Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

Since I am now working my way back to Gettysburg his is a significant revision of an article that I published here earlier in the year and that is a part of my Gettysburg Staff Ride text. The actual full title of the chapter is The Foundations of the First Modern War: The Character, Nature and Context of the Civil War and its Importance to Us Today but that is rather long to put as the title here. This is pretty detailed and specialized so many may not want to read it, however, for those with in interest in how United States policy in regard to how we use our military today and the myriad of tensions that we wrestle with that have been with us for about 150 years it should prove enlightening.

Since it is pretty long I am dividing it up between two posts. Have a great day!

Peace

Padre Steve+

The First Modern War

The American Civil War was the first modern war. It was a watershed time which introduced changes in tactics, logistics, and communications, while showed the world exactly what the concept of total war entailed. Though it did not change the essential nature of war, which Clausewitz says is “is an act of violence to compel our opponent to fulfil our will” [1] it expanded the parameters of it and re-introduced the concept of “total war” to the world and “because its aim was all embracing, the war was to be absolute in character.”[2] In a sense it was a true revolution in military affairs.

Thus it is important to study the Gettysburg campaign in the context of the Civil War, as well as in relationship to the broader understanding of the nature and character of war. To do this one must examine the connection between them and policies made by political leaders; to include the relationship of political to military leaders, diplomats, the leaders of business and industry and not to be forgotten the press and the people. Likewise we must understand the various contexts of war, how they impacted Civil War leaders and why they must be understood by civilian policy makers and military leaders today.

While the essential nature of war remains constant, wars and the manner in which they are fought have changed in their character throughout history, and this distinction matters not only for military professionals, but also policy makers. The changing character of war was something that military leaders as well as policy makers struggled with during the American Civil War much as today’s military leaders and policy makers seek to understand the character of warfare today. British military theorist Colin Gray writes “Since the character of every war is unique in the details of its contexts (political, social-cultural, economic, technological, military strategic, geographical, and historical), the policymaker most probably will struggle of the warfare that is unleashed.” [3] That was not just an issue for Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, both of whom struggled with the nature of the war which had been unleashed, but it is one for our present political leaders, who as civilian politicians are “likely to be challenged by a deficient grasp of both the nature of war as well as its contemporary context-specific character.” [4]

In addition to being the first modern war, or maybe I should say, the first war of the Industrial Age, the Civil War became a “total war.” It was the product of both the massive number of technological advances which both preceded and occurred during it, in which the philosophical nature of the Industrial Revolution came to the fore. Likewise, the enmity of the two sides for one another which had been fostered by a half century of relentless and violent propaganda which ushered from the mouths of politicians, the press and even from the pulpit, even to the point of outright armed conflict and murder in “Bleeding Kansas” during the 1850s.

As a total war it became a war that was as close to Clausewitz’s understanding of absolute war in its in character waged on the American continent, and it prefigured the great ideological wars of the twentieth century, as J.F.C. Fuller noted “for the first time in modern history the aim of war became not only the destruction of the enemy’s armed forces, but also of their foundations- his entire political, social and economic order.” [5] It was the first war where at least some of the commanders, especially Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman were men of the Industrial Age, in their thought and in the way that they waged war, in strategy, tactics even more importantly, psychologically. Fuller wrote:

“Spiritually and morally they belonged to the age of the Industrial Revolution. Their guiding principle was that of the machine which was fashioning them, namely, efficiency. And as efficiency is governed by a single end- that every means is justified- no moral or spiritual conceptions of traditional behavior must stand in its way.” [6]

Both men realized in early 1864 that “the South was indeed a nation in arms and that the common European practice of having standing armies engaged each other in set-piece battles to determine the outcome of a war was not enough to win this struggle.” [7] Though neither man was a student of Clausewitz, their method of waging war was in agreement with the Prussian who wrote that “the fighting forces must be destroyed; that is, they must be put in such a position that they can no longer carry on the fight” but also that “the animosity and the reciprocal effects of hostile elements, cannot be considered to have ended so long as the enemy’s will has not been broken.” [8] Sherman told the mayor of Atlanta after ordering the civilian population expelled that “we are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make the old and young, the rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war.” [9] Sherman not only “carried on war against the enemy’s resources more extensively and systematically than anyone else had done, but he developed also a deliberate strategy of terror directed against the enemy’s minds.” [10]

Abraham Lincoln came to embrace eternal nature of war as well as the change in the character of the war over time. Lincoln had gone to war for the preservation of the Union, something that for him was almost spiritual in nature, as is evidenced by the language he used in both of his inaugural addresses and the Gettysburg Address. Instead of a war to re-unite the Union with the Emancipation Proclamation the war became a war for the liberation of enslaved African Americans, After January 1st 1863 when the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, Lincoln “told an official of the Interior Department, “the character of the war will be changed. It will be one of subjugation…The [old] South is to be destroyed and replaced by new propositions and ideas.” [11]

Of course, the revolution in military affairs took time and it was the political and military leaders of the North who better adapted themselves and their nation to the kind of war that was being fought. “Lincoln’s remarkable abilities gave him a wide edge over Davis as a war leader, while in Grant and Sherman the North acquired commanders with a concept of total war and the determination to make it succeed.” [12]

At the beginning of the war the leaders and populace of both sides still held a romantic idea of war. The belief that the war would be over in a few months and that would be settled by a few decisive battles was held by most, including many military officers on both sides, there were some naysayers like the venerable General Winfield Scott, but they were mocked by both politicians and the press.

The Civil War became an archetype of the wars of the twentieth century, and the twenty-first century. It became a war where a clash between peoples and ideologies which extended beyond the province of purely military action as “it was preceded by years of violent propaganda, which long before the war had obliterated all sense of moderation, and awakened in the contending parties the primitive spirit of tribal fanaticism.” [13]

The conduct of the American Civil War added new dimensions to war, increased its lethality and for the first time since the 30 Years’ War saw opponents intentionally target the property, homes and businesses of civilian populations as part of their military campaign. The Civil War was a precursor to the wars that followed, especially the First World War which it prefigured in so many ways. [14]

However, like all wars many of its lessons were forgotten by military professionals in the United States as well as in Europe. Thus 50 years later during World War One, British, French, German, Austrian and Russian wasted vast amounts of manpower and destroyed the flower of a generation because they did not heed the lessons of the Civil War. Fuller noted:

“Had the nations of Europe studied the lessons of the Civil War and taken them to heart they could not in 1914-1918 have perpetuated the enormous tactical blunders of which that war bears record.” [15]

The lessons of the war are still relevant today. Despite vast advances in weaponry, technology and the distances with which force can be applied by opponents, war remains an act of violence to compel an enemy to fulfill our will. War according to Clausewitz is “more than a chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case.” [16] but it is always characterized by the violence of its elements, the province of chance and its subordination to the political objective and as such forces political and military leaders as well as policy makers to wrestle with “the practical challenge of somehow mastering the challenge of strategy in an actual historical context.” [17]

Colin Gray makes a case for seven essential contexts that must be understood by policy makers and military leaders regarding war, which if ignored or misunderstood “can have strong negative consequences.” [18] The contexts which Gray enunciates: a political context, a social-cultural context, an economic context; a military-strategic context, a geographic context and a historical context and as Gray notes they “define all the essential characteristics of a particular armed conflict.” [19]

The study of the Civil War can be helpful to the joint planner and commander because it so wonderfully shows the interplay of Clausewitz’s “paradoxical trinity- composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which are to be regarded as a blind natural force; of the play of chance and the element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to reason alone.” [20] during an era of great technological and philosophical change. The importance of this cannot be underestimated, for in this era of change, like in every era, some leaders and commanders were either resistant to, or failed to understand the changes being forced upon them in their conduct of war by the industrialization of war and its attendant technology; while others, like Sherman, Grant and Sheridan not only understood them, but embraced them and applied them with skill and vigor in ways that stunned the people of the South.

The Whole of Government and National Power

Over time the Union developed what we would now refer to as a “whole of government approach” to the war. This included not only the military instrument but the use of every imaginable means of national power, from the diplomatic, the economic and the informational aspects of the Union in the effort to subdue the Confederacy. The understanding and use of the “whole of government approach” to war and conflict is still a cornerstone of United States military policy in “unified action, to achieve leverage across different domains that will ensure conditions favorable to the U.S. and its allies will endure.” [21] The working staff of the War Department headed by Edwin Stanton and Major General Montgomery Meigs developed rapidly. It effectively coordinated with railroads, weapons manufactures and suppliers of clothing, food and other necessities to supply the army and navy so well that “Union forces never seriously lacked the materials necessary to win the war.” [22] Stanton and Meigs were “aided by the entrepreneurial talent of northern businessmen” which allowed “the Union developed a superior managerial talent to mobilize and organize the North’s greater resources for victory in the modern industrialized conflict that the Civil War became.” [23]

The understanding of this eternal nature and ever changing character of war to leaders of nations as well as military commanders and planners has been very important throughout history. It can be seen in the ways that Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln conducted their relationships with their military commanders, including during the Gettysburg campaign and we are reminded by Colin Gray notes that political leaders and policy makers who are in charge of policy often ignorant of the nature and character of war, and this fact “directs attention to the difficulties of translating political judgment into effective warmaking.” [24] Military leaders should be the people to advise and instruct policy makers in aligning their policy to what is actually feasible based on the ends ways and means, as well as the strengths and limitations of the military to carry out policy decisions and history reminds us “that policymakers committed strongly to their political desires are not easily deflected by military advice of a kind that they do not want to hear.” [25]

While there was much support for the Confederacy in the aristocracies of Europe, the effectiveness of the Union military in winning the key battles that allowed Lincoln to make his Emancipation Proclamation ensured that Europe would not recognize the Confederacy, . Charles F. Adams, the United States minister to Britain successfully defused the crisis of the Trent affair, which could have led to British recognition of the Confederacy and intervention in the war. Adams’ efforts were so successful that they “left Anglo-American relations in better shape than before the crisis.” [26]

The Trent Affair

The Importance of Diplomacy

Related to this understanding of warfare one has to also look at the importance of diplomacy, especially in picking the right diplomat for a critical post is a part of a whole of government approach to war and warfare. This was very important in the early stages of the Civil War as there was much support for the Confederacy in the aristocracies of Europe. The effectiveness of the diplomacy was increased by the Union military efforts. The Union suffered many failures at the outset of the war by the time of the Gettysburg campaign they did enough to prevent English or French intervention on the side of the Confederacy, which was also aided by tensions in Europe regarding the Schleswig-Holstein problem between Prussia and Austria as well as unrest in Poland, and the British in particular were loath to risk intervening in a conflict that might be “a disturbance in the precarious balance of power which might be the signal for a general conflagration, they recalled Voltaire’s comment that a torch lighted in 1756 in the forests of the new world had promptly wrapped the old world in flames.” [27] Thus, European leaders and diplomats were very hesitant to allow Southern legations to convince them to intervene.

Though the Confederates won many early battles in 1861 and 1862 it was the success of the Union military that altered the diplomatic landscape and helped doom the Confederacy. The joint operations conducted by Ulysses Grant and Flag Officer Foote at Island Number Ten, Fort Henry, Fort Donaldson and Shiloh opened the door to the western Confederacy making it vulnerable to Union invasion. Likewise, the joint operations conducted by the Union Navy and Army against the Confederacy through the blockade and capture of key ports such as New Orleans by 1862; combined with the bloody repulses of Confederate armies at Perryville and Antietam allowed Lincoln to make his Emancipation Proclamation, an act which reverberated across the Atlantic.

These military successes enabled Lord Palmerston to reject a French proposal for France, England and Russia to propose to the warring parties, a “North-South armistice, accompanied by a six month lifting of the blockade. The result, if they had agreed- as they had been in no uncertain terms warned by Seward in private conversations with British representatives overseas- would have been a complete diplomatic rupture, if not an outright declaration of war.” [28]

The issuance of that proclamation ensured that Europe would not recognize the Confederacy because even pro-Southern English political leaders could not appear to even give the appearance of supporting slavery, especially as both England and France had abolished slavery decades before, while Russia had only recently emancipated its serfs and “was pro-Union from the start….” [29] Popular sentiment in those countries, outside of the ruling class and business elites, was heavily in favor of emancipation, especially among the working classes. The leaders of the workingmen of Manchester England, a major textile producer, who which had been among the “hardest hit by the cotton famine, sent him [Lincoln] an address approved at a meeting on New Year’s Eve, announcing their support of the North in its efforts to “strike off the fetters of the slave.” [30]

There were issues related to the blockade but Charles F. Adams, the United States minister to Britain successfully defused the crisis of the Trent affair, which could have led to British recognition of the Confederacy and intervention in the war in a manner that “left Anglo-American relations in better shape than before the crisis.” [31]

The Union blockade was a key factor in the diplomatic efforts. As I have noted there were many in both Britain and France who sympathized with the South and hoped for Southern victory that were not impressed by Southern moves to subject them to an embargo of Southern cotton until they received recognition. While many Englishmen were offended by Seward’s bluster, many “resented even more the Confederacy’s attempt at economic blackmail.” [32]

The British especially were keen on not going to war for the sake of the South, there was far too much at stake for them. This was something that the Southern leaders and representatives did not fully comprehend. Prime Minister Viscount Palmerston and Foreign Minister Lord Russell were concerned about the economic impact of the loss of Southern cotton but also “recognized that any action against the blockade could lead to a conflict with the United States more harmful to England’s interests than the temporary loss of Southern cotton.” [33] Palmerston well remembered the war of 1812 when he served as Minister of War, and the disastrous results for the British Merchant Marine, and he realized that “England could not only afford the risk of a loss in a sideline war; she could not even afford to win one.” [34]

Dennis Hart Mahan the First American Military Theorist

The Development of American Military Culture and Theory

As we examine the Civil War as the first modern war we have to see it as a time of great transition and change for military and political leaders. As such we have to look at the education, culture and experience of the men who fought the war, as well as the various advances in technology and how that technology changed tactics which in turn influenced the operational and strategic choices that defined the characteristics of the Civil War and wars to come.

The leaders who organized the vast armies that fought during the war were influenced more than military factors. Social, political, economic, scientific and even religious factors influenced their conduct of the war. The officers that commanded the armies on both sides grew up during the Jacksonian opposition to professional militaries, and for that matter even somewhat trained militias. The Jacksonian period impacted how officers were appointed and advanced. Samuel Huntington wrote:

“West Point was the principle target of Jacksonian hostility, the criticism centering not on the curriculum and methods of the Academy but rather upon the manner of how cadets were appointed and the extent to which Academy graduates preempted junior officer positions in the Army. In Jacksonian eyes, not only was specialized skill unnecessary for a military officer, but every man had the right to pursue the vocation of his choice….Jackson himself had an undisguised antipathy for the Academy which symbolized such a different conception of officership from that which he himself embodied. During his administration disciple faltered at West Point, and eventually Sylvanus Thayer, the superintendent and molder of the West Point educational methods, resigned in disgust at the intrusion of the spoils system.” [35]

This is particularly important because of how many officers who served in the Civil War were products of the Jacksonian system and what followed over the next two decades. Under the Jackson administration many more officers were appointed directly from civilian sources than from West Point, often based on political connections. “In 1836 when four additional regiments of dragoons were formed, thirty officers were appointed from civilian life and four from West Point graduates.” [36]

While this in itself was a problem it was made worse by a promotion system based on seniority, not merit. There was no retirement system so officers who did not return to the civilian world hung on to their careers until they quite literally died with their boots on. This held up the advancement outstanding junior officers who merited promotion and created a system where “able officers spent decades in the lower ranks, and all officers who had normal or supernormal longevity were assured of reaching higher the higher ranks.” [37]

Robert E. Lee was typical of many officers who stayed in the Army. Despite his success he was haunted by his lack of advancement. While still serving in Mexico having gained great laurels including a brevet promotion to Lieutenant Colonel, but “the “intrigues, pettiness and politics…provoked Lee to question his career.” He wrote “I wish I was out of the Army myself.” [38] In 1860 on the brink of the war Lee was “a fifty-three year-old man and felt he had little to show for it, and small hope for promotion.” [39] Lee’s discouragement was not unwarranted, despite his exemplary service there was little hope for promotion and to add to it Lee knew that “of the Army’s thirty-seven generals from 1802 to 1861, not one was a West Pointer.” [40] Other exemplary officers including Winfield Scott Hancock languished with long waits for promotion between the Mexican War and the Civil War. The long waits for promotion and duty in often desolate duty stations separated from family caused many officers to leave the Army; a good number of whom in 1861 became prominent in both the Union and Confederate armies. Among these officers were such notables as Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, Henry Halleck, George McClellan and Jubal Early.

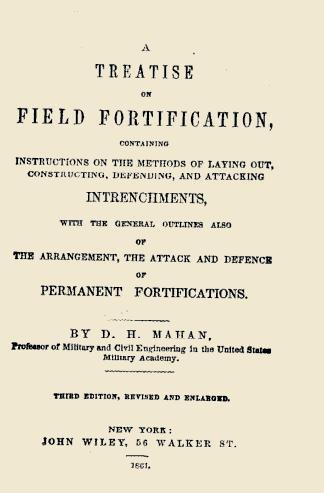

The military education of these officers at West Point was based on the Napoleonic tactics and methods espoused by Henri Jomini as Clausewitz’s works had yet to make their way to America. Most were taught by Dennis Hart Mahan. Mahan, who graduated at the top of the West Point class of 1824 and spent four years in France as a student and observer at the “School of Engineering and Artillery at Metz” [41] before returning to the academy where “he was appointed professor of military and civil engineering and of the science of war.” [42]

In France Mahan studied the prevailing orthodoxy of Henri Jomini who along with Clausewitz was the foremost interpreter of Napoleon and the former Chief of Staff of Marshal Ney. Jomini’s influence cannot be underestimated, some have noted, a correctly so that “Napoleon was the god of war and Jomini was his prophet.” [43]

The basic elements of Jominian orthodoxy were that: “Strategy is the key to warfare; That all strategy is controlled by invariable scientific principles; and That these principles prescribe offensive action to mass forces against weaker enemy forces at some defensive point if strategy is to lead to victory.” [44] Jomini interpreted “the Napoleonic era as the beginning of a new method of all out wars between nations, he recognized that future wars would be total wars in every sense of the word.” [45] Jomini laid out a number of principles of war including elements that we know well today, operations on interior and exterior lines, bases of operations, and lines of operation. He understood the importance of logistics in war, envisioned the future of amphibious operations and his thought would be taken to a new level by Alfred Thayer Mahan, the son of Dennis Hart Mahan in his book The Influence of Sea Power on History.

Jomini also foresaw the horrific nature of the coming wars and expressed his revulsion for them and desire to return to the limited wars of the eighteenth century:

“I acknowledge that my prejudices are in favor of the good old times when the French and English guards courteously invited each other to fire first as at Fontenoy, preferring them to the frightful epoch when priests, women. And children throughout Spain plotted the murder of individual soldiers.” [46]

Jomini’s influence was great throughout Europe and was brought back to the United States by Mahan who principally “transmitted French interpretations of Napoleonic war” [47]including that of Jomini. However, Mahan returned from France somewhat dissatisfied knowing that much of what he learned was impractical in the United States where a tiny professional army and the vast expenses of territory were nothing like European conditions. Mahan thought prevailing doctrine “was acceptable for a professional army on the European model, organized and fighting under European conditions. But for the United States, which in case of war would have to depend upon a civilian army held together by a small professional nucleus, the French tactical system was unrealistic.” [48]

Mahan set about rectifying this immediately upon his return and though “steeped in French thought, but acutely sensitive to American conditions that in his lectures and later writings he modified “the current orthodoxy by rejecting one of its central tenants-primary reliance on offensive assault tactics.” [49] Mahan believed that “ If the offensive is attempted against a strongly positioned enemy, Mahan cautioned, it should be an offensive not of direct assault but of the indirect approach, of maneuver and deception. Victories should not be purchased by the sacrifice of one’s own army….To do the greatest damage to our enemy with the least exposure of ourselves,” said Mahan, “is a military axiom lost sight of only by ignorance to the true ends of victory.” [50] However, “so strong was the attraction of Napoleon to nineteenth-century soldiers that American military experience, including the generalship of Washington, was almost ignored in military studies here.” [51]

Thus there was a tension in American military thought between the followers of Jomini and Mahan. Conservative Jominian thinking predominated much of the Army, and within the army “Mahan’s decrees failed to win universal applause.” [52] This may have been due in part to the large number of officers accessed directly from civilian life during the Jacksonian period. Despite this it was Mahan who more than any other “taught the professional soldiers who became the generals of the Civil War most of what they knew through the systematic study of war.” [53]

Mahan’s influence on the future leaders of the Union and Confederate armies went beyond the formal classroom setting. Mahan established the “Napoleon Club,” a military round table at West Point.[54] Mahan dominated the academy in many ways, and for the most part he ran the academic board, which ran the academy, and “no one was more influential than Mahan in the transition of officership from a craft into a profession.” [55] Mahan was a unique presence at West Point who all students had to face in their final year. Mahan was:

“aloof and relentlessly demanding, he detested sloppy thinking, sloppy posture, and a sloppy attitude toward duty…Mahan would demand that they not only learn engineering and tactics, but that every manner and habit that characterizes an officer- gentlemanly deportment, strict integrity, devotion to duty, chivalric honor, and genuine loyalty- be pounded into them. His aim was to “rear soldiers worthy of the Republic.” [56]

Mahan’s greatest contributions in for American military doctrine were his development of the active defense and emphasis on victory through maneuver. Mahan stressed “swiftness of movement, maneuver, and use of interior lines of operation. He emphasized the capture of strategic points instead of the destruction of enemy armies,” [57] while he emphasized the use of “maneuver to occupy the enemy’s territory or strategic points.” [58]

That being said Mahan’s “greatest contribution to American military professionalism was, in all probability, his stress upon the lessons to be learned from history. Without “historical knowledge of the rise and progress” of the military art, he argued, it is impossible to get “even tolerably clear elementary notions” beyond “the furnished by mere technical language…It is in military history that we are able to look for the source of all military science.” [59] Mahan emphasized that “study and experience alone produce the successful general” noting “Let no man be so rash as to suppose that, in donning a general’s uniform, he is forthwith competent to perform a general’s function; as reasonably he might assume that in putting on robes of a judge he was ready to decide any point of the law.” [60] Such advice is timeless.

Mahan certainly admired Napoleon and was schooled in Jomini, but he believed that officers needed to think for themselves on the battlefield. And “no two things in his military credo were more important than the speed of movement- celerity, that secret of success- or the use of reason. Mahan preached these twin virtues so vehemently and so often through his chronic nasal infection that the cadets called him “Old Cobbon Sense.” [61] Like Jomini, Mahan was among the first to differentiate between strategy, which involved “fundamental, invariable principles, embodied what was permanent in military science, while tactics concerned what was temporary….and “the line which distinguishes one from another is “that which separates the science from the art.” [62]

Henry Wager Halleck

Mahan’s teaching was both amplified and modified by the work of his star pupil Henry Wager Halleck wrote the first American textbook on military theory Elements of Military Art and Science which was published in 1846 and though it was not a standard text at West Point “it was probably the most read book among contemporary officers.” [63] The text was based on a series of twelve lectures Halleck had given the Lowell Institute in 1845, as Halleck was considered one of America’s premier scholars.

Like Mahan, Halleck was heavily influenced by the writings of Jomini, and the Halleck admitted that his book “was essentially a compilation of other author’s writings,” [64] including those of Jomini and Mahan; and he “changed none of Mahan’s and Jomini’s dogmas.” [65] In addition to his own book, Halleck also “translated Jomini’s Life of Napoleon” from the French. [66] Halleck, like his mentor Mahan “recognized that the defense was outpacing the attack” [67] in regard to how technology was beginning to change war and “five of the fifteen chapters in Halleck’s Elements are devoted to fortification; a sixth chapter is given over to the history and importance of military engineers.” [68] Halleck’s Elements became one of the most influential texts on American military thought during the nineteenth century, and “had a major influence on American military thought” [69] being read by many before, during and after the war, including Abraham Lincoln.

Halleck, as a part of Mahan’s enlightenment too fought against the Jacksonian wave, eloquently speaking out for a more professional military against the Jacksonian critics. Halleck plead “for a body of men who shall devote themselves to the cultivation of military science” and the substitution of Prussian methods of education and advancement for the twin evils of politics and seniority.” [70]

As we look the Gettysburg campaign it is important to note how much of Mahan’s teaching either shows up in the actions of various commanders, such as Meade’s outstanding use of interior lines on the defense; or how in some cases his advice, particularly on attacking strongly held positions was ignored by Lee. In fairness to Lee he “was the only principle general of the war who had attended West Point too early to study the military art under Dennis Mahan.” [71] Likewise, during his tenure as the Superintendent of West Point Lee had little time to immerse himself in new studies due to the changes being wrought at the Academy in terms of discipline and curriculum. If anything can be said about Lee was that he was much more affected by what he read about Napoleon’s battles and campaigns; in which he took a lifelong interest in while a cadet, reading the French editions of the “three volumes of General Montholon’s memoirs of Napoleon dealing with the early campaigns, and the first volume of General Segur’s Expedition de Russie dealing with Napoleon’s advance to Moscow in 1812” [72] than he was with Jomini’s theories, though he certainly would have had some familiarity with them. Lee continued his study of Napoleon’s campaigns during his time as superintendent of West Point, in which “of fifteen books on military subjects that he borrowed from the academy library during his superintendency, no more than seven concerned Napoleon.” [73] Lee’s studies of the emperor’s campaigns allowed him to draw “more aggressive strategic concepts that previous American generals” [74] concepts that he would execute with alacrity during his campaigns of 1862 and 1863.

While West Point was the locus of American military thought and professionalism there was in the South a particular interest in military thought and this “was manifest in the creation of local military schools. Virginia Military Institute was established in 1839, the Citadel and the Arsenal set up in South Carolina in 1842, Kentucky Military Institute in 1845. By 1860 every Southern state, except Texas and Florida, had its own state supported military academy patterned on the models of West Point and VMI.” [75] There was no such development in the North, making these schools a unique part of the American military heritage, only some of which remain.

As the American theorists began their period of enlightenment, there was no real corresponding development in tactical doctrine, in part because “in Europe almost all the tactical experience of the major armies seemed to bear Jomini out.” [76] The American Army lacked “an integrated tactical system for infantry, artillery and cavalry doctrine” [77] which showed up frequently during the Civil War as commanders struggled to adapt tactics to advances in weaponry. The events in Europe, “all seemed to testify that it was the army on offense that won European battles, and at lightning speed.” [78] As such there existed an “ambivalence of thinking on the merits of the offense versus the defense in infantry tactics….while American artillery doctrine firmly subordinated the artillery to the infantry” [79] as many American officers were convinced that this was the face of war and all the major infantry tactics handbooks “borrowed heavily from Napoleonic sources and stressed the virtue of quick, aggressive movements on the battlefield.” [80] The often disjointed developments in infantry, artillery and cavalry tactics of the ante-bellum Army demonstrated that “Military thinking, and even more strategic organization, remained essentially within the Napoleonic tradition filtered through an eighteenth-century world view….” [81] It would take the bloody experience of war to change them. As Fuller noted that “the tactics of this war were not discovered through reflection, but through trial and error.” [82]

To be continued….

Notes

[1] Clausewitz, Carl von. On War Indexed edition, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976 p.75

[2] Fuller, J.F.C. The Conduct of War 1789-1961 Da Capo Press, New York 1992. Originally published by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick N.J p.99

[3] Gray, Colin S. Fighting Talk: Forty Maxims on War, Peace, and Strategy Potomac Book, Dulles VA 2009 p.36

[4] Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.36

[5] Fuller, J.F.C. A Military History of the Modern World, Volume Three: From the Seven Days Battle, 1862, to the Battle of Leyte Gulf, 1944 Minerva Press 1956 p.88

[6] Ibid. Fuller A Military History of the Modern World, Volume Three p.88

[7] Flood, Charles Bracelen, Grant and Sherman: The Friendship that Won the War, Harper Perennial, New York 2005 p.238

[8] Ibid. Clausewitz p.90

[9] McPherson, James. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1988 p.809

[10] Weigley, Russell F. The American Way of War: A History of United States Military History and Policy University of Indiana Press, Bloomington IN, 1973 p.149

[11] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.558

[12] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.857

[13] Ibid. Fuller The Conduct of War 1789-1961 p.99

[14] Fuller has an excellent synopsis of this in his book A Military History of the Modern World, Volume Three (p.89). He wrote: The war fought by Grant and Lee, Sherman and Johnston, and others closely resembled the First of the World Wars. No other war, not even the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, offers so exact a parallel. It was a war of rifle bullets and trenches, of slashings, abattis, and even of wire entanglements- an obstacle the Confederates called “a devilish contrivance which none but a Yankee could devise” because at Drewry’s Bluff they had been trapped in them and slaughtered like partridges.” It was a war of astonishing in its modernity, with wooden wire-bound mortars hand and winged grenades, rockets, and many forms of booby traps. Magazine rifles and Requa’s machine guns were introduced and balloons were used by both sides although the confederates did not think much of them. Explosive bullets are mentioned and also a flame projector, and in June, 1864, General Pendleton asked the chief ordnance officer at Richmond whether he could supply him with “stink-shells” which would give off “offensive gases” and cause “suffocating effect.” The answer he got was “stink-shells, none on hand; don’t keep them; will make them if ordered.” Nor did modernity end there; armoured ships, armoured trains, land mines and torpedoes were used. A submarine was built by Horace H. Hundley at Mobile….”

[15] Ibid. Fuller A Military History of the Modern World, Volume Three p.89

[16] Ibid. Clausewitz On War p.89

[17] Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.38

[18] Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.5

[19] Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.3

[20] Ibid. Clausewitz On War p.89

[21] ________ JCWS Student Text 1 3rd Edition, 14 June 2013 p.2-4

[22] Guelzo Allen C. Fateful Lightening: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2012

[23] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.857

[24] Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.38

[25] Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.38

[26] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.391

[27] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.154

[28] Ibid. Foote , The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.153

[29] Ibid. Foote , The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.153

[30] Ibid. Foote , The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.155

[31] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.391

[32] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.384

[33] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.384

[34] Ibid. Foote , The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.154

[35] Huntington, Samuel P. The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 1957 pp.204-205

[36] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.206

[37] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.207

[38] Thomas, Emory Robert E. Lee W.W. Norton and Company, New York and London 1995 p.139

[39] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.213

[40] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.207

[41] Hagerman, Edward. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare Midland Book Editions, Indiana University Press. Bloomington IN. 1992. p.7

[42] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.7

[43] Hittle, J.D. editor Jomini and His Summary of the Art of War a condensed version in Roots of Strategy, Book 2 Stackpole Books, Harrisburg PA 1987 p. 429

[44] Shy, John Jomini in Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age edited by Paret, Peter, Princeton University Press, Princeton New Jersey 1986 p.146

[45] Ibid. Hittle, Jomini and His Summary of the Art of War p. 428

[46] Ibid. Hittle Jomini p.429

[47] Ibid. Shy Jomini p.414

[48] bid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.7

[49] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.9

[50] Ibid. Weigley The American Way of War p.88

[51] Ibid. Shy Jomini p.414

[52] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.13

[53] Ibid. Shy Jomini p.414

[54] Hagerman also notes the contributions of Henry Halleck and his Elements of Military Art and Science published in 1846 (p.14) and his influence on many American Officers. Weigley in his essay in Peter Paret’s Makers of Modern Strategy would disagree with Hagerman who notes that in Halleck’s own words that his work was a “compendium of contemporary ideas, with no attempt at originality.” (p.14) Weigley taking exception gives credit to Halleck for “his efforts to deal in his own book with particularly American military issues.” Paret, Peter editor. Makers of Modern Strategy: For Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1986 p.416.

[55] Millet, Allan R. and Maslowski, Peter, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States The Free Press a Division of Macmillan Inc. New York, 1984 p.126

[56] Waugh, John C. The Class of 1846: From West Point to Appomattox, Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan and their Brothers Ballantine Books, New York 1994 pp.63-64

[57] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p.30

[58] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.14

[59] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.220

[60] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State pp.221

[61] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.64

[62] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State pp.220-221

[63] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.14

[64] Marszalek, John F. Commander of All of Lincoln’s Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 2004 p.42

[65] Ambrose, Stephen E. Halleck: Lincoln’s Chief of Staff Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London 1962 p.6

[66] Weigley, Russell F. American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War. In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age edited by Paret, Peter, Princeton University Press, Princeton New Jersey 1986 p.416

[67] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.14

[68] Ibid. Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War. In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.417

[69] Ibid. Ambrose Halleck p.7

[70] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.221

[71] Ibid. Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War. In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.415

[72] Ibid. Korda, Clouds of Glory p.35

[73] Ibid. Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War. In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.424

[74] Ibid. Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War. In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.424

[75] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.219

[76] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lighteningp.147

[77] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.20

[78] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lighteningp.147

[79] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare pp.20-21

[80] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lighteningp.147

[81] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.27

[82] Ibid. Fuller. Grant and Lee p.269 A similar comment might be made of most wars including the war in Iraq current Afghanistan war.