This is part two of a very long chapter in my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text. Part one was published last night and can be found here: https://padresteve.com/2014/12/11/mine-eyes-have-seen-the-glory-religion-ideology-the-civil-war-part-1/

The chapter is different because instead of simply studying the battle my students also get some very detailed history about the ideological components of war that helped make the American Civil War not only a definitive event in our history; but a war of utmost brutality in which religion drove people and leaders on both sides to advocate not just defeating their opponent, but exterminating them.

But the study of this religious and ideological war is timeless, for it helps us to understand the ideology of current rivals and opponents, some of whom we are in engaged in battle and others who we spar with by other means, nations, tribes and peoples whose world view, and response to the United States and the West, is dictated by their religion.

Yet for those more interested in current American political and social issues the period is very instructive, for the religious, ideological and political arguments used by Evangelical Christians in the ante-bellum period, as well as many of the attitudes displayed by Christians in the North and the South are still on display in our current political and social debates.

I will be posting the final part tomorrow.

Peace

Padre Steve+

Henry Clay argues for the Compromise of 1850

The Disastrous Compromise of 1850

The tensions in the aftermath of the war with Mexico escalated over the issue of slavery in the newly conquered territories brought heated calls by some southerners for secession and disunion. To preserve the Union, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, supported by the new President Millard Fillmore were able to pass the compromise of 1850 solved a number of issues related to the admission of California to the Union and boundary disputes involving Texas and the new territories. But among the bills that were contained in it was the Fugitive Slave Law, or The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The act was the device of Henry Clay which was meant to sweeten the deal for southerners. The law would “give slaveholders broader powers to stop the flow of runaway slaves northward to the free states, and offered a final resolution denying that Congress had any authority to regulate the interstate slave trade.” [1] which for all practical purposes nationalized the institution of slavery, even in Free states by forcing all citizens to assist law enforcement in apprehending fugitive slaves and voided state laws in Massachusetts, Vermont, Ohio, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island which barred state officials from aiding in the capture, arrest or imprisonment of fugitive slaves. “Congress’s law had nationalized slavery. No black person was safe on American soil. The old division of free state/slave state had vanished….” [2]

That law required all Federal law enforcement officials, even in non-slave states to arrest fugitive slaves and anyone who assisted them, and threatened law enforcement officials with punishment if they failed to enforce the law. The law stipulated that should “any marshal or deputy marshal refuse to receive such warrant, or other process, when tendered, or to use all proper means diligently to execute the same, he shall, on conviction thereof, be fined in the sum of one thousand dollars.” [3]

Likewise the act compelled citizens in Free states to “aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law, whenever their services may be required….” [4] Penalties were harsh and financial incentives for compliance attractive.

“Anyone caught providing food and shelter to an escaped slave, assuming northern whites could discern who was a runaway, would be subject to a fine of one thousand dollars and six months in prison. The law also suspended habeas corpus and the right to trial by jury for captured blacks. Judges received a hundred dollars for every slave returned to his or her owner, providing a monetary incentive for jurists to rule in favor of slave catchers.” [5]

The law gave no protection for even black freedmen. The created a new office, that of Federal Commissioner, to adjudicate the claims of slaveholders and their agents and to avoid the normal Federal Court system. No proof or evidence other than the sworn statement by of the owner with an “affidavit from a slave-state court or by the testimony of white witnesses” [6] that a black was or had been his property was required to return any black to slavery. Since blacks could not testify on their own behalf and were denied representation the act created an onerous extrajudicial process that defied imagination. The commissioners had a financial incentive to send blacks back to slavery. “If the commissioner decided against the claimant he would receive a fee of five dollars; if in favor ten. This provision, supposedly justified by the paper work needed to remand a fugitive to the South, became notorious among abolitionists as a bribe to commissioners.” [7]

Frederick Douglass said:

“By an act of the American Congress…slavery has been nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form. By that act, Mason & Dixon’s line has been obliterated;…and the power to hold, hunt, and sell men, women, and children remains no longer a mere state institution, but is now an institution of the whole United States.” [8]

On his deathbed Henry Clay praised the act, which he wrote “The new fugitive slave law, I believe, kept the South in the Union in ‘fifty and ‘fifty-one. Not only does it deny fugitives trial by jury and the right to testify; it also imposes a fine and imprisonment upon any citizen found guilty of preventing a fugitive’s arrest…” Likewise Clay depreciated the opposition noting “Yes, since the passage of the compromise, the abolitionists and free coloreds of the North have howled in protest and viciously assailed me, and twice in Boston there has been a failure to execute the law, which shocks and astounds me…. But such people belong to the lunatic fringe. The vast majority of Americans, North and South, support our handiwork, the great compromise that pulled the nation back from the brink.” [9]

The compromise had “averted a showdown over who would control the new western territories” [10] but it only delayed disunion. In arguing against the compromise South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun realized that for Southerners it did not do enough and that it would inspire abolitionists to greater efforts in their cause. He argued for permanent protection of slavery:

“He understood that slavery stood at the heart of southern society, and that without a mechanism to protect it for all time, the Union’s days were numbered.” Almost prophetically he said “I fix its probable [breakup] within twelve years or three presidential terms…. The probability is it will explode in a presidential election.” [11]

Of course it was Calhoun and not the authors of the compromise who proved correct. The leap into the abyss of disunion and civil war had only been temporarily avoided. However, none of the supporters anticipated what would occur in just six years when a train of unexpected consequences would throw an entirely new light on the popular sovereignty doctrine, and both it and the Compromise of 1850 would be wreaked with the stroke of a single judicial pen.” [12]

Religion, Ideology and the Abolitionist Movement

In the North a strident abolitionist movement took root and with each failed compromise, with each new infringement on the rights of northern free-states by the Congress, Courts and the Executive branch to appease southern slaveholders the movement gained added support. The movement developed during the 1830s in New England as a fringe movement among the more liberal elites. One wing of the movement “arose from evangelical ranks and framed its critique of bound labor in religious terms.” [13] The polarization emerged as Northern states abolished slavery as increasing numbers of influential “former slave owners such as Benjamin Franklin changed their views on the matter.” [14]

Many in the movement were inspired by the preaching of revivalist preacher Charles Finney who “demanded a religious conversion with a political potential more radical than the preacher first intended.” [15] Finney and other preachers were instrumental in the Second Great Awakening “which rekindled religious fervor in much of the nation, saw new pressure for abolition.” [16] In fact the “most important child of the Awakening, however, was the abolitionist movement, which in the 1830s took on new life, place the slavery issue squarely on the national agenda, and for the next quarter century aroused and mobilized people in the cause of emancipation.” [17]

The evangelical proponents of abolition understood this in the concept of “free will” something that the pointed out that slavery “denied one group of human beings the freedom of action necessary to free will – and therefore moral responsibility for their behavior. Meanwhile, it assigned to other human beings a degree of temporal power that virtually guaranteed their moral corruption. Both master and slave were thus trapped in a relationship that inevitably led both down the path of sin and depravity” [18]

Finney’s preaching was emboldened and expanded by the American Anti-Slavery Society founded by William Lloyd Garrison “which launched a campaign to change minds, North and South, with three initiatives, public speeches, mass mailings and petitions.” [19] Many of the speakers were seminary students and graduates of Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, who became known as “the Seventy” who received training and then “fanned out across the North campaigning in New England, Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, Indiana and Michigan” [20] where many received hostile receptions, and encountered violence. Garrison used his newspaper, The Liberator to “pledge an all-out attack on U.S. slavery.” [21] Likewise other churches such as the Presbyterians founded new educational institutions such as “Oberlin College in Ohio” which “was founded as an abolitionist institution” [22]

Theodore Parker, a Unitarian pastor and leading Transcendentalist thinker enunciated a very important theological-political analogy for many in the religious wing of the abolitionist movement which concentrated less on using chapter and verse but appealing to “the spirit of the Gospel,” [23] in as Parker’s analogy: as Jesus is to the Bible, so is the Declaration to the Constitution:

“By Christianity, I mean that form of religion which consists of piety – the love of God, and morality – the keeping of His laws. That Christianity is not the Christianity of the Christian church, nor of any sect. It is the ideal religion which the human race has been groping for….By Democracy, I mean government over all the people, by all the people and for the sake of all….This is not a democracy of the parties, but it is an ideal government, the reign of righteousness, the kingdom of justice, which all noble hearts long for, and labor to produce, the ideal whereunto mankind slowly draws near.” [24]

The early abolitionists who saw the issue framed in terms of their religious faith declared slavery a sin against God and man that demanded immediate action.” [25] For them the issue was a matter of faith and belief in which compromise of any kind including the gradual elimination of slavery or any other halfway measures were unacceptable. “William Lloyd Garrison and his fellow abolitionists believed the nation faced a clear choice between damnation and salvation,” [26] a cry that can be heard in much of today’s political debate regarding a number of social issues with religious components including abortion, gay rights and immigration. Harrison wrote that “Our program of immediate emancipation and assimilation, I maintained, was the only panacea, the only Christian solution, to an unbearable program.” [27] The abolitionists identified:

“their cause with the cause of freedom, and with the interests of large and relatively unorganized special groups such as laborers and immigrants, the abolitionists considered themselves to be, and convinced many others that they were, the sole remaining protectors of civil rights.” [28]

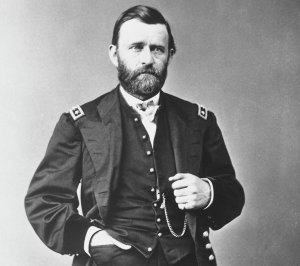

The arguments were frequently and eloquently rooted in profoundly religious terms common to evangelical Christianity and the Second Great Awakening. One of the leading historians of the era, Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, a Radical Republican and abolitionist who served as a United States Senator and Vice President in Ulysses Grant’s second administration provides a good example of this. He wrote in his post war history of the events leading to the war explaining basic understanding of the religiously minded abolitionists during the period:

“God’s Holy Word declares that man was doomed to eat his bread in the sweat of his face. History and tradition teach that the indolent, the crafty, and the strong, unmindful of human rights, have ever sought to evade this Divine decree by filching their bread from the constrained and unpaid toil of others…

American slavery reduced man, created in the Divine image, to property….It made him a beast of burden in the field of toil, an outcast in social life, a cipher in courts of law, and a pariah in the house of God. To claim for himself, or to use himself for his own benefit or benefit of wife and child, was deemed a crime. His master could dispose of his person at will, and of everything acquired by his enforced and unrequited toil.

This complete subversion of the natural rights of millions…constituted a system antagonistic to the doctrines of reason and the monitions of conscience, and developed and gratified the most intense spirit of personal pride, a love of class distinctions, and the lust of dominion. Hence a commanding power, ever sensitive, jealous, proscriptive, dominating, and aggressive, which was recognized and fitly characterized as the Slave Power…” [29]

The religious abolitionists took aim at the Southern churches and church leaders who they believed only buttressed slavery but “had become pawns of wealthy slaveholders and southern theologians apologists for oppression.” [30] As the abolitionist movement spread through Northern churches, especially those with ties to the evangelicalism of the Great Awakenings, and for “Evangelical northerners, the belief in individual spiritual and personal rights and personal religious activism made such involvement necessary.” [31]

For Baptists the issue created a deep polarization with northern Baptists mobilizing around abolitionist principles which came out of their association with English Baptists who had been at the forefront of the abolitionist movement in England where the Reverend William Knibb, who also led the fight to end slavery in Jamaica “became an impassioned defender of the human rights of blacks….his flamboyant speeches aroused the people against slavery.” [32] The Baptist Union in England sent a lengthy letter to the Baptist Triennial Convention in the United States on December 31st 1833 in which they condemned “the slave system…as a sin to be abandoned, and not an evil to be mitigated,” and in which they urged all American Baptists to do all in their power to “effect its speedy overthrow.” [33]

In 1835 two English Baptists, Francis Cox and James Hoby, who were active in that nation’s abolitionist movement with William Wilberforce came to the United States “to urge Baptists to abandon slavery. This visit and subsequent correspondence tended to polarize Baptists.” [34] In the north their visit encouraged faith based activism in abolitionist groups. In 1849 the American Baptist Anti-Slavery Convention was formed in New York and launched a polemic attack on the institution of slavery and called southern Baptists to repent in the strongest terms. They urged that the mission agencies be cleansed from “any taint of slavery…and condemned slavery in militant terms.” They called on Southern Baptists to “confess before heaven and earth the sinfulness of holding slaves; admit it to be not only a misfortune, but a crime…” and it warned that “if Baptists in the South ignored such warnings and persisted in the practice of slavery, “we cannot and dare not recognize you as consistent brethren in Christ.” [35] Such divisions we not limited to Baptists and as the decade moved on rose to crisis proportions in every evangelical denomination, provoking Kentucky Senator Henry Clay to wonder: “If our religious men cannot live together in peace, what can be expected of us politicians, very few of whom profess to be governed by the great principles of love?” [36]

The abolition movement aimed to not only stop the spread of slavery but to abolish it. The latter was something that many in the North who opposed slavery’s expansion were often either not in favor of, or indifferent to, became an issue for many after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. So long as slavery was regulated to the South most northerners showed little concern, and even though many profited by slavery, or otherwise reaped its benefits their involvement was indirect. While they may have worn clothes made of cotton harvested by slaves, while the profits of corporations that benefited from all aspects of the Southern slave economy paid the wages of northern workers and shareholders, few thought of the moral issues until they were forced to participate or saw the laws of their states overthrown by Congress.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Popularization of Abolitionism in the North

It was only after this act that the abolitionist movement began to gain traction among people in the North. The movement was given a large boost by the huge popularity of Harriett Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin “a vivid, highly imaginative, best-selling, and altogether damning indictment of slavery” [37]

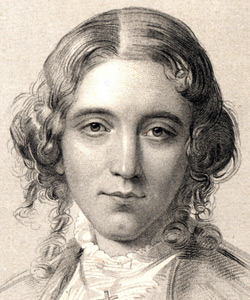

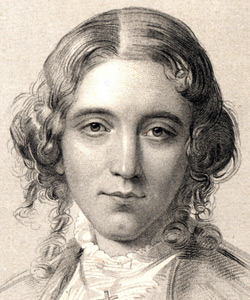

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Stowe was a well-educated writer, the daughter of the President of Lane Seminary, Lyman Beecher and wife of Calvin Ellis Stowe, a professor at the seminary. She and her family were deeply involved in the abolitionist movement and supported the Underground Railroad, even taking fugitive slaves into her home. These activities and her association with escaped slaves made a profound impact on her. She received a letter from her sister who was distraught over the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law. He sister challenged Stowe to write: “How, Hattie, if I could use a pen as you can, I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” [38]

One communion Sunday she:

“sat at the communion table of Brunswick’s First Parish Church, a vision began playing before my eyes that left me in tears. I saw an old slave clad in rags, a gentle, Christian man like the slave I had read about in American Slavery as It Is. A cruel white man, a man with a hardened fist, was flogging the old slave. Now a cruel master ordered two other slaves two other slaves to finish the task. As they laid on the whips, the old black man prayed for God to forgive them.

After church I rushed home in a trance and wrote down what I had seen. Since Calvin was away, I read the sketch to my ten- and twelve-year-old sons. They wept too, and one cried, “Oh! Mamma, slavery is the most cursed thing in the world!” I named the old slave Uncle Tom and his evil tormenter Simon Legree. Having recorded the climax of my story, I then commenced at the beginning….” [39]

The Auction, engraving from Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Many of Stowe’s characters were fiction versions of people that she actually knew or had heard about and the power of her writing made the work a major success in the United States and in Britain. The abolitionist movement gained steam and power through it and the play that issued from it. The publication of the book and its success “raised a counter indignation among Southerners because they thought Mrs. Stowe’s portrait untrue and because the North was so willing to believe it.” [40]

But despite the furor of many southerners the book gained in popularity and influenced a generation of northerners, creating a stereotype of Southern slaveholders and it caused people “to think more deeply and more personally about the implications of slavery for family, society and Christianity.” [41] The book drew many previously ambivalent to the writings of the abolitionists, and who did not normally read the accounts of escaped slaves. The vivid images in Stowe’s book “were irredeemably hostile: from now on the Southern stereotype was something akin to Simon Legree.” [42] But those images transformed the issue in the minds of many in the north as they “touched on all these chords of feeling, faith, and experience….The genius of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was that it made the personal universal, and it made the personal political as well. For millions of readers, blacks became people.” [43] One northern reader said “what truth could not accomplish, fiction did” [44] as it “put a face on slavery, and a soul on black people.” [45]

George Fitzhugh, a defended of benevolent paternalistic slavery noted Stowe’s book “was “right” concerning the “bitter treatment of slaves….Law, Religion, and Public Opinion should be invoked to punish and correct those abuses….” [46] However, such thoughts could not be spoken too openly for fear of other slaveholders who “could not calmly debate internal correction…while outside agitators advertised their supposed monstrosities.” [47] The inability to debate the issue internally made the southern visceral response to Uncle Tom’s Cabin look petty and impotent.

But others too had an effect on the debate, even escaped former slaves like Frederick Douglass. Douglass became a prominent abolitionist leader was very critical of the role of churches, especially Southern churches in the maintenance of slavery as an institution. His polemic against them in his autobiography reads like the preaching of an Old Testament prophet such as Amos, or Jeremiah railing against the corrupt religious institutions of their day:

“Indeed, I can see no reason, but the most deceitful one, for calling the religion of this land Christianity. I look upon it as the climax of all misnomers, the boldest of all frauds, and the grossest of all libels. Never was there a clearer case of “stealing the livery of the court of heaven to serve the devil in.” I am filled with unutterable loathing when I contemplate the religious pomp and show, together with the horrible inconsistencies, which every where surround me. We have men-stealers for ministers, women-whippers for missionaries, and cradle-plunderers for church members. The man who wields the blood-clotted cowskin during the week fill the pulpit on Sunday, and claims to be a minister of the meek and lowly Jesus. The man who robs me of my earnings at the end of each week meets me as a class-leader on Sunday morning, to show me the way of life, and the path of salvation. He who sells my sister, for purposes of prostitution, stands forth as the pious advocate of purity. He who proclaims it a religious duty to read the Bible denies me the right of learning to read the name of the God who made me. He who is the religious advocate of marriage robs whole millions of its sacred influence, and leaves them to the ravages of wholesale pollution. The warm defender of the sacredness of the family relation is the same that scatters whole families, — sundering husbands and wives, parents and children, sisters and brothers, — leaving the hut vacant and the heart desolate. We see the thief preaching against theft, and the adulterer against adultery. We have men sold to build churches, women sold to support the gospel, and babes sold to purchase Bibles for the poor heathen! All for the glory of God and the good of souls.”[48]

Poet Walt Whitman was radicalized by the passage of the act and in his poem Blood Money he “used the common evangelical technique of applying biblical parables to contemporary events, echoing in literary form William H. Seward’s “higher law” speech.” [49]

Of olden time, when it came to pass

That the Beautiful God, Jesus, should finish his work on earth,

Then went Judas, and sold the Divine youth,

And took pay for his body.

Cursed was the deed, even before the sweat of the clutching hand grew dry…

Since those ancient days; many a pouch enwrapping mean-

Its fee, like that paid for the Son of Mary.

Again goes one, saying,

What will ye give me, and I will deliver this man unto you?

And they make the covenant and pay the pieces of silver…

The meanest spit in thy face—they smite thee with their

Bruised, bloody, and pinioned is thy body,

More sorrowful than death is thy soul.

Witness of Anguish—Brother of Slaves,

Not with thy price closed the price of thine image;

And still Iscariot plies his trade. [50]

The leaders of the Abolitionist movement who had fought hard against acts the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision were now beginning to be joined by a Northern population that was becoming less tolerant of slavery and the status quo. For abolitionists “who had lost their youthful spiritual fervor, the crusade became a substitute for religion. And in the calls for immediate emancipation, one could hear echoes of perfectionism and millennialism.” [51]

But there was resistance of Northern theological circles to abolitionism. Charles B. Hodge, the President of Princeton Theological Seminary “supported slavery on biblical grounds, often dismissing abolitionists as liberal progressives who did not take the Bible seriously.” [52]

With the formation of the Republican Party in 1854, a party founded on opposition to the expansion of slavery in the territories found a formidable political voice and became part of a broad coalition of varied interests groups whose aspirations had been blocked by pro-slavery Democrats. These groups included “agrarians demanding free-homestead legislation, Western merchants desiring river and harbor improvements at federal expense, Pennsylvania iron masters and New England textile merchants in quest of higher tariffs.” The abolitionists also made headway in gaining the support of immigrants, “especially among the liberal, vocal, fiercely anti-slavery Germans who had recently fled the Revolution of 1848.” [53] One of those German immigrants, Carl Schurz observed that “the slavery question” was “not a mere occasional quarrel between two sections of the country, divided by a geographic line” but “a great struggle between two antagonistic systems of social organization.” [54]

Southern Religious Support of Slavery

In light of the threat posed to slavery by the emerging abolitionist movement forced slaveholders to shift their defense of slavery from it being simply a necessary evil. Slavery became “in both secular and religious discourse, the central component of the mission God had designed for the South.” [55] Like in the North where theology was at the heart of many abolitionist arguments, in the South theology was used to enshrine and defend the institution of slavery. British Evangelical-Anglican theologian Alister McGrath notes how “the arguments used by the pro-slavery lobby represent a fascinating illustration and condemnation of how the Bible may be used to support a notion by reading the text within a rigid interpretive framework that forces predetermined conclusions to the text.” [56]

Southern religion was a key component of something bigger than itself and played a role in the development of an ideology much more entrenched in the culture than the abolitionist cause did in the North, in large part due to the same Second Great Awakening that brought abolitionism to the fore in the North. “Between 1801 when he Great Revival swept the region and 1831 when the slavery debate began, southern evangelicals achieved cultural dominance in the region. Looking back over the first thirty years of the century, they concluded that God had converted and blessed their region.” [57]The Southern ideology which enshrined slavery as a key component of all areas of life was a belief system, it was a system of values, it was a worldview, or to use the more modern German term “Weltanschauung.” The Confederate worldview was the Cause. As Emory Thomas wrote in his book The Confederate Nation:

“it was the result of the secular transubstantiation in which the common elements of Southern life became sanctified in the Southern mind. The South’s ideological cause was more than the sum of its parts, more than the material circumstances and conditions from which it sprang. In the Confederate South the cause was ultimately an affair of the viscera….Questions about the Southern way of life became moral questions, and compromises of Southern life style would become concession of virtue and righteousness.” [58]

Despite the dissent of some, the “dominant position in the South was strongly pro-slavery, and the Bible was used to defend this entrenched position.” [59] The religiously based counter argument to the abolitionists was led by the former Governor of South Carolina, John Henry Hammond. Hammond’s arguments included biblical justification of blacks being biologically inferior to whites and slavery being supported in the Old Testament where the “Hebrews often practiced slavery” and in the New testament where “Christ never denounced servitude.” [60] Hammond warned:

“Without white masters’ paternalistic protection, biologically inferior blacks, loving sleep above all and “sensual excitements of all kinds when awake” would first snooze, then wander, then plunder, then murder, then be exterminated and reenslaved.” [61]

Others in the South, including politicians, pundits and preachers were preaching “that slavery was an institution sanction by God, and that even blacks profited from it, for they had been snatched out of pagan and uncivilized Africa and been given the advantages of the gospel.” [62] The basic understanding was that slavery existed because “God had providential purposes for slavery.” [63]

At the heart of the pro-slavery theological arguments was in the conviction of most Southern preachers of human sinfulness. “Many Southern clergymen found divine sanction for racial subordination in the “truth” that blacks were cursed as “Sons of Ham” and justified bondage by citing Biblical examples.” [64] But simply citing scripture to justify the reality of a system that they repeated the benefit is just part of the story for the issue was far greater than that. The theology that justified slavery also, in the minds of many Christians in the north justified what they considered “the hedonistic aspects of the Southern life style.” [65] This was something that abolitionist preachers continually emphasized, criticizing the greed, sloth and lust inherent in the culture of slavery and plantation life, and was an accusation that Southern slaveholders, especially evangelicals took umbrage, for in their understanding good men could own slaves. Their defense was rooted in their theology and the hyper-individualistic language of Southern evangelicalism gave “new life to the claim that good men could hold slaves. Slaveholding was a traditional mark of success, and a moral defense of slavery was implicit wherever Americans who considered themselves good Christians held slaves.” [66] The hedonism and fundamentalism that existed in the Southern soul, was the “same conservative faith which inspired John Brown to violence in an attempt to abolish slavery…” [67]

Slave owners frequently expressed hostility to independent black churches and conducted violence against them, and “attacks on clandestine prayer meetings were not arbitrary. They reflected the assumption (as one Mississippi slave put it) “that when colored people were praying [by themselves] it was against them.” [68] But some Southern blacks accepted the basic tenets do slave owner-planter sponsored Christianity. Frederick Douglass later wrote “many good, religious colored people who were under the delusion that God required them to submit to slavery and wear their chains with weakness and humility.” [69]

The political and cultural rift began to affect entire church denominations. The heart of the matter went directly to theology, in this case the interpretation of the Bible in American churches. The American Protestant and Evangelical understanding was rooted in the key theological principle of the Protestant Reformation, that of Sola Scripura, which became an intellectual trap for northerners and southerners of various theological stripes. Southerners believed that they held a “special fidelity to the Bible and relations with God. Southerners thought abolitionists either did not understand the Bible or did not know God’s will, and suspected them of perverting both.” [70]The problem was then, as it is now that:

“Americans favored a commonsense understanding of the Bible that ripped passages out of context and applied them to all people at all times. Sola scriptura both set and limited terms for discussing slavery and gave apologists for the institution great advantages. The patriarchs of the Old Testament had owned slaves, Mosaic Law upheld slavery, Jesus had not condemned slavery, and the apostles had advised slaves to obey their masters – these points summed up and closed the case for many southerners and no small number of northerners.” [71]

In the early decades of the nineteenth century there existed a certain confusion and ambivalence to slavery in most denominations. The Presbyterians exemplified this when in 1818 the “General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, while opposing slavery against the law of God, also went on record as opposing abolition, and deposed a minister for advocating abolition.” [72] There were arguments by some American Christians including some Catholics, Lutherans, Episcopalians and others to offer alternative ways to “interpreting and applying scripture to the slavery question, but none were convincing or influential enough to force debate” [73] out of the hands of literalists.

However the real schisms between the Northern and Southern branches of the major denominations began to emerge in the mid to late 1830s with the actual breakups coming in the 1840s. The first to split were the Methodists when in “1844 the Methodist General Conference condemned the bishop of Georgia for holding slaves, the church split and the following year saw the birth of the Methodist Episcopal Church.” [74] Not all Methodists in the South agreed with this split and Methodist abolitionists in the South “broke away from mainline Methodism to form the Free Methodist Church.” [75]

The Baptists were next, when the Foreign Mission Board “refused to commission a candidate who had been recommended by the Georgia Baptist Convention, on the ground that he owned slaves” [76] resulting in the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention. The Baptist split is interesting because until the early 1800s there existed a fairly strong anti-slavery movement in states such as Kentucky, while in 1790 the General Committee of Virginia “adopted a statement calling slavery “a violent deprivation of the rights of nature, and inconsistent with a republican government; and therefore [we] recommend it to our brethren to make use of every legal measure, to extirpate the horrid evil from the land.” [77]

However, in many parts of the Deep South there existed no such sentiment and in South Carolina noted Baptist preachers including “Richard Furman, Peter Bainbridge, and Edmund Botsford were among the larger slaveholders.” [78] Furman wrote a defense of slavery in 1822 where he made the argument that “the right of holding slaves is clearly established in the Holy Scriptures by precept and example.” [79] After a number of slave uprisings, including the Nat Turner Revolt in Virginia, pro-slavery voices “tended to silence any remaining antislavery voices in the South.” [80]

These voices grew more ever more strident and in 1835 the Charleston Association “adopted a militant defense of slavery, sternly chastising abolitionists as “mistaken philanthropists, and denuded and mischievous fanatics.” [81] Those who met in Augusta Georgia to found the new Southern Baptist Convention indicated that “the division was “painful” but necessary because” our brethren have pressed upon every inch of our privileges and our sacred rights.” [82] Since the Baptist split was brought about by the refusal of the Triennial Convention to appoint slaveholders as foreign missionaries the new convention emphasized the theological nature of their decision:

“Our objects, then, are the extension of the Messiah’s kingdom, and the glory of God. Not disunion with any of his people; not the upholding of any form of civil rights; but God’s glory, and Messiah’s increasing reign; in the promotion of which, we find no necessity for relinquishing any of our civil rights. We will never interfere with what is Caesar’s. We will not compromit what is God’s.” [83]

Of course, to the Baptists who met at Augusta, what was Caesar’s was obviously the institution of slavery.

The last denomination to officially split was the Presbyterians in 1861 who, “reflecting the division of the nation, the Southern presbyteries withdrew from the Presbyterian Church and founded their own denomination.” [84] The split in the Presbyterian Church had been obvious for years despite their outward unity, some of the Southern pastors and theologians were at the forefront of battling their northern counterparts for the theological high ground that defined just whose side God was on. James Henley Thornwell presented the conflict between northern evangelical abolitionists and southern evangelical defenders of slavery in Manichean terms. He believed that abolitionists attacked religion itself.

“The “parties in the conflict are not merely abolitionists and slaveholders,…They are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, jacobins, on one side, and friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battle ground – Christianity and Atheism as the combatants; and the progress of humanity at stake.” [85]

Robert Lewis Dabney, a southern Presbyterian pastor who later served as Chief of Staff to Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign and at Seven Pines and who remained a defender of slavery long after the war was over wrote that:

“we must go before the nation with the Bible as the text and ‘Thus saith the Lord’ as the answer….we know that on the Bible argument the abolition party will be driven to reveal their true infidel tendencies. The Bible being bound to stand on our side, they have to come out and array themselves against the Bible. And then the whole body of sincere believers at the North will have to array themselves, though unwillingly, on our side. They will prefer the Bible to abolitionism.” [86]

Southern churches and church leaders were among the most enthusiastic voices for disunion and secession. They labeled their Northern critics, even fellow evangelicals in the abolition movement as “atheists, infidels, communists, free-lovers, Bible-haters, and anti-Christian levelers.” [87] The preachers who had called for separation from their own national denominations years before the war now “summoned their congregations to leave the foul Union and then to cleanse their world.” [88] Thomas R.R. Cobb, a Georgia lawyer, an outspoken advocate of slavery and secession, who was killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg, wrote proudly that Secession “has been accomplished mainly by the churches.” [89]

The Reverend William Leacock of Christ Church, New Orleans declared in his Thanksgiving sermon “Our enemies…have “defamed” our characters, “lacerated” our feelings, “invaded “our rights, “stolen” our property, and let “murderers…loose upon us, stimulated by weak or designing or infidel preachers. With “the deepest and blackest malice,” they have “proscribed” us “as unworthy members… of the society of men and accursed before God.” Unless we sink to “craven” beginning that they “not disturb us,…nothing is now left us but secession.” [90]

The Religious Divide Becomes Political

The breakups of the major Protestant denominations boded ill for the country, in fact the true believers in their cause be it the abolition of slavery or the maintenance and expansion of it were among the most strident politically. “For people of faith these internecine schisms were very troubling. If citizens could not get along in the fellowship of Christ, what did the future hold for the nation?” [91] Both of the major political parties of the 1840s, the Democrats and the Whigs found themselves ever more led by religion as the “fissures among evangelicals, the conflicts between Protestants and Catholics, the slavery debates, and the settlement of the West placed religion at the forefront of American politics.” [92] Of course it was slavery that became the overriding issue as decade moved forward and the divisions among the faithful became deeper.

A Cincinnati minister who preached against secession “citing Absalom, Jeroboam, and Judas” as examples, argued that the “Cause of the United States” and the Cause of Jehovah” were identical…and insisted that “a just defensive war” against southern secessionists is “one of the prominent ways by which the Lord will introduce the millennial day.” [93] In the South many ministers became active in politics and men who at one time had been considered moderates began to speak “in the language of cultural warfare.” Mississippi Episcopal Bishop William Mercer Green denounced the “restless, insubordinate, and overbearing spirit of Puritanism” that was destroying the nation.” [94]

Some political leaders who had worked to craft compromises like South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun were concerned and observed that the evangelical denominations which were splitting had “contributed greatly to strengthen the bond of the Union.” If all bonds were loosed, he worried, “nothing will be left to hold the Union together except force.” [95] Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln, both who would be considered moderates on the issue of slavery in the late 1840s and early 1850s came to sharply different philosophical and theological understandings of the unfolding dissolution of the country. Davis as early as 1848 was defending slavery as “a common law right to property in the services of man; its origin is in Divine decree – the curse on the graceless sons of Noah.” But Lincoln condemned the expansion of the institution did so in decidedly theological terms, noting that “Slavery is founded in the selfishness of man’s nature…opposition to it is in his love of justice…. Repeal all past human history, you cannot repeal human nature. It will still be the abundance of man’s heart, that slavery extension is wrong.” [96]

God’s Chosen People and the Confederate Union of Church and State

Perhaps more than anything the denominational splits helped prepare the Southern people as well as clergy for secession and war. They set precedent by which Southerners left establish national organizations. When secession came, “the majority of young Protestant preachers were already primed by their respective church traditions to regard the possibilities of political separation from the United States without undue anxiety.” [97]

One of the most powerful ideological tools since the days of the ancients has been the linkage of religion to the state. While religion has always been a driving force in American life since they days of the Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, especially in the belief about the destiny of the nation as God’s “Chosen People” it was in the South where the old Puritan beliefs took firm root in culture, society, politics and the ideology which justified slavery and became indelibly linked to Southern nationalism. “Confederate independence, explained a Methodist tract quoting Puritan John Winthrop, was intended to enable the South, “like a city set on a hill’ [to] fulfill her God given mission to exalt in civilization and Christianity the nations of the earth.” [98]

Religion and the churches “supplied the overarching framework for southern nationalism. As Confederates cast themselves as God’s chosen people” [99] and the defense of slavery was a major part of this mission of the chosen people. A group of 154 clergymen “The Clergy of the South” “warned the world’s Christians that the North was perpetuating a plot of “interference with the plans of Divine Providence.” [100] A Tennessee pastor bluntly stated in 1861 that “In all contests between nations God espouses the cause of the Righteous and makes it his own….The institution of slavery according to the Bible is right. Therefore in the contest between the North and the South, He will espouse the cause of the South and make it his own.” [101]

The effect of such discourse on leaders as well as individuals was to unify the struggle as something that linked the nation to God, and God’s purposes to the nation identifying both as being the instruments of God’s will and Divine Providence:

“Sacred and secular history, like religion and politics, had become all but indistinguishable… The analogy between the Confederacy and the chosen Hebrew nation was invoked so often as to be transformed into a figure of everyday speech. Like the United States before it, the Confederacy became a redeemer nation, the new Israel.” [102]

This theology also motivated men like the convinced hard line Calvinist-Presbyterian, General Stonewall Jackson on the battlefield. Jackson’s brutal, Old Testament understanding of the war caused him to murmur: “No quarter to the violators of our homes and firesides,” and when someone deplored the necessity of destroying so many brave men, he exclaimed: “No, shoot them all, I do not wish them to be brave.” [103]

In effect: “Slavery became in secular and religious discourse, the central component of the mission God had designed for the South….The Confederates were fighting a just war not only because they were, in the traditional framework of just war theory, defending themselves against invasion, they were struggling to carry out God’s designs for a heathen race.” [104]

From “the beginning of the war southern churches of all sorts with few exceptions promoted the cause militant” [105] and supported war efforts, the early military victories of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and the victories of Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley were celebrated as “providential validations of the cause that could not fail…” Texas Methodist minister William Seat wrote: “Never surely since the Wars of God’s ancient people has there been such a remarkable and uniform success against tremendous odds. The explanation is found in the fact that the Lord goes forth to fight against the coercion by foes of his particular people. Thus it has been and thus it will be to the end of the War.” [106]

This brought about a intertwining of church and state authority, a veritable understanding of theocracy as “The need for the southern people to acknowledge God’s authority was bound up with a legitimation of the authority of clerical and civil rulers. Christian humility became identified with social and political deference to both God and Jefferson Davis.” [107]

Jefferson Davis and other leaders helped bolster this belief:

“In his repeated calls for God’s aid and in his declaration of national days of fasting, humiliation, and prayer on nine occasions throughout the war, Jefferson Davis similarly acknowledged the need for a larger scope of legitimization. Nationhood had to be tied to higher ends. The South, it seemed, could not just be politically independent; it wanted to believe it was divinely chosen.” [108]

Davis’s actions likewise bolster his support and the support for the war among the clergy. A clergyman urged his congregation that the people of the South needed to relearn “the virtue of reverence- and the lesson of respecting, obeying, and honoring authority, for authority’s sake.” [109]

Confederate clergymen not only were spokesmen and supporters of slavery, secession and independence, but many also shed their clerical robes and put on Confederate Gray as soldiers, officers and even generals fighting for the Confederacy. Bishop Leonidas Polk, the Episcopal Bishop of Louisiana, who had been a classmate of Jefferson Davis at West Point was commissioned as a Major General and appointed to command the troops in the Mississippi Valley. Polk did not resign his ecclesiastical office, and “Northerners expressed horror at such sacrilege, but Southerners were delighted with this transfer from the Army of the Lord.” [110] Lee’s chief of Artillery Brigadier General Nelson Pendleton was also an academy graduate and an Episcopal Priest. By its donations of “everything from pew cushions to brass bells, Southern churches gave direct material aid to the cause. Among all the institutions in Southern life, perhaps the church most faithfully served the Confederate Army and nation.” [111] Southern ministers “not only proclaimed the glory of their role in creating the war but also but also went off to battle with the military in an attempt to add to their glory.” [112]

Sadly, the denominational rifts persisted until well into the twentieth century. The Presbyterians and Methodists both eventually reunited but the Baptists did not, and eventually “regional isolation, war bitterness, and differing emphasis in theology created chasms by the end of the century which leaders of an earlier generation could not have contemplated.” [113] The Southern Baptist Convention is now the largest Protestant denomination in the United States and many of its preachers are active in often divisive conservative social and political causes. The denomination that it split from, the American Baptist Convention, though much smaller remains a diverse collection of conservative and progressive local churches. Some of these are still in the forefront of the modern civil rights movement, including voting rights, women’s rights and LGBT issues, all of which find some degree of opposition in the Southern Baptist Convention.

But the religious dimensions were far bigger than denominational disagreements about slavery; religion became one of the bedrocks of Confederate nationalism. The Great Seal of the Confederacy had as its motto the Latin words Deo Vindice which can be translated “With God as our Champion” or “Under God [Our] Vindicator.” The issue was bigger than independence itself, it was intensely theological and secession “became an act of purification, a separation from the pollutions of decaying northern society, that “monstrous mass of moral disease,” as the Mobile Evening News so vividly described it.” [114]

The arguments found their way into the textbooks used in schools throughout the Confederacy. “The First Reader, For Southern Schools assured its young pupils that “God wills that some men should be slaves, and some masters.” For older children, Mrs. Miranda Moore’s best-selling Geographic Reader included a detailed proslavery history of the United States that explained how northerners had gone “mad” on the subject of abolitionism.” [115] The seeds of future ideological battles were being planted in the hearts of white southern children by radically religious ideologues, just as they are today in the Madrassas of the Middle East.

While the various theological and ideological debates played out and fueled the fires of passion that brought about the war, and provided great motivation, especially to Confederates during the war, that their cause was righteous, other very real world decisions and events in terms of politics, law and lawlessness further inflamed passions.

The Deepening Divide: The Dred Scott Decision

As the 1850s wore on the divisions over slavery became deeper and voices of moderation retreated. The trigger for the for the worsening of the division was the political battle regarding the expansion of slavery, even the status of free blacks in the north who were previously slaves, over whom their owners asserted their ownership. Southerners considered the network to help fugitive slaves escape to non-slave states, called the Underground Railroad “an affront to the slaveholders pride” and “anyone who helped a man or woman escape bondage was simply a thief” who had robbed them of their property and livelihood, as an “adult field hand could cost as much as $2000, the equivalent of a substantial house.” [116]

In 1856 the Supreme Court, dominated by southern Democrats ruled in favor of southern views in the Dred Scott decision one pillar of which gave slavery the right to expand by denying to Congress the power to prohibit slavery in Federal territories. The decision was momentous but it was a failure, but it was a disaster for the American people. It solved nothing and further divided the nation:

“In the South, for instance, it encouraged southern rights advocates to believe that their utmost demands were legitimatized by constitutional sanction and, therefore, to stiffen their insistence upon their “rights.” In the North, on the other hand, it strengthened a conviction that an aggressive slavocracy was conspiring to impose slavery upon the nation, and that any effort to reach an accommodation with such aggressors was futile. While strengthening the extremists, it cut the ground from under the moderates.” [117]

The decision in the case is frightening when one looks upon its tenor and implications. The majority opinion which was written by Chief Justice Roger Taney was chilling, not only in its views of race, but the fact that blacks were perpetually property without the rights of citizens. Taney wrote:

“Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen?…It is absolutely certain that the African race were not included under the name of citizens of a state…and that they were not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word “citizens” in the Constitution, and therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings, who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remain subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them” [118]

The effect of the ruling on individuals and the states was far reaching. “No territorial government in any federally administered territory had the authority to alter the status of a white citizen’s property, much less to take that property out of a citizen’s hands, without due process of law or as punishment for some crime.” [119] Free slaves were no longer safe, even in Free States from the possibility of being returned to slavery, because they were property.

Chief Justice Roger Taney, Author of the Dred Scott Decision

But the decision had been influenced by President-Elect James Buchanan’s secret intervention in the Supreme Court deliberations two weeks before his inauguration. Buchanan hoped by working with the Justices that he save the Union from breaking apart by appeasing slave owners and catering to their agenda. “The president-elect wanted to know not only when, but if the Court would save the new administration and the Union from the issue of slavery in the territories. Would the judges thankfully declare the explosive subject out of bounds, for everyone who exerted federal power? The shattering question need never bother President Buchanan.” [120] In his inaugural address he attempted to camouflage his intervention and “declared that the Court’s decision, whatever it turned out to be, would settle the slavery issue forever.” [121]

But Buchanan was mistaken, the case made the situation even more volatile as it impaired “the power of Congress- a power which had remained intact to this time- to occupy the middle ground.” [122] Taney’s decision held that Congress “never had the right to limit slavery’s expansion, and that the Missouri Compromise had been null and void on the day of its formulation.” [123]

The Court’s decision “that a free negro was not a citizen and the decision that Congress could not exclude slavery from the territories were intensely repugnant to many people in the free states” [124] and it ignited a firestorm in the north where Republicans now led by Abraham Lincoln decried the decision and southerners basked in their judicial victory. Northerners quite rightly feared that an activist court would rule to deny their states the right to forbid slavery. As early as 1854 Lincoln posed the idea that the Declaration of Independence was “the standard maxim of free society …constantly spreading and deepening its influence,” ultimately applicable “to peoples of all colors everywhere.” [125]

But after the Dred Scott decision Lincoln warned that the Declaration was being cheapened and diluted. Lincoln noted:

“Our Declaration of Independence was held sacred by all, and thought to include all” Lincoln declared, “but now, to aid in making the bondage of the Negro universal and eternal, it is assaulted, and sneered at, and construed, and hawked at, and torn, till, its framers could ride from their graves, they could not recognize it at all.” [126]

Not only that, Lincoln asked the logical question regarding Taney’s judicial activism. How long would it be, asked Abraham Lincoln, before the Court took the next logical step and ruled explicitly that:

“the Constitution of the United States does not permit a state to exclude slavery from its limits?” How far off was the day when “we shall lie down pleasantly thinking that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State?” [127]

Lincoln discussed the ramification of the ruling for blacks, both slave and free:

“to aid in making the bondage of the Negro universal and eternal….All the powers of the earth seem rapidly combining against him. Mammon is after him; ambition follows, and philosophy follows, and the theology of the day is fast joining the cry. They have him in his prison house;…One after another they have closed the heavy doors upon him…and they stand musing as to what invention, in all the dominions of mind and matter, can be produced the impossibility of his escape more complete than it is.” [128]

Lincoln was not wrong in his assessment of the potential effects of the Dred Scott decision on Free States. “In 1852 a New York judge upheld the freedom of eight slaves who had left their Virginia owner while in New York City on their way to Texas.” [129] The Dred Scott decision brought that case, Lemon v. The People back to the fore and “Virginia decided to take the case to the highest New York court (which upheld the law in 1860) and would have undoubtedly appealed it to Taney’s Supreme Court had not secession intervened.” [130]

In response to the decision the advocates of the expansion of slavery not only insisted on its westward expansion in Federal territories but “in their must exotic fantasy, proslavery expansionists would land several dozen or several hundred American freedom fighters on Central or South American shores.” [131] Their targets would include Panama, Nicaragua, and Cuba as well. In 1855 one of these adventurers was William Walker who “sailed with about sixty followers (“the immortals”) to participate in a civil war in Nicaragua. Within little more than a year, he made himself President, and Franklin Pierce recognized his government.” [132] In 1857 Jefferson Davis further provoked northern ire when he insisted that “African Slavery as it exists in the United States is a moral, a social, and a political blessing.” [133]

Southern leaders poured political, human and economic capital into the struggle for the imposition of slavery on the Kansas Territory following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. For the South a pro-slavery victory in Kansas meant “two new U.S. Senators for the South. If a free labor Kansas triumphed, however, the North would gain four senators: Kansas’s immediately and Missouri’s soon.” [134]

To be continued tomorrow….

Notes

[1] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.68

[2] Goldfield, David America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation Bloomsbury Press, New York, London New Delhi and Sidney 2011 p.71

[3] ______________Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 retrieved from the Avalon Project, Yale School of Law http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/fugitive.asp 11 December 2014

[4] Ibid. Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

[5] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.71

[6] McPherson, James. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1988 p.80

[7] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.80

[8] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.72

[9] Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.94

[10] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.71

[11] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.64

[12] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.71

[13] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.93

[14] McGrath, Alister Christianity’s Dangerous Idea: The Protestant Revolution A History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2007 p.324

[15] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.289

[16] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[17] Huntington, Samuel P. Who Are We? America’s Great Debate The Free Press, Simon and Schuster Europe, London 2004 p.77

[18] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.93

[19] Ibid. Egnal Clash of Extremes:pp.125-126

[20] Ibid. Egnal Clash of Extremes p.125

[21] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.12

[22] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[23] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.14

[24] Wills, Garry Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York 1992

[25] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.13

[26] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.13

[27] Oates, Stephen B. Editor The Approaching Fury: Voices of the Storm, 1820-1861 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 1997 p.36

[28] Stampp, Kenneth M. editor The Causes of the Civil War 3rd Revised Edition A Touchstone Book published by Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1991 p.23

[29] Ibid. Stampp The Causes of the Civil War p.29

[30] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.13

[31] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.35

[32] McBeth, H. Leon The Baptist Heritage Broadman Press, Nashville TN 1987 p.301

[33] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.301

[34] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[35] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage pp.384-385

[36] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.35

[37] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.94

[38] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.75

[39] Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.120

[40] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.94

[41] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.83

[42] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.94

[43] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.79

[44] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.79

[45] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.83

[46] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.48

[47] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.49

[48] Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape From Bondage, and His Complete History. New York: Collier Books, 1892. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/lincolns-inconsistencies/ December 9th 2014

[49] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.72

[50] Whitman, Walt Blood Money March 22nd 1850 retrieved from the Walt Whitman Archive http://www.whitmanarchive.org/published/periodical/poems/per.00089 11 December 2014

[51] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.13

[52] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[53] Catton, William and Bruce, Two Roads to Sumter: Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson Davis and the March to Civil War McGraw Hill Book Company New York 1963, Phoenix Press edition London p.123

[54] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.15

[55] Gallagher, Gary W. The Confederate War: How Popular Will, Nationalism and Military Strategy Could not Stave Off Defeat Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 1999 p.67

[56] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[57] Daly, John Patrick When Slavery Was Called Freedom: Evangelicalism, Proslavery, and the Causes of the Civil War The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington KY 2002 p.69

[58] Thomas, Emory The Confederate Nation 1861-1865 Harper Perennial, New York and London 1979 p.4

[59] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[60] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.29

[61] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume One p.29

[62] Gonzalez, Justo L. The History of Christianity Volume 2: The Reformation to the Present Day Harper and Row Publishers San Francisco 1985 p.251

[63] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.54

[64] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.22

[65] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.22

[66] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.30

[67] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.22

[68] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.116

[69] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.116

[70] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.60

[71] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.14

[72] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[73] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.14

[74] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[75] Ibid. McGrath Christianity’s Dangerous Idea p.324

[76] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[77] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.383

[78] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[79] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[80] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[81] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage p.384

[82] Shurden, Walter B Not a Silent People: The Controversies that Have Shaped Southern Baptists Broadman Press, Nashville TN 1972 p.58

[83] Ibid. Shurden Not a Silent People p.58

[84] Ibid. Gonzalez The History of Christianity Volume 2 p.251

[85] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.13

[86] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.14

[87] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.97

[88] Freehling, William. The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2007 p.460

[89] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.39

[90] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II p.462

[91] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.35

[92] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.36

[93] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples pp.39-40

[94] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.40

[95] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.35

[96] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.61

[97] Brinsfield, John W. et. al. Editor, Faith in the Fight: Civil War Chaplains Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg PA 2003 p.67

[98] Faust, Drew Gilpin The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London p.27

[99] Ibid. Gallagher The Confederate War pp.66-67

[100] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.145

[101] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.138

[102] Ibid. Faust The Creation of Confederate Nationalism p.29

[103] Fuller, J.F.C. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1957

[104] Ibid. Faust, The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South p.60

[105] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation 1861-1865 pp.245-246

[106] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom pp.145 and 147

[107] Ibid. Faust The Creation of Confederate Nationalism p.26

[108] Ibid. Faust The Creation of Confederate Nationalism p.33

[109] Ibid. Faust The Creation of Confederate Nationalism p.32

[110] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume One: Fort Sumter to Perryville Random House, New York 1963 1958 p.87

[111] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.246

[112] Ibid. Daly When Slavery Was Called Freedom p.142

[113] Ibid. McBeth The Baptist Heritage pp.392-393

[114] Ibid. Faust The Creation of Confederate Nationalism p.30

[115] Ibid. Faust The Creation of Confederate Nationalism p.62

[116] Goodheart, Adam. Moses’ Last Exodus in The New York Times: Disunion, 106 Articles from the New York Times Opinionator: Modern Historians Revist and Reconsider the Civil War from Lincoln’s Election to the Emancipation Proclamation Edited by Ted Widmer, Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, New York 2013 p.15

[117] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.291

[118] Guelzo Allen C. Fateful Lightening: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2012 p.91

[119] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening pp.91-92

[120] Freehling, William. The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2007 p.115

[121] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.109

[122] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.291

[123] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.210

[124] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.279

[125] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.139

[126] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.93

[127] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.211

[128] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.139

[129] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.181

[130] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.181

[131] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.145

[132] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.193

[133] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.142

[134] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.124