Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

This is another repost of my Gettysburg campaign series and one of the segments on the problems faced by Robert E. Lee as he attempted to find experienced and competent senior leaders to fill Corps, Division and Brigade command positions which were vacant due to the deaths of so many competent commanders over the past year of combat.

Of course, I am doing this in order to finish “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory” this weekend. If I wrote about anything else it would consume too much time. I have cut back on my social media as well as I make this final push.

I hope you enjoy. Please be safe.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

An issue faced by armies that are forced to expand to meet the demands of war is the promotion and selection of competent leaders at all levels of command. It has been an issue throughout American military history including during our recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The expansion of forces, the creation of new units and operational demands to employ those units sometimes result in officers being promoted, selected to command, being given field command or critical senior staff positions when in normal times they would not. To be fair, some do rise to the occasion and perform in an exemplary manner. Others do not. Those leaders that do not are quite often weeded out over the course of time but often not before their lack of experience, or incompetence proves disastrous on the battlefield. As Barbara Tuchman so eloquently put it:

“When the moment of live ammunition approaches, the moment to which all his professional training has been directed, when the lives of the men under him, the issue of the combat, even the fate of a campaign may depend upon his decision at a given moment, what happens inside the heart and vitals of a commander? Some are made bold by the moment, some irresolute, some carefully judicious, some paralyzed and powerless to act.” [1]

Stonewall Jackson was dead and with his death after the Pyrrhic victory at Chancellorsville General Robert E. Lee was faced with the necessity of reorganizing his army. Jackson’s loss was disastrous for Lee, for he lost the one man who understood him and his method of command more than anyone, someone for whom he had a deep and abiding affection. Months before Jackson’s death Lee said of him “Such an executive officer the sun has never shown on, I have but to show him my design, and I know that it if it can be done it will be done.” [2] After Jackson’s loss Lee said “I had such implicit confidence in Jackson’s skill and energy that I never troubled myself to give him detailed instructions. The most general suggestions were all that he needed.” [3] Lee met the loss with “resignation and deep perplexity,” his words displayed that sense of loss, as well as his sense of faith and trust in God’s providence “I know not how to replace him. God’s will be done. I trust He will raise someone up in his place…” [4]

In addition to the loss of Jackson, a major part of Lee’s problem was organizational. In 1862 Lee inherited an army that was a “hodgepodge of forces” [5]which was organized in an “unwieldy divisional command system, where green commanders out of necessity were given considerable independence.” [6] That organization was tested and found wanting during the Seven Days campaign where on numerous occasions division commanders failed to coordinate their actions with those of adjacent divisions or failed to effectively control their own troops during movement to contact or combat.

Shortly after the Seven Days Lee reorganized the army, working with the material that he had. He divided the army into two corps, under Jackson and James Longstreet, each composed of four divisions consisting of about 30,000 troops apiece. While both commanders were technically equals, it was Jackson to whom Lee relied on for the most daring tasks, and whom he truly considered his closest confidant and his “executive officer.”

The organization worked well at Second Manassas, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, although Longstreet’s corps was detached from the army at the time of the latter, and with the loss of Jackson on the first night of that battle neither A.P. Hill nor J.E.B. Stuart effectively commanded Second Corps during the remainder of the battle.

Longstreet and Jackson served to balance each other and each enjoyed the trust of Lee. Lee’s biographer Michael Korda calls them the:

“yin and yang of subordinates. Jackson was superb at guessing from a few words exactly what Lee wanted done, and setting out to do it immediately without argument or further instructions; Longstreet was as good a soldier, but he was an instinctive contrarian and stubbornly insisted on making Lee think twice, and to separate what was possible from what was not.” [7]

Both men had been instrumental to Lee’s battlefield success and both played indispensable roles in Lee’s ability to command the army.

Likewise, the sheer size of Lee’s formations posed problems both in moment and combat, as Lee noted “Some of our divisions exceed the army Genl Scott entered Mexico with, & our brigades are larger than divisions”…that created stupendous headaches in “causing orders & req[uisitions] to be obeyed.” [8] Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis on May 20th “I have for the past year felt that the corps of the army were too large for one commander. Nothing prevented my proposing to you to reduce their size and increase their number but my inability to recommend commanders.” [9]

In the hands of Longstreet and Jackson these massive corps were in the good hands of leaders who could effectively handle them, “but in anyone else’s hands, a corps the size of Jackson’s or Longstreet’s might prove so big as to become clumsy, or even worse, might call for a degree of micromanagement that Lee and his diminutive staff might not be able to deliver.” [10] Thus Lee did not try to replace Jackson; he wrote to Davis the reasons for creating a new corps:

“Each corps contains in fighting condition about 30,000 men. These are more than one man can handle & keep under his eye in battle….They are always beyond the range and vision & frequently beyond his reach. The loss of Jackson from the command of one half of the army seems to me a good opportunity to remedy this evil.” [11]

Instead of appointing one man to command Second Corps, Lee reorganized the army and created two corps from it, stripping a division of Longstreet to join the new Third Corps and dividing the large “Light” Division of A.P. Hill, which under Hill’s “intelligent administration probably is the best in the army” [12] into two divisions.

The problem for Lee was just who to place in command of the new corps and divisions that he was creating. Lee was deeply aware of this problem, and wrote to John Bell Hood that the army would be “invincible if it could be properly organized and officered. There never were such men in an Army before. The will go anywhere and do anything if properly led. But there is the difficulty-proper commanders- where can they be obtained?” [13] Lee sought the best commanders possible for his army, but the lack of depth in the ranks of season, experienced commanders, as well as the need to placate political leaders made some choices necessary evils.

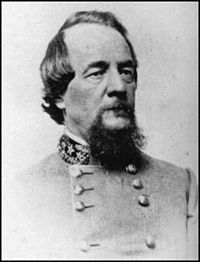

The First Corps, under Longstreet remained relatively intact, but was now less the division of Major General Richard Anderson, which was transferred to the new Third Corps. The First Corps now had three divisions instead of four, those of Major General Lafayette McLaws, Major General John Bell Hood and Major General George Pickett. McLaws and Hood were both experienced division commanders who worked well under Longstreet.

McLaws had served in the old army. An 1842 graduate of West Point McLaws served in the infantry and was resigned from the army in 1861 to take command of a Georgia regiment. McLaws was “a capable soldier without flair, who steady performance never produced a high moment. His reliability and dogged tenacity rubbed off on his men, however, and made them as hard to dislodge as any in the army.” [14] Porter Alexander noted that in the defense “McLaws was about the best in the army…being very painstaking about details, & having an eye for good ground.” [15] But there was a drawback, for all of his solidness and fortitude “he lacked a military imagination,” and was “best when told exactly what to do and closely supervised by superiors.” [16]His division was typical of many in First Corps, “outstanding on defense and led by a competent soldier, they were thoroughly dependable. With the reliance of old pro’s, they did what they were told, stood up under heavy casualties, and produced tremendous firepower.” [17]

McLaws was fortunate to have solid brigade commanders, three of whom had served with him from the beginning, so the lack of familiarity so common in the divisions of Second and Third Corps was not an issue. Interestingly none were professional soldiers.

Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw was a lawyer and politician he had served in Mexico with the Palmetto Regiment and volunteered for service as South Carolina succeeded and he was at Fort Sumter. As commander of the 2nd South Carolina and as a brigade commander he distinguished himself during the Seven Days, Antietam and Fredericksburg He displayed an almost natural ability for “quick and rational decisions, and he never endangered his men rashly. McLaws had complete faith in him and his brigade…” [18]

Brigadier General Paul Semmes was a banker and plantation owner from Georgia and the brother of the Confederacy’s most famous naval commander, Raphael Semmes, who commanded the Raider C.S.S. Alabama. Semmes “was well known in Georgia as a man both of military tastes & accomplishments before the war & though of no military education he was one of the first generals created.” [19] He commanded the 2nd Georgia Regiment and by 1862 was in command of McLaws’ old brigade which he led with distinction during the Seven Days, Antietam and Chancellorsville. By Gettysburg he “had proved himself a worthy and capable brigadier” [20] and Porter Alexander wrote “and it is due to say that there was never a braver or a better.” [21]

Brigadier General William Barksdale was a Mississippi lawyer, newspaper editor and politician who had served in Mexico as a quartermaster, but who “frequently appeared at the front during heavy fighting, often coatless and carrying a large sword.” [22] He was one of the few generals who had been “violently pro-slavery and secessionist” [23] and as a Congressman had been involved in the altercation where Representative Preston Brooks nearly killed Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate chamber. At the outbreak of the war Barksdale volunteered for service and took command of a brigade at Malvern Hill and at Antietam and Fredericksburg was in the thick of the fight. He had a strong bond with his soldiers.

Brigadier General William Wofford was the newest of McLaws’ brigade commanders. Wofford was a Georgia newspaper owner and lawyer who had done a great deal of fighting in the Mexican War where he commanded a company despite having no military education. He was considered a man of “high morale bearing…of the strictest sobriety, and, indeed of irreproachable moral character.” [24] Demonstrating the tensions of the day Wofford was a “staunch Unionist Democrat” who “opposed secession and voted against it at the Georgia secession convention.” [25] Wofford volunteered for service and was “elected colonel of the first Georgia regiment to volunteer for the war.” [26] That being said Wofford “was a decided Union man from first to last during the whole war” and saw “with exceptional prescience…the certain fatality” of secession, but once the deed was done, he closed ranks…” [27] Wofford served well as a regimental commander and acting brigade commander during the Seven Days, Second Manassas, Antietam and Fredericksburg and was promoted to the brigadier general and command of a brigade just before Chancellorsville.

Major General John Bell Hood was an 1853 graduate of West Point and had served as a cavalry officer under Lee’s command in Texas. He gained a stellar reputation as a leader and fighter and when his home state of Kentucky did not secede he attached himself to his adopted state of Texas. He began the war as a lieutenant but by 1862 was a Brigadier General commanding the only Texas brigade in the east. He took command of a division following the Seven Days and during the next year built a “combat record unequalled by any in the army at his level.” [28] And the “reputation gained as commander of the Texas Brigade and as a division commander made him both a valuable general officer and a celebrity who transcended his peers.” [29]

Hood’s brigade commanders were as solid as group as any in the army:

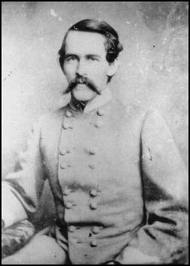

Brigadier General Evander Law was a graduate of the South Carolina Military (the Citadel) and a professor in various military colleges and schools before the war. He served admirably as a regiment and brigade commander during the Seven Days, Second Manassas, and Antietam and was promoted to brigadier general in October 1862 just prior to Fredericksburg. After Chancellorsville he was the senior brigadier in Hood’s division. He had “military training, youth, dash ability and familiarity with his men- a formidable package in combat.” [30]

Brigadier General George “Tige” Anderson was a Georgian who had served in Mexico as a lieutenant of Georgia cavalry and in 1865 was commissioned as a captain in the Regular cavalry, but resigned after three years. He had no formal military training but was considered a capable officer. He was present at most of the major battles fought by the Army of Northern Virginia but in most cases his brigade had not been heavily engaged and had “little chance to distinguish himself” but he was loved by his soldiers. One wrote that he “stands up for us like a father” while another wrote “He is always at his post.” [31]

Hood’s old Texas Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General Jerome Robertson. At the age of forty-eight he had served with Sam Houston in the Texas War for Independence and later took time off to serve fighting Indians. He practiced medicine in Texas and in 1861 was a pro-secession delegate to the Texas secession convention. He was commissioned as a Captain and promoted to Colonel of the 5th Texas just prior to the Seven Days and led that unit to fame. He was promoted after Antietam to command the Texas Brigade. Away from most of the action at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville he would have his first combat experience as a brigade commander at Gettysburg.

Brigadier General Henry Benning was a lawyer and Georgia Supreme Court justice. While not having any military training or experience he was “known to all as a man of the highest integrity, and he was compared in character to that earlier champion of the South, John Calhoun. He was one of the most industrious and capable men in the Confederacy.” [32] Unlike other Confederate political leaders he favored a strong central government for the new South. He was considered a prime candidate for a cabinet post but had already decided to serve in the new army and helped organize the 17th Georgia Infantry. As a regiment commander and acting brigade commander at Antietam, his brigade had held off Burnside’s corps at the Burnside Bridge and became known as “Old Rock” [33]and was a “proven commander” who “provided strong leadership and bolstered the confidence of the men under him.” [34]

Major General George Pickett had commanded his division for some time, but Pickett “had never led his division in combat.” [35] Likewise the brigades of his division had not fought together in a major engagement and the division was new to fighting as a part of First Corps. The campaign would also be Pickett’s first offensive campaign as a division commander. Pickett was an 1846 graduate of West Point who though well liked “showed evidence of a meager intellect and aversion to hard work.” [36] However he distinguished himself by his gallantry at Chapultapec in the Mexican War where taking the colors from the wounded Longstreet and “carried them over the wall” [37] gaining fame around the country for the exploit. Pickett was a protégé of Longstreet who “had been instrumental in Pickett’s appointment to divisional command.” [38] Pickett was was “untried at his new rank, but had been an excellent brigade leader and with Longstreet’s full support was apt to direct with wisdom his larger force.” [39]

Pickett’s division only had three of his five brigades at Gettysburg. Two were commanded by old Regular officer’s Richard Garnett and Lewis Armistead, and the third by James Kemper.

Brigadier General James Kemper was the only non-professional soldier of the three brigade commanders. Kemper had been a captain of volunteers in the Mexican War, but that war ended before he could see action. He was a politician who had served twice as Virginia’s Speaker of the House and “was another of those civilian leaders who, accustomed to authority, translated their gifts to command in the field.” [40] During his time as a legislator Kemper had served as “chairman of the Military Affairs Committee in the years before the Civil War, and insisted on a high level of military preparedness.” [41] Kemper served as commander of the 7th Virginia Regiment and was promoted to brigadier general after Seven Pines and commanded the brigade at Second Manassas and Antietam. He was “very determined and was respected by brother officers for solid qualities and sound judgment.” [42]

Brigadier Richard Garnett came to his command and to Gettysburg under a cloud. He was a West Point graduate, class of 1841who strong Unionist, but who had resigned his commission in the Regular Army because he “felt it an imperative duty to sacrifice everything in support of his native state in her time of trial.” [43]Garnett had run afoul of Jackson while commanding the Stonewall Brigade and during the Valley campaign had been relieved of command and arrested by Jackson for ordering a retreat without Jackson’s permission. Garnett had been “humiliated by accusations of cowardice” [44] and demanded a court-martial which never was held as Lee transferred him away from Jackson to Pickett’s division. Gettysburg offered him “his first real opportunity with Pickett’s division to clear his honor as a gentleman and a soldier.” [45]

Pickett’s last brigade was commanded by an old Regular, and longtime friend and comrade of Garnett, Brigadier General Lewis Armistead. He was expelled from West Point following a dinning room brawl with Jubal Early, in which he smashed a plate on Early’s head. However, later was commissioned directly into the infantry in 1839. He fought in the Mexican War where he received two brevet promotions for gallantry and was wounded at Chapultapec. Like Garnett Armistead resigned his commission in 1861 to serve in the Confederate army where he took command of the 57th Virginia Infantry and shortly thereafter was promoted to Brigadier General. He held brigade command and served Provost Marshal during Lee’s 1862 invasion of Maryland. He had seen little action since Second Manassas, but was known for “his toughness, sound judgment and great personal courage.” [46]

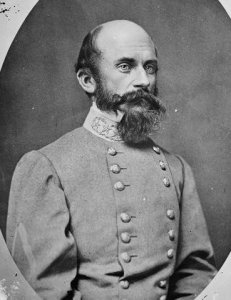

To command what was left of Second Corps Lee promoted Major General Richard Ewell to Lieutenant General. Ewell had been an effective and dependable division commander under Jackson but had been wounded at Groveton where he was severely wounded and lost a leg, which meant the “absence for long months of the most generous, best disciplined, and in many soldierly qualities, the ablest of Jackson’s subordinates.” [47] However, Ewell, though serving long with Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley had served “only briefly under Lee” [48] before being wounded at Groveton. The result was that neither fully knew or understood each other. Lee knew Ewell’s excellent reputation among the soldiers of Second Corps and “may have heard rumors that on his deathbed Jackson expressed a preference for Ewell as his successor.” [49] Ewell was a modest man and “had maintained a reputation for solid competence.” [50] Freeman wrote:

“In part, the appointment of Dick Ewell was made because of sentimental association with the name Jackson, and in part because of admiration for his unique, picturesque, and wholly lovable personality. Of his ability to lead a corps nothing was known. Ewell had never handled more than a division and he had served with Lee directly for less than a month.” [51]

In sending the recommendation on to Richmond Lee termed Ewell “an honest, brave soldier, who has always done his duty well.” [52] It was not a resounding recommendation, but then Lee barely knew Ewell. Lee wrote after the war that he recommended Ewell “with full knowledge of “his faults as a military leader- his quick alternations from elation to despondency[,] his want of decision &c.” [53]Many questions hovered around the appointment of Ewell including how the loss of his leg, his recent marriage, newness to corps command and unfamiliarity with Lee’s style of command would have on him. Had Lee known that the humble Ewell had reservations of his own about assuming command of a corps and going back to battle after the traumatic amputation of his leg, he had written “I don’t feel up to a separate command” and he had “no desire to see the carnage and shocking sights of another field of battle.” [54]

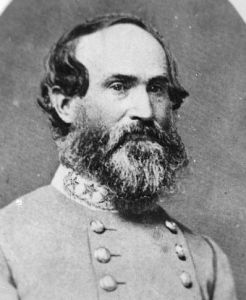

Ewell’s reorganized Second Corps now consisted of his former division, commanded since Antietam by Major General Jubal Early. Early was an unusual character. He was a West Point graduate who had served in the Seminole wars, left the army and became a highly successful lawyer. He served in the Mexican war as a Major with Virginia volunteers and returned to civilian life. He was “notoriously a bachelor and at heart a lonely man.” Unlike many Confederate officers he had “no powerful family connections, and by a somewhat bitter tongue and rasping wit” isolated himself from his peers.[55] He was a Whig and opposed succession, volunteering for service only after Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to crush the rebellion. Called the “my old bad man” by Lee, who “appreciated Early’s talents as a soldier and displayed personal fondness for his cantankerous and profane Lieutenant …who only Stonewall Jackson received more difficult assignments from Lee.” [56] He was affectionately known as “Old Jube” or “Jubilee” by his soldiers he is the most influential of Ewell’s commanders, and his “record in battle prior to Gettysburg was unsurpassed.” [57]

The corps had tow other divisions, one, the former division of Stonewall Jackson under the command of Edward “Old Allegheny” Johnson, an old regular with a solid record of service. However, Johnson had spent a year recovering from a serious wound and took command of the division after Chancellorsville. He was an outsider to the division, “with no real experience above the brigade level” and he was “unfamiliar with the qualities and limitations of his four new brigadiers.” [58] The former division of D.H. Hill was now under the command of Robert Rodes, a VMI graduate and professor who had never served in the Regular Army and only had briefly commanded a division before his appointment to command. Rodes was a solid officer who in time became an excellent division commander, but at Gettysburg he was still new and untried. In the summer of 1863 Rodes was one of the Army of Northern Virginia’s brightest stars…because of his effective, up-front style of combat leadership.” [59]

The brigade level commanders in the corps were another matter. Early’s division included standouts such as Brigadier General John Gordon and Harry Hays, which was balanced out by the weakness of Brigadier General William “Extra Billy” Smith and the inexperience of Colonel Isaac Avery, who commanded the brigade of Robert Hoke who had been wounded at Chancellorsville.

In Johnson’s division the situation was even more unsettled, as Johnson and all of his brigade commanders were new to their commands. Johnson had the brigades of Brigadier General George “Maryland” Steuart, a tough old regular cavalry officer who was new to command of a troubled brigade whose commander had just been relieved. Brigadier General John Marshall Jones who also was a former regular commanded his second brigade, but Jones had a well-known problem with alcohol and had never held a field command. He like his division commander he was new to the division. Brigadier General James Walker commanded the “Stonewall” Brigade. Walker replaced the former brigade commander, Paxton who had been killed at Chancellorsville. He had commanded the 13th Virginia in Ewell’s division and served as acting commander of different brigades during the Seven Days, Antietam and Fredericksburg and had a solid record of success. He had just been promoted to Brigadier General and was new to both the Stonewall Brigade and the division. Many Stonewall Brigade officers initially resisted the appointment of an outsider but soon warmed up to their new commander. The commander of his fourth brigade, Colonel Jesse Williams had just taken command of that brigade fro. Brigadier General Francis Nichols who had been wounded at Chancellorsville.

Rodes’s division was the largest in the army. It had five brigades present at Gettysburg. Rodes’s brigade commanders were a mixed bag ranging from the excellent Brigadier General George Doles, the young Brigadier General Stephen Ramseur, and Brigadier General Junius Daniel, a former regular who had much brigade command time but little combat experience. Despite his lack of combat experience Daniel was well respected and “had the essential qualities of a true soldier and successful officer, brave, vigilant, honest…gifted as an organizer and disciplinarian, skilled in handling troops.” [60]However, Rodes was saddled with two commanders of dubious quality, Brigadier General Alfred Iverson, who was hated by his men and Colonel Edward O’Neal, a leading secessionist politician “who had absolutely no military experience before the war” [61] and who had been ineffective as an acting brigade commander when he took over for Rodes at Chancellorsville, however, Lee was forced to leave O’Neal at the head of his brigade for lack of other senior leaders over Rodes objections.

To be continued…

Notes

[1] Tuchman, Barbara The Guns of August Ballantine Books, New York 1962 Amazon Kindle edition location 2946

[2] Taylor, John M. Duty Faithfully Performed: Robert E Lee and His Critics Brassey’s, Dulles VA 1999 p.128

[3] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.30

[4] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.524

[5] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.30

[6] Hagerman, Edward. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare.Midland Book Editions, Indiana University Press. Bloomington IN. 1992 p.110

[7] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.527

[8] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 pp.20-21

[9] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993

[10] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.20-21

[11] Thomas, Emory Robert E. Lee W.W. Norton and Company, New York and London 1995 p.289

[12] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.35

[13] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.12

[14] Tagg, Larry The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle Da Capo Press Cambridge MA 1998 Amazon Kindle Edition pp.208-209

[15] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p.170

[16] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.209

[17] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.176

[18] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.214

[19] Ibid. Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy p.80

[20] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.217

[21] Ibid. Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy p.80

[22] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg pp.217-218

[23] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.217

[24] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.296

[25] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.221

[26] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.297

[27] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.296-297

[28] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.224

[29] Pfanz, Harry F. Gettysburg: The Second Day. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1987 p.161

[30] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.228

[31] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.230

[32] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.234

[33] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.430

[34] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.235

[35] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.12

[36] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.237

[37] Ibid. Wert General James Longstreet p.45

[38] Wert, Jeffery D. Gettysburg Day Three A Touchstone Book, New York 2001 p.110

[39] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.385

[40] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.268

[41] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.241

[42] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.269

[43] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.269

[44] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.379

[45] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.270

[46] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.244

[47] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.322

[48] Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg: A.P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell in a Difficult Debut in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.47

[49] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.47

[50] Ibid. Taylor, John Duty Faithfully Performed p.130

[51] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.322

[52] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.48

[53] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p..49

[54] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.23

[55] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.33

[56] Gallagher, Gary W. Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy; Frank L Klement Lecture, Alternate Views of the Sectional Conflict Marquette University Press Marquette WI 2003 p.11

[57] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.256

[58] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg pp.269-270

[59] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p. 284

[60] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.292

[61] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.299