Friends of Padre Steve’s World

I am continuing to periodically intersperse and publish short articles about various commanders at Gettysburg on the site. These all are drawn from my student text and may become a book in their own right. The reason is I am going to do this is because I have found that readers are often more drawn to the lives of people than they are events. As I have noted before that people matter, even deeply flawed people, and we can learn from them.

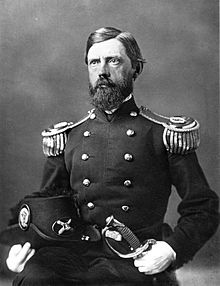

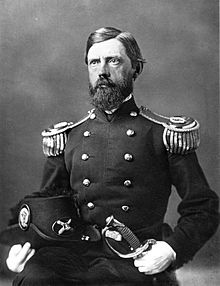

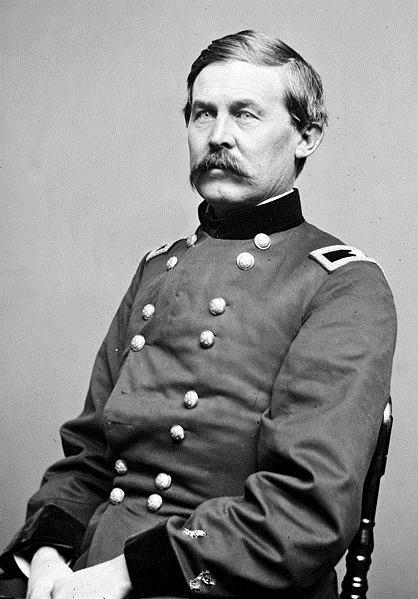

This article deals with Major General John Fulton Reynolds who in large part is responsible for bringing about the Battle of Gettysburg and whose actions on that field in the opening hours of the engagement helped decide the course of the Civil War. This segment does not include the details of that battle, those are reserved for the rest of this chapter which I am currently revising for the student text.

I have come to admire Reynold’s more and more and I hope that in this brief treatment of his life and career leading to Gettysburg that you will be inspired by his single dovotion to the Union and the humanity compassion that he treated the victims of war.

Peace

Padre Steve+

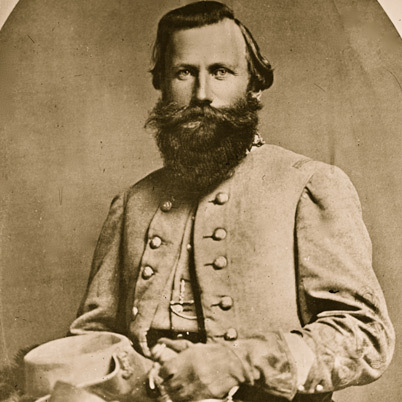

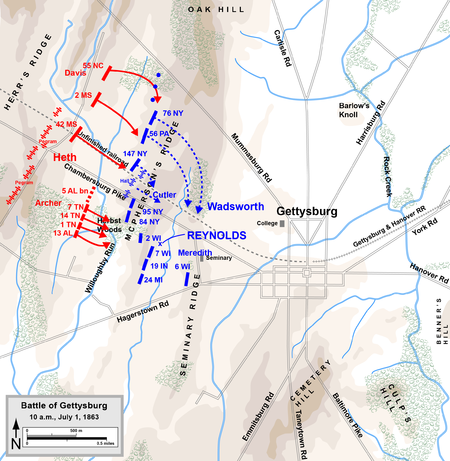

There is much written about the supposed superiority of Robert E. Lee and the generals of the Army of Northern Virginia over those of the Army of the Potomac. Their eventual defeat is often blamed on the Union’s superior manpower and attrition with scant recognition of times where the Union commanders, particularly at Gettysburg out-generaled them. Not only did Harry Heth have the misfortune of battling John Buford and John Reynolds, but division, brigade and regimental leaders who performed their duties magnificently. Despite being greatly outnumbered by the Confederates these men and their soldiers turned back the initial Confederate assaults and shattering Confederate infantry formations.

Likewise if chance plays a role in war, the Army of the Potomac had good fortune smiling upon it that fateful morning of July 1st 1863. Part of that good fortune was having Major General John Fulton Reynolds, one of the finest commanders on either side during the Civil War directing its operations. During the engagement Reynolds, his subordinates and his successor in command Abner Doubleday dealt with the unforeseen elements of this engagement far better than any Confederate General on the battlefield that morning. Reynolds exemplified the indispensable qualities described by Clausewitz regarding commanders who must deal with the role of chance and the unforeseen elements that so often cloud the battlefield:

“first, an intellect that, even in the darkest hour, retains the glimmerings of the inner light which leads to truth; and second, the courage to follow this faint inner light wherever it may lead.” [1]

John Reynolds was a native Pennsylvanian, born in Lancaster to descendants of Irish Protestants. His maternal grandfather, Samuel Moore fought as a Captain in the Continental Line during the American Revolution. Reynold’s father, was a lawyer and moved to Lancaster where he “owned and published the Journal.” The elder Reynolds had served two terms in the Pennsylvania legislature and in the early 1830s was a political ally and friend of Senator and later President James Buchannan for whom “he was attending to local business affairs” in Lancaster. [2] Buchannan helped one of Reynold’s brother William gain an appointment to the Naval Academy and in 1837 obtained the appointment to West Point.

The young Pennsylvanian graduated from West Point in 1841, twenty-sixth in a class of fifty-two and was commissioned as a Brevet Second Lieutenant in the artillery. Among his classmates were the future Union generals Israel Richardson, Don Carlos Buell and Horatio Wright and Confederate generals Richard Garnett and J.M. Jones. Graduating in the class ahead of him was a man who would become a lifelong friend, William Tecumseh Sherman. He graduated at a time of military cutbacks, the Army was about to be reduced from 12,000 to 9,000 the following year. Chances for promotion were so bad, especially from First Lieutenant to Captain, “so unlikely that in a single year 117 officers resigned.” [3] Many of these officers would find their way back to the army but even so, army life did not promise much.

Despite this Reynolds found army life to his liking. He served in Florida during the Seminole War, as well as in Mexico “where he was cited for bravery at Monterey and Buena Vista.” [4] During the campaign in Mexico he served with the army commanded by General Zachary Taylor and in the artillery battery commanded by the future Confederate general, Captain Braxton Bragg. He acquitted himself well and also had compassion for the Mexican soldiers that he fought against. Visiting Mexican wounded who had been left with “little medical care and less food” he gave them money to help with their needs. At Buena Vista a number of senior officers wrote official citations praising the artillery and Reynolds by name. General John Wool wrote

“Without our artillery,” he said, “we could not have maintained our position a single hour,” and also: “…a section of artillery, admirably served by Lieutenant Reynolds, 3rd Arty, played an important part in checking and dispersing the enemy in the rear of our left. They retired before him whenever he approached them.” [5]

Those actions brought him fame and two brevet promotions for bravery, [6] to Captain at Monterrey and Major at Buena Vista. However, Reynolds saw little value in them if the army’s promotion system was not fixed. He wrote his brother Jim “The system is a complete humbug and until it changes I believe it is to be rather more of a distinction to be passed over than to be breveted…that is, amongst us who know facts.” [7]

Reynold’s skill as an artilleryman would be used to great effect on the morning of July 1st 1863 on McPherson’s Ridge at Gettysburg. Following the war he remained in the army predominantly with the artillery. He served in field and coastal batteries and like John Buford had “participated in the Utah Expedition.” [8] The Utah expedition is little known and nearly forgotten incidents in United States history which involved the territory of Utah, and it left a bitter taste in the mouths of many of the officers and soldiers who served in it, including John Reynolds.

The Territory of Utah had been created after the Compromise of 1850 and President Millard Fillmore named Mormon leader Brigham Young as Governor. The Mormons settled Utah after having been driven out of Illinois and Missouri as a result of their religious beliefs which included polygamy and well as the political concept Theodemocracy, which had been formulated by Mormon founder Joseph Smith Jr. Theodemocracy was a concept which is a blend of theocracy and republican principles. Though it largely died out after the replacement of Young as Governor it has many similarities with theology, political ideology and goals of the leaders of the current Christian Dominion concepts of the leaders of what is called The New Apostolic Reformation which has gained much power among the leadership of the current Republican Party.

In Illinois Smith had “founded an autonomous community, with its own militia, where Smith was eventually called “King of the Kingdom of God.” [9] Smith believed that it was a necessary step until a true theocracy could be established. Smith had taught his ruling Council of Fifty, which included a few non-Mormons “that in the initial stages of the millennium the council would participate in concert with men of differing religious and political persuasions” and the earth would still have a pluralism of governments and religions in the early part of those thousand years…” [10] Tensions between Smith, the Mormon community and surrounding communities grew and “eventually, an unruly mob lynched the prophet and one of his followers.” [11]

Two years after the territory was formed Young “declared that Smith had a vision, until then kept secret, reinstituting polygamy.” [12] To be fair, Young did not require this of his followers, but the introduction produced a furor among many Americans. The situation with Utah was complicated further by the actions of Congress which in throwing out the Missouri Compromise that Utah and New Mexico “when admitted as a State or States…shall be received into the Union, with or without slavery, as their constitution may prescribe at the time of their admission.” [13]

The combination of a growing theocracy, the introduction of polygamy and the possibility of slavery brought many tensions. The 1856 convention of the new Republican Party condemned “the twin relics of barbarism” – slavery and polygamy.” Midwesterners who joined that part remembered their clashes with the Mormons and “few voters were sympathetic to the Mormons” [14] or their growing power in the Utah Territory. In 1857 this tension led to President James Buchannan to appoint a non-Mormon Governor for the territory which led to conflict between Young’s government and its militias and the United States. Young considered U.S. Troops to be those of a “foreign power” and prepared for war “insisting as strongly on the independence of his people from Washington as the capital insisted on its jurisdiction over the territory.” [15]

Like many officers and Americans in general, Reynolds had negative views of the Latter Day Saints. Some were gained in his introduction to the territory, where he found that as a “gentile” he was treated as an outsider by the Mormon community. His initial bad disposition was only deepened through his interactions with Governor Brigham Young. The most important of these to Reynolds was an attempt to bring to justice the Indians who had massacred a party of army engineers under the command of Captain Gunnison the previous summer. Reynolds for that the Mormon led government, particularly Governor Young had convicted the Indians of manslaughter and sentenced them to prison for manslaughter. This act angered Reynolds. He wrote his sisters:

“They have been since tried by the Mormons and found guilty of manslaughter, tho’ the proof was positive and clear. But their jury was counseled by Brigham Young as to their verdict and perjured themselves. May God have mercy upon them, they would hang two Indians for killing two Mormon boys last summer when there was scarcely any proof at all, but when a Gentile is murdered it is only manslaughter!! I cannot write the truth about these people here – but will sometime later.” [16]

After Utah Reynolds served in Kansas and briefly in the Pacific Northwest. During that time he developed a dislike for radical abolitionists who he believed were responsible for much of the division of the country.

But with tensions growing in 1860 Reynolds was appointed as Commandant of the Corps of Cadets at West Point. During the interregnum of the election of Abraham Lincoln and his inauguration he “hoped for a moderate course that might avoid war.” [17] However, the Confederate seizure of U.S. facilities and siege of Fort Sumter and the tensions building between Southerners and Northerners at the Academy weighed on Reynolds and soon brought about a break with his family’s longtime political ally and benefactor President James Buchannan. Though normally not outspoken about his political beliefs on thing was sure, he valued the Union and as with the Mormons opposed those who sought to undermine it. He wrote his sister Ellie about his feelings for the President at his administration:

“What will history say of us, our Government, and Mr. B’s Administration makes one wish to disown him….”I have said but little, except among ourselves here, on the present difficulties that surround the Government but a more disgraceful plot, on the part of our friend B’s cabinet and the leading politicians of the South, to break up our Government, without cause, has never blackened the pages of history in any nation’s record.” [18]

However, Reynolds’s harshest and most bitter words were reserved for Jefferson Davis who he had served with in Mexico:

“…Who would have believed that when I came here last September and found Mr. Jeff Davis laboring with a Committee of Congress and civilians to re-organize the Academy; our national school! Whose sons, never until the seeds sown by his parricidal hand had filled it with the poisonous weed of secession, had known any other allegiance than the one to the whole country, or worshipped any other flag, than that which has moved our own youthful hopes and aspirations and under which we marched so proudly in our boyish days – who! I dare say, would have believed, that he was brooding over his systematic plans for disorganizing the whole country. The depth of his treachery has not been plumbed yet, but it will be.” [19]

Reynolds served at the Academy until June of 1861 when it graduated its final class before the war began. Departing West Point he was initially appointed as Lieutenant Colonel of the 14th U.S. Infantry regiment. [20] He would have preferred the artillery but wrote that he “could not refuse this promotion offered me under any circumstances, much less at this time, when the Government has a right to my services in any capacity.” [21] How much different was Reynolds than another politically moderate and illustrious soldier, Robert E. Lee, who barely a month after accepting a promotion to full Colonel in the Regular Army resigned his commission to serve his state of Virginia and the Confederacy rather than lead an army “in an invasion of the Southern States” whatever Virginia decided.” [22]

Before Reynolds could take command of the 14th United States, he was promoted to Brigadier General. He commanded a brigade of Pennsylvania volunteers during the Peninsula Campaign and was captured on June 28th after leading his troops successful at Gaines Mill, as McClellan began his withdraw from the gates of Richmond. He spent six weeks in Confederate captivity but was released in a general prisoner exchange on August 15th 1862. [23] Despite being captured Reynolds’s performance during the Seven Days was praised by friend and foe alike and even his Confederate enemies in the city of Fredericksburg petitioned Richmond to release Reynolds who they said:

“when inasmuch as we were prisoners in the hands of General Reynolds we received from him a treatment distinguished by a marked and considerable respect for our opinions and feelings, it becomes us to use our feeble influence in invoking for him, now a prisoner of our Government as kind and as considerate as was extended by him to us. We would therefore hope that he might be placed on parole…” [24]

In doing so they returned to the Army of the Potomac the man who would help decide the fate of the Confederacy barely ten months later.

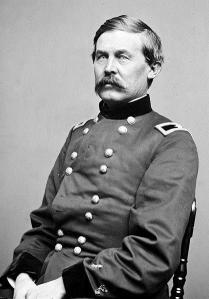

Reynolds returned to command a division at Second Bull Run where his division held firm as much of the army retreated. Reynolds missed the battle of Antietam as he was called to “the fruitless and frustrating task of trying to organize Pennsylvania’s militia” [25] by Governor Curtin. He returned to the Army of the Potomac and again commanded First Corps at Fredericksburg and again at Chancellorsville.

Reynolds was reportedly offered command of the Army of the Potomac by Lincoln in early June of 1863 but declined it. He went to the White House when he heard that he was under consideration for the post and ensured that he would not get the job by stating the his conditions for taking it. However, he did “urge the president to appoint Meade in Hooker’s place.” [26] He told his artillery chief Colonel Wainwright that he “refused it because he would have been under the same constraints as Burnside and Hooker.” [27] Colonel Wainwright believed that it was in large part due to “Reynolds’s recommendation that General Meade received his appointment.” [28]

The Army of the Potomac’s senior leadership had been the source of much political consternation during 1862 and 1863 for Abraham Lincoln. It was split among Lincoln’s supporters and detractors, Radical Republican abolitionists and moderate Democrats. To complicate matters some of senior leaders of the Army of the Potomac including McClellan, Hooker and Sickles had their own, scarcely hidden aspirations for the presidency.

However, Reynolds was of a different character than the politically connected and conniving commanders who used their position in the army to advance their career. Reynolds was a moderate Pennsylvania Democrat and prior to the war had been no supporter of Lincoln, once comparing him to a “baboon.” That opinion being noted, Reynolds did not allow his political beliefs and opinions to influence the manner in which he upheld his oath to the nation in time of civil war. Lincoln was President and was attempting to hold the Union together against forces that Reynolds found decidedly treacherous. It was a tribute to Reynold’s personal manner of keeping politics out of his command, which allowed him, a moderate Democrat to successfully command a corps whose divisions “were commanded by some of the Army’s most fervent abolitionists – Abner Doubleday, James S. Wadsworth, and John Cleveland Robinson.” [29]

Reynolds was “a serious unbending professional, who unlike McClellan, actually lived by the principle of “obedience to the powers that be.” [30] The Pennsylvanian was “universally respected” in the army “for his high character and sterling generalship” [31] it was noted that unlike others who so quickly interjected themselves into the political turmoil which had embroiled the nation that Reynolds had a policy of holding back. He stood “stoutly aloof from all personal or partisan quarrels, and keeping guardedly free from any of the heart-burnings and jealousies that did so much to cripple the usefulness and endanger the reputation of many gallant officers.” [32]

Oliver Howard noted that unlike many commanders that Reynolds was a commander “who had a steady hand in governing, were generous to a fault, quick to recognize merit, trusted you and sought to gain your confidence, and, as one would anticipate, were the foremost in battle.” [33] George McClellan noted that Reynolds was “remarkably brave and intelligent, an honest, true gentleman.” [34] In his autobiography Howard wrote about Reynolds:

“From soldiers, cadets, and officers, junior and senior, he always secured reverence for his serious character, respect for his ability, care for his uniform discipline, admiration for his fearlessness, and love for his unfailing generosity.” [35]

On the night of June 30th Reynolds was awash in reports, some of them conflicting and even though he was without Meade’s course of action for the next day “concluded that Lee’s army was close by and in force.” [36] He spent the night at his headquarters “studying the military situation with Howard and keeping in touch with army headquarters.” [37] Howard noted Reynolds anxiety and “received the impression that Reynolds was depressed.” [38] After Howard’s departure Reynolds took the opportunity to get a few hours of fitful sleep before arising again at 4 a.m. on July 1st.

When morning came, Reynolds was awakened by his aide Major William Riddle with Meade’s order to “advance the First and Eleventh Corps to Gettysburg.” [39] Reynolds studied the order and though he expected no battle that morning, expecting “only moving up to be in supporting distance to Buford” [40] took the prudent and reasonable precautions that his Confederate opponents A.P. Hill and Harry Heth refused to take as they prepared to move on Gettysburg.

His troops were in fine spirits that morning even though it had been busy. After a breakfast of hardtack, pork and coffee the troops moved out. An officer of the Iron Brigade noted that the soldiers of that brigade were “all in the highest spirits” while Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Dawes of the “placed the fifes and drums at the head of the Sixth Wisconsin and ordered the colors unfurled” as the proud veterans marched forward into the sound of the raging battle to the tune of “The Campbell’s are Coming.” [41]

Though Reynolds was not expecting a fight he organized his march in a manner that ensured if one did happen that he was fully prepared. The precautionary measures that he took were those that any prudent commander having knowledge that strong enemy forces were nearby would take. Reynolds certainly took to heart the words of Napoleon who said “A General should say to himself many times a day: If the hostile army were to make its appearance in front, on my right, or on my left, what should I do?” [42]

This was a question that A.P. Hill and Harry Heth seemed not to consider on that warm and muggy July morning when Heth was committing Lee’s army to battle on his own authority. Reynolds was also about to commit the Army of the Potomac to battle, but unlike Heth who had no authority to do so, Reynolds “had at least been delegated the authority for making such a decision.” [43] While Meade was unaware of what was transpiring in the hills beyond Gettysburg he implicitly trusted the judgement of Reynolds, and he been with the advanced elements of Reynold’s wing Meade too “probably would have endorsed any decision he made.” [44]

Reynolds placed himself with the lead division, that of Wadsworth, and “had directed Doubleday to bring up the other divisions and guns of the First Corps and had ordered Howard’s Eleventh Corps up from Emmitsburg.” [45] Reynold’s also understood the urgency of the situation and “wanted all the fighting troops to be up front, so he instructed Howard not to intermingle his supply wagons with his infantry. Similar instructions had been given to Abner Doubleday; to ensure that the First Corps wagons would wait until the Eleventh Corps foot soldiers had passed.” [46]

Instead operating in the normal fashion of rotating units on the march, Reynolds opted to save time. Since the First Division under the command of James Wadsworth was further advanced than other I Corps divisions, Reynolds instructed it to move first with Cutler’s brigade in the lead followed by the Iron Brigade under Colonel Solomon Meredith. In doing so he countermanded the order of the acting corps commander Doubleday who had ordered that division to allow the other divisions of First Corps to pass his before advancing. Reynolds told Wadsworth that Doubleday’s order “was a mistake and that I should move on directly.” [47]

He went forward with Wadsworth’s division and gave Doubleday his orders for the coming engagement. Doubleday later recalled that when Reynolds arrived to discuss the situation that Reynolds:

“read to me the various dispatches he had received from Meade and Buford, and told me that he should go at once forward with the leading division – that of Wadsworth – to aid the cavalry. He then instructed me to draw in my pickets, assemble the artillery and the remainder of the corps and join him as soon as possible. Having given me these orders, he rode off at the head of the column, and I never saw him again.” [48]

Reynolds ordered Howard’s XI Corps to follow and according to Doubleday directed an aid of Howard to have Howard “bring his corps forward at once and form them on Cemetery Hill as a reserve.” [49] While some writers that he directed Oliver Howard to prepare Cemetery Hill as a fallback position [50] there is more evidence that points to Howard selecting the that commanding hill himself. [51]

Likewise Reynolds ordered Sickles’ III Corps to come up from Emmitsburg where that corps had bivouacked the previous night. [52] Sickles had heard the guns in the distance that morning and sent his senior aide, Major Henry Tremain to find Reynolds. Reynolds told Tremain “Tell General Sickles I think he had better come up” but the order left Sickles in a quandary. He recalled “he spend an anxious hour deciding what to do” [53] for he had “been ordered by Meade to hold his position at Emmitsburg” [54] and Sickles sent another rider to Reynolds and awaited the response of his wing commander instead of immediately advancing to battle on 1 July and it would not be until after 3 P.M. that he would send his lead division to Gettysburg.

Reynolds’ intention according to Doubleday was “to fight the enemy as soon as I could meet him.” [55] Reynolds rode forward with some of his staff into the town as the infantry of I Corps and XI Corps moved advanced. In the town they were met by “a fleeing, badly frightened civilian, who gasped out the news that the cavalry was in a fight.” [56] When he came to the Lutheran Seminary he came across Buford. It was a defining moment of the Civil War, a moment that shaped the battle to come. It has been recounted many times and immortalized on screen in the movie Gettysburg, a time “when the entire battle would come down to a matter of minutes getting one place to another.” [57]

As the rough and tumble Kentuckian, Buford, and Reynolds, the dashing Pennsylvanian, discussed the situation they had to know that odd that they were facing. With close to 32,000 rebels from the four divisions of Hill’s and Ewell’s corps closing in from the west and the north with only about 18,000 men of First Corps, Eleventh Corps and Buford’s cavalry division the odds did not favor them, but unlike other battles that the army of the Potomac faced, this time the army and its commanders were determined not to lose and not to retreat.

Reynolds and Buford committed their eighteen thousand men against Lee’s thirty-two thousand in a meeting engagement that develop into a battle that would decide the outcome of Lee’s invasion. Likewise it was a battle for the very existence of the Union. Abner Doubleday noted the incontestable and eternal significance of the encounter to which Buford and Reynolds were committing the Army of the Potomac:

“The two armies about to contest on the perilous ridges of Gettysburg the possession of the Northern States, and the ultimate triumph of freedom or slavery….” [58]

Notes

[1] Ibid. Clausewitz On War p.102

[2] Nichols, Edward J. Toward Gettysburg: A Biography of John Fulton Reynolds Pennsylvania State University Press, Philadelphia 1958. Reprinted by Old Soldier Books, Gaithersburg MD 1987 p.4

[3] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.13

[4] Tagg, Larry The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle Da Capo Press Cambridge MA 1998 Amazon Kindle Edition p.10

[5] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg pp.43-44

[6] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001pp.47-48

[7] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.46

[8] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[9] Gonzalez, Justo L. The History of Christianity Volume 2: The Reformation to the Present Day Harper and Row Publishers San Francisco 1985 p.259

[10] Ehat, Andrew” It Seems Like Heaven Began on Earth”: Joseph Smith and the Constitution of the Kingdom of God in BYU Studies Vol 20. No 3 1980) retrieved from https://ojs.lib.byu.edu/spc/index.php/BYUStudies/article/view/5144/4794 20 May 2015 p.258

[11] Ibid. Gonzales p.259

[12] Ibid. Gonzales p.259

[13] Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis: America before the Civil War 1848-1861 completed and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher Harper Collins Publishers, New York 1976 p.158

[14] Goldfield, David. America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation Bloomsbury Press, New York 2011 p.122

[15] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.58

[16] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.58

[17] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.73

[18] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.73

[19] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.73

[20] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[21] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.75

[22] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.228

[23] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume One Fort Sumter to Perryville Random House, New York 1958 p.493

[24] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.100

[25] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[26] Sears, Stephen W. Controversies and Commanders Mariner Books, Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1999 p.162

[27] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 pp. 40-42

[28] Nevins. Allan editor. A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles Wainwright 1861-1865 with an introduction by Stephen W. Sears Da Capo Press, New York 1998 p.229

[29] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.30

[30] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.29-30

[31] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 34

[32] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.30

[33] Howard, Oliver O. Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General, U.S. Army Volume 1 The Baker and Taylor Company, New York 1907 Made available by the Internet Achieve through Amazon Kindle location 5908 of 9221

[34] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.101

[35] Ibid. Howard Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard location 5908 of 9221

[36] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[37] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command p.261

[38] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[39] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.261

[40] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 158

[41] Nolan, Alan T. The Iron Brigade: A Military History Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN, 1961 and 1994 pp.233-234

[42] Napoleon Bonaparte, Military Maxims of Napoleon in Roots of Strategy: The Five Greatest Military Classics of All Time edited by Phillips, Thomas R Stackpole Books Mechanicsburg PA 1985 p.410

[43] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 165

[44] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.49

[45] Ibid. Nolan The Iron Brigade p.233

[46] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.159

[47] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.156

[48] Doubleday, Abner Chancellorsville and Gettysburg: Campaigns of the Civil War VI Charles Scribner’s Sons, Bew York 1882 pp.70-71

[49] Ibid. Doubleday Chancellorsville and Gettysburg p.71

[50] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.76

[51] Green, A. Wilson. From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p. 70

[52] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 158

[53] Keneally, Thomas American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil war General Dan Sickles Anchor Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2003 p.275

[54] Swanberg, W.A. Sickles the Incredible Copyright by the author 1958 and 1984 Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA 1991 p.202

[55] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.156

[56] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 165

[57] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.142

[58] Ibid. Doubleday Chancellorsville and Gettysburg p.68