Friends of Padre Steve’s World

This is another part of my Gettysburg text Chapter on John Reynolds. I have divided it up into three sections. The first was the biographic section, the second, published yesterday was about Kate Hewitt, the girl he left behind. Today is an expanded version of what was the original chapter which focused almost exclusively on Reynolds’s and his actions at Gettysburg on the morning of July 1st 1863.

I hope that you enjoy.

Peace

Padre Steve+

On the night of June 30th Reynolds was awash in reports, some of them conflicting and even though he was without Meade’s course of action for the next day “concluded that Lee’s army was close by and in force.” [1] He spent the night at his headquarters “studying the military situation with Howard and keeping in touch with army headquarters.” [2] Howard noted Reynolds anxiety and “received the impression that Reynolds was depressed.” [3] After Howard’s departure Reynolds took the opportunity to get a few hours of fitful sleep before arising again at 4 a.m. on July 1st.

When morning came, Reynolds was awakened by his aide Major William Riddle with Meade’s order to “advance the First and Eleventh Corps to Gettysburg.” [4] Reynolds studied the order and though he expected no battle that morning, expecting “only moving up to be in supporting distance to Buford” [5] took the prudent and reasonable precautions that his Confederate opponents A.P. Hill and Harry Heth refused to take as they prepared to move on Gettysburg.

His troops were in fine spirits that morning even though it had been busy. After a breakfast of hardtack, pork and coffee the troops moved out. An officer of the Iron Brigade noted that the soldiers of that brigade were “all in the highest spirits” while Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Dawes of the “placed the fifes and drums at the head of the Sixth Wisconsin and ordered the colors unfurled” as the proud veterans marched forward into the sound of the raging battle to the tune of “The Campbell’s are Coming.” [6]

Though Reynolds was not expecting a fight he organized his march in a manner that ensured if one did happen that he was fully prepared. The precautionary measures that he took were those that any prudent commander having knowledge that strong enemy forces were nearby would take. Reynolds certainly took to heart the words of Napoleon who said “A General should say to himself many times a day: If the hostile army were to make its appearance in front, on my right, or on my left, what should I do?” [7]

This was a question that A.P. Hill and Harry Heth seemed not to consider on that warm and muggy July morning when Heth was committing Lee’s army to battle on his own authority. Reynolds was also about to commit the Army of the Potomac to battle, but unlike Heth who had no authority to do so, Reynolds “had at least been delegated the authority for making such a decision” [8] by his army commander George Meade. Though Meade was unaware of what was transpiring in the hills beyond Gettysburg he implicitly trusted the judgement of Reynolds, and Meade been with the advanced elements of Reynold’s wing he too “probably would have endorsed any decision he made.” [9]

Reynolds placed himself with the lead division, that of Wadsworth, and “directed Doubleday to bring up the other divisions and guns of the First Corps and had ordered Howard’s Eleventh Corps up from Emmitsburg.” [10] Reynold’s also understood the urgency of the situation and “wanted all the fighting troops to be up front, so he instructed Howard not to intermingle his supply wagons with his infantry. Similar instructions had been given to Abner Doubleday; to ensure that the First Corps wagons would wait until the Eleventh Corps foot soldiers had passed.” [11]

Instead operating in the normal fashion of rotating units on the march, Reynolds opted to save time. Since Wadsworth’s First Division was further advanced than his other First Corps divisions, Reynolds instructed it to move out first with Cutler’s brigade in the lead followed by the Iron Brigade under Brigadier General Solomon Meredith. In doing so Reynolds countermanded the order of the acting corps commander Doubleday who had ordered Wadsworth’s division to allow the other divisions of First Corps to pass his before advancing. Reynolds told Wadsworth that Doubleday’s order “was a mistake and that I should move on directly.” [12]

He went forward with Wadsworth’s division and gave Doubleday his orders for the coming engagement. Doubleday later recalled that when Reynolds arrived to discuss the situation that Reynolds:

“read to me the various dispatches he had received from Meade and Buford, and told me that he should go at once forward with the leading division – that of Wadsworth – to aid the cavalry. He then instructed me to draw in my pickets, assemble the artillery and the remainder of the corps and join him as soon as possible. Having given me these orders, he rode off at the head of the column, and I never saw him again.” [13]

Reynolds ordered Howard’s Eleventh Corps to follow First Corps and according to Doubleday directed an aid of Howard to have Howard “bring his corps forward at once and form them on Cemetery Hill as a reserve.” [14] Howard received the order and since his troops were ready to move out “no time was lost in setting them in motion.” [15] While some writers believe that Reynolds directed Oliver Howard to prepare Cemetery Hill as a fallback position [16] there is more evidence that points to Howard selecting the that commanding hill himself. [17] Regardless of which is correct the result was that both Reynolds and Howard recognized the importance of the position and took action to secure it.

Likewise Reynolds ordered Sickles’ III Corps to come up from Emmitsburg where that corps had bivouacked the previous night. [18] Sickles had heard the guns in the distance that morning and sent his senior aide, Major Henry Tremain to find Reynolds. Reynolds told Tremain “Tell General Sickles I think he had better come up” but the order left Sickles in a quandary. He recalled “he spend an anxious hour deciding what to do” [19] for he had “been ordered by Meade to hold his position at Emmitsburg” [20] and Sickles sent another rider to Reynolds and awaited the response of his wing commander instead of immediately advancing to battle on 1 July and it would not be until after 3 P.M. that he would send his lead division to Gettysburg.

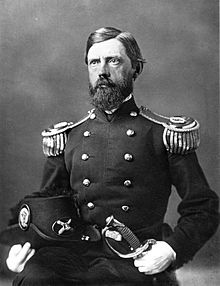

According to Doubleday Reynolds’s intention was “to fight the enemy as soon as I could meet him.” [21] Reynolds rode forward with some of his staff into the town as the infantry of the First Corps and the Eleventh Corps moved advanced. As they rode through the town Reynolds and his party were met by “a fleeing, badly frightened civilian, who gasped out the news that the cavalry was in a fight.” [22] When he came to the Lutheran Seminary he came across Buford. It was a defining moment of the Civil War, a moment that shaped the battle to come. It has been recounted many times and immortalized on screen in the movie Gettysburg, a time “when the entire battle would come down to a matter of minutes getting one place to another.” [23]

As the rough and tumble Kentuckian, Buford, and Reynolds, the dashing Pennsylvanian, discussed the situation they had to know that odd that they were facing. With close to 32,000 rebels from the four divisions of Hill’s and Ewell’s corps closing in from the west and the north and with only about 18,000 men of First Corps, Eleventh Corps and Buford’s cavalry division to meet them, the odds were not in his favor, but unlike other battles that the army of the Potomac faced, this time the army and its commanders were determined not to lose the battle and not to retreat and for the first time John Reynolds “led the advance” and for the first time in the war “might have some say about fighting.” [24]

Reynolds and Buford committed their eighteen thousand men against Lee’s thirty-two thousand in a meeting engagement that develop into a battle that would decide the outcome of Lee’s invasion. Likewise it was a battle for the very existence of the Union. Abner Doubleday noted the incontestable and eternal significance of the encounter to which Buford and Reynolds were committing the Army of the Potomac on July 1st 1863:

“The two armies about to contest on the perilous ridges of Gettysburg the possession of the Northern States, and the ultimate triumph of freedom or slavery….” [25]

Even though they understood that they were outmanned and outgunned by the advancing Confederates, both Buford and Reynolds knew that this was where the battle must be waged. It was here on this spot, for the ground gave them an advantage that they would not have elsewhere; but only if they could hold on long enough for the rest of the army to arrive. As Alan Nolan wrote: “this Pennsylvania ground – was defensible, and behind it, through the town, loomed Cemetery Hill, another natural point of defense if the battle at Seminary Ridge went against the Federals.” [26]

Reynolds vs. Heth July 1st

When John Buford saw Reynolds infantry advancing as the Confederates increased the pressure on his outnumbered cavalry, he remarked to a staff member “now we can hold this place.” [27] Buford was not mistaken, when Reynolds rode up to the scene of the battle on Seminary Ridge he greeted Buford, who was in the cupola of the seminary. He called out “What’s the matter John?” to which Buford replied “The devil’s to pay” before he came down to discuss the tactical situation with Reynolds. [28] Buford explained the situation noting that “I have come upon some regiments of infantry…they are in the woods…and I am unable to dislodge them.” [29]

Reynolds needed no other convincing. He asked Buford if he could hold and quickly sent off a number of messages. One officer wrote: “The Genl ordered Genl Buford to hold the enemy in check as long as possible, to keep them from getting into town and at the same time sent orders to Genl Sickles…& Genl Howard to come as fast as possible.” [30] Additionally, Reynolds sent a message to Meade stating: “The enemy are advancing in strong force. I fear they will get to the heights beyond the own before I can. I will fight them inch by inch, and if driven into the town, I will barricade the streets and hold them back as long as possible.” [31] He directed Major Weld of his staff to take it to Meade with all haste as Weld recalled: “with the greatest speed I could, no matter if I killed my horse.” [32] When Meade received the report he was concerned, but with great confidence in Reynolds’s ability he remarked “Good!…That is just like Reynolds; he will hold on to the bitter end.” [33]

After dictating his instructions and sending off his messengers, Reynolds then did what no senior Confederate commander did during the entirety of the battle, he rode back and took personal charge of the movements of his troops to hurry them forward. Unlike Heth who so badly misjudged the tactical situation, he had taken note of the ground and recognized from Buford’s reports that “the Confederates were marching only on that single road and thus would not be able to push their forces to the front any faster than Reynolds could reach the battlefield with his First Corps divisions.” [34] It was a key observation on his part which again allowed him to make appropriate decisions as to how he shaped the battle.

Reynolds leadership at this point might be considered reckless by the standards of our day when senior commanders control battles from miles away with the help of real time intelligence and reporting, including live video feeds, or even the standards of the Second World War. But then in the Civil War a commander in combat could only really control the actions of troops that he could see and because of the time that it took to get messages to subordinate commanders, and the real possibility that verbal orders could be badly misinterpreted in the heat of battle.

Reynolds exercised command directing infantry formations into battle and assisting his artillery battery commanders in the placement of their guns. This was far different than the way that most senior Confederate leaders, including Lee, Longstreet, Hill and Ewell directed their units during the battle of Gettysburg. But such action such action was in keeping with Reynolds’s character, especially in the defense of his home state. Reynolds’ philosophy of command regarding volunteer troops was that they “were better led than driven” [35] and as such he led from the front and Abner Doubleday noted that Reynolds was “inflamed by at seeing the devastation of his native state, was most desirous of getting at the enemy as soon as possible.” [36]

“For God’s Sake Forward!” McPherson’s Ridge

John Reynolds recognized that time was of the essence if his forces were to hold the ground west of the town selected a shortcut around the town for First Corps. Those forces were directed across the fields near the Condori farm toward the back side of Seminary Ridge, with Reynolds’ staff helping to remove fences to speed the advance. [37] It was not an easy advance as the troops had to move across the farm fields at an oblique and have to “double-quick for a mile and a quarter in the thick humidity just to reach the seminary.” [38] One member of the corps recalled “I never saw men more willing to fight than they were at Gettysburg.” [39]

Recognizing that “after two full hours of fighting, Buford’s troopers” fighting on McPherson’s Ridge, were “at the limits of their endurance,” Reynolds ordered Wadsworth’s brigades “to bolster the cavalry and oppose the rebel infantry coming at them.” [40]

As troops arrived Reynolds directed them into position. He directed the artillery of Captain James Hall’s 2nd Maine Battery to McPherson’s Ridge instructing Hall “I desire you to damage their artillery to the greatest possible extent, and to keep their fire from our infantry until they are deployed….” [41]

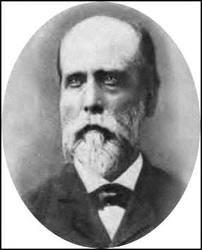

The leading infantry of First Corps was Major General James Wadsworth’s understrength division containing just two brigades, just over 3000 soldiers, its losses from Chancellorsville not being made good and as the result of the loss of regiments discharged because their enlistments had expired. [42] Wadsworth was not a professional soldier, but like many generals on both sides was a political general who despite his lack of military experience was a natural leader of men. Wadsworth was “a vigorous white-haired old man who had been a well-to-do gentleman farmer in New York State before the war” [43] and he “had interrupted his service in the war to run for and lose his state’s governorship the preceding fall.” [44] He ran against the anti-war, anti-administration and frequently pro-Southern Copperhead Horatio Seymour, but he did not leave the army in order return to the state to mount a personal campaign “on the ground that it did not befit a soldier.” [45]

“What the gray haired general lacked in experience and skill, he compensated with a fighting spirit.” [46] Oliver Howard of Eleventh Corps said that Wadsworth was “always generous and a natural soldier” [47] and while Wadsworth was no professional but he performed admirably on July 1st 1863. Wadsworth was beloved by his men because he demonstrated true concern and care for their living conditions and training and on that morning Wadsworth was commanding his division leading it into action with “an old Revolutionary War saber in his hand.” [48] The gallant Wadsworth would be mortally wounded ten months later leading a division of Gouverneur Warren’s Fifth Corps in the opening engagements of the Wilderness. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles noted in his diary when Wadsworth died that Wadsworth “should, by right and fair-dealing, have been at this moment Governor of New York…No purer or single-minded patriot than Wadsworth has shown himself in this war. He left home and comforts and wealth to fight the battles of the Union.” [49]

With their gallant commander at their head the division may not have had much in force in the way of numbers, but the units of the division were “good ones,” composed of hardened combat veterans that went into battle with an eye to victory. In the van was Brigadier General Zylander Cutler’s brigade of New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians, the “celebrated Bucktails.” [50] When they were mustered into service the soldiers of the 13th Pennsylvania had adopted a “bucktail” attached to their service caps as a distinctive insignia, a practice that spread to other regiments of the brigade and for which the brigade became known throughout the army.

Cutler had spent much of his early life in Maine working in a number of fields and businesses. He made a fortune several times and lost it, first when his mill burned down, but he rebuilt his businesses and diversified and “as a leading businessman, Cutler was elected to the Maine senate, college trusteeships and a railroad directorship, but he was financially ruined by the panic of 1866 and moved to Milwaukee to start his career over again.” [51] The tough-minded Cutler had some previous military experience fighting Indians as a member of the Maine militia and was made Colonel of the 6th Wisconsin. Cutler was described by one of his soldiers as “being as “rugged as a wolf” and was “a tenacious fighter, a trait that endeared him to the tough-minded Gibbon.” [52] After Antietam Gibbon recommended Cutler for promotion to Brigadier General and command of the Iron Brigade, but Cutler had been wounded at the bloody Battle of Brawner’s Farm and Solomon Meredith gained a promotion and command of that celebrated brigade. However, in on November 29th 1862 having recuperated from his wounds Cutler was promoted to brigadier general and received command of his Bucktails in March of 1863. The brigade saw only minor action at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg would be the fierce brigadier’s first chance since being wounded to command in combat.

This fine brigade was followed by Brigadier General Solomon Meredith’s “Iron Brigade” composed of westerners in their distinctive black “Jefferson Davis” or “Hardie” hats. The brigade had been initially commanded by Major General John Gibbon, now commanding a division in Winfield Scott Hancock’s Second Corps. Gibbon turned the brigade into one of the finest in the army. At the Battle of Turner’s Gap on South Mountain during the Antietam campaign, the brigade earned its name.

After that bloody battle George McClellan exclaimed “They must be made of Iron!” and Hooker replied, “By the Eternal, they are iron! If you had seen them at Bull Run as I did, you would know them to be iron.” [53] In the fierce battle at South Mountain the brigade had lost over a quarter of its strength, but had gained a share of immortality among the ranks of the United States Army. “The Western soldiers immediately seized on this as their title, and the reputation of the brigade and its new name were soon broadcast around Federal campfires.” [54] The regiments of the brigade rivalled many Regular Army units in effectiveness and discipline and “the black hats became their trademark.” [55] Often committed to the fiercest battles the brigade had been decimated, but now along with the Bucktails it advanced up down Seminary Ridge and up the back side of McPherson’s Ridge. A member of an artillery battery who saw the Bucktails and the Iron Brigade advance recalled:

“No one…will ever again see those two brigades of Wadsworth’s Division – Cutler’s and the Iron Brigade – file by as they did that morning. The little creek made a depression in the road, with a gentle ascent on either side, so that from our point of view the column, as it came down the slope and up the other, had the effect of huge blue billows of men topped with a spray of shining steel, and the whole spectacle was calculated to give nerve to a man who never had one before.” [56]

Reynolds directed Cutler’s Bucktails to proceed north of the Cashtown Pike and then “called the Iron Brigade into action on the south side” [57] leading the hearty Westerners himself. Reynolds directed then Wadsworth to take change of the action on the north side of the road while he looked after the left. [58] When Reynolds made that decision he made another. He ordered the 6th Wisconsin of the Iron Brigade into reserve, leaving the Iron Brigade a regiment short but giving him the advantage of having a ready reserve which “permitted them to take full advantage of their interior lines, shift their strength about, and apply it where most needed.” [59]

At about 10:30 the 2nd Wisconsin advanced into the woods Reynolds urged them forward: “Forward men, for God’s sake and drive those fellows out of those woods….” [60] As he looked around toward the seminary to see the progress of reinforcements, Reynolds was struck in the back of the neck by a bullet and fell dead. “Had it come a short time earlier, Reynolds’s death might have thrown the I Corps into fatal confusion.” [61] But Doubleday, who command now fell was up to the task on that sultry July morning.

Cutler’s brigade moved north and engaged Davis’ men near the railroad cut. Here the Cutler’s line was “hardly formed when it was struck by Davis’s Confederate brigade on its front and right flank.” [62] His troops were heavily outnumbered by the advancing Confederates and Davis’ troops initially had the upper hand. In a savage fight they inflicted massive casualties on Cutler’s regiments which outnumbered and being flanked were ordered to withdraw by Wadsworth in order to save them, with the exception of one regiment, the 147th New York nicknamed the Ploughboys which “did not get the order” [63] and though isolated held its ground, “with the support of a fresh six-gun battery whose gunners simply refused to quit.” [64] This was the 2nd Maine Battery under the command of Captain James Hall. Though caught in a cross fire of Rebel artillery and assailed by skirmishers Hall’s artillerymen gamely continued the fight withdrawing by sections, “fighting a close canister range and suffering severely.” [65] The New Yorkers and Hall’s battery battled the Mississippians and the “Ploughboys fell “like autumn leaves; the air was full of lead.” [66]

The inexperienced Davis and his green troops were buoyed by this “gratifying local success” [67] and attempted to exploit it. At this point the Confederates were fatigued by the long march and the fighting and the troops of the 2nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina “were all jumbled together without regiment or company.” [68] Davis attempted to use the unfinished railroad cut “as cover for getting on the enemy’s flank without exposure.” [69] It was a decision that Davis lived to regret. As his troops his units crowed into it, the two regiments of Cutler’s brigade south of the turnpike, the 14th Brooklyn and the 95th New York turned to meet them and were joined by the reserve regiment of the Iron Brigade, the 6nd Wisconsin under Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Dawes. Dawes ordered an immediate advance and called out to Major Edward Pye of the 95th “Let’s go for them Major.” The 6th Wisconsin and the New Yorkers took the Confederates in the flank with enfilade fire, “it was like shooting fish in a barrel.” [70] Dawes’ men slaughtered many of those unfortunate soldiers, and the battle soon became a hand to hand struggle as North Carolinians and Mississippians struggled with the Wisconsin men and New Yorkers.

The melee in and around the cut did not last long:

“for the Confederates were unable to resist their attackers….From the brow of the cut Dawes shouted down to the Confederates below him: “Where is the colonel of this regiment?” A Confederate field officer heard him and replied, “Who are you?” Dawes answered, “I command this regiment. Surrender or I will fire.” [71] Dawes’s men took over 200 prisoners, [72] and the battle flag of the 2nd Mississippi. [73]

The charge had last but minutes yet had shattered Joe Davis’s brigade. Davis was wholly unprepared for this reverse and signaled his forces to pull back convinced that “a heavy force was…moving rapidly to our right.” [74] However, the cost to the 6th Wisconsin was great, “Dawes estimated that 160 men of the 6th fell, not including the brigade guard, whose casualties he did not know.” [75]

Brigadier General Solomon Meredith’s Iron Brigade, which had been brought forward by Doubleday hit Archer’s brigade in the front in the woods on McPherson’s Ridge. Meredith was an unmarried North Carolina Quaker who had moved to Indiana in 1840 owning little more than the clothes that he was wearing. He became a farmer but found politics more to his liking and was elected as a county sheriff and to the state legislature. When the war came he was serving as the Clerk of Wayne County. Meredith, like so many volunteer officers on both sides owed much of his advancement in the army to his political connections. In Meredith’s case this was to Meredith’s friend Governor Oliver Morton. Critics of Meredith decried his appointment as Colonel of the 19th Indiana as “a damnable swindle.” [76] Yet Meredith commanded the regiment effectively and received command of the brigade in November 1862. John Gibbon, the regular officer who initially commanded the brigade was critical of Meredith’s appointment but the soldiers appreciated their kind, six-foot seven-inch tall commander who they affectionately knew as “Long Sol.” But despite the carping of his political enemies and the opposition of Gibbon, Meredith like so many others like him who, “extroverted and ambitious by nature, accustomed to asserting themselves, these men did the best that they could, for themselves and their responsibilities, and they somehow sufficed” [77] though they had no formal military training or experience.

As the Iron Brigade advanced toward McPherson’s Ridge and engaged the enemy, Doubleday “urged the men…to hold it all hazards.” Doubleday later wrote that the troops of the brigade, “full of enthusiasm and the memory of their past achievements they said to me proudly, “If we can’t hold it, where will you find men who can?” [78]

Animated by the leadership of Reynolds and now Doubleday they “rushed to the charge, struck successive heavy blows, outflanked and turned the enemy’s right, captured General Archer and a large portion of his brigade, and pursued the remainder across Willoughby Run.” [79] The effect was dramatic as the Iron Brigade overwhelmed Archer’s brigade, whose soldiers now realized they were facing “the first team.” Members of the Iron Brigade recalling the voices of Confederate soldiers exclaiming “Here are those damned black-hat fellers again…’Taint no militia-that’s the Army of the Potomac.” [80] As they attempted to withdraw they piled up at a fence near Willoughby Run and were hit in the flank by “a Michigan regiment that had worked its way around through the woods to the south.” [81] Archer’s Confederates were unable to resist the assault of the Iron Brigade, “Some fled; others threw down their arms and trembling asked where they should go, while others simply dropped their rifles and ducked through the Union formations to the Union rear.” [82]

As for their commander, Archer the ignominy only got worse. “A muscular Irish private in the 2nd Wisconsin ran forward and seized General Archer bodily and made a prisoner of him.” [83] Coddington wrote: “It was a bad moment for the Army of Northern Virginia, and Archer gained the unenviable distinction of being the first of its general officers to be captured after Lee took command.” [84] Doubleday, who knew Archer from the old army, wrote of meeting Archer after that very angry general after had been taken prisoner and roughed up by the aforementioned Private Maloney. Doubleday greeted his old comrade saying: “Archer! I’m glad to see you,” and reached out his hand to greet his friend, to which Archer replied “Well, I’m not glad to see you by a damn sight” and refused to shake Doubleday’s hand. [85]

With the Archer’s brigade whipped and Davis’s in flight Solomon Meredith pulled back the brigade and “was reforming his lines when a shell exploded near him.” [86] Meredith’s horse was killed and fell on him and the tall general was struck in the head by a shell fragment which fractured his skull and rendered him hors d ’combat for the rest of the battle.

Contrary to the reports of many of the Confederates involved, stating that they were outnumbered, some of which have achieved nearly mythic status in some accounts of the battle, the forces engaged were relatively evenly matched. [87] Clifford Dowdey says that the Iron Brigade “heavily outnumbered the one brigade they met. Archer’s….” [88] Such accounts are usually based on the reports of Heth and other confederate commanders. Heth in his after action report wrote that “Archer, encountered heavy masses in his front, and his gallant little brigade, after being almost surrounded by overwhelming forces in front and on both flanks, was forced back….” [89]

However, such was not the case. The reason for this repulse was not that the Union forces had “overwhelming forces” or “greatly superior numbers.” Instead the Archer’s brigade and the Iron Brigade were fairly evenly matched with Archer having about 1,130 men and the Iron Brigade 1,400 while Davis outnumbered Cutler nearly two to one having between 2,400 and 2,600 men in the battle to Cutler’s 1,300. [90]

Following the repulse of Archer and Davis’s brigades by Reynolds’s First Corps, Heth withdrew his badly mauled brigades back to Herr’s Ridge in order to reform them and bring up the brigades of Brockenbrough and Pettigrew before he could resume his attack. In his next assault he would also be supported by Pender’s fresh division which was now coming up.

Coddington notes that the outcome of the opening engagement came down to leadership and “the superior tactical skills of the Northern generals,” who “created a reserve force” with one regiment of the Iron Brigade which “permitted them to take full advantage of their interior lines, shift their strength about, and apply it where most needed.” [91] It was a “calculated risk,” for it assumed that the depleted Iron Brigade could handle Archer’s brigade effectively with only four of their five assigned regiments. [92] Again, even with the loss of Reynolds it was a case of Harry Heth being out-generaled, this time by Abner Doubleday. Heth “had not exercised the close field command by means of which Doubleday had won the brief, furious action.” [93]

The Death of Reynolds

Reynolds was dead, but the series of command decisions reached by Reynolds under the pressure of a meeting engagement “where neither side held an immediate advantage” [94] were critical to the army. Likewise, because he had effectively communicated his intent to his subordinate commanders they were able to continue the fight despite his death, and his superiors and successors were able to effectively continue the battle that he had initiated. When he went into action he had “barely a third of his corps available, and confronting a force of unknown size, he had put himself at the head of his troops to lead them in a vigorous attack.” [95]

Though shaken by Reynolds’ loss, the Union troops fought on at McPherson and Seminary Ridge under the command of Doubleday until the assault of Ewell on their left and the arrival of Pender’s fresh division forced them from their positions. However Reynolds’s death was a major blow for the Federal forces for it “removed from the equation the one person with enough vision and sense of purpose to manage this battle.” [96] Despite this Reynolds, by pushing forward with his troops on McPherson’s Ridge ensured that Howard was able to secure Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge, without which Gettysburg would have been lost.

The contrast between Reynolds and his opponents was marked. Hill was ten miles away from the action. Heth was too far to the rear of his troops to direct their advance when they ran into trouble and did not begin to take control until after the brigades of Davis and Archer had staggered “back up the ravine, with Davis’s temporarily wrecked.” [97] In contrast to Heth, Reynolds “hurried to the front, where he was able to inspirit the defense and throw troops into the decisive zone.” [98] At every point in the brief encounter John Reynolds showed himself superior to his opponents as he directed the battle. “Dedicated to an aggressive forward defense in the vanguard of the entire Army of the Potomac, Reynolds, at the cost of his own life had blunted the Rebel thrust and bought valuable time that permitted the balance of Meade’s army to take possession of the coveted high ground….” [99]

Though he paid for his efforts with his life but his sacrifice was not in vain. Reynolds’s tactics “gave the First Corps room for maneuver in front of Gettysburg and upset General Hill’s timetable.” [100] Harry Hunt noted: “…by his promptitude and gallantry he had determined the decisive field of the war, and he opened brilliantly a battle which required three days of hard fighting to close with a victory.” [101]

Notes

[1] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[2] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command p.261

[3] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[4] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.261

[5] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 158

[6] Nolan, Alan T. The Iron Brigade: A Military History Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN, 1961 and 1994 pp.233-234

[7] Napoleon Bonaparte, Military Maxims of Napoleon in Roots of Strategy: The Five Greatest Military Classics of All Time edited by Phillips, Thomas R Stackpole Books Mechanicsburg PA 1985 p.410

[8] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 165

[9] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.49

[10] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p.233

[11] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.159

[12] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.156

[13] Doubleday, Abner Chancellorsville and Gettysburg: Campaigns of the Civil War VI Charles Scribner’s Sons, Bew York 1882 pp.70-71

[14] Ibid. Doubleday Chancellorsville and Gettysburg p.71

[15] Carpenter, John A. Sword and Olive Branch: Oliver Otis Howard Fordham University Press, New York 1999 p.51

[16] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.76

[17] Green, A. Wilson. From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p. 70

[18] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 158

[19] Keneally, Thomas American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil war General Dan Sickles Anchor Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2003 p.275

[20] Swanberg, W.A. Sickles the Incredible Copyright by the author 1958 and 1984 Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA 1991 p.202

[21] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.156

[22] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 165

[23] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.142

[24] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.200

[25] Ibid. Doubleday Chancellorsville and Gettysburg p.68

[26] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p.235

[27] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.142

[28] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 172

[29] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.143

[30] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.172-173

[31] Schultz, Duane The Most Glorious Fourth: Vicksburg and Gettysburg July 4th 1863. W.W. Norton and Company New York and London, 2002 p.202

[32] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.173

[33] Huntington, Tom Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg PA 2013 p.154

[34] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 166

[35] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.277

[36] Doubleday, Abner. Chancellorsville and Gettysburg: Campaigns of the Civil War – VI Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1882 p.68

[37] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.75

[38] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.145

[39] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.275

[40] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.469

[41] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 pp.28-29

[42] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 34 Sears notes that in between Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, First Division of I Corps had lost a full brigade due to the expiration of enlistments.

[43] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.270

[44] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 34

[45] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.271

[46] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.275

[47] Ibid. Howard Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard 5995 of 9221

[48] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.271

[49] Girardi, Robert I. The Civil War Generals: Comrades, Peers, Rivals in Their Own Words Zenith Press, MBI Publishing, Minneapolis MN 2013 p.184

[50] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 34

[51] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p.16

[52] Tagg, Larry The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle Da Capo Press Cambridge MA 1998 Amazon Kindle Edition p.19

[53] Hebert, Walter H. Fighting Joe Hooker University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 1999. Originally published by Bobbs-Merrill, New York 1944 p.137

[54] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p.130

[55] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p. 54

[56] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p. 234

[57] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.271

[58] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day pp.75-76

[59] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.275

[60] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.271

[61] Longacre, Edward G. John Buford: A Military Biography Da Capo Press, Perseus Book Group, Cambridge MA p.194

[62] Ibid. Hunt, The First Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts p.277

[63] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.272

[64] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.96

[65] Ibid. Hunt, The First Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts p.277

[66] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.86

[67] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.96

[68] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.104

[69] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.96

[70] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.97

[71] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.112

[72] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.153

[73] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 178

[74] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.153

[75] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.109

[76] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p.20

[77] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p.173

[78] Ibid. Doubleday Chancellorsville and Gettysburg p.73

[79] Hunt, Henry. The First Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts. Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ p.277

[80] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.273

[81] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 pp.470-471

[82] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.99

[83] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.274

[84] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.271

[85] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.470

[86] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.17

[87] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.469 Even Foote in his account of Archer’s brigade makes the comment “Staggered by the ambush and outnumbered as they were….”

[88] Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.95

[89] Luvaas, Jay and Nelson Harold W editors. The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg South Mountain Press, Carlisle PA 1986 p.9

[90] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.274

[91] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.274

[92] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.274

[93] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.97

[94] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 168

[95] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.277

[96] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.171

[97] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.97

[98] Krick, Robert K. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day of Gettysburg in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.113

[99] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.12

[100] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.277

[101] Ibid. Hunt, The First Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts p.277