Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

I am pre-posting a number of articles to run this Independence Day weekend so I can work on the article that I place on posting July 4th. These are articles from my Gettysburg text that deal with events of July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd 1863 during the Battle of Gettysburg. They have all appeared on this site before in different forms, but the Battle of Gettysburg still matters, what was done there on the behalf of freedom cannot be allowed to be forgotten. .

Have a great weekend.

Peace

Padre Steve+

July 2nd 1863 was to be a pivotal day in the history of the United States, a day of valor, courage and carnage; a day where nearly 20,000 Americans were killed, wounded or missing fighting fellow Americans. It was a day where the fate of the Union and the Confederacy were in the balance. On the afternoon of that day, three volunteers rose to the challenge.

However, when we tell the story of Gettysburg or for that matter any other battle we often neglect the human costs endured by the soldiers as well as their families off the battlefield. In fact, what we know of the heroes of these battles is of their battlefield heroism as well other military or governmental service. The pictures we have of them are often the polished versions of their heroics, sometimes bordering on hagiography, criticism, if any is leveled at all, is confined to battlefield decisions or campaign plans. We mythologize them, we turn them into idols, icons and somehow, even as important and inspiring as the myths may be, we ignore their basic humanity. When we do this we often miss the more important things about their lives; those things that make them much more real, much more human, much more like us.

Sadly, the unvarnished accounts of then lives of heroes often only show up in biographies, and are seldom mentioned in the more popular accounts of battles. But the pain and suffering that these men and their families endured during and after war is sadly neglected, much to the detriment of those who idolize them.

Yes, there were many more heroes on Little Round Top that day; far too many to be covered in depth in any one work. However, these three Colonels, Strong Vincent, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Patrick “Paddy” O’Rorke along with Brigadier General Gouverneur Warren were instrumental in securing the Union victory. They were all unlikely heroes. Of these men only O’Rorke was a professional soldier, albeit a very young one, but all took to soldiering and leading soldiers as if it were second nature. They were men who along with others “who stepped out of themselves for a moment and turned a corner at some inexpressibly right instant.” [1]

Colonel Strong Vincent

I Enlisted to Fight: Strong Vincent

Colonel Strong Vincent was a 26 year old Harvard graduate and lawyer from Erie Pennsylvania. He was born in Waterford and attended school in Erie. Growing up, he worked in his father’s iron foundry, where the work helped make him a man of great physical strength. He studied at Trinity College in Hartford Connecticut and transferred to Harvard. There are various explanations for why he left Trinity, but the most interesting and probably the most credible is that during his sophomore year which was recorded by Trinity alumnus Charles F. Johnson who wrote that:

“He went calling on Miss Elizabeth Carter, a teacher at Miss Porter’s school in Farmington, ten miles west of Hartford. At some point a guard or watchman voiced a comment that impinged the lady’s virtue, and, as Johnson so aptly phrases it, Vincent “responded to the affront with the same gallantry and vigor that he was to display in the Civil War.” McCook’s account indicated that the man was repeatedly pummeled, which effectively rendered him unconscious.” [2]

Long after the war Dr. Edward Gallaudet, the president of Trinity responded to an enquiry of the circumstances leading to Vincent’s early departure from Trinity. Gallaudet responded to the request in a terse manner:

“Replying to yours of yesterday, I must say that I do not think it would be wise to make public the story I told of Strong Vincent’s escapade at Farmington & its consequences. Certainly not in the lifetime of Mrs. Vincent.” [3]

Evidently the incident resulted in Vincent leaving Trinity and the next year he entered Harvard. Vincent graduated from Harvard in 1859, ranking 51st in a class of 92. However, he was not an outstanding student and “earned admonishments on his record for missing chapel and smoking in Harvard Yard.” [4]

Returning home he studied law with a prominent lawyer and within two years had passed the bar, and he was well respected in the community. When war came and the call went out for volunteers, Vincent enlisted in a 30 Day regiment, the Wayne Guards as a private and then was appointed as a 1st Lieutenant and Adjutant of the regiment because of his academic and administrative acumen.

He married Elizabeth, the same woman whose virtue he had defended at Trinity that day. Vincent like many young northerners believed in the cause of the Union undivided, and he wrote his wife shortly after the regiment went to war on the Peninsula:

“Surely the right will prevail. If I live we will rejoice in our country’s success. If I fall, remember you have given your husband to the most righteous cause that ever widowed a woman.” [5]

When the Wayne Guards were disbanded at the end of their enlistment, Vincent helped to raise the 83rd Pennsylvania and was commissioned as a Lieutenant Colonel in it on September 14th 1861. The young officer learned his trade well and was considered a “strict disciplinarian and master of drill.” [6] That being said one enlisted man remarked that “no officer in the army was more thoughtful and considerate of the health and comfort of his men.” [7] Vincent assumed command of the regiment when the commander was killed during the Seven Days in June of 1862 where he learned lessons that he would help impart to his fellow officers as well as subordinates, including Chamberlain. At Fredericksburg any doubters about the young officer’s courage and leadership ability were converted where they observed his poise “with sword in hand” he “stood erect in full view of the enemy’s artillery, and though the shot fell fast on all sides, he never wavered or once changed his position.” [8]

By the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, the 26 year old Vincent was the youngest brigade commander in the army. He was noted for his intelligence, leadership, military acumen and maturity. One friend wrote “As a general thing his companions were older than himself….Among his associates were men of the highest rank. He could adapt himself to all, could talk with the politician on questions of history, with a general officer on military evolutions, or with a sporting man on the relative merits of horses,-and all respected his opinion.” [9]

His promotion was well earned, following a bout with a combination of Malaria and Typhoid, the “Chickahominy Fever” which almost killed him; Vincent took command of the regiment after its commander was killed at Gaines Mill. He commanded the regiment at Fredericksburg and was promoted to command the 3rd Brigade after the Battle of Chancellorsville following the resignation of its commander, Colonel T.W.B. Stockton on May 18th 1863.

Vincent was offered the chance to serve as the Judge Advocate General of the Army of the Potomac by Joseph Hooker in the spring of 1863 after spending three months on court-martial duty. But the feisty Vincent refused the offer in so that he might remain in the fight commanding troops. [10] He told his friends “I enlisted to fight.” [11]

Vincent, like Chamberlain, who admired him greatly had “become a kind of model of the citizen soldier.” [12] As a result of his experience in battle and the tenacity of the Confederate army he became an advocate of the tactics that William Tecumseh Sherman would later employ during his march to the sea in 1864. He wrote his wife before Chancellorsville:

“We must fight them more vindictively, or we shall be foiled at every step. We must desolate the country as we pass through it, and not leave a trace of a doubtful friend or foe behind us; make them believe that we are in earnest, terribly in earnest; that to break this band in twain is monstrous and impossible; that the life of every man, yea, of every weak woman or child in the entire South, is of no value whatever compared with the integrity of the Union.” [13]

Unlike most other brigade commanders, Vincent was still a Colonel, and he, like many others would in his place hoping for a General’s star. He remarked that his move to save Sickles’ command “will either bring me my stars, or finish my career as a soldier.” [14] On July first, Vincent, a native Pennsylvanian came to Hanover and learning that battle had been joined, ordered “the pipes and drums of the 83rd Pennsylvania to play his brigade through the town and ordered the regiments to uncover their flags again….” [15] As the brigade marched through the town, Vincent “reverently bared his head” and announced to his adjutant, “What death more glorious can any man desire than to die on the soil of old Pennsylvania fighting for that flag?” [16]

Vincent was known for his personal courage and a soldier of the 83rd Pennsylvania observed: “Vincent had a particular penchant for being in the lead….Whenever or wherever his brigade might be in a position to get ahead…, he was sure to be ahead.” [17] That courage and acumen to be in the right place at the right time was in evidence when he led his brigade into battle on that fateful July second.

On July 2nd Barnes’ division of V Corps, which Vincent’s brigade was a part was being deployed to the threat posed by the Confederate attack of McLaws’ division on the Peach Orchard and the Wheat Field to reinforce Sickles’ III Corps. While that division marched toward the Peach Orchard, Vincent’s 3rd Brigade was the trail unit. When Gouverneur Warren’s aide, Lieutenant Randall Mackenzie [18] came toward the unit in search of Barnes, he came across Vincent and his brigade near the George Weikert house on Cemetery Ridge awaiting further orders. [19]

Vincent intercepted him and demanded what his orders were. Upon being told that Sykes’ orders to Barnes were to “send one of his brigades to occupy that hill yonder,” [20] Vincent defied normal protocol assuming that Barnes had hit the bottle and was drunk [21] and told Mackenzie “I will take responsibility of taking my brigade there.” [22] Vincent immediately went into action and ordered Colonel James Rice, his friend and the commander of the 44th New York “to bring the brigade to the hill as quickly as possible,” and then turned on his horse and galloped off toward Little Round Top.” [23]

It was a fortunate thing for the Union that he did. His quick action to get his brigade, clear orders to his subordinate commanders and skilled analysis of the ground were a decisive factor in the Union forces holding Little Round Top. After ordering Colonel Rice to lead the brigade up to the hill, he and his aide went forward to scout positions accompanied by the brigade standards. Rice brought the brigade forward at the double quick “across the field to the road leading up the north shoulder of the hill” with Chamberlain’s 20th Maine in the lead. [24]

Vincent and his orderly made a reconnaissance of the south and east slope of the hill which adjoined a small valley and a rocky outcrop called Devil’s Den, which was occupied by the 124th New York and which was the end of Sickles’ line. Near the summit of the southern aspect of the hill, they came under Confederate artillery fire and told his orderly “They are firing at the flag, go behind the rocks with it.” [25]

Vincent dismounted, leaving his sword secured on his horse, carrying only his riding crop. He continued and “with the skill and precision of a professional had reconnoitered and decided how to best place his slim brigade of 1350 muskets.” [26] He chose a position along a spur of the hill, which now bears his name, running from the northwest to the southeast to place his regiments where they could intercept the Confederate troops of Hood’s division which he could see advancing toward the hill.

What Vincent saw when he arrived was a scene of disaster. Confederate troops had overwhelmed the 124th New York and were moving on Little Round Top, “Devil’s Den was a smoking crater,” and the ravine which separated Devil’s Den from Little Round Top “was a whirling maelstrom.” [27] Seeing the threat Vincent began to deploy his brigade but also sent at messenger back to Barnes telling him “Go tell General Barnes to send reinforcements at once, the enemy are coming against us with an overwhelming force” [28]

The 16th Michigan, the smallest regiment in his brigade with barely 150 soldiers in line [29] was placed on the right flank of the brigade. As it moved forward, its adjutant, Rufus W. Jacklin’s horse was hit by a cannon ball which decapitated that unfortunate animal and left it “a mass of quivering flesh.” [30] A fierce Confederate artillery barrage fell among the advancing Union troops and splintered trees, causing some concern among the soldiers. The 20th Maine’s Chaplain, Luther French, saw the “beheading of Jacklin’s horse and ran to Captain Atherton W. Clark, commanding the 20th’s Company E, babbling about what he had seen. Clark interrupted French abruptly and shouted: “For Christ sake Chaplain, if you have any business attend to it.” [31]

That section of the line was located on massive boulders that placed it high above the valley below, making it nearly impregnable to frontal attack. On the summit Vincent deployed the 83rd Pennsylvania and 44th New York to their left at the request of Rice who told him “In every battle that we have engaged the Eighty-third and Forty-fourth have fought side by side. I wish that it might be so today.” [32] The story is probably apocryphal but the regiments remained side by side with the 16th Michigan on the right and the 20th Maine on the left. The two regiments were deployed below the crest among the large number of boulders; the 83rd was about two-thirds of the way down the way down the slope where it joined the right of the 44th, whose line angled back up the slope to the southeast. A historian of the 83rd Pennsylvania noted that “Each rock”… “was a fortress behind which the soldier[s] instantly took shelter.” [33] The soldiers were determined to do their duty as they now were fighting on home ground.

Vincent deployed the 20th Maine on his extreme left of his line, and in fact the extreme end of the Union line. Vincent knew that if this flank was turned and Chamberlain overrun that it would imperil the entire Union position. Vincent came up to Chamberlain who remembered that Vincent said “in an awed, faraway voice: “I place you here….This is the left of the Union line. You understand. You are to hold this ground at all costs.” [34] Chamberlain acknowledged his understanding of the order and since the regiment lacked field grade officers, Chamberlain “assigned Captain Atherton Clark of company E to command the right wing, and acting Major Ellis Spear the left.” [35]

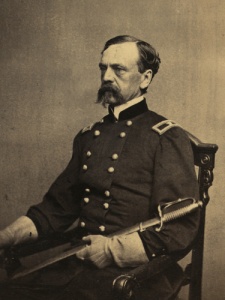

Colonel Joshua Chamberlain following his Promotion to Brigadier General

The Professor: Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

While Colonel Joshua Chamberlain’s story is much better known than his brigade commander, Strong Vincent, he was another of the citizen soldiers whose performance and leadership on Little Round Top saved the Union line that hot July evening. Chamberlain was a graduate of Bowdoin College and Bangor Theological Seminary. Fluent in nine languages other than English, he remained at Bowdoin as Professor of Rhetoric and was deeply unhappy at missing the war even as his students left and were commissioned as officers in newly raised regiments.

In June of 1862 Chamberlain wrote to Governor Israel Washburn requesting an appointment in a newly raised Maine Regiment without consulting either the college or his wife Fannie, who was “shocked, hurt, and alarmed by the decision he had made without consulting her…She remonstrated, she raised her voice, and quite possibly wept over the injustice he had done to both by this unilateral act that threatened to send their world careening in all directions.” [36]

As far as Bowdoin went, Chamberlain actually deceived the college by requesting a “scholarly sabbatical when in fact he had applied to the governor of Maine in the new 20th Maine Infantry in the late summer of 1862.” [37] When the faculty of Bowdoin found out of Chamberlain’s action many of them “were livid over what they considered his duplicity, and some shunned him during the brief period that he remained in Brunswick before reporting to training camp. [38]

The letter that Chamberlain wrote to Governor Israel Washburn details Chamberlain’s desire to serve and in some ways shows his considerable political skill in presenting his case to join the army:

“For seven years past I have been Professor in Bowdoin College. I have always been interested in military matters, and what I do not know in that line I know how to learn.

Having been lately elected to a new department here, I am expecting to have leave, at the approaching Commencement, to spend a year or more in Europe, in the service of the College. I am entirely unwilling, however, to accept this offer, if my Country needs my service or example here.

Your Excellency presides over the Educational as well as the military affairs of our State, and, I am well aware, appreciates the importance of sustaining our Institutions of Learning. You will therefore be able to decide where my influence is most needed.

But, I fear, this war, so costly of blood and treasure, will not cease until the men of the North are willing to leave good positions, and sacrifice the dearest personal interests, to rescue our Country from Desolation, and defend the National Existence against treachery at home and jeopardy abroad. This war must be ended, with a swift and strong hand; and every man ought to come forward and ask to be placed at his proper post.

Nearly a hundred of those who have been my pupils, are now officers in our army; but there are many more all over our State, who, I believe, would respond with enthusiasm, if summoned by me, and who would bring forward men enough to fill up a Regiment at once. I can not free myself from my obligations here until the first week in August, but I do not want to be the last in the field, if it can possibly be helped.” [39]

Chamberlain’s pre-war experiences gave no indication that he would emerge as a military hero. His father, a veteran of the War of 1812 had named him after Captain James Lawrence, the commanding officer of the frigate USS Chesapeake in the War of 1812 who uttered the famous words “Don’t give up the ship” as he lay mortally wounded when that ship was defeated by the HMS Shannon off Boston Harbor in 1813. However, Chamberlain’s mother added the name Joshua as his first name in the town’s books. While his father hoped that the young Chamberlain would pursue a military career, his mother earnestly desired that he would pursue a ministerial career. Chamberlain did become a licensed minister but had no desire to become a pastor, and was never ordained. This was reinforced by Fannie, who though the daughter of a minister was “too much a free thinker” and “did not share the devotion her father and Chamberlain held for organized religion.” [40]

Chamberlain debated attending West Point after graduation, a path that his classmate Oliver O. Howard took. Instead he attended Bangor Theological Seminary and following graduation took up his academic career at Bowdoin. It was during this time that he met, fell in love with, pursued, courted and finally married Frances Caroline Adams, who played the organ at the local Congregational Church that he attended. Known by most as “Fannie,” she was the adopted daughter of the eminent Congregationalist minister, Dr. George Adams who served as pastor. Fannie had a strong independent streak and was as an accomplished musician and artist.

The couple was an interesting match. Chamberlain was impressed by Fannie’s “artistic gifts. Fannie had talent not only in music but in poetry and, especially; art…” [41] but he ignored potential areas of conflict that would create difficulties throughout their marriage. However, Fannie was beset by numerous fears, as well as a desire not to be dominated by any man. Chamberlain pursued her with abandon but for a time she resisted, until her widowed father married a woman not much older than herself. She desired to pursue the study of music and went away to New York to do so, but in 1852 she decided that she was in love with him. “Yet she harbored doubts about her ability to return his feelings for her measure for measure.” [42]

Fannie suffered from depression and a constant worry about her eyesight which began failing her and an early age. It was a malady that eventually left her completely blind by then turn of the century. Compounding her struggles was that fact that her new husband struggled with his own doubts and depression, a depression that only seamed to lift during the war years.

“During most of his life, Chamberlain struggled with bouts of deep depression and melancholy. But not during the war years. It was as if the war and soldiering had made a new man out of him.” [43]

Chamberlain was offered command of the 20th Maine but asked Governor Washburn that he was appointed as a Lieutenant Colonel, which he was in August 1862. He fought with the regiment at Fredericksburg and was named commander of it when Colonel Adelbert Ames, his commander was transferred to preform staff duties prior to obtaining a brigade command in Oliver Howard’s XI Corps following the debacle at Chancellorsville.

Chamberlain at his heart, through his association with abolitionists and other prior to the war was a staunch Unionist. Before going into the army he wrote:

“We have this war upon is & we want to stop it. It has cost us already too much precious blood. It has carried stagnation, starvation & grief in to too many villages of our fair land – brought death to too many noble hearts that we could ill afford to lose. But the only way to stop this war, is first to show that we are strongest…I feel that we are fighting for our country – for our flag- not as so many Stars and Stripes, but as the emblem of a good & powerful nation – fighting to settle the question whether we are a nation or a basket of chips. Whether we shall leave our children the country we have inherited – or leave them without a country – without a name – without a citizenship among the great nations of the earth – take the chief city of the rebels. They will have no respect for us unless we whip them & and I say it in all earnestness….” [44]

Like Vincent, Chamberlain was also a quick student or military science and rapidly adapted to being a soldier, officer and commander of troops in combat. He spent as much time studying the art of war under the supervision of Colonel Ames including Henri Jomini’s Art of War which he wrote to Fannie “The Col. & I are going to read it. He to instruct me, as he is kindly doing everything now.” [45] He excelled at his studies under Ames, but since most of the manuals that he studied were based on Napoleonic tactics and had not incorporated the changes brought about by the rifled musket, Chamberlain like so many others would have to learn the lesson of war the hard way.

Chamberlain was with the regiment at Antietam, but it saw no action. He was in the thick of the fighting at Fredericksburg and Burnside’s subsequent “Mud March” which were both disastrous for the army.

He took command of the regiment in late April after Ames left on detached duty before assuming a brigade command. As the new commander of the regiment, Chamberlain and the 20th Maine missed the Battle of Chancellorsville as the regiment had been quarantined due to an epidemic of smallpox, which they had probably received from “poorly prepared serum with which the regiment was vaccinated” [46] in April.

From the regiment’s quarantined location Chamberlain and his men could hear the sound of battle. One of his soldiers wrote “We could hear the firing plain but there we lay in glorious idleness without being able to lift a finger or fire a gun.” [47] In frustration Chamberlain rode to Major General Joseph Hooker’s headquarters and asked Hooker’s Chief of Staff Dan Butterfield for the chance to enter the fight. Refused the chance Chamberlain told Butterfield “If we couldn’t do anything else we would give the rebels the smallpox!” [48] The regiment spent the battle guarding a telegraph line must to Chamberlain and his soldier’s disgust.

On the march up to Gettysburg, Chamberlain was ordered to take a number of veterans of the 2nd Maine who had signed three year, rather than two year enlistment contracts and were angry at remaining in the army when the regiment was mustered out. The men were angry and Chamberlain was given permission by Meade to fire on them “if they refused to do duty. The new colonel realized he had a crisis on his hands.” [49] The soldiers were bitter but Chamberlain treated them graciously and “almost all of them agreed to take up their muskets again the service of the 20th Maine.” [50] Chamberlain later remarked of how these men “we’re afterward among my best men, worthy of the proud fame of the 2nd, and the hard earned laurels of the 20th.” [51]

On receiving his orders from Vincent, Chamberlain deployed his small regiment halfway down the southern slope facing the small valley between Little Round Top and Big Round Top. By the time he arrived at Gettysburg he had become “a great infantry officer, and among his valuable qualities was [understanding] where an attack would come….” [52]

Since Chamberlain’s account is so important I will forgo a discussion of his tactics and instead quote the sections of his after action report that explains his actions. Chamberlain wrote:

“On reaching the field at about 4 p.m. July 2d, Col. Vincent commanding the Brigade, placing me on the left of the Brigade and consequently on the extreme left of our entire line of battle, instructed me that the enemy were expected shortly to make a desperate attempt to turn our left flank, and that the position assigned to me must be held at every hazard.

I established my line on the crest of a small spur of a rocky and wooded hill, and sent out at once a company of skirmishers on my left to guard against surprise on that unprotected flank.

These dispositions were scarcely made when the attack commenced, and the right of the Regt. found itself at once hotly engaged. Almost at the same moment, from a high rock which gave me a full view of the enemy, I perceived a heavy force in rear of their principal line, moving rapidly but stealthily toward our left, with the intention, as I judged, of gaining our rear unperceived. Without betraying our peril to any but one or two officers, I had the right wing move by the left flank, taking intervals of a pace or two, according to the shelter afforded by rocks or trees, extending so as to cover the whole front then engaged; and at the same time moved the left wing to the left and rear, making a large angle at the color, which was now brought to the front where our left had first rested.

This hazardous maneuvre [sic] was so admirably executed by my men that our fire was not materially slackened in front, and the enemy gained no advantage there, while the left wing in the meantime had formed a solid and steady line in a direction to meet the expected assault. We were not a moment too soon; for the enemy having gained their desired point of attack came to a front, and rushed forward with an impetuosity which showed their sanguine expectations.

Their astonishment however was evident, when emerging from their cover, they met instead of an unsuspecting flank, a firm and ready front. A strong fire opened at once from both sides, and with great effect, the enemy still advancing until they came within ten paces of our line, where our steady and telling volleys brought them to a stand. From that moment began a struggle fierce and bloody beyond any that I have witnessed, and which lasted in all its fury, a full hour. The two lines met, and broke and mingled in the shock. At times I saw around me more of the enemy than of my own men. The edge of conflict swayed to and fro -now one and now the other party holding the contested ground. Three times our line was forced back, but only to rally and repulse the enemy. As often as the enemy’s line was broken and routed, a new line was unmasked, which advanced with fresh vigor. Our “sixty rounds” were rapidly reduced; I sent several messengers to the rear for ammunition, and also for reinforcements. In the mean time we seized the opportunity of a momentary lull to gather ammunition and more serviceable arms, from the dead and dying on the field. With these we met the enemy’s last and fiercest assault. Their own rifles and their own bullets were turned against them. In the midst of this struggle, our ammunition utterly failed. The enemy were close upon us with a fresh line, pouring on us a terrible fire. Half the left wing already lay on the field. Although I had brought two companies from the right to its support, it was now scarcely more than a skirmish line. The heroic energy of my officers could avail no more. Our gallant line withered and shrunk before the fire it could not repel. It was too evident that we could maintain the defensive no longer. As a last desperate resort, I ordered a charge. The word “fix bayonets” flew from man to man. The click of the steel seemed to give new zeal to all. The men dashed forward with a shout. The two wings came into one line again, and extending to the left, and at the same time wheeling to the right, the whole Regiment described nearly a half circle, the left passing over the space of half a mile, while the right kept within the support of the 83d Penna. thus leaving no chance of escape to the enemy except to climb the steep side of the mountain or to pass by the whole front of the 83d Penna. The enemy’s first line scarcely tried to run-they stood amazed, threw down their loaded arms and surrendered in whole companies. Those in their rear had more time and gave us more trouble. My skirmishing company threw itself upon the enemy’s flank behind a stone wall, and their effective fire added to the enemy’s confusion. In this charge we captured three hundred and sixty eight prisoners, many of them officers, and took three hundred stand of arms. The prisoners were from four different regiments, and admitted that they had attacked with a Brigade.” [53]

Colonel William Oates of the 15th Alabama gave Chamberlain and his regiment the credit for stopping his attack. Oates wrote: “There have never been harder fighters than the Twentieth Maine and their gallant Colonel. His skill and persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat.” [54]

As with any firsthand account, aspects of Chamberlain’s accounts are contested by others at the scene. But in another way Chamberlain’s accounts of battle have to be carefully examined, because they often reflect his romanticism, and because he was not always a realist. Unlike others in his command like Major Ellis Spear, who played such an important role on Little Round Top that day, a realist who “saw things plainly and remembered them clearly, in stark, unadorned hues. Joshua Chamberlain was a romanticist; even when describing the horrors of bloodbath his prose could be colorful, lyrical, even poetic.” [55]

There are accounts that differ from Chamberlain’s; Oates wrote that he ordered the retreat and that there were not as many prisoners taken as Chamberlain states. Likewise, one of Chamberlain’s company commanders disputed the account of the Chamberlain’s order of the bayonet charge. But even these accounts take nothing away from what Chamberlain accomplished that day. The fact is that Chamberlain’s regiment was outnumbered nearly two to one by the 4th 15th and 47th Alabama regiments. Chamberlain “offset this superiority with strength of position, iron determination and better tactics.” [56]

While the actions of Chamberlain, Vincent, Warren and others on the Union side, another factor was at play. This was the fatigue of the Confederate soldiers. The regiments attacking Little Round Top and their parent unit, Law’s brigade of Hood’s division, had conducted a grueling 28 mile march to get to the battlefield. By the time that they arrived and made their assault, most soldiers were exhausted and dehydrated. This was something that their commander, Colonel Oates believed was an important factor in what happened. While Oates gives tremendous credit to Chamberlain and the 20th Maine he wrote that the fatigue and dehydration of his soldiers “contributed largely to our failure at Little Round Top.” [57]

Vincent was mortally wounded while leading the defense of the hill. As the men of Robertson’s Texas brigade rushed the hill and threatened to crack “the stout 16th Michigan defense…” [58] Vincent rushed to bolster the defenders. He was standing on a large boulder with a riding crop as the men of the 16th Michigan were beginning to waiver. Fully exposed to enemy fire he attempted to drive the retreating men back into the fight. Brandishing the riding which he cried out: “Don’t yield an inch now men or all is lost,” [59] and moments later was struck by a “minié ball which passed through his left groin and lodged in his left thigh. He fell to the ground and as he was being carried from the field, “This is the fourth or fifth time they have shot at me…and they have hit me at last.” [60]

Colonel Patrick “Paddy” O’Rorke

The Irish Regular: Paddy O’Rorke

To Vincent’s right another hero emerged, Colonel Patrick “Paddy” O’Rorke; the young 27 year old Colonel of the 140th New York. O’Rorke was born in County Cavan, Ireland in 1836. His family immigrated to the United States, settling in Rochester, New York during the great wave of Irish immigration between 1838 and 1844. There the young O’Rorke worked hard to overcome the societal prejudices against Irish Catholics. After he completed his secondary education, he worked as a marble cutter before obtaining an appointment to West Point in 1857. He was the only foreign born member of his class at the academy from which he graduated first in his class in 1861. “Aggressive and bold, there was also something that implied gentility and tenderness…Beneath the mettle of a young professional soldier was a romantic heart that could croon a ballad before wielding the sword.” [61] O’Rorke married his childhood, schoolmate, fellow parishioner and childhood sweetheart, Clarissa Wadsworth Bishop, in the summer of 1862 and shortly thereafter accepted a commission as colonel of the 140th New York Infantry.

At Gettysburg, O’Rorke was with Weed’s brigade when Gouverneur Warren found him as he attempted to get any available troops to the summit of Little Round Top. When Warren found O’Rorke, who had been one of his students at West Point, he ordered him to follow him up the hill, saying “Paddy…give me a regiment.” [62] When O’Rorke said that Weed expected him to be following him, Warren took the responsibility telling O’Rorke “Bring them up on the double quick, and don’t stop for aligning. I’ll take responsibility.” [63] O’Rorke followed with his gallant regiment with the rest of the brigade under Weed following behind them.

The 140th New York’s entrance onto the summit of Little Round Top must have been dramatic. Dressed in new Zouave uniforms that they had been issued in early June “the men were “jaunty but tattered” in baggy blue trousers, red jackets, and fezzes.” [64] O’Rorke’s New Yorkers entered the battle to the right of the Vincent’s 16th Michigan, which was being swarmed by the 4th and 5th Texas and 4th Alabama, who thought that victory was at hand. O’Rorke did not even take time to form his men for battle but drew his sword and yelled, “Down this way boys!” [65] His troops responded magnificently slamming into the surprised Texans and Alabamians and “at once the Confederate assault began to dissolve” [66]

O’Rorke’s troops smashed into the surging Rebel ranks, stopping the Confederate assault in its tracks and taking over two-hundred prisoners. As O’Rorke “valiantly led his men into battle, surging down the hill toward the shelf of rock so recently vacated by the right wing of the 16th Michigan, he paused for a moment to cheer his men on and wave them forward. When he did, he was struck in the neck by an enemy bullet….O’Rorke, killed instantly slumped to the ground.” [67] But his regiment “had the initiative now. More and more men piled into a sloppy line, firing as fast as they could reload. Their dramatic appearance breathed renewed life into the other Union regiments on the hill, which now picked up their firing rates.” [68] The gallant young Irish colonel was dead, but he and his regiment had saved Vincent’s right flank. The regiment had suffered fearfully, “with 183 men killed or wounded, but they had managed to throw back the Texans. The adjutant of the 140th estimated that they came within sixty seconds of losing the top of the hill.” [69] O’Rorke’s soldiers were enraged by the death of their beloved colonel and picked out the Confederate who had killed him. One of the soldiers wrote “that was Johnny’s last shot, for a number of Companies A and G fired instantly.” It was said that this particular Johnny was hit, by actual count, seventeen times.” [70] Now led by company commanders the 140th stayed in the fight and solidified and extended the Federal line in conjunction with the rest of Weed’s brigade to their right.

The actions of Chamberlain’s, Vincent’s, and O’Rorke’s soldiers shattered Hood’s division. “Casualties among the Alabamians, Texans, and Georgians approached or exceeded 2,000. In the Texas Brigade commander Robertson had been wounded, three regimental commanders had fallen killed or wounded, and nearly all of the field officers lay on the ground.” [71]

The badly wounded Strong Vincent was taken to a field hospital at the Weikert farm where he lingered for five days before succumbing to his wounds. In the yard lay the body of Paddy O’Rorke whose regiment had saved his brigade’s right flank. Vincent knew that he was dying and he requested that a message be sent to Elizabeth for her to come to Gettysburg. It did not reach her in time. Though he suffered severe pain he bravely tried not to show it. Eventually he became so weak that he could no longer speak. “On July 7, a telegram from President Lincoln, commissioning Vincent a brigadier general, was read to him, but he could not acknowledge whether he understood that the president had promoted him for bravery in the line of duty.” [72] He died later that day and his body was transported home to Erie for burial. Ten weeks after his death his wife gave birth to a baby girl. The baby would not live a year and was buried next to him.

Colonel Rice, who led the 44th New York up the hill and took command of the brigade on Vincent’s death, memorialized his fallen commander in his general order to the brigade on July 12th:

“The colonel commanding hereby announces to the brigade the death of Brig. Gen. Strong Vincent. He died near Gettysburg, Pa., July 7, 1863, from the effects of a wound received on the 2d instant, and within sight of that field which his bravery had so greatly assisted to win. A day hallowed with all the glory of success is thus sombered by the sorrow of our loss. Wreaths of victory give way to chaplets of mourning, hearts exultant to feelings of grief. A soldier, a scholar, a friend, has fallen. For his country, struggling for its life, he willingly gave his own. Grateful for his services, the State which proudly claims him as her own will give him an honored grave and a costly monument, but he ever will remain buried in our hearts, and our love for his memory will outlast the stone which shall bear the inscription of his bravery, his virtues, and his patriotism.

While we deplore his death, and remember with sorrow our loss, let us emulate the example of his fidelity and patriotism, feeling that he lives but in vain who lives not for his God and his country. “[73]

Vincent’s wife Elizabeth never married again and was taken in by the Vincent family. Vincent’s younger brother became an Episcopal Priest and Bishop and later provided a home for her. She became a tireless worker in the church working with charitable work for young women and children. This led to an interest in sacred art and she wrote two books: Mary, the Mother of Jesus and The Madonna in Legend and in Art. She also translated Delitzch’s Behold the Man and A Day in Capernaum from the German. [74] Elizabeth Vincent passed away in April 1914 and was buried beside her husband and daughter.

After the battle, as the army looked to replace the casualties in the ranks of senior leadership and “when Colonel Rice, in charge of 3rd Brigade after Vincent fell, was promoted to brigadier general and given another command” the new division commander Major General Charles Griffin, “insisted on having Chamberlain, for the 3rd Brigade.” [75]

Chamberlain survived the war to great acclaim being wounded three times, once during the siege of Petersburg the wound was so severe that his survival was in doubt and General Ulysses S. Grant promoted him on the spot. It was the only promotion that Grant gave on the field of battle. Grant wrote:

“He had been several times recommended for a brigadier-generalcy for gallant and meritorious conduct. On this occasion, however, I promoted him on the spot, and forwarded a copy of my order to the War Department, asking that my act might be confirmed without any delay. This was done, and at last a gallant and meritorious officer received partial justice at the hands of his government, which he had served so faithfully and so well.” [76]

He recovered from the wound, and was promoted to Major General commanding a division and awarded the Medal of Honor. He received the surrender of John Gordon’s division of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox on April 9th 1865. When he did he ordered his men to present arms in honor of their defeated foe as those haggard soldiers passed his division. It was an act that helped spur a spirit of reconciliation in many of his former Confederate opponents.

The Hidden Side of the Hero: Post War Struggles

Chamberlain’s accolades were certainly earned but others on that hill have been all too often overlooked by most people. This list includes Gouverneur Warren who was humiliated by Phillip Sheridan at Five Forks, Strong Vincent who died on of wounds suffered on Little Round Top and Paddy O’Rorke, the commander of the 140th New York of Weed’s Brigade on Vincent’s right who was mortally wounded that day.

After the war like most citizen soldiers, Chamberlain returned to civilian life, and a marriage that was in crisis in which neither Joshua nor Fannie seemed able to communicate well enough to mend. The troubled couple “celebrated their tenth wedding anniversary on December 7, 1865. He gave her a double banded gold-and-diamond bracelet from Tiffany’s, an extravagant gift that only temporarily relieved the stresses at work just below the surface of their bland marriage. Wartime separation had perhaps damaged it more than Chamberlain knew.” [77]

When he came home Chamberlain was unsettled. Fannie quite obviously hoped that his return would reunite them and bring about “peaceful hours and the sweet communion of uninterrupted days with the husband that had miraculously survived the slaughter” [78] and who had returned home, but it was not to be. Army life had given him a sense of purpose and meaning that he struggled to find in the civilian world. He was haunted by a prediction made by one of his professors. A prediction that “he would return from war “shattered” & “good for nothing,” [79] Chamberlain began to search for something to give his life meaning. He began to write a history of V Corps and give speeches around the northeast, and “these engagements buoyed his spirit, helping him submerge his tribulations and uncertainties in a warm sea of shared experience. [80] In his travels he remained apart from Fannie, who remained with the children, seldom including her in those efforts. She expressed her heart in a letter in early 1866:

“I have no idea when you will go back to Philadelphia, why dont you let me know about things dear?….I think I will be going towards home soon, but I want to hear from you. What are you doing dear? are you writing for your book? and how was it with your lecture in Brunswick- was it the one at Gettysburg? I look at your picture when ever I am in my room, and I am lonely for you. After all, every thing that is beautiful must be enjoyed with one you love, or it is nothing to you. Dear, dear Lawrence write me one of the old letters…hoping to hear from you soon…I am as in the old times gone bye Your Fannie.” [81]

In those events he poured out his heart in ways that seemed impossible for him to do with Fannie. He accounted those wives, parents, sons and daughters at home who had lost those that they loved, not only to death:

“…the worn and wasted and wounded may recover a measure of their strength, or blessed by your cherishing care live neither useless nor unhappy….A lost limb is not like a brother, an empty sleeve is not like an empty home, a scarred breast is not like a broken heart. No, the world may smile again and repair its losses, but who shall give you back again a father? What husband can replace the chosen of your youth? Who shall restore a son? Where will you find a lover like the high hearted boy you shall see no more?” [82]

Chamberlain set his sights on politics, goal that he saw as important in championing the rights of soldiers and their well treatment by a society, but a life that again interrupted his marriage to Fannie and brought frequent separation. Instead of the one term that Fannie expected, Chamberlain ended up serving four consecutive one year terms as Governor of Maine, and was considered for other political offices. However, the marriage continued to suffer and Fannie’s “protracted absence from the capital bespoke her attitude toward his political ambitions.” [83] Eventually Chamberlain returned home and. “For twelve years following his last term as governor, he served as president of Bowdoin College, his alma mater. [84]

He became a champion of national reconciliation admired by friend and former foe alike, but he returned with bitterness towards some in the Union who he did not believe cared for his comrades or their families, especially those who had lost loved ones in the war. While saluting those who had served in the Christian and Sanitary Commissions during the war, praising veterans, soldiers and their families he noted that they were different than:

Those who can see no good in the soldier of the Union who took upon his breast the blow struck at the Nation’s and only look to our antagonists for examples of heroism- those over magnanimous Christians, who are so anxious to love their enemies that they are willing to hate their friends….I have no patience with the prejudice or the perversity that will not accord justice to the men who have fought and fallen on behalf of us all, but must go round by the way of Fort Pillow, Andersonville and Belle Isle to find a chivalry worthy of praise.” [85]

Chamberlain’s post-war life, save for the times that he was able to revisit the scenes of glory and be with his former comrades was marred by deep personal and professional struggles and much suffering. He struggled with the adjustment to civilian life, which for him was profoundly difficult. He “returned to Bowdoin and the college life which he had sworn he would not again endure. Three years of hard campaigning however, had made a career of college teaching seem less undesirable, while his physical condition made a permanent army career impossible.” [86] The adjustment was more than even he could anticipate, and the return to the sleepy college town and monotony of teaching left much to be desired.

These are not uncommon situations for combat veterans to experience, and Joshua Chamberlain, the hero of Little Round Top who was well acquainted with the carnage of war, suffered immensely. His wounds never fully healed and he was forced to wear what would be considered an early form of a catheter and bag. In 1868 he was awarded a pension of thirty dollars a month for his Petersburg wound which was described as “Bladder very painful and irritable; whole lower part of abdomen tender and sensitive; large urinal fistula at base of penis; suffers constant pain in both hips.” [87] Chamberlain struggled to climb out of “an emotional abyss” in the years after the war. Part was caused by his wounds which included wounds to his sexual organs, shattering his sexuality and caused his marriage to deteriorate.

He wrote to Fannie in 1867 about the “widening gulf between them, one created at least in part by his physical limitations: “There is not much left in me to love. I feel that all too well.” [88] Chamberlain’s inability to readjust to civilian life following the war, and Fanny’s inability to understand what he had gone through during it caused great troubles in their marriage. Chamberlain “felt like hell a lot of the time, morose in mood and racked with pain.” [89] His wounds would require more surgeries, and in “April 1883 he was forced to have extensive surgery on his war wounds, and through the rest of the decade and well into the next he was severely ill on several occasions and close to death once.” [90]

By 1868 the issues were so deep that Fannie threatened him with divorce and was accusing Joshua of domestic abuse, not in court, but among her friends and in town; a charge which he contested. It is unknown if the abuse actually occurred and given Chamberlain’s poor physical condition it is unlikely that he could have done what she claimed, it is actually much more likely, based on her correspondence as well as Fannie’s:

“chronic depression, her sense of being neglected of not abandoned, and her status as an unappreciated appendage to her husband’s celebrated public career caused her to retaliate in a manner calculated to get her husband’s attention while visiting on him some of the misery she had long endured.” [91]

The bitterness in their relationship at the time was shown in his offer to her of a divorce; a condition very similar to what many combat veterans and their families experience today. After he received news of the allegations that Fannie was spreading among their friends around town, Chamberlain wrote to her:

“If it is true (as Mr. Johnson seems to think there is a chance of its being) that you are preparing for an action against me, you need not give yourself all this trouble. I should think we had skill enough to adjust the terms of a separation without the wretchedness to all our family which these low people to whom it would seem that you confide your grievances & plans will certainly bring about.

You never take my advice, I am aware. But if you do not stop this at once it will end in hell.” [92]

His words certainly seem harsh, especially in our time where divorce, be it contested or uncontested does not have the same social stigma it did then. Willard Wallace writes that the letter “reflects bewilderment, anger, even reproof, but not recrimination; and implicit throughout is an acute concern for Fanny, who did not seem to realize the implications of legal action. The lot of a divorcee in that era in a conservative part of the country was not likely to be a happy one.” [93]This could well be the case, but we do not know for sure his intent. We can say that it speaks to the mutual distress, anger and pain that both Joshua and Fannie were suffering at the time.

The marriage endured a separation which lasted until 1871 when his final term of office expired they reconciled, and the marriage did survive, for nearly forty more years. “Whatever differences may have once occasionally existed between Chamberlain and Fanny, the two had been very close for many years.” [94] The reconciliation could have been for any number of reasons, from simple political expedience, in that he had been rejected by his party to be appointed as Senator, and the realization that “that politics, unlike war, could never stir his soul.” [95] Perhaps he finally recognized just how badly he had hurt her over all the years of his neglect of her needs. But it is just as likely that deep in his heart he really did love her despite his chronic inability for so many years to demonstrate it in a way she could feel. Fannie died in 1905 and Chamberlain, who despite all of their conflicts loved her and grieved her, a grief “tinged with remorse and perhaps also with guilt.” [96] The anguished widower wrote after her death:

“You in my soul I see, faithful watcher, by my cot-side long days and nights together, through the delirium of mortal anguish – steadfast, calm, and sweet as eternal love. We pass now quickly from each other’s sight, but I know full well that where beyond these passing scenes you shall be, there will be heaven!”

Chamberlain made a final trip to Gettysburg in May of 1913. He felt well enough to give a tour to a delegation of federal judges. “One evening, an hour or so before sunset, he trudged, alone, up the overgrown slope of Little Round Top and sat down among the crags. Now in his Gothic imagination, the ghosts of the Little Round Top dead rose up around him….he lingered up the hillside, an old man lost in the sepia world of memory.” [97] He was alone.

Chamberlain died on a bitterly cold day, February 24th 1914 of complications from complications of the ghastly wound that he received at Petersburg in 1864. The Confederate minié ball that had struck him at the Rives’ Salient finally claimed his life just four months shy of 50 years since the Confederate marksman found his target.

Sadly, the story of the marriage of Joshua and Fannie Chamberlain is all too typical of many military marriages and relationships where a spouse returns home changed by their experience of war and struggles to readjust to civilian life. This is something that we need to remember when we encounter those changed by war and the struggles of soldiers as well as their families; for if we have learned nothing from our recent wars it is that the wounds of war extend far beyond the battlefield, often scarring veterans and their families for decades after the last shot of the war has been fired.

The Battle for Little Round Top which is so legendary in our collective history and myth was in the end something more than a decisive engagement in a decisive battle. It was something greater and larger than that, it is the terribly heart wrenching story of ordinary, yet heroic men like Vincent, Chamberlain and O’Rorke and their families who on that day were changed forever. As Chamberlain, ever the romantic, spoke about that day when dedicating the Maine Monument in 1888; about the men who fought that day and what they accomplished:

“In great deeds, something abides. On great fields, something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls… generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream; and lo! the shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.” [98]

Notes

[1] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.462

[2] Nevins, James H. And Styple What Death More Glorious: A Biography of General Strong Vincent Belle Grove Publishing Co, Kearny N.J. 1997 p.16

[3] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.17

[4] Ibid. LaFantasie, Glenn W. Twilight at Little Round Top: p.105

[5] ________. Erie County Historical Society http://www.eriecountyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/strongvincent.pdf retrieved 9 June 2014

[6] Golay, Michael. To Gettysburg and Beyond: The Parallel Lives of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Edward Porter Alexander Crown Publishers Inc. New York 1994 p.129

[7] Nevins, James H. and Styple, William B. What Death More Glorious: A Biography of General Strong Vincent Belle Grove Publishing Company, Kearney NJ 1997 p.29

[8] Ibid Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.262

[9] Ibid. Nevins, What Death More Glorious p.54

[10] Leonardi, Ron Strong Vincent at Gettysburg in the Barringer-Erie Times News retrieved June 9th 2014 from http://history.goerie.com/2013/06/30/strong-vincent-at-gettysburg/

[11] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.55

[12] Wallace, Willard. The Soul of the Lion: A Biography of Joshua L. Chamberlain Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA 1960 p.91

[13] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.57

[14] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.264

[15] Pfanz, Harry F. Gettysburg: The Second Day. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1987 p.51

[16] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.159

[17] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.305

[18] Some such as Guelzo believe this may have been Captain William Jay of Sykes staff

[19] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.327

[20] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.262

[21] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.262

[22] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.327

[23] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.108

[24] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.389

[25] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.109

[26] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.390

[27] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.270

[28] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.75

[29] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.292

[30] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.109

[31] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.109

[32] Ibid. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day. p.213

[33] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.111

[34] Ibid. Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.157

[35] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.111

[36] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.52

[37] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top pp.44-45

[38] ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.52

[39] Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence Letter From Joshua L. Chamberlain to Governor [Israel] Washburn, Brunswick, July 14, 1862 retrieved from Bowdoin College, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Documents http://learn.bowdoin.edu/joshua-lawrence-chamberlain/documents/1862-07-14.html 8 November 2014

[40] Longacre, Edward Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man Combined Publishing Conshohocken PA 1999 p.39

[41] Ibid. Longacre, Edward Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.28

[42] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.30

[43] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.45

[44] Smith, Diane Monroe Fanny and Joshua: The Enigmatic Lives of France’s Caroline Adams and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Thomas Publications, Gettysburg PA 1999 p.120

[45] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.80

[46] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.66

[47] Ibid. Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.132

[48] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.66

[49] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.116

[50] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.45

[51] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.117

[52] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.94

[53] Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence. Official Narrative of Joshua Chamberlain of July 6th 1863, Maine Military Historical Society, Inc., Augusta, Maine, copyright 1989 U.S. Army Combat Studies Institute Reprint, retrieved from http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/cgsc/carl/download/csipubs/chamberlain.pdf June 15th 2014

[54] Oates, William C. and Haskell, Frank A. Gettysburg Bantam Books edition, New York 1992, originally published in 1905 p.98

[55] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.94

[56] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command p.393

[57] Ibid. Oates and Haskell Gettysburg p.87

[58] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.95

[59] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.272

[60] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.361

[61] LaFantasie, Glenn W. Twilight at Little Round Top: July 2, 1863 The Tide Turns at Gettysburg Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2005 pp.61-62

[62] Ibid. Jordan Happiness is Not My Companion: The Life of G.K. Warren p.93

[63] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.504

[64] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The Second Day p.228

[65] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The Second Day p.228

[66] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.153

[67] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.154

[68] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.327

[69] Ibid. Jordan Happiness is Not My Companion: The Life of G.K. Warren p.93

[70] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.294

[71] Wert, Jeffry D. A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2011 p.260

[72] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.207

[73] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.86

[74] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious pp.87-88

[75] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.115

[76] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion pp.134-135

[77] Ibid. Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.282

[78] Ibid. Smith Fanny and Joshua p.182

[79] Ibid. Smith, Fanny and Joshua p.180

[80] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.260

[81] Ibid. Smith, Fanny and Joshua pp.178-179

[82] Ibid. Smith, Fanny and Joshua p.181

[83] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.

[84] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.245

[85] Ibid. Smith, Fanny and Joshua p.180 It is interesting to note that Chamberlain’s commentary is directed at Northerners who were even just a few years after the war were glorifying Confederate leader’s exploits. Chamberlain instead directs the attention of his audience, and those covering the speech to the atrocities committed at the Fort Pillow massacre of 1864 and to the hellish conditions at the Andersonville and Belle Isle prisoner of war camps run by the Confederacy.

[86] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.203

[87] Ibid. Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.289

[88] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.259

[89] Ibid. Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.288

[90] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.285

[91] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.268

[92] Chamberlain, Joshua L. Letter Joshua L. Chamberlain to “Dear Fanny” [Fanny Chamberlain], Augusta, November 20, 1868 retrieved from Bowdoin College, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Documents http://learn.bowdoin.edu/joshua-lawrence-chamberlain/documents/1868-11-20.html 8 November 2014

[93] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.227

[94] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.297

[95] Ibid. Golay To Gettysburg and Beyond p.290

[96] Ibid. Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.290

[97] Ibid. Golay To Gettysburg and Beyond PPP.342-343

[98] Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence. Chamberlain’s Address at the dedication of the Maine Monuments at Gettysburg, October 3rd 1888 retrieved from http://www.joshualawrencechamberlain.com/maineatgettysburg.php 4 June 2014