Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

I am pre-posting a number of articles to run this Independence Day weekend so I can work on the article that I place on posting July 4th. These are articles from my Gettysburg text that deal with events of July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd 1863 during the Battle of Gettysburg. They have all appeared on this site before in different forms, but the Battle of Gettysburg still matters, what was done there on the behalf of freedom cannot be allowed to be forgotten. .

Have a great weekend.

Peace

Padre Steve+

Doubleday Takes Command

As the initial Confederate attacks were driven back by the actions of Reynolds, Doubleday and their subordinate commanders, Harry Heth’s battered brigades fell back and regrouped to prepare for another assault. As Heth reorganized his division he was bolstered by the arrival Major General Dorsey Pender’s Division powerful division.

With John Reynolds dead and Oliver Howard moving his Eleventh Corps into position on Cemetery Hill and to the north of Gettysburg, Major General Abner Doubleday had assumed command of First Corps on McPherson and Seminary Ridge and successfully parried Heth’s initial attacks, in the process shattering the brigades of James Archer and Joseph Davis.

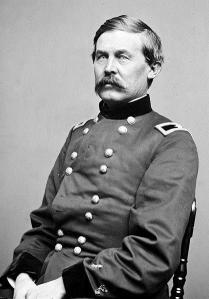

Major General Abner Doubleday, United States Army

Doubleday was an experienced soldier but did not enjoy a stellar reputation in the Army of the Potomac, despite the fact that he was the senior division commander in First Corps. Doubleday came from a prominent New York family; his grandfather had fought in the American Revolution and had fought at Bunker Hill. His father served four years in Congress. By the time he was admitted to West Point Doubleday had worked for two years as a civil engineer. Doubleday graduated 24th in a class of 52 in the West Point Class of 1842 along with future Gettysburg commanders “Longstreet, McLaws, Richard Anderson and John Newton.” [1] After his graduation he served a rather uneventful career as an artillery officer, including service in Mexico and on the frontier. Shortly before the war he was transferred to South Carolina where he was second in command at Fort Sumter when the Confederates opened fire on the fort and began the Civil War.

Doubleday was definitely an unusual character by the standards of the ante-bellum army officer corps. The “mustachioed, barrel-chested Doubleday considered himself a thoroughly modern man, unencumbered by the cheap affections of honor and chivalry with which so many officers bedecked themselves.” [2] He had few real friends in the army. He was a rather vocal abolitionist “which endeared him to few of the army’s socially conservative generals” [3] and he allowed his political opinions to infringe on his relationships with other officers. In the days before the war at Fort Sumter “he relished being hissed in the streets as a “Black Republican” when his official duties took him over the water to downtown Charleston.” [4]

Doubleday fired the first shot on the Union side at Fort Sumter, and with the expansion of the army to meet the rebellion he “expected that his anti-slavery credentials would guarantee a rise to the top of Lincoln’s army.” [5] However, he was to be disappointed. While promotion came to him it was not to the top of the army. Doubleday had the “reputation of being a cautious, deliberate plodder,” [6] and the artillery commander of First Corps, the somewhat curmudgeonly but honest, Colonel Charles Wainwright noted “Doubleday knows enough, but he is entirely impractical, and so slow at getting an idea through his head.” [7] Likewise, the new army commander George Meade had formed an unfavorable opinion of Doubleday’s leadership ability, when both served as division commanders in First Corps. Meade considered Doubleday “slow and pedantic.” [8]

Doubleday was somewhat portly and his physical appearance did little to inspire his soldiers or officers, and some of his troops nicknamed him “Old Forty-Eight Hours” for his deliberate, even slothful style.” [9] His promotion in the wartime army was rather typical for a career officer. He was “promoted to Brigadier General in February 1862 and commanded a brigade at Second Bull Run and a division at South Mountain and in later battles.” [10] As a brigade commander his best work was at Brawner’s Farm on the eve of Second Manassas, where Doubleday on his own initiative threw “two of his regiments into line to bolster Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s brigade against a larger Confederate force…together the fought a superior force to a standstill.” [11] He was promoted to Major General in November 1862 and received command of the First Division Third Division of First Corps. At Antietam Doubleday led the division “into the carnage of the Cornfield and West Woods, and one colonel described him as a “gallant officer…remarkable cool and at the very front of battle.” [12] He led the division again at Fredericksburg, but the division saw little action. After the reorganization of the army following Fredericksburg he was given command of Third Division of First Corps at Chancellorsville, but again saw no action.

At Gettysburg Doubleday went into battle “stiff and pompous, still wearing his laurels as an “old Sumter hero” [13] and complaining about the Henry Slocum to command Twelfth Corps, even though he was senior to Slocum. That being said, Doubleday’s actions in the wake of Reynolds’s death demonstrated that he was capable of quick thinking and leadership from the front and in the next few hours Doubleday “had his best command hours of the war.” [14]

A Brief Lull

After the initial repulse of the Heth’s division, Doubleday continued to organize his defenses. He could see Heth’s division reforming its lines on Herr’s Ridge and Pender’s division as it arrived and deployed to Heth’s left. Doubleday had no directions from Reynolds as to that General’s defensive plan but be believed was that the ridges could be a redoubt and his instinct was “to hold on to the position until ordered to leave it,” an officer of the 149th Pennsylvania heard Doubleday say that “all he could do was fight until he got sufficient information to form his own plan.” [15] Doubleday wrote in his after action report, “to fall back without orders from the commanding general might have inflicted lasting disgrace upon the corps, and as general Reynolds, who was high in the confidence of General Meade, had formed his lines to resist the entrance of the enemy into Gettysburg, I naturally supposed that it was the intention to defend the place.” [16] Wadsworth’s division, bloodied but unbeaten remained in place in McPherson’s woods and across the Cashtown Road where Cutler’s brigade had fought the Confederates to a standstill at the Railroad Cut. During the lull these brigades had their ammunition replenished by his recently arrived ammunition trains.

To counter the Confederate move to his right he deployed his own small Third Division under the acting command of Brigadier General Thomas Rowley. He placed Rowley’s brigade to the left of the Iron Brigade to extend the line to the south and the brigade of Colonel Roy Stone to occupy the area around the McPherson House and Barn which had been left open when Cutler’s brigade advanced to the railroad cut.

When the Second Division under the command of Brigadier General John Cleveland Robinson arrived Doubleday placed it in reserve around the Lutheran Seminary where they and some of John Buford’s dismounted troopers began to set up a hasty “barricade of fence rails and fieldstone on the seminary’s west side.” [17] Doubleday and Wadsworth deployed every artillery piece of that the Corps had available to support their infantry, sometimes over the objections of the Corps artillery commander Colonel Charles Wainwright. Wainwright “had no confidence in Doubleday, and felt that he would be a weak reed to lean upon,” [18] and on his own initiative deployed most of his batteries on Seminary Ridge where he believed that they could affect the battle but not be torn to pieces by Confederate artillery or shredded by close range musket fire. Despite the “pleas from infantry officers along the rise, Wainwright would send guns forward only under peremptory orders to do so.” [19] Wainwright was hesitant to risk his guns in exposed positions along McPherson’s Ridge and deployed most of his available artillery near the seminary in good defensive positions and stationed his limbers not far off so in the event of a retreat that he might have the opportunity to save his guns.

About Two o’clock Major General Oliver Howard, commander of the Eleventh Corps who was now the senior officer on the field made his way to seminary ridge where he met with Doubleday. Howard had already been working to support First Corps by ordering Schurz, who was now in acting command of Eleventh Corps to move north of the town to connect with Doubleday’s flank and securing Cemetery Hill as a natural redoubt and fallback position. While little is known what was said between the two commanders it is certain that Howard notified Doubleday of the locations of his corps headquarters and that of his divisions. Howard asked Doubleday “to continue his work of protecting the left of the Union position, while he would take care of the right…..Before leaving, Howard, repeated the instructions he had given Wadsworth, to hold the position as long as he could and then retire.” [20] Doubleday asked Howard for reinforcements, but there were none available, the best that either man could hope was that Henry Slocum’s Twelfth Corps, now about five miles distant could arrive soon. “If Slocum could make Gettysburg in the next hour and a half, Howard could post the 12th Corps on the right flank of his own corps and firm up the defensive arc that now stretched north and west of Gettysburg.” [21] However, despite the repeated requests of Howard, Slocum never came and did not advance toward Gettysburg until about three-thirty in the afternoon. Howard’s aid Captain Daniel Hall who delivered the messages and briefed Slocum on the situation at Gettysburg later stated that Slocum’s “conduct on that occasion was anything but honorable, soldierly, or patriotic.” [22]

With his troops under heavy artillery fire and Heth and Pender’s divisions advancing, a new threat emerged from the north. Messengers from Gamble’s cavalry scouts of Buford’s division to the north of town reported the arrival of Ewell’s Second Corps. To meet the threat Doubleday was obliged to send Robinson’s division north to occupy the extension of Seminary Ridge known as Oak Ridge. His lead brigade was under the command of Brigadier General Henry Baxter, and it advanced to the end of the ridge near the Mummasburg Road where it was joined by Brigadier General Gabriel Paul’s brigade.

Unlike the relatively small brigades of Third Division whose command structures were disrupted by Reynold’s death and Doubleday’s acting command of the corps, these brigades were comparatively large and powerful units and very well led. Their commander, Robinson “an old regular whose flowing beard lent him the look of a biblical prophet, had seen considerable fighting but was yet to be tested as a division commander.” [23] During this battle he more than met the test of an effective division commander. As the advance regiments of the division moved into position on Oak Ridge and the Mummasburg road they were greeted by a few of Gamble’s cavalrymen who told them “You stand alone between the Rebel army and your homes. Fight like hell!” [24] Upon their arrival Robinson refused the line in order to connect to the advance elements of Eleventh Corps which were arriving to the north of Gettysburg.

Enter Second Corps

On June 30th Rodes’ division marched about twenty miles and bivouacked at Heidlersburg where he met with his corps commander Ewell, fellow division commander Jubal Early and Isaac Trimble who was accompanying Second Corps where they puzzled over Lee’s orders as to the movement of Second Corps the following day, which indicated that Ewell should march to Gettysburg or Cashtown “as circumstances may dictate.” [25] Neither Rodes nor Early gave favorable opinions of the order and Ewell asked the rhetorical question “Why can’t a commanding General have someone on his staff who can write an intelligible order?” [26]

Ewell assumed that Cashtown was the desired junction of the army ordered his to march from on the morning of July 1st 1863 toward Cashtown to join with Hill’s corps. His choice of routes was good as it gave him the opportunity to turn south towards Gettysburg “as circumstances” dictated in compliance with Lee’s rather vague order of the day before.[27]

Rodes’s division was at Middletown (modern Biglerville) when Ewell received A.P. Hill’s message that he was moving on Gettysburg between eight and nine in the morning. Ewell immediately directed Rodes onto the “Middletown-Gettysburg road and instructed Early to march directly toward Gettysburg on the Heidlersburg road.” [28] As he did so he sent a note to Lee informing him of the situation and about noon he received Lee’s response that Lee “did not want a general engagement brought on till the rest of the army came up.” [29] But by the time Ewell received that instruction events were beginning to spiral out of control on his front just as they had on Harry Heth front just a few hours before.

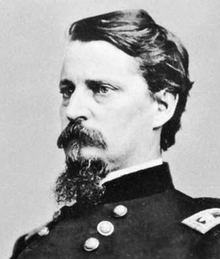

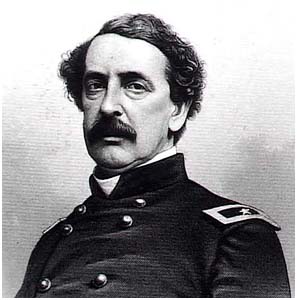

Major General Robert Rodes, C.S.A.

Although Ewell was closer to Rodes than Hill was to Heth at the beginning of the battle, Rodes like Heth was also operating somewhat independently as Ewell “preferred to ride near the tail of his column in his buggy.” [30] Like Heth when confronted with the opportunity for battle, he ignored the instruction “to avoid a general engagement, if practicable.” [31] The operation was Rodes’ first as a Major General and he like his fellow division commanders, Jubal Early and Allegheny Johnston, the young and aggressive Rodes was operating independently “as Ewell preferred” until the corps was reunited in the evening. [32] During the early part of the march to Gettysburg he had performed well but July 1st 1863 “would never be remembered as a great day for Robert Rodes.” [33] As he moved his division south he, like Ewell was unaware that a battle was developing to their front and both were surprised when they heard the sound of artillery about four miles north of the town. Rodes later wrote that “to my surprise, the presence of the enemy there in force was announced by the sound of a sharp cannonade, and instant preparations for battle were made.” [34]

Rodes deployed his infantry brigades and “posted Lt.Col. Thomas H. Carter’s battalion of artillery along the nose of the ridge, where it opened with “fine effect” on the Union line stretched across McPherson’s Ridge.” [35] As Rodes set about deploying his troops for his assault on Oak Ridge, Ewell could see Robinson’s division moving up to Oak Ridge and the Mummasburg road facing his troops. He also observed the advance of the two divisions of Eleventh Corps which Carl Schurz was moving into position north of the town. Seeing the developments to his front and right Ewell considered Lee’s order obsolete and noted that “it was already too late to avoid an engagement without abandoning the position already taken up…and I determined to push the attack vigorously.” [36] Likewise he sent an aide to contact Jubal Early and enjoin that General to move to battle.

Rodes’s Division and His Commanders

Robert Rodes was new to commanding a division. The big, blond and charismatic Rodes was one of the most popular leaders in the Army of Northern Virginia. Rodes had a great ability to inspire his subordinates. This was in large part due to his handsome physical appearance which made him look “as if he had stepped from the pages of Beowulf” [37] but also due to his “bluff personality featuring “blunt speech” and a tincture of “blarney.” [38]

Rodes graduated at the age of 19 from the Virginia Military Institute and remained at the school as an assistant professor for three years. He left VMI when Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson received the full professorship he desired and became a successful civil engineer working with railroads in Alabama. He had just been appointed a full professor at VMI as the war was declared. [39]

His career had been remarkable. Rodes was “tough, disciplined and courageous; he was one of those unusual soldiers who quickly grew into each new assignment.” [40] In just two years he had “risen from captaining a company of “Warrior Guards” in Alabama in 1861 to earning the equivalent of a battlefield promotion to major general for the fight he made at Chancellorsville.” [41] As a brigadier he had shown remarkable leadership on the battlefield and off, taking care of the needs of his soldiers and worked to have “at least one company per regiment to drill on a field gun and to keep up that training from time to time, so that his men could service a cannon in a crisis.” [42]

With the coming of war Rodes abandoned his academic endeavors returned to his recent home of Alabama where he was appointed Colonel of the 5th Alabama regiment of infantry. Early in the war Rodes distinguished himself as the commander of that regiment and later as brigade commander of Ewell’s former brigade, a promotion that Ewell recommended. His brigade was one of the spearheads of Jackson’s attack on Eleventh Corps at Chancellorsville, where he “was a brilliant presence on the field, exhorting his men with mustache flying. Jackson personally congratulated him on his gallant performance.” [43] He took acting command of Major General D. H. Hill’s former division during that battle and handled that unit well. Following Chancellorsville, Rodes was recommended for promotion to Major General and permanent command the division by Stonewall Jackson. The act was one of Jackson’s last acts before his untimely death from pneumonia while recovering from his wounds sustained at Chancellorsville. With his appointment Rodes became the first non-West Point graduate to command a division in the Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Rodes’s division was the largest in the army with five brigades and approximately 8,000 soldiers present at Gettysburg, almost as many as the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac. His brigade commanders were a mixed bag, ranging from the excellent to the incompetent. Among the former he had George Doles, Stephen Ramseur and Junius Daniel. However, Rodes was saddled with two commanders of dubious quality, Brigadier General Alfred Iverson, who was hated by his men and Colonel Edward O’Neal, a leading secessionist politician “who had absolutely no military experience before the war” [44] and who had been ineffective as an acting brigade commander when he took over for Rodes at Chancellorsville. However, Lee was forced to leave O’Neal at the head of his brigade for lack of other senior leaders over Rodes’ objections. It would be a mistake that would come to haunt him.

However, Rodes was fortunate to have Brigadier Generals Stephen Ramseur and George Doles in command of two of his brigades. Both had led their units well at Chancellorsville under Rodes direction, and would fight well in Gettysburg and subsequent actions. [45] Brigadier General Junius Daniel, though an experienced West Point graduate with a solid record was new to the Army of Northern Virginia, unfamiliar with his commander, while and his brigade was untested in combat.

Brigadier General George Doles commanded a brigade. Doles was not a professional soldier but a former Georgia militia where he commanded a company, “the Baldwin Blues,” one of the oldest and best-trained military units in the state.” [46] As a Colonel he “had shown fiber and vigor” [47] as commander of the 4th Georgia regiment which he commanded at South Mountain and Antietam. Doles was promoted to Brigadier General after Antietam, and commanded the brigade at Chancellorsville. At Chancellorsville his brigade was part of Jackson’s attack against the Federal XI Corps and in the thick the action throughout the battle. Doles was noted for his leadership and valor. By Gettysburg he had a reputation for “being among the Southern army’s most daring, hard fighting brigadiers.” [48]

Stephen Ramseur was the youngest General in the Army of Northern Virginia, he had graduated from West Point in 1861, immediately resigned to join the Confederate cause and within seven months he would be a Brigadier General. He was elected captain of the Ellis Light Artillery of Raleigh North Carolina, and became colonel of the 49th Alabama in 1862. He led the regiment “with distinction during the Seven Days.” [49] While leading his troops at Malvern Hill he was severely wounded. Ramseur was noted for “being a fighter and for his skill in handling troops in battle.” [50]

The young Colonel was promoted to Brigadier General in November 1862 following the Battle of Antietam. He led a North Carolina brigade with great daring at Chancellorsville where he was wounded in the shin by a shell fragment. Along with his division commander Robert Rodes, the still injured Ramseur was “one of the brightest lights in Lee’s army as it approached the field at Gettysburg.” [51]

Junius Daniel was an 1851 graduate of West Point who served seven years before resigning to run his family plantation in 1858. When war came he Daniel volunteered for service and was appointed commander of the 14th North Carolina. He had much brigade command time but little combat experience, as his brigade had been posted in North Carolina and the Virginia Tidewater, thus, not sharing in the Army of Northern Virginia’s year of glory and slaughter. “Daniel’s brigade joined Rodes division in Virginia as a result of the army’s reorganization after Chancellorsville and in time for it to take part in the invasion of Pennsylvania.” [52] Despite his lack of combat experience Junius Daniel was well respected and “had the essential qualities of a true soldier and successful officer, brave, vigilant, honest…gifted as an organizer and disciplinarian, skilled in handling troops.” [53] At Gettysburg he “proved himself a valiant soldier and capable leader….” [54]

This left Rodes with two brigades under questionable leadership, and both would cause him immense grief on the morning of July 1st 1863.

One North Carolina brigade was commanded by Brigadier General Alfred Iverson. Iverson who was considered a “reliable secession enthusiast” was appointed to command the North Carolina troops whose political steadiness and loyalty was questioned by Richmond. [55] Because of this Iverson became “embroiled in bitter turmoil with his North Carolinians.” [56] Iverson had served in the Mexican War and in the army of the 1850s. However, he owed his appointments in both the U.S. Army and that of the Confederacy to political patronage, his father being a prominent U.S. Senator.

Though Iverson was from Georgia he helped raise the 20th North Carolina regiment of infantry and became its first Colonel. However he was constantly at war with his officers and his regiment never bonded with him. As a regimental commander he did see a fair amount of action but his leadership was always a question mark. After he took command of the brigade Iverson “sent an aide to the camp of his former regiment to arrest all twenty-six of its officers.” [57] Those officers responded in kind and “retained a powerful bevy of counsel including…Colonel William Bynum who would later become a member of the Supreme Court.” [58] Iverson then refused promotions to any officer who had opposed him. One of the aggrieved officers of the 20th North Carolina “wrote an outraged letter home insisting that resistance to Iverson was every reasonable man’s duty and asserting that he would oppose him again “with great pleasure” if the occasion offered.” [59] In his previous action at Chancellorsville Iverson “had not distinguished himself.” [60] After Chancellorsville he had “been stigmatized for his conspicuous absence at the height of the fighting.” [61]

Rodes’s old brigade was in the worst hands all. Due to the lack of qualified officers it was commanded at Gettysburg by its senior regimental commander Colonel Edward A. O’Neal. O’Neal was another political animal, who unlike Iverson had no prior military training and nothing he had done before the war “had prepared him for command at any level.” [62] As an Alabama lawyer O’Neal was however well connected politically which gained him rapid rank and seniority over other officers, this eventually led to his command of the 26th Alabama which was a part of Rodes brigade. Rodes had reservations about O’Neal’s ability to command the brigade and recommended two other officers, John Gordon and John T. Morgan who instead were assigned to command other brigades. [63] The Confederate War Department in Richmond forwarded a commission to Lee for O’Neal to be promoted to Brigadier General before Gettysburg, but Lee, who had serious reservations about O’Neal’s capabilities blocked the promotion. [64]

The Confederate Disaster at Oak Ridge

The arrival of Rodes’s division as on the field in the van of the Confederate Second Corps was decisive in turning the tide of the battle toward the Confederates that afternoon. When Rodes arrived with Ewell, the Federal First Corps was facing west against Heth and Pender’s divisions and its line only extended about a quarter mile north of the Railroad Cut.

The Union First Corps and Buford’s cavalry division had fought Heth’s poorly coordinated and led attacks to a standstill, but when Rodes arrived he found “a golden opportunity spread before him.” [65] From his position at Oak Ridge he saw the opportunity to take the Federal troops opposing Hill in the flank though his position did not “provide him as comprehensive view as he thought.” [66] His desire was to advance south along Oak Ridge using it to screen his movements in order to execute an attack on the Federal right flank. But before he could do this “the First Corps Generals had made preparations to oppose him.” [67] Robinson’s two brigades under Baxter and Paul deployed and “hurried in line stone and wood fences approximately at right angles to Rodes proper line of advance.” [68] Rodes could see the deployment but the fences obscured the exact positions of Robinson’s troops from him. Seeing the advance of the First Corps units as well as the emergence of Schurz’s troops from Eleventh Corps advancing out of the town the aggressive Confederate commander decided to launch an immediate attack.

Carter’s artillery, which had deployed in the open and was had “opened an enfilading fire all along the line to the Fairfield road” [69] now drew the fire of Captain Hubert Dilger’s Battery I First Ohio Artillery from Howard’s XI Corps which had just arrived near Oak Ridge. Dilger commanded one of the best artillery units in the army. He was a German immigrant and professional artilleryman who had served in the Grand Duke of Baden’s Horse Artillery. He came to the United States at beginning of the war at the invitation of a distant uncle, to “practice the war-making he had only previously rehearsed.” [70] Dilger was “blunt and a bit arrogant…loved by his men but not by his superiors.” At Chancellorsville he and his battery had helped save the Federal right “when it used a leapfrogging technique to keep the victorious Confederate infantry at bay.” [71] At Gettysburg Dilger again displayed his talent.

Upon its arrival Dilger’s battery opened “a storm of counter-battery fire” [72] on Carter’s battalion as well as the infantry brigade of O’Neal which was near it. The effect of Dilger’s fire on Carter’s artillery disrupted its operation and was successful in blowing up several caissons and guns causing significant numbers of casualties among the men. [73] Seeing the carnage to one battery that he had not placed, Carter “accosted Rodes and asked, “General, what fool put that battery up yonder?” Only to realize after an “awkward pause and a queer expression on the face of all Rodes’ staffers that Rodes himself had placed it there.” [74] In response, the chastised division commander replied “You had better take it away, Carter.” [75] Throughout the rest of the engagement Dilger’s battery would make itself known, shattering Confederate infantry assaults and damaging Southern artillery batteries.

The young division commander was overconfident as he ordered the attack. Thinking he had an adequate grasp of the situation he did not order a reconnaissance before launching the attack, nor did the commanders of the brigades spearheading the attack put out skirmishers, the normal precaution when advancing in the face of the enemy. [76] Rodes deployed his troops over the rough ground of the ridge as quickly as he could and dashed off a note to Jubal Early stating “I can burst through the enemy in an hour.” [77] He was to be badly mistaken, and “like Heth in the south, he paid in disproportionate blood for the ready aggressiveness which in the past had been the hallmark of the army’s greatest victories, but now seemed mere rashness and the hallmark of defeat.” [78]

Rodes deployed George Doles’ excellent brigade to guard his left against the advancing Eleventh Corps units until Early’s division could arrive, something he expected momentarily. Doles and his brigade conducted this task admirably until the arrival of Jubal Early’s division, which enabled it to join the attack on Eleventh Corps divisions north of the town. Initially the movement of the brigade opened a potentially dangerous gap between Doles brigade and O’Neal’s brigade to its right, but this could not be exploited by the Federals. To hold this gap between Doles and O’Neal Rodes pulled one regiment, the 5th Alabama from O’Neal.

To make his main attack Rodes initially deployed his division on a one brigade front as they arrived on the battlefield in line-of-march. As the leading elements of the division neared the Federal positions Rodes, made what appeared to be a simple change of plan to “attack on a two brigade front, sending in O’Neal’s and Iverson’s men simultaneously, then following up with Daniel’s brigade in echelon on the right.” [79] Ramseur’s brigade was held in close reserve. In theory it was a sound plan, but everything is more complicated when bullets start flying. The execution of this change in plan was “bungled right at the start.” [80] None of “the three brigade commanders was sure what the signal for the advance would be” [81] and since Rodes had made no reconnaissance, and none of the brigades put out skirmishers the direction of the attack was faulty, units were mingled and a gap developed between O’Neal and Iverson. [82] The attack “though vigorous, was a disaster” [83] and the plan floundered due to the stout resistance of Robinson’s troops and the “nicely matched incompetence of O’Neal and Iverson” [84] neither of who advanced with their assaulting troops.

O’Neal’s brigade became disoriented and “went in with only three regiments and at an angle different from that indicated by Rodes. Instead of leading his troops in the attack O’Neal remained in the rear with the Fifth Alabama, a reserve regiment,” [85] the regiment Rodes had left behind to guard the gap between O’Neal and Doles’s brigades. The last regiment, the Third Alabama had been aligned on the flank of Doles’s brigade and since Rodes had moved it “evidently concluded…that it was no longer his to direct.” [86] When Rodes discovered this he had to send a staff officer to ensure that the regiment was properly attached to Daniel’s brigade. That regiment was thus left out of the initial advance. The attack stalled almost immediately when O’Neal’s three attacking regiments were fired upon by Union troops of Robinson’s division who had been hidden by a wall which had obscured them from Rodes’s view.

Striking O’Neal’s advancing troops at the oblique, Robinson’s battle hardened Union troops slaughtered the unsuspecting Confederates. Though they were outnumbered the Union men were solid veterans from Baxter’s brigade who were aided by Dilger’s artillery which delivered “effective canister fire at O’Neal’s brigade.” [87] The combined fire of Baxter’s troops as well as Dilger’s artillery “killed or wounded about half of the advancing men with a series of point blank volleys pumped directly into their flank.” [88] O’Neal’s decision to remain back with his reserve regiment rather than “going forward to direct the advancing regiments” [89] caused further problems because there was no officer on the spot to direct the action of the three regiments.

Rodes noted in his after action report that O’Neal’s three attacking regiments “moved with alacrity (but not in accordance with my orders as to direction)” and that when he ordered the 5th Alabama up to support “I found Colonel O’Neal, instead of personally superintending the movements of his brigade, had chosen to remain with his reserve regiment. The result was that the whole brigade was repulsed quickly and with loss….” [90] As O’Neal’s troops fell back in confusion they exposed Iverson’s brigades flank to the Federal fire.

As Rodes’s continued bad luck would have it, Iverson, like O’Neal on his right did not advance simultaneously with O’Neal or on the same axis, but instead waited to see O’Neal’s advance. [91] When it advanced, the brigade “about 1,450 strong, kept on under artillery fire through the open field “as evenly as if on parade.” Then its alignment became faulty, and without Iverson on hand to correct it, the brigade with strange fatality began to bear left toward the stone wall…” [92] As a result the brigade drifted right it’s exposed left was subject to attack from Baxter’s and Paul’s brigades of Robinson’s division still hidden behind the stone wall.

When the Confederates got within fifty yards of Baxter’s troops they were overwhelmed by a fierce resistance from the concealed Federal troops. The commander of the 83rd New York, the Swiss born lieutenant Colonel Joseph A. Moesch, shouted: “Up men, and fire.” Moesch rode behind his line cheering his men on, but they needed no urging. In the words of one of one, “The men are no longer human, they are demons; a curse from the living here, a moan from the dying there. ‘Give them —- shouts one.’ See them run’ roars another.” [93] The well concealed veterans of Baxter regiments slaughtered them as they had O’Neal’s men just minutes before. “One regiment went down in such a neat row that when its survivors waves shirt tails, or any piece of cloth remotely white, Iverson thought that the whole regiment of live men were surrendering.” [94] As the Confederate attack collapsed some “of the regiments in Robinson’s division changed front again, charged, and captured nearly all the men who were left unhurt in three of Iverson’s regiments.” [95] Official Confederate reports list only 308 missing but that number differs from the Union reports, Robinson reporting 1000 prisoners and three flags and Baxter’s brigade nearly 400. [96] As Robinson’s troops smashed the brigades of O’Neal and Iverson, they were joined by the remnants of Cutler’s brigade which changed its face from west to north to deliver more devastating fire into the Confederates.

Iverson was badly shaken by the slaughter and “went to pieces and became unfit for further command,” [97] after being just close enough to the action to observe it. He panicked and notified Rodes that one of his regiments had surrendered in masse though Iverson later retracted that in claim in his official report where he noted “when I found afterward that 500 of my men were left lying dead and wounded on a line as straight as a dress parade, I exonerated …the survivors.” [98] His brigade had lost over two-thirds of its strength in those few minutes, one regiment the 23rd North Carolina lost 89 percent of those it took into battle, and at the end of the day would “count but 34 men in its ranks.” [99] Iverson’s conduct during the battle was highly criticized by fellow officers after it. Accused of cowardice, drunkenness and hiding during the action he was relieved of his command upon the army’s return to Virginia “for misconduct at Gettysburg” [100] and sent back to Georgia. Some complained after the war that Iverson was helped by politicians once he returned to Richmond and instead of facing trial “got off scot free & and had brigade of reserves given to him in Georgia.” [101]

With the center of his attacking forces crushed the brigades of Junius Daniels and Stephen Ramseur entered the fray to the right of Iverson’s smashed brigade. These capable officers achieved a link up with the battered brigades of Harry Heth at the Railroad cut after Daniel’s brigade had fought a fierce battle with Culter’s and Stone’s brigades in the area [102] and allowed the Confederates of A.P. Hill and Dick Ewell’s Corps to form a unified front from which they were able to resume their attack in even greater numbers against the battered remnants of First Corps.

To the east Doles’s brigade advanced with Jubal Early’s division smashed the outnumbered and badly spread out divisions of Oliver Howard’s Eleventh Corps. The timely arrival of that division coupled with the skillful work of Daniel and Ramseur saved Rodes from even more misfortune on that first day of battle, but Rodes’ plan “to burst through the enemy” with his division had evaporated. [103] By the end of the day his division had lost nearly 3000 of the 8000 that it had begun the afternoon.

The battle at Oak Ridge was a series of tactical debacles within a day of what appeared to be a “Confederate strategic bonanza.” [104] Despite the mistakes Rodes never lost his own self-control. He recovered from each mistake and continued to lead his division. He “kept his men on the ridge driving forward until with Hill, and on the flats left joined Early’s right to form a continuous line into Gettysburg.” [105] It was a hard lesson for the young Major General, but one that he learned from. Rodes continued to serve with distinction as a division commander would be killed in action while leading a counterattack by his division against Philip Sheridan’s army at the Third Battle of Winchester on September 19th 1864.

Abner Doubleday’s Best Performance and Disgraceful Treatment

On the other hand Abner Doubleday proved himself as a capable commander who was able to provide effective leadership during a crisis situation. Although he is one of the most underappreciated Union commanders at Gettysburg he “ably rose to the occasion, as did divisional commanders James Wadsworth and John Robinson.” [106] Though his abilities were suspect, especially by George Meade and Colonel Wainwright, the Corps artillery commander Doubleday managed to hold off superior Confederate forces, and even inflicted a significant defeat on the divisions of Harry Heth and Robert Rodes. During the fighting against ever increasing numbers of Confederates, First Corps inflicted massive casualties on their opponents. “Seven of the ten Southern brigades incurred casualties from 35 to 50 percent, and the total for all brigades came to an estimated 6,300 officers and men, or about 40 percent of their strength.” [107] Doubleday’s troops held on long enough to support the left flank of Eleventh Corps as it was being assaulted by Early’s division.

When Winfield Scott Hancock arrived on Meade’s behest to take command at Gettysburg Oliver Howard informed him that First Corps “had given way at first contact” [108] implicitly blaming Doubleday for the collapse of the Federal line. Hancock delivered the report in a note to Meade which said “Howard says that Doubleday’s command gave way” [109] This false report fixed in Meade’s mind that his doubts about Doubleday’s ability were correct. To Doubleday’s amazement Meade then cancelled his order appointing Doubleday to command First Corps and ordered John Newton, a division commander, far junior to Doubleday in Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps to replace Doubleday. A badly disappointed Doubleday resumed command of his division. In large part Meade’s appointment of Newton over Doubleday was also political. Doubleday’s fellow abolitionist division commander in First Corps, James Wadsworth said that “Meade’s “animosity” toward Doubleday rested in a “past political difference.” [110] Doubleday, the abolitionist Republican was not acceptable to Meade, the conservative Unionist Democrat and ally of Gorge McClellan. The fact that Newton “was not regarded as daring or brilliant” [111] and was regarded by many as a “pet” of Meade, did not matter. Meade’s volcanic temper and temptation to allow politics to cloud his military judgement meant that “Newton was the only other major general he could trust politically.” [112] When Doubleday formally protested to Meade he was dismissed from Army of the Potomac.

He left the Army of the Potomac never held a field command during the war, however, he was brevetted in the Regular Army to both brigadier and major general. Doubleday served in administrative capacities in Washington D.C. until the end of the war and testified against Meade during the politically charged hearings of the Committee on the conduct of the War. Doubleday remained bitter toward Meade and he “was never reconciled to Meade’s relieving him as acting commander of First Corps in Favor of Maj. Gene. John Newton, who was his junior in rank and the reproach that it implied.” [113] After the war Doubled reverted to his rank as a Colonel in the Regular Army and was made Colonel of the 35th U.S. Infantry in San Francisco. From 1871 until his retirement in 1873 Doubleday commanded the African American “Buffalo Soldier” 24th Infantry Regiment in Texas. He died in New York on January 25th 1893, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Among the members of the honor guard at his funeral in New York was a man named Abraham Mills who would play a major role in Doubleday’s future fame.

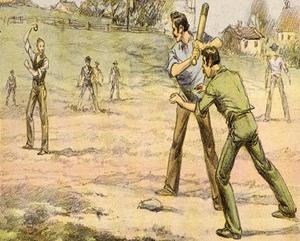

A Myth and Legend Greater than Gettysburg: Abner Doubleday and Baseball

Interestingly enough Doubleday, who was unappreciated as a general became linked forever to the game known as America’s national pastime and to Cooperstown New York, the home of Baseball’s Hall of Fame. As such he is probably better known to most Americans, particularly baseball fans than any Union general who fought at Gettysburg.

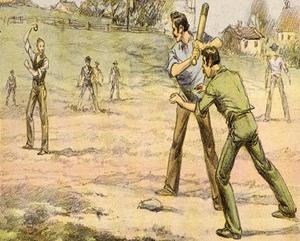

Like the Civil War, Baseball too is filled with myths which connect it to our culture, and one “is the myth that Abner Doubleday invented the sport one fine day in 1839 at the farmer Phinney’s pasture at Cooperstown.” [114] It was early American baseball star Albert G. Spaulding who linked the creation of baseball to the Civil War and in particular to Abner Doubleday by way of an apocryphal story of one of Doubleday’s childhood friends, years after Doubleday’s death. In 1907, Spaulding worked with Abraham G. Mills the fourth President of the National League, the same man who had served in Doubleday’s funeral honor guard to conclude that “that the first scheme for playing it, according to the best evidence obtained to date, was devised at Cooperstown New York, in 1839.” [115] But this is simply myth and the underappreciated hero of the first day of battle at Gettysburg is much better known for something that he did not do.

The ironies of history and myth are fascinating. Interestingly Mills paid homage to Doubleday noting, “in the years to come, in the view of hundreds of thousands of people who are devoted to baseball, Abner Doubleday’s fame will rest evenly, if not quite so much that he was its inventor…as upon his brilliant and distinguished career as an officer in the Federal Army.” [116]

Notes

[1] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p.121

[2] Goodheart, Adam 1861: The Civil War Awakening Vintage Books a division of Random House, New York 2011 p.5

[3] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.276

[4] Ibid. Goodheart 1861 p.5

[5] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.30

[6] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.181

[7] Wainwright, Charles S. A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright 1861-1865 edited by Allan Nevins, Da Capo Press, New York 1998 p.172

[8] Cleaves, Freeman Meade of Gettysburg University of Oklahoma Press, Norman and London 1960 p.143

[9] Tagg, Larry The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle Da Capo Press Cambridge MA 1998 Amazon Kindle Edition p.25

[10] Ibid. Pfanz Harry Gettysburg: The First Day p.122

[11] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.26

[12] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.26

[13] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.273

[14] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.181

[15] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.161

[16] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.206

[17] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.162

[18] Ibid. Wainwright A Diary of Battle p.233

[19] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.200

[20] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.282

[21] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.162

[22] Melton, Brian C. Sherman’s Forgotten General: Henry W. Slocum University of Missouri Press, Columbia and London 2007 p.121

[23] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.34

[24] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.206

[25] Ibid Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.148

[26] Ibid Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.149

[27] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.160

[28] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command p.281

[29] Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg: A.P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell in a Difficult Debut in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.49

[30] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.472

[31] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.564

[32] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Twop.472

[33] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.138

[34] Luvaas, Jay and Nelson Harold W editors. The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg South Mountain Press, Carlisle PA 1986 p.35

[35] Pfanz, Donald. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier’s Life University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 1998 p.305 Pfanz credits Ewell for this but nearly every other source lists Rodes as having placed Carter’s artillery battalion on Oak Hill.

[36] Ibid. Pfanz, Donald Richard S. Ewell p.305

[37] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.39

[38] Krick, Robert K. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day of Gettysburg in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.115

[39] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.123

[40] Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse The Free Press, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2008 p.243

[41] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg p.53

[42] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.244

[43] Gwynne, Samuel C. Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson Scribner, a Division of Simon and Schuster New York 2014 p.537

[44] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.299

[45] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.117

[46] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.287

[47] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.386

[48] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.288

[49] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.251

[50] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001

[51] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.290

[52] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.179

[53] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.292

[54] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.21

[55] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.25

[56] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.53

[57] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.129

[58] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.131

[59] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.130-131

[60] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.564

[61] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.145

[62] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.120

[63] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.123

[64] Ibid. Pfanz Harry Gettysburg: The First Day p.162 Also see Krick pp.123-124 Following Gettysburg Lee continued to block O’Neal’s promotion and that officer went to extraordinary lengths to obtain a General’s commission using every political ally he had in Alabama and in Richmond. Finally Lee settled the matter before the Wilderness campaign writing that he made “more particular inquiries into his capacity to command the brigade and I cannot recommend him to the command.” Krick pp.123-124

[65] Ibid. Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.472

[66] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[67] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.286

[68] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.119

[69] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.286

[70] Ibid Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.208

[71] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 pp.59-60 Dilger was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Chancellorsville in 1893, part of the citation stating that Dilger: “fought his guns until the enemy were upon him, then with one gun hauled in the road by hand he formed the rear guard and kept the enemy at bay by the rapidity of his fire and was the last man in the retreat.”

[72] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.118

[73] Ibid Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.210

[74] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[75] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.61

[76] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[77] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[78] Ibid. Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.473

[79] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.197

[80] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.197

[81] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[82] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.565

[83] Ibid. Pfanz, Donald Richard S. Ewell p.305

[84] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.120

[85] Ibid. Pfanz, Donald Richard S. Ewell p.305

[86] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.124

[87] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.198

[88] Ibid. Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.473

[89] Ibid Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.565

[90] Ibid Luvaas The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg p.36

[91] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.132

[92] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.289

[93] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.172

[94] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.134

[95] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.290

[96] Ibid Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.175

[97] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command p.290

[98] Ibid Luvaas The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg p.37

[99] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.201

[100] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.173

[101] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.136

[102] Ibid. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.292

[103] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.173

[104] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.138

[105] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.138

[106] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.245

[107] Ibid. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.307

[108] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.294

[109] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.224

[110] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.294

[111] Ibid. Cleaves Meade of Gettysburg p.143

[112] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.224

[113] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.355

[114] Will, George F Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball Harper Collins Publishers, New York 1990 p.294

[115] Kirsch, George B. Baseball in Blue and Gray: The National Pastime in the Civil War Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 2003 p.xiii

[116] Ibid.. Kirsch Baseball in Blue and Gray p.xii