Friends of Padre Steve’s World

This week I have been posting about Gettysburg and the solemn observance of Independence Day on 4 July, 1863.

So tonight I will repost a final article from my Gettysburg text. It deals with the human cost of the Battle of Gettysburg. In his Gettysburg Address Abraham Lincoln said:

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.”

I am a now recareer military officer who suffers from PTSD, TBI and other afflictions after serving in Iraq’s Al Anbar Province in 2007-2008. I have seen firsthand the terrible effects of war. I am also a historian and I have served as Assistant Professor at a major military staff college which helps educate senior military officers from this country and other countries. In that capacity I taught ethics as well as led the Gettysburg Staff ride, or study of the Battle of Gettysburg. When whenever I teach about Gettysburg or any other military campaign, I always attempted to deal with the human cost of war and its attendant afflictions.

Gettysburg was the most costly battle ever fought on the American continent. Around 50,000 men were killed or wounded there in three days of battle. William Tecumseh Sherman noted that “war is hell.” I agree, there is nothing romantic about it. The effects of war last generations. Although we spent over 20 years at war, war itself is an abstract concept to most Americans. It is fought by professionals and only experienced by most Americans on the news, movies or most the banal manner, video games; thus the cost in human terms is not fully appreciated, and nor can it be, we are far too insulated from it. Over the past forty plus years our politicians have insulated the public from war, and in doing so they have ensured that we remained in perpetual war which benefits no one. That is a big reason why I write so much about it, not to glorify or romanticize it, but to try in some war to help make it real to my readers. This is a another draft chapter from my Gettysburg text, and as a side note, the pictures, with the exception of the color photos taken by me at the Soldier’s Cemetery, all were taken after the battle.

Walt Whitman Wrote:

“Ashes of soldiers South or North, As I muse retrospective murmuring a chant in thought, The war resumes, again to my sense your shapes, And again the advance of the armies. Noiseless as mists and vapors, From their graves in the trenches ascending, From cemeteries all through Virginia and Tennessee, From every point of the compass out of the countless graves, In wafted clouds, in myriads large, or squads of twos or threes or single ones they come, And silently gather round me…”

Too often we look at distant battles and campaigns in terms of strategy, operations, tactics, leadership and the weaponry employed. Likewise we might become more analytical and look at the impact of the battle or campaign in the context of the war it was fought, or in the manner in which the tactics or weapons used revolutionized warfare. Sometimes in our more reflective moments we might look at individual bravery or sacrifice, often missing in our analysis is the cost in flesh and blood.

Admittedly the subject is somewhat macabre. But with the reality being that very few people in the United States, Canada or Western Europe have experienced the terrible brutality of war it is something that we should carefully consider any time the nation commits itself to war. By we, I mean all citizens, including the many soldiers, sailors and airmen who never see the personally see people they kill, or walk among the devastation caused by the highly advanced, precision weapons that they employ from a great distance, sometimes thousands of miles. In some parts of our military we have men and women who have the mission of targeting and killing enemies and then walking home to their families, but in the Civil War killing in combat “remained essentially intimate; soldiers were able to see each other’s faces and to know whom they had killed.” [1]

While the words of William Tecumseh Sherman that “War is Hell” are as true as when he spoke them; the tragic fact is that for most people war is an abstract concept, antiseptic and unreal; except for the occasional beheading of a hostage by Islamic militants or the videos shot by the perpetrators of crimes against humanity on the internet. Thus the cost of war and its attendant cost in lives, treasure and to the environment are not real to most people in the West.

We use words to describe the business of war which dehumanize the enemy, and we describe their deaths in words more palatable to us. Dave Grossman, the army infantry officer who has spent his post military life writing about the psychology of war and killing wrote:

“Even the language of men at war is the full denial of the enormity of what they have done. Most solders do not “kill,” instead the enemy was knocked over, wasted, greased, taken out, and mopped up. The enemy is hosed, zapped, probed, and fired on. The enemy’s humanity is denied, and he becomes a strange beast called a Jap, Reb, Yank, dink, slant, or slope. Even the weapons of war receive benign names- Puff the Magic Dragon, Walleye, TOW, Fat Boy, Thin Man- and the killing weapon of the individual soldier becomes a piece or a hog, and a bullet becomes a round.” [2]

We can now add the terms Haji and Raghead to Grossman’s list of dehumanizing terms for our opponents from our most recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The words of Guy Sager in his classic work The Forgotten Soldier about World War Two on the Eastern front is lost on many that study war:

“Too many people learn about war with no inconvenience to themselves. They read about Verdun or Stalingrad without comprehension, sitting in a comfortable armchair, with their feet beside the fire, preparing to go about their business the next day, as usual…One should read about war standing up, late at night, when one is tired, as I am writing about it now, at dawn, while my asthma attack wears off. And even now, in my sleepless exhaustion, how gentle and easy peace seems!” [3]

In an age where so few have served in the military and even few have seen combat in some way shape or form many who study war are comfortable experts who learn about war with no inconvenience to themselves. When I hear men and women, the pundits, politicians and preachers, that Trinity of Evil who constantly exhort governments and peoples to go to war for causes, places or conflicts that they have little understanding of from the comfort of their living rooms or television studios I grow weary. I fully comprehend the words of Otto Von Bismarck who said: “Anyone who has ever looked into the glazed eyes of a soldier dying on the battlefield will think hard before starting a war.” [4]

As a historian who also is a military chaplain who has seen war I struggle with what Sager said. Thus when I read military history, study and write about particular battles or engagements, or conduct staff rides as like the Gettysburg trip that we are embarking on, the human cost is always present in my mind. The fact that I still suffer the effects of PTSD including night terrors and chronic insomnia keeps what I do in good focus, and prevents me from being a comfortable expert.

Thus, it is my view, to conduct a staff ride, to walk the battlefield; especially in somewhat uncomfortable weather is a good thing. It connects us more in at least a small way to the men that fought there, died there, or brought home wounds that changed them forever.

To walk a battlefield where tens of thousands of men were killed and wounded is for me a visit to hallowed ground. I have felt that at Waterloo, Verdun, Arnhem, Normandy, the Bulge, the West Wall, the Shuri Line on Okinawa, Antietam, Chancellorsville, Stone’s River, and of course the battlefield which I have visited more than any in my life, Gettysburg. There are times when I walk these fields that I am overcome with emotion. This I think is a good thing, for as an American who has family ties to the Civil War, Gettysburg in particular is hallowed ground.

In doing this I try to be dispassionate in how I teach and while dealing with big issues that my students will face as Joint Staff Officers. Some of them will become Flag or General Officers, with the responsibility of advising our nation’s leaders as well planning and conducting the military operations on which the lives of thousands or maybe hundreds of thousands of people depend. Thus I do feel a certain responsibility to teach not only the strategy and other important military aspects of this campaign, but also the cost in human lives and ethical considerations. I take this work seriously because it forces us to remember what war is about and its nature, which Clausewitz wrote is “a paradoxical trinity-composed of primordial violence, hatred and enmity…” [5]which William Tecumseh Sherman so rightly understood without the euphemisms that we so frequently use to describe it: “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it….”

As the sun set on the evening of July 3rd 1863 the battered Army of Northern Virginia and the battered but victorious Army of the Potomac tended their wounds, buried their dead and prepared for what might happen next. On that afternoon it was as if “the doors of Hell had shut” and the next day, the Glorious 4th of July “The heavens opened, and a thunderstorm of biblical proprotions drenched the battlefield, soaking dead, wounded and able-bodied men equally.” [6]

Following the disastrous attack aimed at the Union center, Lee and his surviving commanders prepared for an expected Union counter attack. However, George Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac who had correctly anticipated Lee’s assault decided not to gamble on a counter attack, though it was tempting. He knew too well the tenacity and skill of the Confederate commanders and soldiers on the defense and did not want to risk a setback that might give Lee another chance, thus “the two sides stared at each other, each waiting for the other to resume the fighting, neither did.” [7]

As the Confederate army retreated and Meade’s army pursued another army remained at Gettysburg, “an army of the wounded, some 20,350 in number, a third of them Confederate….” Just 106 surgeons were spared from the Army of the Potomac and “the comparatively few overburdened surgeons and attendants now on duty still labored every day to the point of exhaustion.”[8] These overworked men were aided by local volunteers as well as members of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, the Christian Commission and the Sisters of Charity. These men and women “brought organization to the hospitals, relief to the medical staffs and the local volunteers, and immense comfort to the wounded, whether blue or butternut.”[9]

The dead and wounded littered the battlefield and the sights and smells were ghastly:

“Wherever men gazed, they saw dead bodies. A New Yorker thought they “lay as thick as the stones that is on father’s farm.” A stench smothered the field, moving John Geary to tell his wife, “My very clothes smell of death.” A Regular Army veteran exclaimed, “I have seen many a big battle, most of the big ones of the war, and I never saw the like.” [10] A resident of Gettysburg walked up to Little Round top and wrote of what she observed from the peak of that rocky hill:

“surrounded by the wrecks of battle, we gazed upon the valley of death beneath. The view there spread out before us was terrible to contemplate! It was an awful spectacle! Dead soldiers, bloated horses, shattered cannon and caissons, thousands of small arms. In fact everything belonging to army equipments was there in one confused and indescribable mass.” [11]

At Joseph Sherfy’s farm, scene of some of the heaviest fighting on the second day, his barn “which had been used as a field hospital, was left a burnt ruin, with “crisped and blackened limbs, heads and other portions of bodies” clearly visible.” [12] When the rains came, the wounded suffered terribly. Many of the field aid stations were set up next to the creeks that crisscrossed the battlefield, and those streams quickly flooded as torrents of rain water caused them to overflow their banks. “A New Jersey soldier watched in horror as the flood waters washed over and carried away badly wounded men unable to move to safety….” [13]

Oliver Howard took his escort to do a reconnaissance of the town on July 4th, one of the cavalry troopers described the scene:

“The battle field was the Awfulest sight I ever saw…The woods in front of our men the trees were riddled with Cannon ball and bullets evry limb shot off 20 feet high. Some say the Rebel dead lay six deep in the grave yard where we lay. Nearly every grave stone was shattered by shots and everything was torn to pieces. I went through the town on the 4th of July with the General. The streets were covered with dead. Every frame house were riddled with balls the brick ones dented thick where shot had hit.” [14]

Field hospitals were often little more than butcher shops where arms and legs were amputated by overworked surgeons and attendants while those with abdominal wounds that could not be easily repaired were made as comfortable as possible. Triage was simple. If a casualty was thought to have a reasonable chance at survival he was treated, if not they were set aside in little groups and allowed to die as peacefully as possible. Churches were requisition for use of the surgeons. A volunteer nurse noted: “Every pew was full; some sitting, some lying, some leaning on others. They cut off the legs and arms and threw them out the windows. Every morning the dead were laid on the platform in a sheet or blanket and carried away.” [15]

Chaplains were usually found with the doctors, caring for the physical as well as the spiritual needs of the wounded. Protestant chaplains might ensure that their soldiers “knew Jesus” and Catholics administered the Last Rites, often working together across denominational lines to care for their soldiers.

A Union chaplain described the ministry in the field hospitals and aid stations:

“Some of the surgeons were posted well up toward the front to give first aid. More of them were in the large field hospitals of division in more secure places at the rear. The chaplain might be at either place or at both by turns. Some made a point of watching for any wounded man who might be straggling back, who perhaps could be helped up into the saddle and ride back to the hospital. When the demand for help became urgent the chaplains were nurses. As the rows of wounded men grew longer, chaplains went from man to man to see what could be done to relieve their pain, perhaps to take a message or letter. All day into the night this work would continue. A drink of water, a loosened bandage on a swollen limb, a question answered, a surgeon summoned, a whispered word of comfort marked their course. Each night at sundown the men who died during the day were buried, with a short prayer, side by side in a common grave, each in his uniform with canvas wrapped around his face and a strip of paper giving his name and regiment in a bottle buttoned under his blouse.” [16]

The war would challenge the theology of the clergy who served as chaplains on both sides, as “individuals found themselves in a new and different moral universe, one in which unimaginable destruction had become a daily experience. Where could God belong in such a world? How could a benevolent deity countenance such cruelty and suffering? Doubt threatened to overpower faith….” [17] That sense of bewilderment is not lacking today among those of faith who return from war.

Some men, clergy and laity alike would attempt to find a theological meaning to the suffering. Many would do so in the theology of John Calvin which emphasized the Providence and foreknowledge of God. That theological frame of reference, of the results of battles and the death or wounding of men in war and the attendant suffering was found in the will, or providence of God was quite common among men of both sides who grew up during the Second Great Awakening, as it is today; and for some it was carried to fatalistic extremes. However, others like Colonel William Oates of the 15th Alabama, who considered himself a believing Christian, wrote that he believed God:

“endowed men with the power of acting for themselves and with responsibility for their acts. When we went to war it was a matter of business, of difference of opinion among men about their temporal affairs. God had nothing to do with it. He never diverted a bullet from one man, or caused it to hit another, nor directed who should fall or who should escape, nor how the battle should terminate. If I believed in such intervention of Providence I would be a fatalist….”[18]

The carnage around the battlefield was horrifying to most observers. Corporal Horatio Chapman of the 20th Connecticut Volunteers wrote about the sight on Cemetery Ridge on the night of July 3rd following the repulse of Pickett’s Charge:

But in front of our breastworks, where the confederates were massed in large numbers, the sight was truly awful and appalling. The shells from our batteries had told with fearful and terrible effect upon them and the dead in some places were piled upon each other, and the groans and moans of the wounded were truly saddening to hear. Some were just alive and gasping, but unconscious. Others were mortally wounded and were conscious of the fact that they could not live long; and there were others wounded, how bad they could not tell, whether mortal or otherwise, and so it was they would linger on some longer and some for a shorter time-without the sight or consolation of wife, mother, sister or friend. I saw a letter sticking out of the breast pocket of one of the confederate dead, a young man apparently about twenty-four. Curiosity prompted me to read it. It was from his young wife away down in the state of Louisiana. She was hoping and longing that this cruel war would end and he could come home, and she says, “Our little boy gets into my lap and says, `Now, Mama, I will give you a kiss for Papa.’ But oh how I wish you could come home and kiss me for yourself.” But this is only one in a thousand. But such is war and we are getting used to it and can look on scenes of war, carnage and suffering with but very little feeling and without a shudder.” [19]

Colonel William Oates of the 15th Alabama whose brave troopers assaulted Little Round Top on July 2nd wrote:

“My dead and wounded were nearly as great in number as those still on duty. They literally covered the ground. The blood stood in puddles in some places on the rocks; the ground was soaked with the blood of as brave men as ever fell on the red field of battle.” [20]

Another Confederate soldier described the scene west of the town on July 4th:

“The sights and smells that assailed us were simply indescribable-corpses swollen to twice their size, asunder with the pressure of gases and vapors…The odors were nauseating, and so deadly that in a short time we all sickened and were lying with our mouths close to the ground, most of us vomiting profusely.” [21]

The burial of the dead was too much for the soldier’s alone to accomplish. “Civilians joined the burial of the dead out of both sympathy and necessity. Fifty Confederates lay on George Rose’s fields; seventy-nine North Carolinians had fallen on a perfect line on John Forney’s farm.” [22]

Those tending the wounded recalled how many of the wounded selflessly asked medical personnel to tend others more badly wounded than themselves; a volunteer nurse wrote her sister: “More Christian fortitude was never witnessed than they exhibit, always say-‘Help my neighbor first, he is worse.’” [23] The Confederate wounded were the lowest priority for the badly overwhelmed Union surgeons and Lee had not done much to help, leaving just a few surgeons and attendants to care for the Confederates left on the battlefield. The Confederate wounded housed in the classrooms of Pennsylvania College were left in dire straits:

“All the rooms, halls and hallways were occupied with the poor deluded sons of the South,” and “the moans prayers, and shrieks of the wounded and dying were everywhere.” Between 500 and 700 wounded Confederates were jammed in with “five of our surgeons” and “no nurses, no medicines no kinds of food proper for men in our condition….” [24]

Across the battlefield the wounded were being treated in a variety of makeshift aid stations and field hospitals:

“Sergeant Major David E. Johnson of the Seventh Virginia was taken to the Myers house after the bombardment, suffering from a shrapnel wound to his left side and arm. “The shed in which I was placed,” he recalled, “was filled with the wounded and dying….I spoke to no one, and no one to me, never closed my eyes to sleep; the surgeons close by being engaged in removing the limbs of those nearby to be amputated….I heard nothing but the cries of the wounded and the groans of the dying, the agonies of General Kemper, who lay nearby, frequently being heard.” [25]

The suffering was not confined to the hospitals; John Imboden commanding the cavalry brigade protecting the Confederate wounded being transported home and supply trains described the horror of that movement:

“Scarcely one in a hundred had received adequate surgical aid, owning to the demands on the hard working surgeons from still far worse cases tat had to be left behind. Many of the wounded in the wagons had been without food for thirty-six hours. Their torn and bloody clothing, matted and hardened, was rasping the tender, inflamed, and still oozing wounds….From nearly every wagon as the teams trotted on, urged by whip and shout came such cries and shrieks as these:

“My God! Why can’t I die?” “My God! Will no one have mercy and kill me?” “Stop! Oh! For God’s sake stop for just one minute; take me out and leave me ton die on the roadside.” “I am dying! I am dying! My poor wife, my dear children, what will become of you?” [26]

Eventually, by July 22nd with most of the wounded evacuated a proper general hospital was set up east of the town and the remaining wounded taken there. That hospital, named Camp Letterman grew into “a hundred –acre village of cots and tents, with its own morgue and cemetery, and served more than 3,000 wounded before it was finally closed in November.” [27]

As for the families of the dead, many never found out the details of their loved one’s deaths, which caused their losses to be “in some sense unreal and thus “unrealized,” as the bereaved described them, recognizing the inhibition of mourning that such uncertainty imposed.” [28] Much was because of how overwhelmed the field hospital staffs were, and how inadequate their records of treatment and the dispositions of bodies were sketchy at best. “Reports from field hospitals were riddled with errors and omissions, often lacked dates, and were frequently illegible, “written with the faintest lead pencil.” [29]

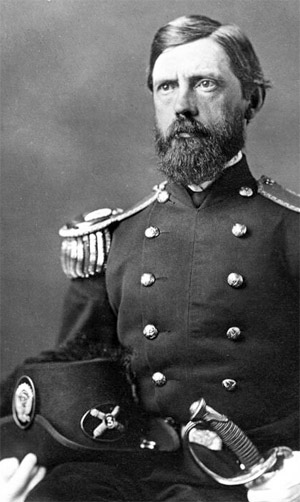

the killed and wounded were the great and the small. John Reynolds who died on day one, Winfield Scott Hancock, the valiant commander of the Union II Corps was severely wounded during Pickett’s Charge. Dan Sickles, the commander of Third Corps who had nearly brought disaster on the Federal lines by advancing to the Peach Orchard on July 2nd had his leg amputated after being grazed by a cannon ball at the Trostle Farm. Sickles, who survived the wound and the war, would visit the leg, which had carefully ordered his surgeons to preserve. The leg is now displayed at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington D.C.

The Army of the Potomac lost a large number of brigade and regimental commanders including Strong Vincent, the young and gallant brigade commander who helped save Little Round Top; George Willard who brought redemption to his Harper’s Ferry brigade on Cemetery Ridge stopping Barksdale’s charge on July 2nd; Colonel Augustus Van Horne Ellis who before being killed at Devil’s Den told his staff “the men must see us today;” and the young Elon Farnsworth, who had been promoted from Captain to Brigadier General just days before his death in a senseless ordered by his division commander Judson “Kill Cavalry” Kilpatrick, against Hood and McLaws dug in divisions as the battle ended.

The Confederates suffered grievous losses. Divisional commanders like Dorsey Pender and Johnston Pettigrew were mortally wounded, John Bell Hood was severely wounded, Isaac Trimble, wounded and captured while Harry Heth was wounded. Casualties were even higher for commanders and the brigade and regiment level, the list included excellent commanders such as Paul Semmes and William Barksdale, while Wade Hampton, Stuart’s best brigade commander was seriously wounded and would be out of action for months. The toll of brigade and regimental commanders who were killed or wounded was fearful. “At the regimental level approximately 150 colonels, lieutenant colonels and majors had been killed, wounded or captured. Of that number nineteen colonels had been slain, the most in any single battle in which the army had been engaged. Captains now led regiments.”[30]

In Picket’s division alone all three brigade commanders, Kemper, Armistead and Garnett were killed or wounded while twenty-six of forty Field Grade officers were casualties. Forty-six percent (78 of 171) of the regiments of the Army of Northern Virginia suffered casualties at the command level. The Confederate casualties, especially among the best leaders were irreplaceable and Lee’s Army never recovered from the loss of seasoned leaders who were already in short supply.

For some like Private Wesley Culp of the 2nd Virginia it was a final trip home. Culp had grown up in Gettysburg and had taken a job in Virginia prior to the war. In 1861 he enlisted to serve among his friends and neighbors. He was killed on the morning of July 3rd on Culp’s Hill on the very property owned by his uncle where he grew up and had learned to hunt.

One witness, Frank Haskell looked in at a field hospital in the Union II Corps area and wrote:

“The Surgeons with coats off and sleeves rolled up…are about their work,… “and their faces and clothes are spattered with blood; and though they look weary and tired, their work goes systematically and steadily on- how much and how long they have worked, the piles of legs, arms, feet, hands, fingers…partially tell.” [31]

All told between 46,000 and 51,000 Americans were killed or wounded during the three days of Gettysburg. Busey and Martin’s Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg list the following casualty figures, other accounts list higher numbers, some as many as 53,000. One also has to remember that many of the missing soldiers were killed in action, but their bodies were simply never found.

Killed wounded missing total

Union 3,155 14,531 5,369 23,055

Confederate 4,708 12,693 5,830 23,231

Total 7,863 27,224 11,199 46,286

To provide a reference point we need to remember that in 8 years of war in Iraq the United States suffered fewer casualties than during the three days of Gettysburg. It was the bloodiest single battle in American history, and it was a battle between brothers not against foreign enemies. To put it another perspective, even at the lowest estimates that the Army of Northern Virginia suffered more casualties that the U.S. losses in Iraq and Afghanistan combined. Robert E Lee testified to Congress following the war “the war… was an unnecessary condition of affairs, and might have been avoided if forbearance and wisdom had been practiced on both sides.” [33] Lee’s “Old Warhorse” James Longstreet asked “Why do men fight who were born to be brothers?” [34]

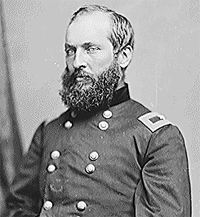

James Longstreet

Of the two Longstreet was certainly most honest. Lee made a false equivalence between the years of Southern attempts to negate the rights of Free States and to expand slavery. The North was patient, even when the Souther states began to secede the were not calls for war but reconciliation. Longstreet would go on, be reconciled and make himself persona non grata in much of the South for fighting for Reconstruction, and openly stating that slavery was the root cause of the war, he grieved the loss of so many friends who he had served with on both sides before the war. Lee on the other hand didn’t even attend the funeral of Stonewall Jackson, and was harsh toward his critics as well as towards those he believed had failed him.

The carnage and death witnessed by survivors of Gettysburg and the other battles of the war changed Civil War soldiers as much as war has before or after. James Garfield, who served as a general in the Union army and went on to become President of the United States noted: “at the sight of these dead men whom other men killed, something went out of him, the habit of a lifetime, that never came back again: the sense of the sacredness of life and the impossibility of destroying it.” [35]

Others, like veterans of today had trouble adjusting to life after the war. “Civil War veterans had trouble finding employment and were accused of being drug addicts. Our word “hobo” supposedly comes from homeless Civil War veterans- called “hoe boys” – who roamed the lanes of rural America with hoes on their shoulders, looking for work.” [36] Following the war, during the turmoil of Reconstruction and the massive social change brought about by the industrialization of society and rise of “industrial feudalism” numerous veterans organizations were founded, for those that belonged to them they were “one of the principle refuges for old soldiers who had fought for a very different world than the one they found around them.” The Grand Army of the Republic was the most prominent of these organizations. “In more than 7,000 GAR posts across the United States, former soldiers could immerse themselves in a bath of sentimental memory; there, they established a ritualized camp geography, rekindled devotion to emancipation and preached the glories of manly independence.” [37]

At the end of the war, Joshua Chamberlain, the hero of Little Round Top who was well acquainted with the carnage of war suffered immensely. His wounds never healed fully, and he struggled to climb out of “an emotional abyss” in the years after the war. Part was caused by his wounds which included wounds to his sexual organs, shattering his sexuality and caused his marriage to deteriorate. He wrote his wife about the “widening gulf between them, one created at least in part by his physical limitations: “There is not much left in me to love. I feel that all too well.” [38]

Gouverneur Warren, who had helped save the Union at Little Round Top wrote to his wife while on Engineering duty after the war: He wrote in 1866 “Indeed the past year…was one of great despondency for me…I somehow don’t wonder that persons often remark how seldom I laugh, but it is really seldom that I do.” He wrote again in 1867 “I wish I did not dream that much. They make me sometimes dread to go to sleep. Scenes from the war, are so constantly recalled, with bitter feelings I wish to never experience again. Lies, vanity, treachery, and carnage.” [39]

The killing at Gettysburg and so many other battles “produced transformations that were not readily reversible; the living into the dead, most obviously, but the survivors into different men as well, men required to deny, to numb basic human feelings at costs they may have paid for decades after the war ended, as we know twentieth and twenty-first-century soldiers from Vietnam to Iraq continue to do; men who like James Garfield, were never quite the same again after seeing fields of slaughtered bodies destroyed by me just like themselves.” [40]

When one walks through the Gettysburg Soldier’s Cemetery one finds that the graves are arrayed in a fan shape, with designated areas for the dead from each loyal state that had soldiers at Gettysburg. They are placed without regard to rank as an acknowledgment of their equality. Those that could be identified are marked, while hundreds of others are marked as unknown. When I look at those that are marked ”unknown” I realize that all were sons, husbands, fathers, nephews, and friends of others. Their families never had closure.

Joshua Chamberlain asked the most difficult questions when viewing the devastation around Petersburg in the final days of the war:

“…men made in the image of God, marred by the hand of man, and must we say in the name of God? And where is the reckoning for such things? And who is answerable? One might almost shrink from the sound of his own voice, which had launched into the palpitating air words of order–do we call it?–fraught with such ruin. Was it God’s command that we heard, or His forgiveness that we must forever implore?” [41]

I do believe with all my heart that Chamberlain’s questions should always be in our minds as we send young men and women to war, of any kind or for any reason.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

Notes

[1] Faust, Drew Gilpin, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War Vintage Books, a division of Random House, New York 2008 p.41

[2] Grossman, Dave On Killing: The Psychological Costs of Learning to Kill in War and Society. Back Bay Books, Little, Brown and Company New York 1995, 1996 p.92

[3] Sager, Guy The Forgotten Soldier originally published as Le Soldat Oublie Editions Robert Laffont 1967, Translation Harper and Row Inc 1971, Brasey’s Washington D.C 2000 p.223

[4] Bismarck, Otto von Speech, August 1867

[5] Clausewitz, Carl von. On War Indexed edition, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976 p.89

[6] Wittenberg, Eric J, Petruzzi, David and Nugent, Michael F. One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia July 4-14 1863 Savas Beatie LLC New York NY and El Dorado Hills CA 2008,2001 p.27

[7] Ibid. Wittenberg One Continuous Fight p.28

[8] Sears, Stephen W Gettysburg Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.508

[9] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.510

[10] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.303

[11] Schultz, Duane The Most Glorious Fourth: Vicksburg and Gettysburg July 4th 1863. W.W. Norton and Company New York and London, 2002 p.357

[12] Faust This Republic of Suffering p.81

[13] Ibid. Wittenberg One Continuous Fight p.30

[14] Ibid. Wittenberg One Continuous Fight pp.32-33

[15] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg. p.508

[16] Brinsfield, John W. et. al. Editor, Faith in the Fight: Civil War Chaplains Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg PA 2003 pp.121-122

[17] Ibid. Faust. This Republic of Suffering p.267

[18] Oates, Willam C. and Haskell, Frank A. Gettysburg: The Confederate and Union Views of the Most Decisive Battle of the War in One Volume Bantam Books edition, New York 1992, originally published in 1905 p.138

[19] Chapman, Horatio Civil War Diary of a Forty-niner pp.22-24 Retrieved from http://www.dbappdev.com/vpp/ct20/hdc/HDC630703.htm 8 April 2014

[20] Oates, William C. Southern Historical Papers, April 6th, 1878 retrieved from http://www.brotherswar.com/Civil_War_Quotes_4h.htm 18 July 2014

[21] _________ What Happened to Gettysburg’s Confederate Dead? The Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park, retrieved from http://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2012/07/26/what-happened-to-gettysburgs-confederate-dead/ 18 July 2014

[22] Ibid. Faust. This Republic of Suffering p.81

[23] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.333

[24] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.469

[25] Brown, Kent Masterson Retreat from Gettysburg: Lee, Logistics and the Gettysburg Campaign University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 2005 p.56

[26] Imboden, John D. The Confederate Retreat from Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts. Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ p.424

[27] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.469-470

[28] Ibid. Faust. This Republic of Suffering p.267

[29] Ibid. Faust. This Republic of Suffering p.113

[30] Wert, Jeffry D. A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2011 Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.444

[31] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Company Boston, New York 2004 p.466

[33] Flood, Charles Bracelen, Lee: The Last Years Houghton Books, New York 1981 p.124

[34] Longstreet, James in New York Times, July 24, 1885, retrieved from the Longstreet Society http://www.longstreetsociety.org/Longstreet_Quotes.html18 July 2014

[35] Ibid. Faust. This Republic of Suffering p.55

[36] Shay, Jonathan Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming Scribner, New York and London 2002 p.155

[37] Guelzo Allen C. Fateful Lightening: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2012 p.523

[38] Longacre, Edward Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the ManCombined Publishing Conshohocken PA 1999 p.259

[39] Jordan, David M. Happiness is Not My Companion: The Life of G.K. Warren Indiana University Press, Bloomington Indiana 2001 pp.248-249

[40] Ibid. Faust. This Republic of Suffering p.60

[41] Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence, The Passing of the Armies: An Account of the Final Campaign of the Army of the Potomac, Based on the Personal Reminisces of the Fifth Corps G.P Putnam’s Son’s 1915, Bantam Books, New York 1993 Amazon Kindle Edition p.41