Friends of Padre Steve’s World

As I have been working to revise my materials form my next Gettysburg Staff Ride I did some revisions to my text that I use with my students. The footnotes did not show up so Monday I will repost the text of this article with them. The article is important even for non-military types who care about the country and are involved in politics or policy, because it shows the linkage between the advantages that a nation with a strong strong and effective central government has over one which adopts what we would call today a Libertarian form of government. In fact I would call the effort of the Confederacy in the Civil War “The Failed Libertarian War.” But that is possibly a subject for an article or maybe even a book, but I digress…

So anyway here is the latest,

Peace

Padre Steve+

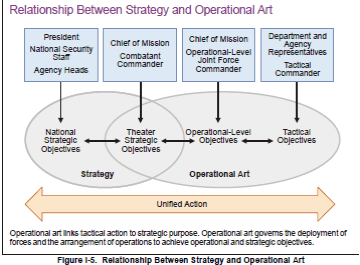

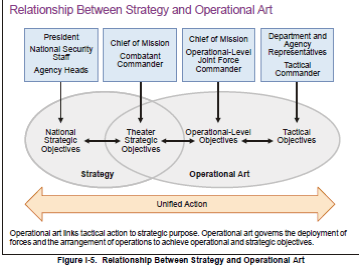

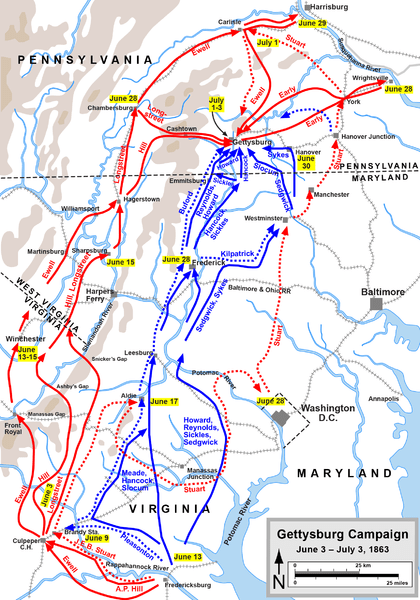

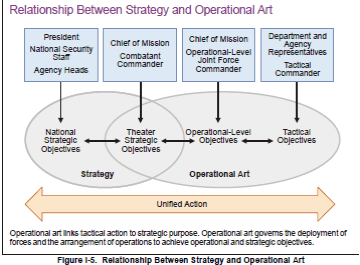

Today we look at the Gettysburg Campaign in terms of how we understand the connection between strategy and operational art. In doing so we have to place it in the context that Lee’s campaign has in relationship to the Confederate command relationships and where it fits in the continuum of unified action as we understand it today.

To do so we have to make the connection between national strategic objectives, theater objectives, operational objective and tactical objectives. We have to explore command and control structures, staff organization and the understand the effect of the Diplomatic, Informational, Economic and Military elements of national power that impact a nation’s ability to wage war.

The summer campaign of 1863 in the Civil War gives us the opportunity to do this as we explore the Gettysburg campaign in relation to Vicksburg and the overall strategic situation that both sides faced. This includes the elements that we now associate with the DIME.

While Confederate army units and their commanders generally excelled on the tactical level, and their soldiers endured hardship well, this would not be enough to secure victory. They displayed amazing individual initiative on the battlefield and they won many victories against superior forces, especially in the early part of the war. Even during the final year of the war, Lee’s forces fought skillfully and helped prolong the war. But neither the Confederate government nor the various army commanders were able to translate battlefield success to operational, theater specific or national strategic objectives.

The Confederacy had a twofold problem in its organization for war and how it conducted the war. First it had no organization at the strategic level to direct the war, and it never developed one to coordinate its military, military, diplomatic or economic policies. While Southern strategists understood that they needed to “wear down the ability of the North to wage war” they were consistently hobbled by its own internal political divisions which served to undermine efforts to coordinate the effort to defend the Confederacy. These divisions focused on the opposition of the states’ rights proponents to the central government in Richmond.

The overarching national strategic objective of the Confederacy was to attain independence. The Confederates could not hope to conquer the Union and because of that their “strategic problem was to resist conquest” and to do so they would have to “tire the Federals out, and force them to abandon the war.” Jefferson Davis seems to have understood this early in the war, but political considerations and the temperament of most Southerners and their political leaders frustrated his attempts. Generals like Lee and Joseph E. Johnston “were of the opinion that the more remote frontiers should be abandoned, and that the scattered forces of the Confederacy be concentrated, political reasons overruled their judgment.”

Southern politicians, especially the governors and congressmen demanded that troops “defend every portion of the Confederacy from penetration by “Lincoln’s abolition hordes.” Likewise, most Southerners believed that they “could whip any number of Yankees” and as early as 1861 the Confederate press was advocating an offensive strategy as the Richmond Examiner declared “The idea of waiting for blows rather than inflicting them, is altogether unsuited to the genius of our people….The aggressive policy is the truly defensive one. A column pushed forward into Ohio or Pennsylvania is worth more to us, as a defensive measure, than a whole tier of seacoast batteries from Norfolk to the Rio Grande.”

This combination of wanting to defend everything, which defied Frederick the Great’s classic dictum that “he who defends everything defends nothing” and the persistent employment of the offensive even when it “drained the Confederacy’s manpower and weakened its long term prospects for independence” were key strategic factors in its defeat.

The South did get an earlier start to in mobilizing for war then the Union. Even before the “Confederate Congress authorized an army of 100,000 volunteers for twelve months” on March 6th 1861 the governors of the eleven Confederate States raised units to fight any Federal armies which dared to force them back into the Union. This involved dusting off the old militias which had been allowed to decay in the period between the Mexican War and 1860. Most of these units in the South as well as the North were volunteer companies in which the discipline, equipment and training varied to a significant degree. Most had little in the way of real military training and “many of them spent more time drinking than drilling.” The early Confederate mobilization outstripped the availability of arms and equipment forcing many volunteers to be sent home.

Other than the stated desire for independence and their common hatred of the “Yankee,” there was little in the way of unity within the Confederate States, “the incurable jealousy of the States, especially those not immediately affected by the war, established a dry rot within the Confederacy.” Within the Confederacy, each state viewed itself as an independent nation only loosely bound to the other states and some legislatures enacted laws which actively opposed the central government in Richmond.

The various Confederate states controlled the use of their units and often resisted any effort at centralization of effort. Some kept their best units at home, while others dispatched units to Confederate armies such as Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Initially most states limited enlistment periods to one year despite the opposition of Robert E. Lee who helped Jefferson Davis pass the Conscription Act of 1862, a measure that was “heavily watered down by those politicians whose first concern was states’ rights and by those who felt that it would undermine patriotism.” That measure, even in its watered down form was distinctly unpopular, especially with the following declaration of martial law in parts of the Confederacy.

Both measures were brought by realists who understood that for the Confederacy to survive the war effort had to become a total war, with “the whole population and the whole production…put on a war footing.” Such measures provoke more attacks and opposition by their opponents who advocated states’ rights even if it worked against the overall interests of the Confederacy. By the time of Gettysburg if not sooner, “Confederate society began to unravel. The yeomanry and poor white people resented conscription, the tax-in-kind impressment, and other governmental measures than the wealthy. Planters sought to safeguard their property and status to the detriment of national goals.”

This included how state governments responded to the military needs of the Confederacy. Some governors hoarded weapons seized from Federal armories, “retaining these weapons to arm regiments that they kept at home… defend state boarders and guard against potential slave uprisings.” When in response to threats within the Confederacy Jefferson Davis suspended the writ of habeas corpus it resulted in a firestorm of opposition from the states. “Mississippi and Georgia passed flaming resolutions against the act; Louisiana presently did so, too, and North Carolina soon had a law on its books nullifying the action of the central government.” Alexander Stephens, the Confederate Vice President noted that there was “no such thing as a citizen of the United States, but the citizen of a State, and that “the object of quitting the Union, was not to destroy, but to save the principles of the Constitution.”

Likewise as economic conditions worsened and inflation soared in late 1861 the Confederate Congress “in its allotments to the War Department refused to face up to the costs of running the war…it forced the department to scramble in an atmosphere of uncertainty for allotments on a short-run basis.” There was much distrust of any attempt to organize a true central government with any actual authority or power in Richmond. Jefferson Davis may have been President but his country was hamstrung by its own internal divisions, including the often vocal opposition of Stephens for whom states’ rights remained a paramount issue. Stephens, in a statement that defied the understanding that military victory had to be achieved for independence to be won said during the habeas corpus debate “Away with the idea of getting independence first, and looking to liberty afterward.” This, like so many other aspects of the Confederate war effort showed the radical disconnection between legislators, policy makers and the Army and defied any understanding of the importance of government and the unity of effort in pursuing war aims. .

The Confederacy lacked a clear defined command structure to coordinate its war efforts. At the beginning of the war this was true of the Union as well, however, by the Union was much more adept at responding to the needs of the war, this included its military operations, diplomatic efforts and economy. Out of necessity it established a War Department as well as a Department of the Navy in February 1861 and Jefferson Davis, the new President who had served in Mexico and as Secretary of War prior to secession “helped speed southern mobilization in 1861.” However helpful this was initially Davis, who micromanaged Confederate war efforts “eventually led to conflict with some army officers.”

Jefferson Davis was an able man to be sure, but he “totally misunderstood the nature of the war.” Davis was a man given to suspicion and had major personality conflicts with all of his senior commanders save Robert E. Lee. These included Joseph Johnston who he loathed and P.T.G. Beauregard, both of whom he quarreled with on matters of strategy. These conflicts did impact operations, just as did the refusal of various states to support operations or campaigns apart from ones that impacted their state directly.

While Jefferson Davis and his Secretary of War theoretically exercised direction of the war no formal mechanism existed to coordinate the needs of the various military departments or armies. In 1863 Davis, Lee and the Secretary of War, James Seddon were acting as an “informal board which had a say in all major questions of Confederate strategy. Seddon, who had definite ideas of his own about military affairs, was usually but not always a party to Davis’ discussions with Lee…but Davis usually dominated them…. In contrast to the Northern command organization, the South had no general in chief. If anyone fulfilled his functions, it was the President.” It was not until February of 1865 that Lee was named as General in Chief of all armies, and by then the war had been lost.

While Jefferson Davis and his Secretary of War theoretically exercised direction of the war no formal mechanism existed to coordinate the needs of the various military departments or armies. In 1863 Davis, Lee and the Secretary of War, James Seddon were acting as an “informal board which had a say in all major questions of Confederate strategy. Seddon, who had definite ideas of his own about military affairs, was usually but not always a party to Davis’ discussions with Lee…but Davis usually dominated them…. In contrast to the Northern command organization, the South had no general in chief. If anyone fulfilled his functions, it was the President.” It was not until February of 1865 that Lee was named as General in Chief of all armies, and by then the war had been lost.

In effect each Confederate army and military department operated independently, often competing with each other for the troops, supplies and materials needed to fight. They also had to contend with recalcitrant state governments, each loathe to sacrifice anything that might compromise their own independence. Attempts by the authorities in Richmond to centralize some measure of authority were met with resistance by the states. Thus states’ rights were “not only the cause of the war, but also the cause of the Confederate downfall.”

In a country as vast as the Confederacy that lacked the industry, transportation infrastructure, population and economic power of the North this was a hindrance that could not be overcome by the soldierly abilities of its armies alone. An example of the Confederate problem was that “neither the army nor the government exercised any control of the railroads.” The Confederate Subsistence Department, which in theory was responsible for ensuring the supply of food, stores and the logistical needs necessary to maintain armies in the field could not plan with confidence. “Tied to the railroads, unable to build up a reserve; frequently uncertain whether or not their troops were going to be fed from one day to the next, field commanders understandably experienced a general loss of confidence in the Subsistence Department….” Even though the subsistence and even the survival of the army was dependent on the use of railroads, the railroad owners “responded by an assertion of their individual rights. They failed to cooperate….and Government shipments were accorded low priority. In May of 1863 the Confederate Congress finally granted the government broad authority over the railroads, but “Davis hesitated to wield the power. “ It would not be until early 1865 that the Confederacy would “finally take control of the railroads.”

All of these factors had a direct effect on the campaign of 1863. In the west, Confederate commanders were very much left to fend for themselves and to add to their misery failed even to coordinate their activities to meet the threat of Grant and his naval commander, Admiral David Dixon Porter. In the East, Lee having established a close relationship with Jefferson Davis as his military advisor during the first year of the war exercised a disproportionate influence on the overall strategy of the Confederacy because of his relationship with Davis. However, Lee was hesitant to use his influence to supply his army, even when it was suffering. Even though he willingly shared in the plight of his solders, Lee refused “to exert his authority to obtain supplies….” As the army prepared to invade Pennsylvania, “the paltry rationing imposed by Richmond was made worse by a tenuous supply line….”

Lee in theory was simply one of a number of army or department commanders, yet he was responsible for the decision to invade the Union in June of 1863. This decision impacted the entire war effort. The Confederate cabinet “could reject Lee’s proposal as readily as that of any other department commander, Bragg, or Pemberton or Beauregard, for example, each of whom was zealous to protect the interests of the region for which he was responsible…” But this was Lee, “the first soldier of the Confederacy- the first soldier of the world…” Lee’s plan was approved by the cabinet by a vote of five to one. The lone dissenter was Postmaster General John H. Reagan who “believed a fatal mistake had been made…”

Lee in theory was simply one of a number of army or department commanders, yet he was responsible for the decision to invade the Union in June of 1863. This decision impacted the entire war effort. The Confederate cabinet “could reject Lee’s proposal as readily as that of any other department commander, Bragg, or Pemberton or Beauregard, for example, each of whom was zealous to protect the interests of the region for which he was responsible…” But this was Lee, “the first soldier of the Confederacy- the first soldier of the world…” Lee’s plan was approved by the cabinet by a vote of five to one. The lone dissenter was Postmaster General John H. Reagan who “believed a fatal mistake had been made…”

Seddon desired to turn the tide at Vicksburg and proposed sending Longstreet’s Corps to reinforce Johnston to relieve the embattled city and maintain the front on the Mississippi. However, Lee believed that any attempt “to turn the Tide at Vicksburg…put Lee’s army in Virginia at unacceptable risk.”

The lack of any sense of unity in the Confederate hierarchy and lack of a grand strategy was disastrous. The lack of agreement on a grand strategy and the inability of the Confederate States Government and the various state governments to cooperate at any level culminated in the summer of 1863 with the loss of Vicksburg and the failure of Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania. The Confederate failure in this demonstrates the absolute need for unity of effort and even more a whole of government and whole of nation approach to war.

This can be contrasted with the Union, which though it was slow to understand the nature of the war did have people who, through trial and error developed a cohesive strategy that led to success at the operational level and the tactical level. The genus in Union strategy came from Lieutenant General Winfield Scott who “appreciated the relationship between economic factors and attack.” Scott’s strategic plan was to establish a blockade and form two major armies, “one to move down the Mississippi and cut off the western half of the Confederacy from its eastern half, while the other threatened Richmond and pinned down the main Confederate forces in Virginia.” It was a plan for total war called Anaconda which was mocked in both the Northern and Southern press and it would become the blueprint of Federal success at the war progressed. Scott was the first to recognize that the war would not be short and his plan was the first to “recognize the North’s tremendous advantage in numbers and material, and it was the first to emphasize the importance of the Mississippi Valley in an over-all view of the war.”

Abraham Lincoln had little in the way of military acumen and frequently, until Grant took control of the armies interfered with his senior commanders, often with good reason. However, Lincoln was committed to winning the war and willing to take whatever steps necessary to do so. Fuller describes him as “none other than a dictator” by bypassing Congress and on his own authority declaring a blockade of Southern ports, calling for 75,000 volunteers and suspending habeas corpus.

Likewise Lincoln as well as Congress understood the value and necessity of the railroads and in January 1862 “Congress authorized to take possession of any railroads and place them under military control when the public safety warranted it.” Lincoln formed the Department of Military Railroads the following month and appointed Daniel C McCallum as its director. In May President Lincoln formally took possession of all railroads, but “saw to it that cooperative lines received government aid.”

George McClellan, who Lincoln appointed as commander of the Army of the Potomac in 1862, whatever his many faults as a field commander “possessed a strategic design for winning the war,” understood the necessity of unity of command and successfully built an effective army. Now his design was different than that of Scott, for he desired to “crush the rebels in one campaign” by an overland march to Richmond. While this was unrealistic because of McClellan’s constant overestimation of his enemy and inability to risk a fight when on the Peninsula and at the gates of Richmond, the Union might have at least had a chance should he have defeated the major Confederate forces deployed to defend that city. While that would have been unlikely to win the war in a single stroke it would have been a significant reversal for the Confederacy in 1862.

Logistics was one of the deciding factors of e war, both the Confederate weakness and Union ability to adapt society and government needs to wartime conditions. As a general principle Union leaders, government and business alike understood the changing nature of modern war. This stood in stark contrast to the inefficient and graft ridden Confederate agencies where even those who wanted more effective means to wage war were hindered by politicians, land owners and businessmen who insisted on their rights over the needs of the nation. The Union developed an efficient and well managed War Department where the importance of logistics inter-bureau cooperation became a paramount concern.

Union industry “geared up up for war production on a scale that would make the Union army the best fed, most lavishly supplied army that have ever existed.” The Quartermaster’s Department under the direction of Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs was particularly efficient in supplying the needs of a military fighting on exterior lines in multiple theaters of operation. Unlike the Confederate Subsistence Bureau the Federal Quartermaster Bureau supplied almost everything the army could need: “uniforms, overcoats shoes, knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, mess gear, blankets, tents, camp equipage, barracks, horses, mules, forage, harnesses, horseshoes, and portable blacksmith shops, supply wagons, ships when the army could be supplied by water, coal and wood to fuel them, and supply depots for storage and distribution.” The ill-equipped Confederates could only look on with awe, in fact during his absence from Lee J.E.B. Stuart was ecstatic over the capture of “one hundred and twenty five of the best United States model wagons and splendid teams….” likewise one of the reasons that A.P. Hill allowed Harry Heth to send his division the Gettysburg was to find shoes that the Confederate Subsistence Department could not provide for them. Thus one of the reasons for the Battle of Gettysburg is directly linked to the failed logistics system of the Confederacy.

Early in the war the Union logistics effort was beset by some of the same problems that plagued the Confederacy throughout the war. Graft and corruption ran rife until 1862 when “Congress established investigative committees to uncover fraud and passed laws regulating the letting of contracts.” Meigs overhauled the bureau. At the beginning of the war it had only one department, for clothing. He modernized this and added eight new departments, which dealt with “specialized logistical functions such as forage and fuel, barracks and hospitals and wagon transportation.” During the war Meigs managed nearly half the direct costs of the Union war effort,” over 1.5 billion dollars in spending. He has been called by James McPherson as “the unsung hero of northern victory.”

The Unsung Union Hero: General Montgomery Meigs

This had a profound effect on operations. When the Union forces by necessity had to operate in enemy territory they were well supplied whereas whenever Confederate Forces conducted operations in the North or even in supposedly friendly Border States they were forced to subsist off the land. This meant that Confederate operations in the north were no more than what we would call raids, even the large invasions launched by Lee in 1862 and 1863, both which ended in defeat and near disaster.

Because of their poor logistic capabilities Confederate forces had no staying power to keep and hold any ground that they took in enemy territory. This can be contrasted with the Union which when it sent its forces south meant them to stay.

Lee could not fathom this and because he believed that no Federal Army could stand a summer in the Deep South and that Grant would be forced to withdraw. The use of railroads to supply its far flung forces operating in the south as well as its use of maritime transportation along the coast and on inland waterways ensured that Northern armies could always be supplied or if threatened could be withdrawn by ship.

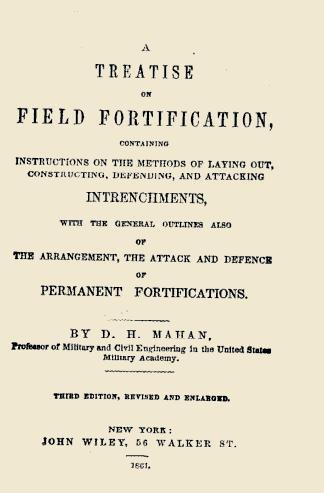

Some senior Union officers also understood the importance of logistics. Henry Halleck was the first true American military theorist. He published the first American work on strategy, Elements of Military Art and Science in 1846. While his is often given short shrift because he was not an effective field commander and had an acerbic personality which rubbed people the wrong way, Halleck was one of the most important individuals in organizing the eventual Union victory. This included matters of strategy, picking effective subordinate commanders and understanding the logistical foundations of strategy.

Weigley wrote of Halleck:

“He sponsored and encouraged the operations of Brigadier General Ulysses. S. Grant and Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote that captured Forts Henry and Donaldson in February 1862 and thereby opened up the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers for Union penetration deep into the state of Tennessee and toward the strategically important Memphis and Charleston Railroad. Halleck’s insights into the logistical foundations of strategy proved consistently accurate. Throughout the war, he maintained a shrewd eye for logistically viable lines of operation for the Union forces, and he increasingly recognized that one of the most effective weapons of offensive strategy, in an age when battle meant exposure to rifled firepower, was not to aim directly at the enemy armies but at their logistical base.”

Halleck was also instrumental in helping to oust Hooker just before Gettysburg and raise Meade to command the Army of the Potomac. When Lincoln brought Grant east to become General in Chief Halleck took on the new position of Chief of Staff. This was a task that he fulfilled admirably, allowing Grant to remain in the field and ensuring clear communication between Lincoln and Grant as well as relieving “Grant of the burden of personally corresponding with his department commanders.”

By establishing what we now understand as the beginning of a modern command and staff organizational structure the Union was far more able to link its national, theater and operational level objectives with its tactical objectives, even when some of its commanders were not as good as Confederates and blundered into defeats. Above the army, at the administration level Stanton, the Federal Secretary of war organized a War Board and “composed of department heads and chaired by Major General Ethan Allen Hitchcock…as an embryonic American-style general staff.”

In the end during the summer of 1863 it was the Union which was better able to link the ends, ways and means of the strategic direction of the war. This is something that Davis and Lee were unable to do as they struggled with political division, a lack of cooperation from the states, and the lack of any true grand strategy.

Lee’s strategy of the offensive was wrong and compounded the problems faced by the Confederacy. The losses that his army suffered were irreplaceable, not just in terms of overall numbers of soldiers but in terms of his mid-level leaders, his battalion, regiment and brigade commanders who suffered grievous losses and were even more critical to the leadership of his army.

Lee recognized the terrible effects of his officer casualties in a letter to General John Bell Hood on May 21st: “There never were such men in an Army before. But there is the difficulty- proper commanders- where can they be obtained?” His actions at Gettysburg only added to his crisis in keeping his army supplied with competent commanders, as so many were left dead, wounded or captured during the campaign.

Even had Lee won the battle of Gettysburg his casualties in Union territory would have been prohibitive. He would have spent most of his ammunition, incurred serious losses in personnel and horses, and been burdened by not having to care for his wounded and still been deep in Union territory away from his nearest logistics hub. Had Lee won at Gettysburg “his ammunition would have been nearly exhausted in victory, while Federal logistics would have improved as the Army of the Potomac fell back toward the eastern cities.” This would have forced him to withdraw from Pennsylvania even had he been victorious.

It is true that a victory on northern soil might have emboldened the peace party in the North, but even then that could not have an effect on the desired effect on the Lincoln Administration until the election of 1864, still 16 months away. Likewise, in July 1863 such a victory would probably not have triggered foreign recognition or assistance on the part of France or England. “Skilful northern diplomacy prevented an internal conflict from becoming an international war.” Jefferson Davis held on to his fantasy until August 1863, when even he was forced to deal with reality was a vain hope indeed and ended his diplomatic efforts to bring England into the war.

England would not intervene for many reasons and the Confederate government did not fully appreciate the situation of the countries that they hoped would intervene on their behalf:

“its dependence on northern foodstuffs, access to new cotton supplies, turmoil in Europe, fear of what might happen to Canada and to British commerce in a war with the Union, and an unwillingness to side with slavery. The British government also wanted to establish precedents by respecting the blockade, a weapon that it often used.”

Confederate politicians were hindered by a very narrow, parochial view of the world, had little understanding of modern industry, economics and the type of diplomacy employed by Europeans both to strengthen their nations, but also to maintain a balance of power.

As we look at the Gettysburg and Vicksburg campaigns in the summer of 1863 these are important things to consider. The relationship between national strategic objectives, theater objectives, operational objectives and tactical success cannot be minimized. Success on the battlefield alone is almost always insufficient to win a war unless those wins serve a higher operational and strategic purpose, and the costs of battles and campaigns have to be weighed in relation to the strategic benefits that derive from them.

In the end the total failure of the two campaigns destroyed any real hope of Confederate military victory. At Vicksburg the Confederacy lost all of Pemberton’s army, 33,000 men and Lee suffered over 28,000 casualties from an army which had begun the campaign with about 80,000 troops. The losses were irreplaceable.

This essay is certainly not an exhaustive look at the subject, but if we do not consider these factors we cannot really understand the bigger picture of the situation that the two sides faced and how they dealt with them. While the weapons and tactics employed by the sides are obsolete the thought processes and strategic considerations are timeless.

Ewell’s Corps crossing the Potomac

Ewell’s Corps crossing the Potomac Lieutenant General Richard Ewell

Lieutenant General Richard Ewell Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker

Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker At Upperville Pleasanton’s troopers “pressed Stuart’s cavalry so hard that Lee ordered McLaws’ division of Longstreet’s Corps to hold Ashby’s Gap, and he momentarily halted Major General Richard Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps on its way to Shepherdstown.” (27) Stuart’s men were successful in protecting the gaps and ensuring that the Federal troopers did not penetrate them, but “Pleasanton learned, however, from prisoners and local citizens, “The main body of the rebel infantry is in the Shenandoah Valley.” (28)

At Upperville Pleasanton’s troopers “pressed Stuart’s cavalry so hard that Lee ordered McLaws’ division of Longstreet’s Corps to hold Ashby’s Gap, and he momentarily halted Major General Richard Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps on its way to Shepherdstown.” (27) Stuart’s men were successful in protecting the gaps and ensuring that the Federal troopers did not penetrate them, but “Pleasanton learned, however, from prisoners and local citizens, “The main body of the rebel infantry is in the Shenandoah Valley.” (28)