Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

I’ve been working of trying to finish my manuscript for my book “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory” much of the night and have pretty much absented myself from social media. However, had a nice night with Judy and playing with our pups. Our Youngest Maddy Lyn, is so full of herself and full of energy that she gives all of us a run for our money. Anyway, this is another segment of one of my Gettysburg book manuscripts dealing with the reorganization of Lee’s Army after Chancellorsville in preparation for Lee’s invasion of the north, which culminated at Gettysburg. Today is a look at the leaders of Major General J.E.B Stuart’s Cavalry Division as well as three other generals, Brigadier General John Imboden who commanded an independent cavalry brigade, Lee’s Chief of Artillery, Brigadier General William Pendleton, Whose artillery had been reorganized leaving him with few actual duties, and Major General Isaac Trimble. This like the previous sections of this chapter of my Gettysburg text is interesting because it shows the complexities of the lives and personalities of the men leading these units. Professional soldiers, volunteers with little military experience, soldiers, lawyers, engineers and politicians they are an interesting collection of personalities; some surrounded in myth and others practically unknown. I think it is important for anyone studying a war, a campaign, or a battle to at least look at the lives of the men who planned and fought it. In doing so, even those that oppose what they did in rebelling against the United States can find in them some measure of humanity, and sometimes even gain a sense of empathy for some of them.

That is why when we look at the lives of soldiers, we have to take the time to at least try to understand the nuance, the contradictions, their strengths and weaknesses as leaders, as well as a measure of their character.

Have a great night, and pray that I can finish “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory” tomorrow.

Peace

Padre Steve+

Stuart’s Cavalry Division

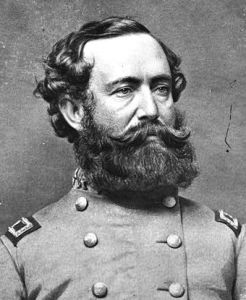

Major General J.E.B. Stuart C.S.A.

The Cavalry Division was commanded by Major General J.E.B. Stuart. While it was considered a division, Stuart’s command was the size of a Union Army Corps with over 10,000 troopers assigned. Despite its large size at Gettysburg the Division was split by agreement of Lee and Stuart. Stuart who had five brigades at his immediate disposal would take three of them, Hampton’s, Rooney Lee’s and Fitz Lee’s on an ill-fated mission which would leave him and them out of the fight during the most important part of the movement to and first two days of battle. His raid causes him “to be absent on the day of all days when he could reconnoiter the Federal position.” [1] Two, Robertson and Grumble Jones’s would remain guarding passes along the Blue Ridge long after that mission had any relevance. Imboden’s would be far to the west and Jenkin’s ere with Ewell’s vanguard in the advance north.

Major General James Ewell Brown Stuart was the son of a former congressman whose family went back five generations in Virginia. He graduated thirteenth in a class of forty-six at West Point in 1854. Classmates included Dorsey Pender and Oliver O. Howard. A fellow cadet who would serve under Stuart during the war, Fitzhugh Lee wrote:

“His distinguishing characteristics were a strict attention to his military duties, an erect, soldierly bearing, an immediate and almost thankful acceptance of a challenge from any cadet to fight, who might in any way feel himself aggrieved, and a clear, metallic, ringing voice.” [2]

At West Point Stuart was noted for his “lifelong religious devoutness. When he was at West Point he was known as a “Bible Class Man.” [3] Stuart was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant and assigned to the Mounted Rifles, which Stuart noted was “a corps which my taste, fondness for riding, and my desire to serve my country in some acceptable manner led me to select above all the rest.” [4]Stuart would serve with the Mounted Rifles for about a year before being selected to serve in one of the first Cavalry regiments formed, the First Cavalry at Jefferson Barracks Missouri.

In the pre-war years the young officer developed a solid reputation in the army where he served on the frontier and in “Bleeding Kansas.” In those years Stuart “was already a young officer of great promise, a natural horseman with a reputation for dash and bravery gained in countless clashes with Indians throughout the West, and for steady competence in the pro- and antislavery warfare of Kansas.” [5]

In 1859 Stuart was on leave visiting Washington D.C. and staying with the Lee’s at Arlington. He was visiting the War Department when news came of John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry. He was given a letter to take to Lee which ordered Lee to take command of troops to suppress the rebellion. Stuart accompanied Lee on the mission and was send by Lee to present terms of surrender to the raiders, who at the time were still nameless to the Federal authorities. Stuart entered the building and was confronted by Brown who he had previously met in Kansas. After some fruitless negotiation, Stuart realized that Brown was not about to surrender. At some time Stuart broke away and motioned for the Marines to move in. “Three minutes after Stuart had given his signal, the affair was over.” [6]

Stuart resigned his commission when Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861, while his father-in-law, Colonel Philip St. George Cooke remained in Union service. He commanded the 1st Virginia Cavalry in the Valley and at First Manassas and was promoted to Brigadier General in September 1861. The following month he was given command of the army’s cavalry brigade and distinguished himself in the eyes of both General Joseph Johnston and Robert E. Lee. Johnston wrote to President Jefferson Davis praising the young brigadier “He is a rare man…wonderfully endowed by nature with the qualities necessary for an officer of light cavalry….If you add to this army a real brigade of cavalry, you can find no better brigadier-general to command it.” [7]

Lee came to share that opinion and over the course of his service Stuart had come to:

“demonstrate a real talent for the most mundane and most essential role cavalry played in this war – reconnaissance and intelligence gathering. No intelligence source surpassed his eye for seeing and evaluating a military landscape or an enemy’s strengths and dispositions.” [8]

This would be something that Lee came to rely and which he would dearly miss at Gettysburg.

Despite his excellence in this “most mundane” task Stuart developed a flair and passion for the spectacular, which was first demonstrated during the Seven Days, where he took his cavalry on a circuit of McClellan’s army which not only gathered a significant amount of intelligence also unnerved the Army of the Potomac. His raid was “flawlessly executed….” And Stuart “became a hero to his troopers and one of the idols of the public.” [9] Lee wrote that Stuart’s operation “was executed with great address and daring by accomplished officer.” [10] The raid did have its detractors, especially among the infantry and it also revealed something to Stuart that appealed to his own vanity, “that raiding would easily garner headlines in the Richmond papers.” [11]

Stuart Lee’s staff secretary, Colonel Robert Taylor noted that Stuart was “possessing of great powers of endurance, courageous to an exalted degree, of sanguine temperament, prompt to act, always ready for fight – he was the ideal cavalryman.” [12] Stuart also kept a lively headquarters. Taylor remarked “How genial he was! There was no room for “the blues” around his headquarters; the hesitating and desponding found no congenial atmosphere at his camp; good will, jollity, and even hilarity, reigned there.” [13]

Stuart always had his African-American banjo player with him and frequently sang around camp and on campaign. That was not always appreciated by some other officers. Wade Hampton, who in time became Stuart’s right-hand man was not impressed with the atmosphere at Stuart’s headquarters and “was not certain that he could flourish, or even survive, among such people….” [14] Lafayette McLaws wrote home complaining not only about Stuart but others:

“Stuart carries around with him a banjo player and special correspondent. This claptrap is noticed and lauded as a peculiarity of genius, when, in fact, it is nothing more but the act of a buffoon to get attention.” [15]

But Stuart was always aware of his own mortality and there was a serious side to him, often expressed in his faith, which impressed those around him. His West Point classmate and friend, Oliver O. Howard wrote:

“J.E.B. Stuart was cut out for a cavalry leader. In perfect health, but thirty-two years of age, full of vigor and enterprise, with the usual ideas imbibed in Virginia concerning State Supremacy, Christian thought and temperate by habit, no man could ride faster, endure more hardships, make a livelier charge, or be more hearty and cheerful while so engaged. A touch of vanity, which invited the smiles and applause of the fair maidens of Virginia, but added to the zest and ardor of Stuart’s parades and achievements.” [16]

At Chancellorsville Stuart assumed acting command of Jackson’s Second Corps which he led well during the battle, even impressing the infantry, who had long derided Stuart and his cavalry. Leading by example “seemed on fire.” Stuart sang as he led the Stonewall Brigade into action and “the troops joined him, singing while they loaded and fired.” One officer stated “Jeb impressed himself on the infantry.” [17]

Some believed that Stuart should have been appointed to command Second Corps after Jackson’s death, but evidently Lee valued Stuart’s role as a cavalry commander more and despite his accomplishments refused to proffer the command to Stuart. Colonel Rosser told Stuart, who was grieving the loss of his friend Jackson “On his death bed Jackson said that you should succeed him, and command his corps.” Stuart responded “I would rather know that Jackson said that, than to have the appointment.” [18] One wonders what might have occurred during the Gettysburg campaign if Stuart had commanded Second Corps and left the cavalry to someone like the accomplished and level headed Wade Hampton.

Stuart was mortally wounded less than a year after Gettysburg at the Battle of Yellow Tavern, upon his death Hampton was promoted to command what was left of the Cavalry Corps.

Hampton

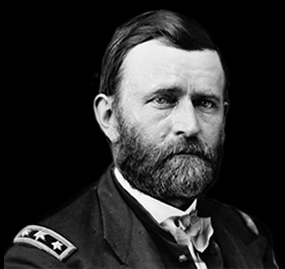

Brigadier General Wade Hampton C.S.A.

Brigadier General Wade Hampton is one of the fascinating and complex characters in either army who served at Gettysburg. He defies a one dimensional treatment or stereotype. His complexities, contradictions and character make him one of the most interesting men that I have written about during my study of this battle.

Wade Hampton III was one of the richest, if not the richest man in the Confederacy when the war broke out. He had inherited his family’s expansive plantation and many slaves and studied law at the College of South Carolina. As a slave owner he expressed an aversion for the institution, ensured that his slaves were well cared for by the standards of his day, including medical care, he never condemned slavery or worked for the abolition of a system that had made him and his family quite prosperous. He served in the South Carolina legislature and Senate, where he took an “active and prominent role in the public debate on many issues. He was vocal not only on the perils of reopening the African slave trade but also on whether and how his state should seek redress of wrongs, real and imagined, by the federal government.” [19]

As a state senator Hampton was pragmatic, and while he defended the South’s economic interests in slavery, Hampton cautioned against the rhetoric of secessionist fire-breathers. His argument was about “the preservation of the South’s political power and her social and economic institutions, now threatened by the short sighted policies of otherwise good and decent men.” [20] He did not wish to do anything that would lead to the destruction of the South, and he felt that the “only viable course was moderation, conciliation, compromise….” [21]

Hampton was a classic rich “Southern moderate He had opposed secession, and the fire eaters repulsed him.” [22] However, when Lincoln called for volunteers Hampton volunteered to serve in a war that he did not want, which would cost him dearly, and change him from a moderate to a vociferous opponent of most Reconstructionist policies.

Volunteering at the age of forty-three, Hampton had no prior military training. However, he had great organizational skill, leadership ability and a tremendous care and compassion for those who served under his command. Using his own money Hampton organized what would now be called a combined arms unit, the Hampton Legion, which comprised eight companies of infantry, four of cavalry and a battery of light artillery. He was careful in the appointment of the Legion’s officers choosing the best he could find.

Hampton rapidly rose to prominence as a respected officer and commander despite his lack of military training or experience. His soldiers fought well and took over command of an infantry brigade on the Peninsula, and was promoted to Brigadier General in May of 1862 and given command of a cavalry brigade serving under J.E.B. Stuart in July and he “became Stuart’s finest subordinate.” [23] As a brigade, and later division commander, Hampton had “little fondness or respect for Stuart. He regularly criticized Stuart for pampering the Virginia regiments and assigning his South Carolinians to the more arduous tasks.” [24]

During the war he was wounded several times, including at Gettysburg where he took two sabre cuts to the head. Eventually he took command of the Cavalry Corps after Stuart was killed in action. He fought in nearly every cavalry engagement under Stuart and led his own raids deep into Union territory. He fought well, but “hated the war. In October 1862 he wrote home: “My heart has grown sick of the war, & I long for peace.” [25] Hampton was “one of only three civilians to attain the rank of Lieutenant General in Confederate service.” [26]At Petersburg his son Preston was mortally wounded and died in his arms even as his other son Wade IV was wounded when coming to Preston’s aid. Douglass South Freeman wrote of Hampton:

“Untrained in arms and abhorring war, the South Carolina planter had proved himself the peer of any professional soldier commanding within the same bounds and opportunities. He may not have possessed military genius, but he had the nearest approach to it.” [27]

The war that he opposed cost him the life of his brother, one of his sons and his livelihood. “His property destroyed, many of his slaves gone, and deep in debt from which he would never recover, Hampton faced the future with $1.75 in his pocket.” [28] The war changed the former moderate into a man who sought vindication in some ways, but reconciliation with the black population.

Hampton again entered politics and became the first post-Reconstruction Governor of South Carolina when President Rutherford Hayes withdrew the Federal troops which had supported the Reconstructionist governor. During his campaign and during his terms as Governor, Hampton “opposed the South’s imposition of so-called “black codes” which so restricted the freedom of former slaves as virtually to return them to civility.” [29] Unlike many in the post-reconstruction South Hampton won the thanks of African Americans for condemning whites that would vote for him if they thought that he would “stand between him and the law, or grant him any privileges or immunities that shall not be granted to the colored man.” [30]

Hampton came to dominate South Carolina politics for fifteen years, after two terms as Governor he served as a U.S. Senator until 1891 when a political enemy won the governorship and forced him from the Senate. When he died on April 11th1902 his final words were “God bless my people, black and white.” [31]

Like so many leaders of so many tumultuous eras, Hampton was complex and cannot be easily classified. He was certainly not perfect, but in war and in peace gave of himself to his state and community.

Rooney Lee

Brigadier General William Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee C.S.A.

Brigadier General William Fitzhugh Lee, who went by his nickname “Rooney” to distinguish himself from his cousin Fitzhugh Lee, was the second son of Robert E. Lee. He was educated at Harvard and received a direct commission into the Army in 1857, which he resigned in 1859 to manage the White House planation which had been left to him by his grandfather. When war came Lee volunteered for service and was named Colonel of the 9th Virginia Cavalry earning the trust and respect of Stuart and the quiet admiration of his father.

Rooney Lee was promoted to Brigadier General in September 1862 and was wounded at the Battle of Brandy Station as the Gettysburg campaign began and while convalescing was captured by Union forces. He was replaced by Colonel John R. Chambliss, an 1853 graduate of West Point who had left the army after a short amount of active service prior to the war. He was viewed as a competent cavalry tactician and “there was no perceptible anxiety when “Rooney” Lee’s brigade came under Chambliss’ command.” [32]

He was paroled and exchanged in March of 1864. He was promoted to Major General in April 1864 and served until his surrender with the army at Appomattox. After the war he would return to farming and serve in the Virginia legislature and as a Congressman.

Robertson

Brigadier General Beverly Roberson C.S.A.

Brigadier General Beverly Roberson was a native Virginian who graduated from West Point in 1849. Most of his service was spent on the frontier with the Second Dragoons where for part of his service he served under command of J.E.B. Stuart’s father-in-law Colonel Philip St. George Cooke who “commended him repeatedly in dispatches.” [33]

Robertson was a veteran of much Indian service and “in person the embodiment of the fashionable French cavalry officer of the time.” [34] Robertson was dismissed from the U.S. Army in August 1861 when it was discovered that he had accepted an appointment in the Confederate army in April 1861.

Robertson’s Confederate service was less than distinguished. He never meshed with Jackson when he commanded Jackson’s cavalry, and Stuart was less than impressed when Robertson’s brigade was assigned to his command. During the Second Manassas campaign Stuart observed Robertson’s less than stellar performance, and his centrality to “so many cavalry quarrels” convinced Stuart that the old regular army veteran and West Pointer “must go. Within a month Robertson was transferred. He would finally go, as one of Stuart’s staff noted, “much to the joy of all concerned.” [35]

Robertson and his brigade were transferred to North Carolina, but returned to the Army of Northern Virginia to participate in the Gettysburg campaign. It was far too easy for Lee to obtain. D.H. Hill commanding in North Carolina “characterized Robertson’s command as “wonderfully inefficient,” [36] and Robertson would prove that again in the coming campaign where he would fail “miserably in his primary duty.” [37] After Gettysburg Robertson was relieved and reassigned to the Department of South Carolina where he served with little distinction until the end of the war.

Fitzhugh Lee

Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee C.S.A.

Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee was a nephew of both Robert E. Lee and Confederate Adjutant General Samuel Cooper. He “graduated forty-fifth in a class of forty-nine at West Point in 1856.” [38] He was wounded on the frontier and was an instructor at West Point when Virginia seceded. He resigned his commission and was appointed as a Captain. Through his friendship with Stuart he was promoted to Colonel and given command of the First Virginia Cavalry after Grumble Jones was reassigned to the 7th Virginia. He and Stuart “shared a frolicsome nature and hearty laughter, but Lee’s abilities as a horse soldier were limited.” [39]

Wade Hampton held Lee in low regard, and Hampton believed that that Lee was representative of the “most objectionable qualities of the Virginia aristocrat – vanity, ostentation, pomposity, and condensation.” [40] Despite a condition which includes arthritis which hampers him he “fights hard and learns much of the art of command.” [41] He serves until the end of the war, finally surrendering his command in North Carolina.

After the war Fitz Lee enters politics, is elected governor of Virginia and following his defeat in attempting to become U.S. Senator was appointed as counsel-general in Havana by President Grover Cleveland. When the United States went to war with Spain, Lee was appointed as a Major General of Volunteers and serves honorably. Wade Hampton, whose regard for Lee did not increase during the war told his son Albert, who had volunteered to serve on Lee’s staff “Under no circumstances would he have a sin of his ever serve under “such an imperious blowhard as Robert E. Lee’s nephew continued to be.” [42] Lee was retired from the United States Army in 1901 with the rank of Brigadier General and died in Washington D.C. on April 28th 1905.

“Grumble” Jones

Brigadier General William “Grumble” Jones C.S.A.

Another of the old army cavalrymen to serve under Stuart was Brigadier General William “Grumble” Jones. Jones was an 1848 graduate of West Point and served on the frontier. In 1852 he and his new bride were in a shipwreck, and she was swept out of his arms and drowned. “Jones never recovered in spirit. Embittered, complaining, suspicious he resigned from the army” [43] in 1857 and returned to Virginia.

Jones raised a company at the beginning of the war, and served under Stuart at First Manassas, and from the beginning took a dislike to his young superior. He grumbled to his men that he “would take no orders from that young whippersnapper.” [44] When Stuart was promoted he was made Colonel of the 1stVirginia Cavalry. The assignment did not go well for him. His loathing for Stuart grew and one officer wrote that it “ripened afterwards into as genuine hatred as I ever remembered to have seen.” [45] His hatred of Stuart expanded into a hatred for his Lieutenant Colonel, Fitzhugh Lee, who was a close friend of Stuart. Jones was unpopular with the regiment and Lee much admired and the situation became so bad that Jones was reassigned to command the 7th Virginia Cavalry. Jones performed well in this duty, well enough to warrant promotion and he was promoted to Brigadier General in September 1862. The promotion allowed Lee to send Jones to serve in the Shenandoah Valley away from Stuart since their relationship was so toxic and Jones’s hatred of Stuart “bordered on pathological.”[46]

The need for cavalry for the upcoming invasion of Pennsylvania forced Lee to bring Jones and his command back to the Army of Northern Virginia. Stuart expressed his misgiving to Lee but was given no choice in the matter. Since Jones “had the biggest brigade in the division and had the reputation of being the “best outpost officer” [47] Stuart solved his problem by leaving Jones with Robertson to guard the passes of the Blue Ridge.

After Gettysburg Jones clashed again with Stuart over not being recommend for promotion when the division became a corps. The affair was so explosive and Jones reportedly “cursed him venomously” [48] an offense so great that Stuart had him arrested and court-martialed. The court found him guilty, and although Lee had great respect for Jones’s abilities as a brigade commander he wrote to Jefferson Davis:

“I consider General Jones a brave and intelligent officer, but his feelings have become so opposed to General Stuart that I have lost all hope of his being useful in the cavalry here… He has been tried by court-martial for disrespect and the proceedings are now in Richmond. I understand he says he will no longer serve under Stuart and I do not think it advantageous for him to do so.” [49]

Jones was assigned to command in Southwestern Virginia where “organized a cavalry brigade and rendered excellent service.” [50] In June of 1864, his understrength command was defeated and he was killed at the Battle of Piedmont. Douglas Southall Freeman called his death “a tragic end to a tragic life.” [51]

Jenkins

General Albert G. Jenkins C.S.A.

General Albert G. Jenkins was another anomaly in the Army of Northern Virginia. He was a native of the far western county of Virginia, Cabell County which was one of the six counties to secede from Virginia after Virginia seceded from the Union. He had no previous military training and like many of the Confederate volunteer officers was a lawyer and politician before the war. At the outset of the war he raised a company of volunteer cavalry from that area, which grew to become the 8th Virginia Cavalry.

Jenkins was promoted to Brigadier General and he and three regiments of his brigade were requisitioned by Lee for the invasion of Pennsylvania. The brigade was badly needed but the troops “had not been well schooled in cavalry tactics or in hard fighting at close quarters. Some had the complex of home guards, and some preferred the life of a guerilla to that of a trooper, but many were good raw material” [52] who Lee hoped could be wielded into a good cavalry force.

Jenkins was wounded on July 2nd in an action east of Gettysburg and his brigade was commanded by a subordinate during the final cavalry clash on July 3rd 1863. Jenkins and his brigade returned to the Valley where he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain in May of 1864.

Attached or Staff Officers: Imboden, Pendleton and Trimble

Imboden

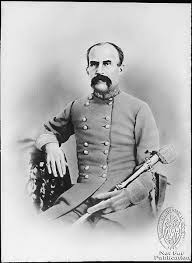

Brigadier General John Imboden C.S.A.

Brigadier General John Imboden commanded a cavalry brigade which operated independently of Stuart’s division during the campaign. Imboden had no prior military experience before the war. He was a graduate of Washington College and a lawyer in Staunton Virginia. He raised a volunteer battery of light artillery, occupied “Harpers Ferry less than thirty hours after Virginia’s secession from the Union.” [53]

Imboden fought at Manassas where he and his battery gave a respectable performance. After Manassas Imboden raised another unit, “the 1st Virginia Partisan Rangers (later called the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry)” [54] and operated primarily in the valley and western Virginia. His command expanded in size and he was promoted to Brigadier General in January 1862.

His command during the Gettysburg campaign included the 18th Virginia Cavalry, the previously mentioned 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry, a battery of artillery and several other partisan units. Imboden and his unit had been on “irregular, detached duty, and many of his men had recently been recruited, some from the infantry service.”[55] Imboden’s “brigade” was “more an assortment of armed riders even more unruly and untrained than Jenkins’ and possessing a well-developed proclivity to rob civilians, especially of their horses.” [56] However, they were useful for foraging and guarding supply bases and wagon trains during the march north. It was of dubious value in fighting “pitched battles with veteran enemy cavalry” [57] and would not be used in that capacity. Lee and Stuart did understand the limitations of such irregular formations.

Pendleton and Trimble – Generals Without Commands

During the march north Imboden’s command slipped away and when found was discovered to be “resting idly at Hancock Maryland, more than fifty miles from Chambersburg When this became known it was to provoke the wrath of Lee as did few events of the war.” [58] Imboden and his brigade served well during the army’s withdraw from Gettysburg, protecting the wounded and the trains. Overall Imboden was not well respected by Lee, Stuart or Early who he later served under and the brigade was not an effective fighting force. As such Lee sent it back to the Valley after Gettysburg.

Pendleton

Brigadier General William Pendleton C.S.A.

Brigadier General William Pendleton graduated fifth in his class at west Point in 1830, in the class behind Robert E. Lee and was commissioned as an artillery officer. He spent little time on active service and spent most of his active duty in hospitals battling the effects of “fever, nausea, and paralyzed limbs from an illness that may have been yellow fever.” [59] He resigned his commission in 1833, became a teacher and then entered the ministry as an Episcopal Priest. He pastored Grace Episcopal Church in Lexington where after John Brown’s raid he was asked to assist and train some men who had formed a battery of artillery. When war came he was elected Captain of the battery and served at First Manassas. Joseph Johnston appointed Pendleton as Chief of Artillery as he does have a certain amount of organizational skill, and “Johnston appointed him to the post more for his administrative ability, not for his tactical control of cannon on the battlefield.” [60]

When Lee took command he kept Pendleton in the position, in large part due to their friendship and spiritual connection as Episcopalians. As an artillery commander Pendleton showed his limitations during the Malvern Hill, Antietam and Chancellorsville, all of which harmed Confederate efforts on the battlefield. A junior officer remarked: “Pendleton is Lee’s weakness…. He is like the elephant, we have him and we don’t know what on earth to do with him, and it costs a devil of a sight to feed him.” [61]

His miserable performance “makes the younger men of the artillery wonder if he has the basic qualities of command.” [62]As such Lee removed him from command and returned him to his staff position and his “impatient subordinates hoped that would sever him from any combat role.” [63] At Gettysburg, Pendleton’s interference in moving the artillery trains to the rear and repositioning batteries without informing Porter Alexander, would again prove harmful to Confederate efforts.

Pendleton’s relationship with Lee, and his impact as a spiritual leader kept him with the army, today it would be argued that such a man should have been the senior chaplain of the army rather than remain in any form of combatant role. He did have a major effect on many leaders and soldiers as a source of spiritual encouragement. In fact, he “played such an invaluable role in the spiritual well-being of the army, travelling throughout the army and offering Divine Liturgy so frequently that Lee was loath to remove him as artillery chief, even when more accomplished and capable officers were available.” [64] A junior officer remarked: Pendleton was with Lee at Appomattox and after the war the two remained close, Pendleton helping to secure Lee’s appointment at Washington College and Lee serving on the vestry of Pendleton’s parish. When Lee died it was Pendleton who conducted the last rights as the family gathered around Lee’s deathbed. [65]

Trimble

Major General Isaac Trimble C.S.A.

Major General Isaac Trimble was a General without a command. One of the oldest Confederate Generals at Gettysburg, William “Extra Billy” Smith was older, Trimble graduated from West Point in 1822 and served as a lieutenant of artillery for ten years. He resigned in 1832 and spent the years before the war “as engineer for a succession of Eastern and Southern roads then being constructed.” [66] At the time of secession “Trimble was general superintendent of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, and Marylanders regarded him as one of their most distinguished citizens.” [67] He immediately went to Virginia and was appointed as a Colonel of Engineers and was rapidly promoted to Brigadier General. At First Manassas it was his skill with railroads that enabled the troops from the Valley to join with P.T.G. Beauregard’s forces, it was “an assignment that would have overtaxed the ingenuity of any railroad man.” [68] Likewise, it was the first and last time that the Confederacy would use railroads to their fullest advantage.

Trimble led a brigade of Ewell’s division with great verve and skill during the Valley campaign, during the Seven Days and Cedar Mountain. One officer remarked that “there was enough fight in old man Trimble to satisfy a herd of tigers.” [69] His abilities were such that Stonewall Jackson “had him ticked for future command of his own division.” [70] However his was severely wounded at Second Manassas and still convalescing when Lee named Allegheny Johnson to command Jackson’s old division.

Having recovered Trimble was given command of the forces that were to protect Lee’s supply line in the Shenandoah Valley, but “when he reached his new post he found no troops.” [71] This would have deterred or discouraged many an officer, but Trimble wasted no time and riding alone sought out Lee and reported to the army commander at Chambersburg on June 27th 1863. Lee who admired Trimble’s aggressiveness sent him on to Ewell, who he had previously served under as “as a sort of general officer without portfolio.” [72] The old but fiery general would get his chance in battle commanding Pender’s old division during Pickett’s Charge. Badly wounded in the assault he never commands again. He survived the war and died in 1888.

Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia would go into the Gettysburg Campaign with two new and untried corps commanders. Of nine infantry division commanders four were new to division command and another who had never commanded a division in combat. “At brigade level more than one third of the commanders lacked serious combat experience,” [73] of the infantry brigade commanders First Corps was in the best shape with ten of eleven assigned commanders having experience in command at that level, and most were of sound reputation and seasoned by combat. Second Corps was worse off, with six of thirteen assigned brigade commanders new to command, and two of the experienced brigade commanders were not competent to command at that level. Third Corps had nine of its thirteen commanders who had experience as brigade commanders; however, one of them, Brockenbrough was of little value despite being experienced. The Cavalry division too was a mixed bag of solid commanders, especially Wade Hampton but it too suffered its share of less than effective leaders and formations.

Douglas Southall Freeman wrote that the reorganization necessitated by the losses:

“involved an admixture of new units with old, it broke up many associations of long standing, and it placed veteran regiments of a large part of the army under men who were unacquainted with the soldiers and methods of General Lee. The same magnificent infantry were ready to obey Lee’s orders, but many of their superior officers were untried and were nervous in their new responsibilities.” [74]

Had the new commanders had been given a chance to work together in their new command assignments, especially those who had been promoted and or working with new subordinates or superiors before going into action, Lee might have achieved better results. But as Lee told Hood “this army would be invincible if…” In May and June of 1863 Lee did not believe that he had time to do this.

As we know, “if” is the biggest two letter word in the English language, and these men, as Barbara Tuchman noted would be “made bold by the moment, some irresolute, some carefully judicious, some paralyzed and powerless to act.”

[1] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.34

[2] Davis, Burke J.E.B. Stuart: The Last Cavalier Random House, New York 1957 p.20

[3] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.356

[4] Ibid. Davis J.E.B. Stuart p.27

[5] Ibid. Korda Clouds of Glory p.xxv

[6] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee an abridgment by Richard Harwell, Touchstone Books, New York 1997 p.101

[7] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.149

[8] Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1992 p.167

[9] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.158

[10] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.26

[11] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.54

[12] Taylor, Walter. General Lee: His campaigns in Virginia 1861-1865 With Personal Reminiscences University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln Nebraska and London, 1994 previously published 1906 p.92

[13] Ibid. Taylor General Lee p.92

[14] Longacre, Edward G. Gentleman and Soldier: The Extraordinary Life of General Wade Hampton Rutledge Hill Press, Nashville TN 2003 p.83

[15] Ibid. Davis J.E.B. Stuart p.264

[16] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.255

[17] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.198

[18] Ibid. Davis J.E.B. Stuart p.299

[19] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier pp.26-27

[20] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier p.28

[21] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier p.28

[22] Goldfield, David. America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation Bloomsbury Press, New York 2011 p.399

[23] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.64

[24] Ibid. Glatthaar, General Lee’s Army p.352

[25] Ibid. Goldfield, America Aflame p.399

[26] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.123

[27] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.770

[28] Ibid. Goldfield, America Aflame p.399

[29] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier p.265

[30] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier p.265

[31] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier p.276

[32] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.365

[33] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.259

[34] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.286

[35] Ibid. Davis J.E.B. Stuart p.159

[36] Ibid. Sears. Gettysburg p.57

[37] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.227

[38] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.178

[39] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.64

[40] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier pp.84-85

[41] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.36

[42] Ibid. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier p.275

[43] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.427

[44] Ibid. Davis J.E.B. Stuart p.54

[45] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.427

[46] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.15

[47] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.111

[48] Ibid. Davis J.E.B. Stuart p.352

[49] Ibid. Davis J.E.B. Stuart p.352

[50] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.167

[51] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.723

[52] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.532

[53] Brown, Kent Masterson Retreat from Gettysburg: Lee, Logistics, & the Pennsylvania Campaign University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 2005 p.81

[54] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.147

[55] Ibid. Freeman Lee p.306

[56] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.17

[57] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.17

[58] Ibid. Freeman Lee p.551

[59] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.371

[60] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.16

[61] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.373

[62] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.35

[63] Ibid. Sears. Gettysburg p.57

[64] Ibid. Glatthaar, General Lee’s Army p.239

[65] Ibid. Thomas Robert E. Lee p.415

[66] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.147

[67] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.129

[68] Ibid. Freeman Lee p.173

[69] Ibid. Pfanz Ewell p.152

[70] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.129

[71] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.129

[72] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.130

[73] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.217

[74] Ibid. Freeman Lee p.30