, namely biblical traditionalism, and social and theological authority.” [38] The Northern clerical defenders of slavery perceived the spread of abolitionist preaching as a threat, not just to slavery “but also to the very principle of social and ecclesiastical hierarchy.” [39] Alistair McGrath asks a very important question for modern Christians who might be tempted to support a position for the same reasons today, “Might not the same mistakes be made all over again, this time over another issue?” [40]

Notes

[1] Gallagher, Gary W. The Confederate War: How Popular Will, Nationalism and Military Strategy Could not Stave Off Defeat Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 1999 p.67

[2] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[3] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.69

[4] Thomas, Emory The Confederate Nation 1861-1865 Harper Perennial, New York and London 1979 p.4

[5] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[6] Ibid. Varon Disunion! p.109

[7] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.29

[8] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.29

[9] Gonzalez, Justo L. The History of Christianity Volume 2: The Reformation to the Present Day Harper and Row Publishers San Francisco 1985 p.251

[10] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.54

[11] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.22

[12] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.22

[13] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.30

[14] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.22

[15] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.116

[16] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.116

[17] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.60

[18] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.14

[19] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[20] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.14

[21] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[22] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[23] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[24] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.383

[25] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[26] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[27] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[28] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[29] Shurden, Walter B Not a Silent People: The Controversies that Have Shaped Southern Baptists Broadman Press, Nashville TN 1972 p.58

[30] Ibid. Shurden Not a Silent People p.58

[31] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[32] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.13

[33] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.14

[34] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.97

[35] Freehling, William. The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2007 p.460

[36] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.39

[37] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II p.462

[38] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.38

[39] Ibid. Varon Disunion! P.108

[40] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

The Desegregation of Baseball and Its Importance Today

John Jorgensen, Pee Wee Reese, Ed Stanky and Jackie Robinson on opening day 1947

“Jackie, we’ve got no army. There’s virtually nobody on our side. No owners, no umpires, very few newspapermen. And I’m afraid that many fans will be hostile. We’ll be in a tough position. We can win only if we can convince the world that I’m doing this because you’re a great ballplayer, a fine gentleman.” Branch Rickey to Jackie Robinson

My friends, in just a few days pitchers and catchers report for the 2015 Baseball Spring Training and it is time to reflect again on how Branch Rickey’s signing of Jackie Robinson helped advance the Civil Rights of Blacks in the United States. What Rickey did was a watershed, and though it took time for every team in the Major Leagues to integrate, the last being the Boston Red Sox in 1959, a dozen years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier.

Branch Rickey shook the foundations of America when he signed Jackie Robinson to a Major League deal in 1947, a year before President Truman desegregated the military and years before Jim Crow laws were overturned in many states.

Robinson and the early pioneers of the game did a service to the nation. They helped many white Americans see that Blacks were not only their equals as human beings, and as it was note about Ernie Banks and others that soon “little white boys wanted to grow up and be Ernie Banks.”

Charles Thomas

But for Rickey the crusade to integrate baseball began long before 1947. In 1903, Rickey, then a coach for the Ohio Wesleyan University baseball team had to console his star player, Charles Thomas when a hotel in South Bend Indiana refused him a room because he was black. Rickey found Thomas sobbing rubbing his hands and repeating “Black skin. Black skin. If only I could make them white.” Rickey attempted to console his friend saying “Come on, Tommy, snap out of it, buck up! We’ll lick this one day, but we can’t if you feel sorry for yourself.”

The Young Branch Rickey

Thomas, encouraged by Rickey was remembered by one alumnus who saw a game that Thomas played in noted that “the only unpleasant feature of the game was the coarse slurs cast at Mr. Thomas, the catcher.” However, the writer noted something else about Thomas that caught his eye: “But through it all, he showed himself far more the gentleman than his insolent tormentors though their skin is white.”

Baseball like most of America was not a place for the Black man. Rickey, a devout Christian later remarked “I vowed that I would always do whatever I could to see that other Americans did not have to face the bitter humiliation that was heaped upon Charles Thomas.”

In April 1947 Rickey, now the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers had one African-American ballplayer at the Dodgers’ Spring Training site in Daytona Beach Florida. The South was still a hotbed of racial prejudice, Jim Crow was the law of the land and Blacks had no place in White Man’s baseball. That player was Jackie Robinson.

Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey

The Dodgers had been coming to Florida for years. Rickey moved the Dodgers from Jacksonville to Daytona Beach in 1947 after Jacksonville had refused to alter its segregation laws to allow an exhibition game between the Dodgers International League affiliate the Montreal Royals, for whom Robinson starred.

That was the year that Rickey signed Robinson to a minor league contract with the Royals. When Rickey called up Robinson 6 days prior to the 1947 season, it was Robinson broke the color barrier for the Dodgers and Major League Baseball. However it would take another 12 years before all Major League teams had a black player on their roster.

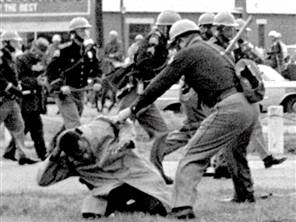

It is hard to imagine now that even after Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier that other teams did not immediately sign black players. However Rickey and Robinson broke the color barrier a year before Harry Truman had integrated the Armed Forces and seven years before the Supreme Court ruled the segregation of public schools illegal. But how could that be a surprise? The country was still rampant with unbridled racism. Outside of a few Blacks in the military and baseball most African Americans had few rights. In the North racism regulated most blacks to ghettos, while in the South, Jim Crow laws and public lynchings of progressive or outspoken Blacks.

But Jackie Robison and Branch Rickey helped bring about change, and soon other teams were following suit.

Larry Doby (above) and Satchel Paige signed by the Indians

The Cleveland Indians under their legendary owner Bill Veeck were not far behind the Dodgers in integrating their team. They signed Larry Doby on July 5th 1947. Doby would go on to the Hall of Fame and was a key player on the 1948 Indian team which won the 1948 World Series, the last that the storied franchise has won to this date.

Hank Thompson and Roy Campanella

The St. Louis Browns signed Third Baseman Hank Thompson 12 days after the Indians signed Doby. But Thompson, Robinson and Doby would be the only Blacks to play in that inaugural season of integration. They would be joined by others in 1948 including the immortal catcher Roy Campanella who signed with the Dodgers and the venerable Negro League pitcher, Satchel Paige who was signed by the Indians.

Monte Irvin (Above) and Willie Mays

It was not until 1949 when the New York Giants became the next team to integrate. They brought up Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson who they had acquired from the Browns. In 1951 these men would be joined by a young, rookie Willie Mays to become the first all African-American outfield in the Major Leagues. Both Mays and Irvin would enter the Hall of Fame and both are still a key part of the Giants’ story. Despite their age have continued to be active in with the Giants and Major League Baseball.

Samuel “the Jet” Jethroe

The Boston Braves were the next to desegregate calling up Samuel “the Jet” Jethroe to play Center Field. Jethroe was named the National League Rookie of the Year in 1950.

Minnie Minoso

In 1951 the Chicago White Sox signed Cuban born Minnie Minoso who had played for Cleveland in 1949 and 1951 before signing with the White Sox. Minoso would be elected to 9 All-Star teams and win 3 Golden Gloves.

Ernie Banks (above) and Bob Trice

The Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Athletics integrated at the end of the 1953 season. The Cubs signed Shortstop Ernie Banks who would go on to be a 14 time All-Star, 2 time National League MVP and be elected to the Hall of Fame in 1977 on the first ballot. The Athletics called up pitcher Bob Trice from their Ottawa Farm team where he had won 21 games. Trice only pitched in 27 Major League games over the course of three seasons with the Athletics.

Curt Roberts

Four teams integrated in 1954. The Pittsburgh Pirates acquired Second Baseman Curt Roberts from Denver of the Western League as part of a minor league deal. He would play 171 games in the Majors. He was sent to the Columbus Jets of the International League in 1956 and though he played in both the Athletics and Yankees farm systems but never again reached the Majors.

Tom Alston

The St. Louis Cardinals, the team that had threatened to not play against the Dodgers and Jackie Robinson in 1947 traded for First Baseman Tom Alston of the Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres. Alston would only play in 91 Major League games with his career hindered by bouts with depression and anxiety.

Nino Escalara (above) and Chuck Harmon

The Cincinnati Reds brought up Puerto Rican born First Baseman Nino Escalera and Third Baseman Chuck Harmon. Harmon had played in the Negro Leagues and had been a Professional Basketball player in the American Basketball League. Harmon who was almost 30 when called up played just 4 years in the Majors. Both he and Escalera would go on to be Major League scouts. Escalera is considered one of the best First Baseman from Puerto Rico and was elected to the Puerto Rican Baseball Hall of Fame. Harmon’s first game was recognized by the Reds in 2004 and a plaque hangs in his honor.

The Washington Senators called up Cuban born Center Fielder Carlos Paula from their Charlotte Hornets’ farm team in September 1954. Paula played through the 1956 season with the Senators and his contract was sold to the Sacramento Salons of the Pacific Coast League. He hit .271 in 157 plate appearances with 9 home runs and 60 RBIs. He died at the age of 55 in Miami.

Elston Howard

In April 1955 the New York Yankees finally integrated 8 years after the Dodgers and 6 years after the Giants. They signed Catcher/Left Fielder Elston Howard from their International League affiliate where he had been the League MVP in 1954. Howard would play 13 years in the Majors with the Yankees and later the Red Sox retiring in 1968. He would be a 12-time All Star and 6-time World Series Champion as a player and later as a coach for the Yankees. He died of heart disease in 1980. His number #32 was retired by the Yankees in 1984.

The Philadelphia Phillies purchased the contract of Shortstop John Kennedy from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League at the end of the 1956 season. Kennedy played in just 5 games in April and May of 1957.

Ozzie Virgil Sr.

In 1958 the Detroit Tigers obtained Dominican born Utility Player Ozzie Virgil Sr. who had played with the Giants in 1955 and 1956. Virgil would play 9 seasons in the Majors with the Giants, Tigers, Athletics and Pirates and retire from the Giants in 1969. He later coached for 19 years in the Majors with the Giants, Expos, Padres and Mariners.

The last team to integrate was the Boston Red Sox who signed Infielder Pumpsie Green. Green made his debut on 21 July 1959 during his three years with the Red Sox was primarily used as a pinch runner. He played his final season with the New York Mets in 1963. He was honored by the Red Sox in 2009 on the 50th anniversary of breaking the Red Sox color barrier.

It took 12 years for all the teams of the Major Leagues to integrate, part of the long struggle of African Americans to achieve equality not just in baseball but in all areas of public life. These men, few in number paved the way for African Americans in baseball and were part of the inspiration of the Civil Rights Movement itself. They should be remembered by baseball fans, and all Americans everywhere for their sacrifices and sheer determination to overcome the obstacles and hatreds that they faced. It would not be until August of 1963 that Martin Luther King Jr. would give his I Have a Dream speech and 1964 that African Americans received equal voting rights.

Spring training for the 2015 season is about to begin in Florida and Arizona, in what are called the Grapefruit and Cactus Leagues. It is hard to believe that only 68 years ago that only one team and one owner dared to break the color barrier that was, then, and often today is still a part of American life.

However in those 68 years despite opposition and lingering prejudice African Americans in baseball led the way in the Civil Rights Movement and are in large part responsible for many of the breakthroughs in race relations and the advancement of not only African Americans, but so many others.

We can thank men like Charles Thomas, Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey for this and pray that we who remain, Black and White, Asian, and Latin American, as well as all others who make up our great nation will never relinquish the gains that have been won at such a great cost.

President Obama throwing out the First Pitch for the Washington Nationals

Today we have a Black President who has the same kind of racial epitaphs thrown at him every day by whites who as they did to Charles Thomas, Jackie Robinson and so many other pioneers, Frankly such behavior can only be called what is it, unrepentant, unabashed, and evil racism. The fact is that such people don’t think that any Black man should hold such high an office, just as they did not think that Blacks should be allowed to play integrated baseball. It is anathema to them, and that is why their unabashed hatred for Obama runs so deep. They may disagree with his policies, but I guarantee if Obama was white, their opposition to him would be far more civil and respectful. But because he is half-black, and has a funny name they hate him with a passion, a passion that scares me, because words and hateful beliefs can easily become actions.

Racism still exists, but one day thanks to the efforts of the early ball-players as well as pioneers like President Obama, and the undying commitment of decent Americans to accept people regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, or even sexual orientation, we will see a new birth of freedom.

Peace

Padre Steve+

Share this:

Leave a comment

Filed under Baseball, civil rights, History, political commentary

Tagged as 1964 civil rights act, Baseball, bob trice, boston braves, boston red sox, branch rickey, brooklyn dodgers, carlos paula, charles thomas, chicago cubs, chicago white sox, chuck harmon, cincinnati reds, civil rights, cleveland indians, curt roberts, elston howard, equal rights, ernie banks, hank thompson, harry truman, i have a dream speech, integration of baseball, jackie robinson, jim crow laws, john kennedy baseball player, larry doby, martin luther king jr, minnie minoso, monte irvin, new york giants, new york yankees, nino escalera, ossie davis, ozzie virgil sr, pee wee reese, philadelphia athletics, pittsburgh pirates, president barak obama, pumpsie green, racism, roy campanela, samuel jethroe, satchel paige, spring training, st louis cardinals, st. Louis browns, tom alston, voting rights act of 1964, washington senators, willie mays