Friends of Padre Steve’s World

This is the third part of my re-written chapter on the leadership of Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg. Today is a look at the leaders of Lieutenant General Richard S. “Dick” Ewell’s Second Corps. This like the following sections of this chapter of my Gettysburg text is interesting because it shows the complexities of the lives and personalities of the men leading these units. Professional soldiers, volunteers with little military experience, soldiers, lawyers, engineers and politicians they are an interesting collection of personalities; some surrounded in myth and others practically unknown. I think it is important for anyone studying a war, a campaign, or a battle to at least look at the lives of the men who planned and fought it. In doing so, even those that oppose what they did in rebelling against the United States can find in them some measure of humanity, and sometimes even gain a sense of empathy for some of them.

That is why when we look at the lives of soldiers, we have to take the time to at least try to understand the nuance, the contradictions, their strengths and weaknesses as leaders, as well as a measure of their character.

In the coming week I will be doing A.P. Hill’s Third Corps, and Stuart’s Cavalry Division. I will then get to work on a similar chapter for the Army of the Potomac.

Have a great night

Peace

Padre Steve+

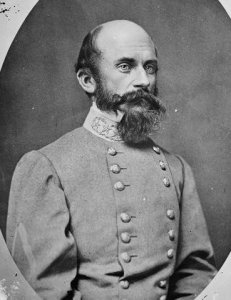

Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell C.S.A.

Since Lee believed that the size of his two corps was too ponderous, especially for those that he was considering as successors to Jackson, Lee divided Jackson’s old Second Corps into tow elements. To command the three division that now comprised the Second Corps, Lee promoted Major General Richard Ewell to Lieutenant General.

Dick Ewell was a modest man and “had maintained a reputation for solid competence.” [1] Freeman wrote:

“In part, the appointment of Dick Ewell was made because of sentimental association with the name Jackson, and in part because of admiration for his unique, picturesque, and wholly lovable personality. Of his ability to lead a corps nothing was known. Ewell had never handled more than a division and he had served with Lee directly for less than a month.” [2]

Ewell was native of Virginia, his father, Thomas Ewell, was a physician and scientific writer whose works created controversy with both the Catholic and Episcopal Churches. Though a gifted writer and editor his finances declined even as the size of his family increased, plunging the family into poverty. The elder Ewell struggled with depression and alcoholism and died at the age of forty in in 1826 when Richard was nine years old. Ewell’s maternal grandfather was Benjamin Stoddert who served in the Revolutionary war and as the first Secretary of the Navy by John Adams. Stoddert helped create the Navy that rose to greatness. “In just three years he purchased land for six navy yards, acquired fifty ships, and recruited 6,000 sailors, including a corps of talented young officers that included David Porter, Isaac Hull, Oliver Perry, and Stephen Decatur.” [3]

When his father died the family remained in poverty on the family farm, albeit poverty with a distinguished heritage which his mother ensured that her children understood. She also instilled a strict religious faith in her son. With one brother at West Point and another having died of a liver infection, possibly caused by typhoid, Richard took over the management of the family farm. His mother, who sought more than a rudimentary education for him worked to get him an appointment to West Point for several years and he was finally admitted to the academy in 1836. Ewell was an eccentric, in many ways like his father, mother and grandfather:

“In him one could see the practical, precise mind of his grandfather Benjamin Stoddert and, negatively, the cynicism and sharp tongue of his mother, Elizabeth. The similarities to his deceased father were more pronounced. Richard possessed Thomas Ewell’s violent temper, high intellect, nervous energy, and love of alcohol.” [4]

In 1836 Ewell entered West Point, from which he graduated in 1840 along with his classmates, William Tecumseh Sherman and George Thomas. Some of his seniors in his cadet company included Joseph Hooker, John Sedgwick, P.T.G. Beauregard, Henry Halleck, Jubal Early and Henry Hunt, all of whom served as General officers in either the Union or Confederate armies during the Civil War. Some of the underclassmen who served under him included both James Longstreet and Ulysses S. Grant. By the end of his time at West Point Ewell had “developed into not only an impressive student but an impressive soldier.” [5] He graduated thirteenth in a class of forty-two and chose to be commissioned in the Dragoons.

Upon graduation and his brevet promotion to Second Lieutenant the young officer reported to the First Dragoons and served on the western territories and plains of the rapidly expanding nation. Ewell was picky as far as relationships went and seeing the often sad examples of men who married on the frontier he elected to wait, which caused him not to marry until after the Civil War began.

On the frontier his Christian faith began to wane. He still believed in God, but he was a skeptic, did not own a Bible and found little solace in region, even as his mother converted to Catholicism and entered a novitiate with a Catholic religious order. His antipathy was deepened as he observed the behavior of Christian missionaries working among the various Indian tribes. Of the missionaries he observed “wife beating, fornication, theft and adultery.” He was taken by surprise when his younger brother William decided to become a missionary. Ewell wrote: “I have seen so much injury done the Indians here by them that I am rather skeptic[c]al of their utility. Some of the greatest scamps we have are missionaries.” [6] Despite this he never completely lost faith. Stonewall Jackson had a marked influence on his return to faith. One night before a battle he heard Jackson praying inside his tent and later remarked that “he had never before heard a prayer so devout and beautiful; he then for the first time, felt the desire to be a Christian.” [7]

When war came with Mexico Ewell, now a First Lieutenant went with his company. He fought at Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Puebla and Churubusco. While he suffered no physical harm in combat, he developed malaria and he lost his older brother Tom, who was serving with the Mounted Rifles and was mortally wounded at Cerro Gordo, and his cousin Levi Gannt, was killed at Chapultepec. Following Mexico he served in various duties became a noted Indian fighter on the western frontier. Those duties showed that “he had proved his mettle and established his credibility.” [8]

As secession drew near Ewell was very sick again with fever and was being returned to Virginia, some thought to die. However, that did not stop him from offering to fight a group of secessionists in Texas who were threatening to attack a Federal installation. He returned to health and on April 24th 1861 he resigned his commission in the U.S. Army, an act that he wrote “was like death to me.” [9] He was commissioned in the new Confederate Army as a Lieutenant Colonel of Cavalry shortly after his resignation.

Completely bald, and speaking with a lisp, Ewell’s oddities “endeared him to his officers and men,” [10] and by January 1862 he was a division commander and Major General serving under Jackson in the Valley campaign. John Gordon noted that Ewell “had in many respects the most unique personality I have ever known. He was composed of anomalies, the oddest, most eccentric genius in the Confederate Army….” [11] During that campaign he distinguished himself. During the campaign “Next to Jackson himself, Ewell stood out. Every act of Ewell’s in the campaign had been the standard of a competent, alert, and courageous lieutenant.” [12]

William C. Oates wrote of Ewell:

“Ewell was a first-class lieutenant, but he did not have enough confidence in himself to make him successful with an independent command…He hesitated…Therein was Ewell’s deficiency as a general. He had a splendid tactical eye, capable of grand military conceptions, and once resolved quick as lightening to act, yet never quite confident of his own judgment and sought the approval of others before he would execute.” [13]

Ewell had been an effective and dependable division commander under Jackson but had been wounded at Groveton where he was severely wounded and lost a leg, which meant the “absence for long months of the most generous, best disciplined, and in many soldierly qualities, the ablest of Jackson’s subordinates.” [14] Longstreet “regarded him as a superior officer in every respect to Hill.” [15]However, Ewell, though serving long with Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley had served “only briefly under Lee” [16] before being wounded at Groveton. The result was that neither Lee nor Ewell fully knew or understood each other. Lee knew Ewell’s excellent reputation among the soldiers of Second Corps and “may have heard rumors that on his deathbed Jackson expressed a preference for Ewell as his successor” [17] but he had little familiarity with Ewell.

In sending the recommendation on to Richmond Lee termed Ewell “an honest, brave soldier, who has always done his duty well.” [18] It was not a resounding recommendation, but then Lee barely knew Ewell. Lee wrote after the war that he recommended Ewell “with full knowledge of “his faults as a military leader- his quick alternations from elation to despondency[,] his want of decision &c.” [19] Many questions hovered around the appointment of Ewell including how the loss of his leg, his recent marriage, newness to corps command, and unfamiliarity with Lee’s style of command would have on him.

The latter was even more problematic than any residual mental or physical effects of his wound and change in lifestyle. The fact was that Ewell was unfamiliar with Lee’s methods of command in large part because he “had served directly under Lee something less than a month, and then always subject to Jackson’s guidance. Lee never had an opportunity of the lack of self-confidence in Ewell.” [20] Had Lee known that the humble Ewell had reservations of his own about assuming command of a corps and going back to battle after the traumatic amputation of his leg, he had written “I don’t feel up to a separate command” and he had “no desire to see the carnage and shocking sights of another field of battle.” [21] Ewell admitted to his new bride Lizinka that he was “provoked excessively with myself at times at my depression of spirits & dismal way of looking at everything, present & future….” [22] Lee did speak privately about his concerns to Ewell, but no record exists of the conversation, regardless Lee was not concerned enough to remove Ewell from command or to assign his corps to important tasks.

Ewell’s reorganized Second Corps now consisted of his former division, commanded since Antietam by Major General Jubal Early, who in some measure acted as Ewell’s executive officer, on whom “Ewell came to rely on heavily – perhaps too heavily – on his judgment.” [23] The corps also contained the former division of Stonewall Jackson under the command of Edward “Old Allegheny” Johnson, an old regular with a solid record of service. The former division of D.H. Hill was now under the command of Robert Rodes, a VMI graduate and professor who had never served in the Regular Army and only had briefly commanded a division before his appointment to command. The brigade level commanders in the corps were another matter.

Early’s Division

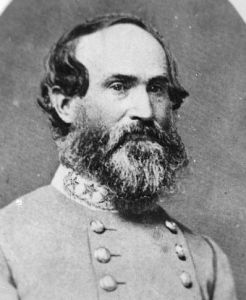

Major General Jubal Early C.S.A.

Early was an unusual character. Described similarly by many to Ewell in his gruffness and eccentrics, unlike Ewell, who was modest and charitable, Early was “ambitious, critical, and outspoken to the point of insubordination. Under certain circumstances he could be devious and malevolent.” [24] Longstreet’s aide Moxey Sorrel wrote of him: “Jubal Early….was one of the ablest soldiers in the army. Intellectually he was perhaps the peer of the best for strategic combinations, but he lacked the ability to handle troops effectively in the field….His irritable disposition and biting tongue made him anything but popular.” [25] Despite this, Early had proved himself as a brigade commander and acting division commander and Lee referred to him affectionately as “my bad old man.” [26]

Early was the son of a tobacco planter in Franklin County Virginia who had served in the Virginia legislature and was a Colonel of militia. Growing up he had an aptitude for science and mathematics accepted into West Point in 1833 at the age of seventeen. His fellow students included Joe Hooker, John Sedgwick, Braxton Bragg, and John Pemberton, later, the doomed defender of Vicksburg. Also in the class was Lewis Armistead, with whom the young Early, had an altercation that led to Armistead breaking a plate over his head in the mess hall. For the offense Armistead was dismissed from the academy. Early was a good student, but had poor marks for conduct and graduated eighteenth in a class of fifty.

He was commissioned into the artillery on graduation in 1837. However, after experiencing life in the active duty army, including service in the in the Seminole War, left the army and became a highly successful lawyer and active Whig politician. He served in the Mexican war as a Major with Virginia volunteers. Unlike some of his classmates, and later contemporaries in the Civil War, Early, and his men did not see combat, and instead served on occupation duty. In Mexico Zachary Taylor made Early the “military governor of Monterrey, a post that he relished and filled with distinction.” [27]

After his service in Mexico Early returned to Virginia where he returned to his legal practice, served as a prosecuting attorney and to politics where he served as a Whig in the Virginia legislature.

During his time in Mexico contracted rheumatic fever, which left him with painful rheumatoid arthritis for the rest of his life. Due to it he “stooped badly and seemed so much older than his years that his soldiers promptly dubbed him “Old Jube” or Old Jubilee.” [28]

Jubal Early was “notoriously a bachelor and at heart a lonely man.” Unlike many Confederate officers he had “no powerful family connections, and by a somewhat bitter tongue and rasping wit” isolated himself from his peers.[29]

Likewise, in an army dominated by those with deep religious convictions, Early was avowedly irreligious and profane, though he did understand the importance of “the value of religion in keeping his soldiers’ spirits up” and as commander of the Army of the Valley issued orders for a stricter keeping of the Sabbath. [30] Lee’s adjutant Walter Taylor wrote of him “I feared our friend Early wd not accomplish much because he is such a Godless man. He is a man who utterly sets at defiance all moral laws & such a one heaven cannot favor.” [31] That being said Porter Alexander praised Early and noted that his “greatest quality perhaps was the fearlessness with which he fought against all odds & discouragements.” [32]

Early was a Whig, and a stalwart Unionist who opposed Virginia’s secession voting against it because he found it “exceedingly difficult to surrender the attachment of a lifetime to that Union which…I have been accustomed to look upon (in the language of Washington) as the palladium of the political safety and prosperity of the country.” [33] Nonetheless, like so many others he volunteered for service after Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to crush the rebellion.

Lee “appreciated Early’s talents as a soldier and displayed personal fondness for his cantankerous and profane Lieutenant …who .Only Stonewall Jackson received more difficult assignments from Lee.” [34] He was the most influential of Ewell’s commanders, and his “record in battle prior to Gettysburg was unsurpassed.” [35]

Early’s brigade commanders included standouts such as Brigadier General John Gordon and Harry Hays, which was balanced out by the weakness of Brigadier General William “Extra Billy” Smith and the inexperience of Colonel Isaac Avery, who commanded the brigade of Robert Hoke who had been wounded at Chancellorsville.

Gordon

Brigadier General John Gordon was one of the most outstanding Confederate commanders in the Civil War, eventually rose to command Second Corps. He is possessed of a naturally chivalrous character, which would be show on the Gettysburg battlefield where he came to the aid of the wounded Union General Francis Barlow. Though lacking in some highest command abilities due to his inexperience, he brings a certain freshness, boldness, freedom and originality to command. At Appomattox he was detailed to lead the remnants of the Army of Northern Virginia as it formally surrendered, the officer receiving the surrender was Major General Joshua Chamberlain, who honored the defeated Rebel army by bringing his division to present arms.

Gordon was not a professional soldier, he raised a company from the northwest corner of Georgia called “the Raccoon Roughs” in the opening weeks of the war.” [36] Georgia had no room in its new military for the company and Gordon offered it to Alabama. After Manassas was elected colonel of the 6th Alabama which he commanded the regiment until he was wounded five times in the defense of the Bloody Lane at Antietam. Though he had no prior military experience he learned his trade well and possessed “an oratorical skill which inspires his troops to undertake anything. His men adore him….he makes them feel as if they can charge hell itself.” [37] He is promoted to Brigadier General Gordon took command of Lawton’s brigade of Georgians prior to Chancellorsville.

Hays

Brigadier General Harry Hays was a New Orleans lawyer who had served as “lieutenant and quartermaster of the 5th Louisiana in the Mexican War” and “When the South seceded Hays was made colonel of the 7th Louisiana.” [38] Harry Hays was a solid commander who was promoted to command a Louisiana brigade before the 1862 Maryland campaign. He would continue to serve with distinction until he was wounded at Spotsylvania.

“Extra Billy” Smith

Brigadier General William “Extra Billy” Smith was a sixty-five year old politician turned soldier who was a “valiant but unmilitary officer.” [39] He refused an appointment as a brigadier from Governor John Letcher of Virginia, because “he was wholly ignorant of drill and tactics,” [40] but he instead accepted an appointment as Colonel of the 49th Virginia, and attempted to learn the trade of being a soldier, though he never gave up his political office, serving in the Confederate Congress while at the same time serving as the Colonel of the 49th Virginia. Smith’s case was certainly an unusual, even in an unusual army.

Though never much of a tactician, he was brave in battle. He commanded that regiment and was acting commander of Early’s brigade at Antietam, where he was wounded three times, but directed his troops until the battle was over. Jeb Stuart observed him during the battle “dripping blood but fighting gallantly.” [41] Smith was “the only political general to survive Lee’s weeding out” [42] of officers after Chancellorsville, and in “commanding a brigade Extra Billy Smith was straining the limits of his martial abilities.” [43] He left the army in 1864, but only after he had been elected Governor of Virginia in 1863. At Gettysburg the caustic Jubal Early would “contend not only with an eccentric brigadier general but also the governor-elect of his state.” [44]

Avery

Colonel Isaac Avery commanded the 6th North Carolina and when Hoke was wounded at Chancellorsville took the brigade. Avery was described as having a “high moral worth,” “genial nature,” “stern inflexible fortitude,” and “chivalrous bearing.” [45] As a brigade commander he was an unknown quantity, and though “his peers had confidence in him, in Pennsylvania Avery would be going into battle for the first time at the head of a brigade of men who did not know him well.” [46]

Johnson’s Division

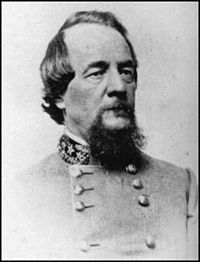

Major General Edward Johnson C.S.A.

Edward “Old Allegheny” Johnson, an old regular, a graduate of the West Point class of 1838. He had a solid record of service in the old Army. Johnson served in the Seminole War and received brevet promotions to Captain and Major during the Mexican War. Like many officers that remained in the army after Mexico he served on the frontier on the Great Plains. He resigned his commission when Virginia seceded from the Union and was appointed Colonel of the 12th Virginia Infantry and soon was promoted to Brigadier General in December 1861. He commanded a brigade sized force with the grand name of “the Army of the Northwest” which fell under the command of Stonewall Jackson.[47] He was wounded in the ankle at the Battle of McDowell on May 8th 1862, but the wound took nearly a year to heal, imperfectly at that. He was a favorite of Jackson who insisted that he be promoted to Major General and be given a division.

He took command of Jackson’s old division when Ewell was promoted to command Second Corps after Jackson’s death after Chancellorsville. Despite his wealth of experience in the pre-war army and service with Jackson in the Valley, Johnson was an outsider to the division. Like so many others he had never commanded a division “with no real experience above the brigade level.” Likewise he was “unfamiliar with the qualities and limitations of his four new brigadiers.” [48] Despite this he becomes quite popular with some of his men, and because he walks with limp, and uses a long staff to help him walk “his boys sometimes call him “Old Club.” [49] Gettysburg is his first test as a division commander, but not one that he is given a real opportunity to excel.

As a division commander “Johnson developed a reputation that when he threw his troops into battle, the struck with the punch of a sledgehammer, exactly the way Lee wanted his commanders to fight.” [50] Johnson “does well in nearly all his fights, hits hard and wins the confidence of his men.” [51] He was considered for command of First Corps when Longstreet was seriously wounded during the Wilderness Campaign. [52] One of his subordinates agreed, writing “without hesitation that he was the best Division commander I have ever met with, a thorough soldier and capable officer. I have little doubt that as a corps commander he would have proved himself far superior to others that I knew….” [53]

In Johnson’s division the command situation was more unsettled. Like Johnson, all of his brigade commanders were new to their commands. Johnson’s division had four brigades commanded by Brigadier Generals George “Maryland Steuart, John Marshall Jones and James Walker, as well as Colonel Jesse Williams.

“Maryland” Steuart

Brigadier General George “Maryland” Steuart, was a tough regular army cavalry officer. Steuart was one of the few officers from Maryland who left the army for the Confederacy. He graduated from West Point in 1848 along with John Buford. He entered the army too late to serve in Mexico, but served with the 2nd Dragoons and the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment on the Great Plains. He resigned his commission and entered Confederate service. Initially commissioned as a Captain of Cavalry, he became Colonel of the 1st (Confederate) Maryland Regiment at Bull Run. The Marylander was promoted to Brigadier general in March of 1862 and commanded “brigades of cavalry and infantry in the Shenandoah Valley” under Jackson. [54]

His performance as a cavalry commander was “lackluster” and “he was reassigned to an infantry brigade, which he commanded at Cross Keys,” [55] where he was wounded by a canister ball in his chest, a wound that took a year to heal.

Some wonder why Steuart was not more severely handled by Jackson, who was a harsh disciplinarian and who preferred courts-martial charges on others, including Dick Garnett for similar performance issues. Douglas Southall Freeman believed that “As a Maryland soldier of stranding, Steuart was expected to have a large influence, especially on recruiting. If he we arrested as a failure, Marylanders of Southern sympathy would be disillusioned and resentful. Considerations of policy outweighed personalities.” [56] This is likely the case, the Confederacy was counting on bringing sizable numbers of Marylanders into the fold as late as 1863.

Returning to active service Steuart took command of a troubled brigade, whose commander, Brigadier General Raleigh Colston, “had just been relieved of duty by Lee after a disappointing performance as head of a division at Chancellorsville.” [57] Steuart was a strict disciplinarian, who “Lee hoped would bring harmony to a bickering brigade of Marylanders, Virginians, and North Carolinians.” [58] Though Steuart was somewhat eccentric, he trained hi men well and over time his men came to respect him. Fifty years later, one of the surviving Maryland Confederate Veterans said “No one in the war gave more completely and conscientiously every faculty, every energy that was in him to the southern cause.” [59]

J.M. Jones

Brigadier General John Marshall Jones also was a former regular who was an underclassman in Ewell’s company and a classmate of John Reynolds and Richard Garnett. He graduated thirty-ninth of fifty-two cadets in the class of 1841, and served in the infantry. He had a “routine career” and served on the frontier and was an instructor at West Point during the Mexican War, a position that he heled for seven years. [60]

He resigned his commission in 1861 and served as a staff officer. He had a had a well-known problem with alcohol which had earned him the nickname “Rum” at West Point [61] likely kept him out of command for the first part of the war. Unlike most of the former Regulars Jones had never held a field command, and instead “served in staff assignments at the division level, lastly as a lieutenant colonel” [62] under Early.

Though Ewell thought much of his abilities as a staff officer, Jones was an alcoholic, but by early 1863 he appeared “to have gotten himself sufficiently under control to warrant the opportunity to lead men in battle.” [63] Lee was not confident of the appointment and wrote to Jefferson Davis “Should [Jones] fail his duty, he will instantly resign.” If this meant that Jones’s enemy was strong drink, the new brigadier met and overcame that adversary.” [64] Like Johnson he was new to command at this level, he would continue to serve well until his death in the Wilderness in 1864.

Walker

Brigadier General James Walker commanded the “Stonewall” Brigade. Walker replaced the former brigade commander, Elisha Paxton, who had been killed at Chancellorsville. As a cadet at V.M.I. Walker had a confrontation with his instructor, Stonewall Jackson, where he challenged his professor to a duel. [65] The duel did not take place and Walker “was expelled from the school.” [66] After his expulsion worked in railway construction, then studied law and set up a practice in Pulaski Virginia.

After John Brown’s raid Walker formed a militia company which became part of the 4th Virginia, which a part of Jackson’s command. The past did not haunt him and he and Jackson had an “amicable” relationship during the war and “Jackson did what he could to advance Walker.” [67] Walker became Lieutenant Colonel of the 13th Virginia and took command when A.P. Hill was promoted to Brigadier general. He continued to command the 13th Virginia in Ewell’s division, earning praise from Jubal Early who called him “a most gallant officer, who is always ready to perform a duty.” [68] The solid regimental commander then served as acting commander of different brigades during the Seven Days, Antietam, where he was wounded, and Fredericksburg. Walker had a solid record of success and was deserving of his promotion.

He had just been promoted to Brigadier General and was given the honor of command of the Stonewall Brigade, over the distinguished colonels of all five of its regiments. The appointment of an outsider like Walker was “a shock” [69] and brought an outcry from these officers who “in protest tendered their resignations.” Lee handled the incident with great care, and the “resignations were so declined so quietly and with so much tact that no trace of the incident appears in official records.” [70] Likewise Walker dealt with the situation well, in large part due to his personality:

“He was an extrovert who loved to fight, a two-fisted drinker and practical joker who enjoyed life too much to engage in petty bickering with his new subordinates. By the end of his first month, the Virginians affectionately called the tall and muscular fighter “Stonewall Jim.” [71]

He would lead the brigade until it was annihilated with the rest of the division at Spotsylvania, where he lost an arm. He briefly returned to service to lead a division at the end of the war. Following the war he returned to his law practice as well as politics, serving in the House of Delegates, as Lieutenant Governor, and as a Republican a two term member of Congress in the 1890s.

Williams

Colonel Jesse Williams had just taken acting command of the brigade of Brigadier General Francis Nichols who had been wounded at Chancellorsville. Williams had commanded the 2nd Louisiana Regiment prior to Gettysburg, and had little previous military experience. He remained in commanded due to the lack of a suitable brigadier, “it was an ominous admission that superior, developed material of high command had been exhausted temporarily.” [72] After less than stellar performances at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg Williams returned to his regiment when the brigade received a new commander. He was killed in battle at Spotsylvania Court House on May 12th 1864.

Rodes’ Division

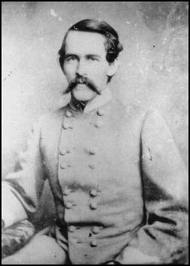

Major General Robert Rodes C.S.A.

Robert Rodes was a Virginia Military Institute graduate and professor who had never served in the Regular Army, the only non-West Point Graduate at the Corps or Division levels in the Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg. Thirty-two years old “more than six feet in height, with a drooping sandy mustache and a fiery, imperious manner on the field of battle” [73] Rodes “as the visage of a Viking warrior” [74] and looks like he had “stepped off the pages of Beowulf.” [75] His physical appearance “seemed a dramatic contrast to his one-legged eccentric corps commander and to the stoop and irascible Early.” [76] One of his Alabama soldiers who served under him when he commanded a brigade wrote “We fear him; but at the same time we respect and love him.” [77]

His career had been remarkable. Rodes was “tough, disciplined and courageous; he was one of those unusual soldiers who quickly grew into each new assignment.” [78] In just two years he had “risen from captaining a company of “Warrior Guards” in Alabama in 1861 to earning the equivalent of a battlefield promotion to major general for the fight he made at Chancellorsville.” [79] As a brigadier he had shown remarkable leadership on the battlefield and off, taking care of the needs of his soldiers and worked to have “at least one company per regiment to drill on a field gun and to keep up that training from time to time, so that his men could service a cannon in a crisis.” [80]

While Rodes only had briefly commanded a division before his appointment, he was a solid officer who in time became an excellent division commander, but at Gettysburg he was still new and untried. In the summer of 1863 Rodes “was one of the Army of Northern Virginia’s brightest stars…because of his effective, up-front style of combat leadership.” [81]

Rodes’ division was the largest in the army with five brigades present at Gettysburg. His brigade commanders were a mixed bag ranging from the excellent to the incompetent. Among the former he had George Doles, Stephen Ramseur and Junius Daniel. However, Rodes was saddled with two commanders of dubious quality, Brigadier General Alfred Iverson, who was hated by his men and Colonel Edward O’Neal, a leading secessionist politician “who had absolutely no military experience before the war” [82] and who had been ineffective as an acting brigade commander when he took over for Rodes at Chancellorsville, however, Lee was forced to leave at the head of his brigade for lack of other senior leaders over Rodes objections.

Doles

While Brigadier General George Doles of Georgia had no formal military training he was no stranger to military life. He ran away from home as a teenager to join the army in the Mexican War but was caught before he could join. He later served in the Georgia militia where he commanded a company, “the Baldwin Blues,” one of the oldest and best-trained military units in the state.” [83] As a Colonel he “had shown fiber and distinction” [84] as commander of the 4th Georgia. He was promoted to Brigadier General after Antietam, and commanded the brigade at Chancellorsville. By Gettysburg he had a reputation for “being among the Southern army’s most daring, hard fighting brigadiers.” [85]

Ramseur

Raided in a devout Presbyterian home in North Carolina, Brigadier General Stephen Ramseur attended Davidson College, a Presbyterian before being accepted into West Point. He graduated fourteenth of forty-one cadets in the West Point class of 1861, the last to graduate before the Civil War commenced. [86]

Ramseur was commissioned as an artillery officer, but resigned shortly after to join the new Confederate army in Alabama even before his native state of North Carolina had seceded. Within seven months he would be a Brigadier General. He was elected captain of the Ellis Light Artillery of Raleigh North Carolina, and became colonel of the 49th Alabama in 1862. He led that regiment at Malvern Hill where he was badly wounded. Ramseur was noted for “being a fighter and for his skill in handling troops in battle.” [87] Ramseur was promoted to Brigadier General in late 1862, becoming the youngest general in the army and led a North Carolina brigade with great daring at Chancellorsville where he was wounded in the shin by a shell fragment. Along with his division commander Robert Rodes, the still injured Ramseur was “one of the brightest lights in Lee’s army as it approached the field at Gettysburg.” [88]Jubal Early, who he succeeded as a division commander when Early took command of Second Corps in 1864 said that Ramseur “was a most gallant and energetic officer whom no disaster appalled, but his courage and energy seemed to gain new strength in the midst of confusion and disorder.” [89] The young General was mortally wounded at Cedar Creek on October 19th 1864 shortly after hearing about the birth of a child.

Daniel

Brigadier General Junius Daniel, a former regular and graduate of the West Point Class of 1851. He had resigned his commission as a lieutenant in 1858 to manage a family planation, but when war came volunteered for service where he served as commander of the 14th North Carolina. [90] He commanded a brigade on the Peninsula and was promoted to Brigadier General in September 1862.

Daniel had much brigade command time but little combat experience, as his brigade had been posted in North Carolina and the Virginia Tidewater and thus had not shared in the Army of Northern Virginia’s year of glory and slaughter. “Daniel’s brigade joined Rodes division in Virginia as a result of the army’s reorganization after Chancellorsville and in time for it to take part in the invasion of Pennsylvania.” [91] Despite the lack of combat experience Junius Daniel was well respected and “had the essential qualities of a true soldier and successful officer, brave, vigilant, honest…gifted as an organizer and disciplinarian, skilled in handling troops.” [92] At Gettysburg he “proved himself a valiant soldier and capable leader….” [93] This officer too would be killed in the fighting in the Wilderness.

O’Neal

Colonel Edward O’Neal was an Alabama Lawyer who occasionally dabbled in politics and after the war was elected Governor of Alabama. He won his rank due to his political connections as nothing he “had studied or experienced before 1861 had prepared him for military command at any level.” [94] In acting command at Chancellorsville he handled Rodes old brigade badly and bungled his assignment when Jackson “gave the go-ahead to commence his famous flank attack.” [95] O’Neal was “quarrelsome and unhappy under Rodes, still mired at the rank of colonel and convinced that Rodes was planning to replace him.” [96]

In fact Rodes had recommended other officers for the position, but was turned down by Lee. However, Lee did not have anyone suitable to take command of the brigade and left O’Neal in command, though he “blocked O’Neal’s promotion to brigadier general…Obviously if Lee distrusted O’Neal’s ability as a brigade commander, Rodes would have to give special attention to his old brigade in the fight ahead.” [97]

Iverson

Brigadier General Alfred Iverson had served in Mexico as a teen and gained a direct appointment to the Regular army “with the help of his congressman father” [98] and served as a Lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Cavalry until Georgia seceded. He was “a Richmond political pet whose promotion was deeply resented by his North Carolina brigade as a vote of no confidence in their political loyalties.” [99] His brigade had never been in combat and “the four regiments …needed judicious and competent leadership. Instead they had Alfred Iverson.” [100] Iverson was at constant loggerheads with his officers and once attempted to arrest all twenty six officers of his former regiment. [101]

The situation faced by Ewell, a new corps commander working with three new division commanders, each of whom had a mixture of subordinates that ranged from stellar to incompetent was unfortunate. Though he kept most of Stonewall Jackson’s experienced headquarters staff, he was new to them as a commander. Unlike Longstreet who’s First Corps maintained good continuity among its senior leadership and units, Ewell’s command was just beginning to coalesce as the campaign began.

Notes

[1] Ibid. Taylor, John Duty Faithfully Performed p.130

[2] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.322

[3] Pfanz, Donald. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier’s Life University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 1998 p.9

[4] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.11

[5] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.24

[6] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.33

[7] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.266

[8] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.99

[9] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.121

[10] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.172

[11] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.209

[12] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.220

[13] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.209

[14] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.322

[15] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.214

[16] Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg: A.P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell in a Difficult Debut in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.47

[17] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.47

[18] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.48

[19] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p..49

[20] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee an abridgment by Richard Harwell, Touchstone Books, New York 1997 p.305

[21] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.23

[22] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.279

[23] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.268

[24] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.268

[25] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.206

[26] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.155

[27] Osborne, Charles C. Jubal: The Life and Times of General Jubal A. Early, CSA Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill NC 1992

[28] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.83

[29] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.33

[30] Ibid. Osborne Jubal p.385

[31] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.207

[32] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p.397

[33] Ibid. Osborne Jubal p.50

[34] Gallagher, Gary W. Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy; Frank L Klement Lecture, Alternate Views of the Sectional Conflict Marquette University Press Marquette WI 2003 p.11

[35] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.256

[36] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.262

[37] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.41

[38] Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC 1993 p.206

[39] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.534

[40] Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC 1993 p.69

[41] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.380

[42] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.123

[43] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.53

[44] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.70

[45] Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC 1993 p.240

[46] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.268

[47] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.123

[48] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg pp.269-270

[49] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.47

[50] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.345

[51] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.47

[52] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.672

[53] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.227

[54] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.312

[55] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.312

[56] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.216

[57] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.273

[58] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.54

[59] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.313

[60] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.206

[61] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.276

[62] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.206

[63] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.276

[64] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.530

[65] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.156

[66] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.154

[67] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.530

[68] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p. 279

[69] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.156

[70] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.530

[71] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p. 278

[72] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.530

[73] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.39

[74] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg p.53

[75] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.39

[76] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p.147

[77] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.178

[78] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.243

[79] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg p.53

[80] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.244

[81] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p. 284

[82] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.299

[83] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.287

[84] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.386

[85] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.288

[86] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.289

[87] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001

[88] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.290

[89] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.251

[90] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.179

[91] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.179

[92] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.292

[93] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.21

[94] Krick, Robert K. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day of Gettysburg in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.120

[95] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.298

[96] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[97] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.162

[98] Ibid. Pfanz . Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.152

[99] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.170

[100] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.129

[101] Ibid. Krick Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.129