Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

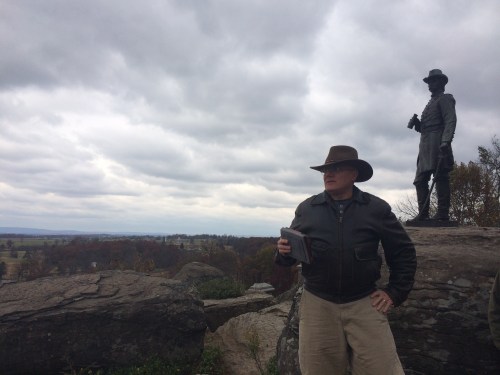

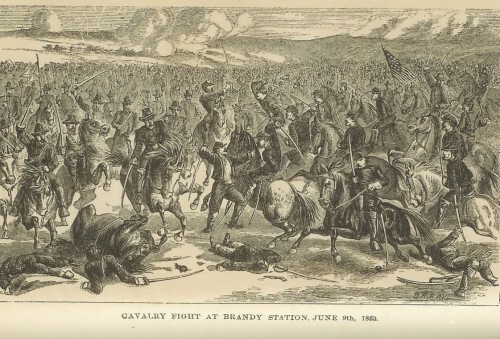

Today I take a look back at the battle of Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle every fought on the North American continent. This is a section of my draft Gettysburg campaign text.

Have a great day,

Peace

Padre Steve+

Movement to attain operational reach and maneuver are two critical factors in joint operations. In the time since the American Civil War the distances that forces move to engage the enemy, or maneuver to employ fires to destroy his forces have greatly increased. Movement may be part of an existing Campaign Plan or Contingency Plan developed at Phase 0; it also may be part of a crisis action plan developed in the midst of a campaign. Lee’s movement to get to Gettysburg serves as an example of the former, however, since his forces were already in contact with the Army of the Potomac along the Rappahannock and he was reacting to what he felt was a strategic situation that could not be changed but by going on the offensive that it has the feel of a Crisis Action Plan. Within either context other factors come into play: clarity of communications and orders, security, intelligence, logistics and even more importantly the connection between operational movement and maneuver; the Center of Gravity of the enemy, and national strategy. Since we have already discussed how Lee and the national command authority of the Confederacy got to this point we will now discuss the how that decision played in the operational and tactical decisions of Lee and his commanders as the Army of Northern Virginia began the summer campaign and the corresponding actions of Joseph Hooker and the his superiors in Washington.

“One of the fine arts of the military craft is disengaging one’s army from a guarding army without striking sparks and igniting battle.” [1] On June 3rd 1863 Robert E. Lee began to move his units west, away from Fredericksburg to begin his campaign to take the war to the North. He began his exfiltration moving Second Corps under Richard Ewell and First Corps under James Longstreet west “up the south bank of the Rappahannock to Culpepper, near which Hood and Pickett had been halted on their return from Suffolk.” [2] Rodes’ division of Second Corps followed on June 4th with Anderson and Early on June 5th. Lee left the three divisions of A.P. Hill’s Third Corps at Fredericksburg to guard against any sudden advance by Hooker’s Army of the Potomac toward Richmond. Lee instructed Hill to “do everything possible “to deceive the enemy, and keep him in ignorance of any change in the disposition of the army.” [3]

The army was tremendously confident as it marched away from the war ravaged, dreary and desolate battlefields along the Rappahannock “A Captain in the 1st Virginia averred, “Never before has the army been in such a fine condition, so well disciplined and under such complete control.” [4] Porter Alexander wrote that he felt “pride and confidence…in my splendid battalion, as it filed out of the field into the road, with every chest & and ammunition wagon filled, & and every horse in fair order, & every detail fit for a campaign.” [5] Another officer wrote to his father, “I believe there is a general feeling of gratification in the army at the prospect of active operations.” [6]

Lee’s plan was to “shift two-thirds of his army to the northwest and past Hooker’s flank, while A.P. Hill’s Third Corps remained entrenched at Fredericksburg to observe Hooker and perhaps fix him in place long enough for the army to gain several marches on the Federals.” [7] In an organizational and operational sense that Lee’s army after as major of battle as Chancellorsville “was able to embark on such an ambitious flanking march to the west and north around the right of the army of the Potomac….” [8]

However, Lee’s movement did not go unnoticed; Hooker’s aerial observers in their hot air balloons “were up and apparently spotted the movement.” [9] But Hooker was unsure what it meant. He initially suspected that “Lee intended to turn the right flank of the Union army as he had done in the Second Bull Run Campaign, either by interposing his army between Washington and the Federals or by crossing the Potomac River.” [10] Lee halted at Culpepper from which he “could either march westward over the Blue Ridge or, if Hooker moved, recontract at the Rappahannock River.” [11]

Hooker telegraphed Lincoln and Halleck on June 5th and requested permission to advance cross the river and told Lincoln that “I am of opinion that it is my duty to pitch into his rear” [12] possibly threatening Richmond. Lincoln ordered Hooker to put the matter to Halleck, with whom Hooker was on the worst possible terms. Hooker “pressed Halleck to allow him to cross the Rappahannock in force, overwhelming whatever rebel force had been left at Fredericksburg, and then lunging down the line of the Virginia Central toward an almost undefended Richmond.” [13] On the morning of June 6th Hooker ordered pontoon bridges thrown across the river and sent a division of Sedgwick’s VI Corps to conduct a reconnaissance in force against Hill.

Lincoln and Halleck immediately rejected Hooker’s request. Lincoln “saw the flaw in Hooker’s plan at once” [14] and replied in a very blunt manner: “In one word,” he wrote “I would not take any risk of being entangled upon the river, like an ox jumped half over a fence and liable to be torn by dogs front and rear, without a fair chance to gore one way or kick another.” [15] Halleck replied to Hooker shortly after Lincoln that it would “seem perilous to permit Lee’s main force to move upon the Potomac [River] while your army is attacking an intrenched position on the other side of the Rappahannock.” [16] Lincoln, demonstrating a keen regard for the actual center of gravity of the campaign, told Hooker plainly that “I think Lee’s army and not Richmond, is your objective point.” [17]

The fears of Lincoln and Halleck were well founded. In stopping at Culpepper Lee retained the option of continuing his march to the Shenandoah and the Potomac, or he could rapidly “recall his advanced columns, hammer at Hooker’s right flank, and very possibly administer another defeat even more demoralizing than the one he suffered at Chancellorsville.” [18] Hooker heeded the order and while Hooker maintained his bridgehead over the Rappahannock he made no further move against Hill’s well dug in divisions.

Meanwhile, J.E.B. Stuart and his Cavalry Corps had been at Brandy Station near Culpepper for two weeks. Culpepper in June was a paradise for the cavalry, and with nearly 10,000 troopers gathered Stuart ordered a celebration, many dignitaries were invited and on June 4th Stuart hosted a grand ball in the county courthouse. On the 5th Stuart staged a grand review of five of his brigades. Bands played as each regiment passed in review and one soldier wrote that it was “One grand magnificent pageant, inspiring enough to make even an old woman feel fightish.” [19] The review ended with a mock charge by the cavalry against the guns of the horse artillery which were firing blank rounds. According to witnesses it was a spectacular event, so realistic and grand that during the final charge that “several ladies fainted, or pretended to faint, in the grandstand which Jeb Stuart had had set up for them along one side of the field.” [20] That was followed by an outdoor ball “lit by soft moonlight and bright bonfires.” [21] Stuart gave an encore performance when Lee arrived on June 8th, minus the grand finale and afterward Lee wrote to his wife that “Stuart was in all his glory.” [22]

Hooker received word from the always vigilant John Buford, of the First Cavalry Division on the night of June 6th that “Lee’s “movable column” was located near Culpepper Court House and that it consisted of Stuart’s three brigades heavily reinforced by Robertson’s, “Grumble” Jones’s, and Jenkins’ brigades.” [23] Hooker digested the information and believed that Stuart’s intent was to raid his own rear areas to disrupt the Army of the Potomac’s logistics and communications. The next day Hooker ordered his newly appointed Cavalry Corps Commander, Major General Alfred Pleasanton to attack Stuart.

After Chancellorsville, Hooker had reorganized the Union cavalry under Pleasanton into three divisions and under three aggressive division commanders, all West Pointers, Brigadier General John Buford, Brigadier General David Gregg and Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick. While Stuart conducted his second grand review for Lee Pleasanton quietly massed his cavalry “opposite Beverly Ford and Kelly’s Ford so as to cross the river in the early morning hours of June 9th and carry out Hooker’s crisp orders “to disperse and destroy” the rebel cavalry reported to be “assembled in the vicinity of Culpepper….” [24] Pleasanton’s cavalry was joined by two mixed brigades of infantry “who had the reputation of being among the best marchers and fighters in the army.” [25] One brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Adelbert Ames consisted of five regiments drawn from XI Corps, XII Corps, and III Corps was attached to Buford’s division. The other brigade, under the command of Brigadier General David Russell was composed of seven regiments drawn from I Corps, II Corps and VI Corps. [26]

Stuart’s orders for June 9th were to “lead his cavalry division across the Rappahannock to screen the northward march of the infantry.” [27] The last thing that Stuart expected was to be surprised by the Federal cavalry which he had grown to treat with distain. Stuart who was at his headquarters “woke to the sound of fighting” [28] as Pleasanton’s divisions crossed the river and moved against the unsuspecting Confederate cavalry brigades.

The resultant action was the largest cavalry engagement of the war. Over 20,000 troopers engaged in an inconclusive see-saw battle that lasted most of the day. Though a draw “the rebels might have been swept from the field had Colonel Alfred N. Duffie, at the head of the Second Division acted aggressively and moved to the sounds of battle.” [29] The “Yankees came with a newfound grit and gave as good as they took.” [30] Porter Alexander wrote that Pleasanton’s troopers “but for bad luck in the killing of Col. Davis, leading the advance, would have probably surprised and captured most of Stuart’s artillery.” [31] Stuart had lost “over 500 men, including two colonels dead,” [32] and a brigade commander, Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee, General Lee’s son, badly wounded. While recuperating at his wife’s home a few weeks later Lee “was captured by the enemy.” [33] Stuart claimed victory as he lost fewer troops and had taken close to 500 prisoners and maintained control of the battlefield.

But even Confederate officers were critical. Lafayette McLaws of First Corps wrote “our cavalry were surprised yesterday by the enemy and had to do some desperate fighting to retrieve the day… As you will perceive from General Lee’s dispatch that the enemy were driven across the river again. All this is not true because the enemy retired at their leisure, having accomplished what I suppose what they intended.” [34] Captain Charles Blackford of Longtreet’s staff wrote: “The fight at Brandy Station can hardly be called a victory. Stuart was certainly surprised, but for the supreme gallantry of his subordinate officers and men… it would have been a day of disaster and disgrace….” The Chief of the Bureau of War in Richmond, Robert H.G. Kean wrote “Stuart is so conceited that he got careless- his officers were having a frolic…” [35] Brigadier General Wade Hampton had the never to criticize his chief in his after action report and after the war recalled “Stuart managed badly that day, but I would not say so publicly.” [36]

The Confederate press was even more damning in its criticism of Stuart papers called it “a disastrous fight,” a “needless slaughter,” [37]and the Richmond Examiner scolded Stuart in words that cut deeply into Stuart’s pride and vanity:

“The more the circumstances of the late affair at Brandy Station are considered, the less pleasant do they appear. If this was an isolated case, it might be excused under the convenient head of accident or chance. But the puffed up cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia has twice, if not three times, surprised since the battles of December, and such repeated accidents can be regarded as nothing but the necessary consequences of negligence and bad management. If the war was a tournament, invented and supported for the pleasure of a few vain and weak-headed officers, these disasters might be dismissed with compassion, But the country pays dearly for the blunders which encourage the enemy to overrun and devastate the land, with a cavalry which is daily learning to despise the mounted troops of the Confederacy…” [38]

But the battle was more significant than the number of casualties inflicted or who controlled the battlefield at the end of the day. Stuart had been surprised by an aggressively led Union Cavalry force. The Union troopers fought a stubborn and fierce battle and retired in good order. Stuart did not appreciate it but the battle was a watershed, it ended the previous dominance of the Confederate Cavalry arm. It was something that in less than a years’ time would cost him his life.

Notes

[1] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg, Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 2003 p.59

[2] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.436

[3] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.25

[4] Wert, Jeffry D. A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2011 p.218

[5] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p.221

[6] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.219

[7] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.60

[8] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.530

[9] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.436

[10] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.260

[11] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.37

[12] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.61

[13] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.50

[14] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.260

[15] Fuller, J.F.C. Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2007 copyright 1942 The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals p.223

[16] Ibid Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.26

[17] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.50

[18] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.53

[19] Davis, Burke J.E.B. Stuart: The Last Cavalier Random House, New York 1957 p.304

[20] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.437

[21] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.63

[22] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.221

[23] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.54

[24] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.64

[25] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.54

[26] Petruzzi, J. David and Stanley, Steven The Gettysburg Campaign in Numbers and Losses: Synopses, Orders of Battle, Strengths, Casualties and Maps, June 9 – July 1, 1863 Savas Beatie LLC, El Dorado Hills CA 2012 p.7

[27] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.64

[28] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.306

[29] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.261

[30] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p. 251

[31] Ibid. Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy p.223

[32] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.310

[33] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.221

[34] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.59

[35] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.310

[36] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.60

[37] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.57

[38] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.311-312