Friends of Padre Steve’s World

The latest major chapter revision to my Gettysburg text, this one about the opening of the battle and two men, Confederate Major General Harry Heth and Union Major General John Buford whose actions that morning set in motion the greatest battle ever fought on the American Continent.

Peace

Padre Steve+

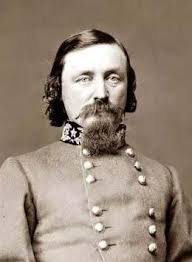

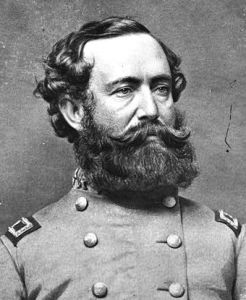

The principles found in Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff’s “Desired Leader Attributes” are something that we can learn about from both practical experience and history. The study of commanders and leaders throughout the Gettysburg campaign provide historical examples of commanders and other leaders that the best and the worst examples of some of those concepts. One of these is the ability to “anticipate and adapt to surprise and uncertainty.” The meeting engagement on the morning of July 1st 1863 between Harry Heth’s division of A.P. Hill’s corps and John Buford’s First Cavalry Division shows a very clear example of a commander, Heth, not anticipating or adapting to surprise and uncertainty. Heth was surprised by the presence of experienced Federal cavalry on his front and the uncertainty of not knowing what lay just beyond McPherson and Seminary Ridge.

Despite the warnings of Brigadier General Johnston Pettigrew, Major General Harry Heth and his corps commander Lieutenant General A.P. Hill decided that they would advance into Gettysburg. Hill and Heth dismissed Pettigrew’s warnings out of hand. Pettigrew should have been listened to, he was “was one of those natural leaders of a privileged background who, without military ambitions, had been advanced on the application of native intelligence and contagious courage.” [1] To help state his case Pettigrew brought Captain Louis G. Young of his staff, who had served under Hill and was a professional soldier “with the hope that his testimony as to Union numbers might be more convincing.” [2] Young “insisted that the troops he saw were veterans rather than Home Guards,” [3] but Hill refused to believe telling Young and Pettigrew “I still cannot believe that any portion of the Army of the Potomac is up,” he declared. Then he added: “I hope that it is, for this is the place I want it to be.” [4] Hill told Heth and Pettigrew that “I am just from General Lee, and the information he has from his scouts corroborates what I have received from mine – that is, the enemy is still at Middleburg and have not yet struck their tents.” [5]

How Hill could make such a statement neither knowing the ground nor the location and strength of the Federal troops to his front is stunning. How Hill’s “scouts” could miss the massive force heading their way is beyond belief and indicates that Hill wanted to believe what he wanted to believe and disregarded any evidence to the contrary, especially that which came from a subordinate that he did not know who was not a professional soldier. Hill’s attitude also demonstrates the profound lack of respect given to the Army of the Potomac by Hill and many other Confederate commanders.

Hill sent a message to Lee, as well as Ewell of Second Corps telling them that “I intended to advance the next morning and discover what was in my front.” [6] He also sent word of the discovery of cavalry to Lee’s headquarters, but his warning apparently gave Lee little cause for concern as Lee believed that “Meade’s army was still some distance to the south.” [7] Likewise, Hill sent a courier to Richard Anderson instructing him to bring up his division on July 1st and instructed Heth that “Pender’s division also would be ordered through Cashtown as a reserve to be available if Heth ran into serious trouble.” [8]

During the night the actions of A.P. Hill show a commander who confused and uncertain. The confidence that he and Heth showed in rejecting Pettigrew and Young’s reports of Federal troops in Gettysburg had left “most, if not all the commanding officers in Hill’s corps…unprepared for what happened.” [9] Lieutenant Lewis Young wrote “I doubt if any of the commanders of brigades, except General Pettigrew, believed that we were marching to battle, a weakness on their part which rendered them unprepared for what was about to happen.” [10]

A major part of Hill’s uncertainly can be laid on his and his subordinate commander’s lack of experience at their current level of command. “Pettigrew new to the army, Heth to division command, and Hill to corps command.” [11] One could not ask for such an untested chain-of-command as the army advanced blindly forward not knowing what lay before it. James Longstreet said “The army…moved forward, as a man might walk over strange ground with his eyes shut.” [12]

Lieutenant Colonel Porter Alexander noted that on the night of June 30th that he visited Lee’s headquarters and found conversation to be “unusually careless & jolly. Certainly there was no premonition that the next morning was to open a great battle of the campaign.” [13] The attitude that all exhibited according to Alexander was “when all our corps were together what could successfully attack us? So naturally we were all in good spirits.” [14] The Confederates believed that they were invincible. Walter Taylor of Lee’s staff admitted “An overweening confidence possessed us all.” [15] Clifford Dowdey wrote:

“Considering their unprecedented assignment to act, in the absence of cavalry, as reconnaissance troops in a country they had never seen, the men were unrealistically relaxed – from the privates of the 1st South Carolina, the oldest unit in point of organization, to the corps commander.” [16]

The British observer, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle wrote in his diary: “The universal feeling in the army was one of profound contempt for an enemy whom they had beaten so consistently, and under so many disadvantages.” [17] That contempt would cost Lee’s army dearly in the coming battle.

Harry Heth arose on the morning of July 1st 1863 and formed his division for its march to Gettysburg. He had been ordered by Hill to “be ready to march at 5:00 A.M; and by an unusual directive from the corps commander, each man who wanted an issue of whisky at that early hour was to receive one.” [18] Heth should have spent the night making detailed plans for his advance but since neither he, nor any other senior officer in Hill’s corps “anticipated real action in the immediate area, Harry Heth kept uppermost in his mind the quartermaster aspects of the invasion,” [19] thus his overriding concern to get the shoes that supposedly were there in abundance, rather than “all the little details involved in an operation as tricky as a reconnaissance in force.” [20] The lack of attention to detail became evident the first thing that morning and that brought about an inauspicious start to a very bad day for Heth and his division. His troops were up early with the sunrise but somehow orders had not gotten to them to begin the advance at 5 a.m. and as a result “there was haste to the early morning’s preparations that caught some off guard” even regimental commanders. [21]

Several critics have made this point, among them Major John Mosby, the Confederate cavalry leader and guerrilla fighter who wrote: “Hill and Heth in their reports, to save themselves from censure, call the first day’s action a reconnaissance; this is all an afterthought….They wanted to conceal their responsibility for the defeat.” [22] A more contemporary writer, Jennings Wise, noted that Hill’s orders “were specific not to bring on an action, but his thirst for battle was unquenchable, and…he rushed on, and…took the control of the situation out of the hands of his commander-in-chief.” [23]

Years later Heth made an unsubstantiated claim that “A courier came from Gen. Lee, with a dispatch ordering me to get those shoes even if I encountered some resistance.” [24] That appears unlikely as Mosby noted that no one ordered Hill to advance and Lee “would never have sanctioned it.” [25] The ever judicious Porter Alexander who had been in Lee’s headquarters the night of June 30th wrote that: “Hill’s movement to Gettysburg was made on his own accord, and with knowledge that he would find the enemy’s cavalry in possession.” [26]

The advance to contact was marred by Heth’s inexperience compounded by the illness of A.P. Hill which caused Hill to be absent at the critical point where contact was made with the Federal forces. Hill “awakened feeling very ill, too sick to mount his horse…although no diagnosis was made, he was probably suffering from overstrained nerves.” [27] While it is possible that Hill’s “malady could have been upset stomach, diarrhea, simple exhaustion or a flair up of the old prostate problem” [28] his history of illness at critical times throughout the war lends credence to the possibility that whatever he was suffering could have been brought about by his emotional state. The result was that Hill’s “disability made it impossible for him to assume personal responsibility on July 1, 1863.” [29]

Hill gave Heth the responsibility to lead the advance, not based on experience or command ability, but because his division was closest to Gettysburg. However, during the night Hill decided to augment Heth’s division by ordering Dorsey Pender’s division to support Heth, and thus committed two thirds of his corps to what was supposedly a reconnaissance mission to find shoes. Since a reconnaissance is normally conducted by small elements of one’s force, the fact that Hill committed his two divisions present to such a mission demonstrated his “own confusion and uncertainty” [30] regarding the nature of what he might face and to his own understanding of the mission that he was assigning Heth. Whatever Hill’s intentions “he ordered Pender to support Heth while he awaited Anderson in Cashtown.” [31]

Disregarding the only solid intelligence he had, Hill put the majority of his corps into a “reconnaissance” which he would not be able to lead, instead turning over command to Heth. Hill gave Heth strict instructions not to bring on an engagement. The admonition was clear: “Do not bring on an engagement.” [32]

Likewise it is distinctly possible that Heth, despite orders to the contrary “may have had more on his mind than shoes and information when he made his advance towards Gettysburg.” [33] This is the allegation of Confederate cavalryman John Singleton Mosby who: “charged Hill with planning a “foray” and calling it a “reconnaissance.” Both Hill and Heth, Mosby asserted “evidently expected to bag a few thousand Yankees, return to Cashtown, and present them to General Lee that evening. But…”they bit off more than they could chew.” [34] Mosby’s claim does lend some explanation as to why Hill committed such a large force to his “reconnaissance” however, since Hill was killed in the closing days of the war and because Mosby was a partisan of J.E.B. Stuart. Mosby’s claim, even if true cannot be verified. But the fact remains that Hill’s force “was too large for a reconnaissance mission…and too large of force to back away from any Yankee challenge.” [35]The result was that Hill’s large force “if opposed, might well commit Lee’s army to battle on a field that Lee had not seen and before his army was assembled.” [36]

Hill’s absence left Heth, an inexperienced division commander “without any sage counsel” [37] and Heth began to commit a series of costly errors. Hill’s instructions to Heth to aggressively execute the mission but at the same time to avoid a major action put his subordinate in a hard place that even more experienced commanders might have struggled to find the appropriate balance. However, Heth was not at the level of experience or battlefield savvy.

Heth stated after the war that he understood from Hill that his mission was a job that normally would be assigned to cavalry and the restraints that he was employ: “to ascertain what force was at Gettysburg, and if he found infantry opposed to him, to report the fact immediately, without forcing an engagement.” [38] However, when the action began Heth did not heed those instructions.

Heth advanced without the caution of a commander who had been told that enemy forces were likely opposing him. Even though Heth disbelieved the reports made by Pettigrew the previous day, some amount of judicious caution on his part should have been indicated. Instead, for reasons unknown Heth had his men advance as if it was a routine movement. “Rather than placing his strongest brigades in the lead, Heth simply determined order of march based on where the troops had bivouacked along the road the previous night.” [39]

Heth “pushed out his four brigades in routine deployment for contact. In taking elementary precautions, Heth gave no indication of sensing an impending clash of any consequence.” [40] He placed Archer’s veteran but depleted brigade and Davis’s newly organized and inexperienced brigade in the lead of the advance. They were accompanied by the division’s artillery battalion commanded by Major William Pegram. Behind the lead units came the brigades of Pettigrew and Brockenbrough.

It was a curious order of march, for it left Johnston’s Pettigrew’s brigade behind both Archer and Davis’s brigades despite the fact that it was closer to Gettysburg than any other brigade. Likewise it was the only unit in the division that had recent eyes on contact with the enemy and knew the ground and what was ahead of them. It is hard to understand why Heth did this but one can speculate that it might have been because of Pettigrew’s insistence of the type of Federal forces in their front the previous day which caused Heth to do this.

The attitude of the soldiers was good, but most of the soldiers and their leaders “assumed that this morning’s movement was simply one more part in the army’s overall concentration of forces” [41] and the troops many expected to meet were those of Ewell or Stuart, Colonel John Brockenbrough told the commander of the 55th Virginia that “we might meet some of Ewell’s command or Stuart’s.” [42] No one, with the possible exception of Johnston Pettigrew seemed to believe that experienced Federal troops lay before them, and Pettigrew had been ignored. This “spirit of unbelief” seemed to cloud the thinking of most, if not all of the commanding officers in Hill’s corps and left them unprepared for what happened.” [43]

Heth’s infantry brigades were deployed alongside the road and were led by several lines of skirmishers while the artillery battalion rumbled down the road between the infantry brigades, few expected any battle. Gunners from Pegram’s four-gun Fredericksburg battery leading his battalion’s advance recalled “We moved forward leisurely smoking and chatting as we rode along, not dreaming of the proximity of the enemy.” [44] Heth should have better anticipated the situation based on Pettigrew’s reports of the previous day and should have prepared his troops to expect combat. He demonstrated why one author called him “an intellectual lightweight.” [45] After the war when Heth told an officer from the Army of the Potomac “I did not know any of your people were north of the Potomac.” [46]

While Archer was highly experienced and had the advantage of commanding experienced veteran troops during this advance he was not well. Though he led his troops into combat “on that morning he was suffering from some debilitating ailment.” [47] The other commander leading the Confederate advance was the inexperienced Joseph Davis. Davis’s inexperience caused him to put the new and untested 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina in the van of his advance and left his veteran regiments the 2nd and 11th Mississippi in the rear guarding army stores. [48] It was an unfortunate choice, the 11th Mississippi was seasoned and had “fought with distinction” [49] as part of the Army of Northern Virginia over the previous year.

The advance of the brigades of Archer and Davis was uneventful until they reached Marsh Creek they encountered the cavalry vedettes or pickets of the 8th Illinois Cavalry of John Buford’s First Cavalry Division posted on the high ground just east of the creek. [50] Despite the fact that Pettigrew had repeatedly warned Heth and Hill about the presence of Union cavalry, the discovery of these forces was unanticipated by the Confederates leading the column. Early in the morning Pettigrew attempted to warn Archer of the topography of the area and the presence of Union troops. Lieutenant Young recorded that Pettigrew “told General Archer of a ridge some distance west of Gettysburg on which he would probably find the enemy, as this position was favorable for defense.” [51] Pettigrew also warned Archer of “a certain road which the Yankees might use to hit his flank, and the dangers of McPherson’s Ridge. Archer listened, believed not, marched on unprepared…” [52]

Enter John Buford

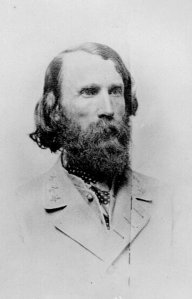

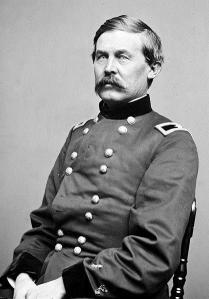

If Heth was inexperienced and knew little of the Federal forces arrayed before him and what forces were moving towards Gettysburg, his opponent Brigadier General John Buford was his opposite in nearly every respect. Buford was born in Kentucky and like Heth, came from a family with a long military history of military service, including family members who had fought in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. His family was well off with a spacious plantation near Versailles on which labored forty-five slaves, and his father also established a stage line which carried “passengers and freight between Frankfort and Lexington.” His father divested himself of his property, selling his home, business and presumably his slaves and moved to Stephenson Illinois in 1838. [53] The young Buford developed an interest in military life which was enlivened by his half-brother Napoleon Bonaparte Buford who graduated from West Point in 1827, and his brother would be influential in helping John into West Point, which he entered in 1844.

Buford graduated with the class of 1848 which included the distinguished Union artilleryman John Tidball, and the future Confederate brigadier generals William “Grumble” Jones, with whose troops he would do battle during the Gettysburg campaign and George “Maryland” Steuart. Among Buford’s best friends was Ambrose Burnside of the class of 1847. He did well academically but his conduct marks kept him from graduating in the top quarter of his class.

Upon graduation he was commissioned as a Brevet Second Lieutenant of Dragoons, however this came too late to serve in Mexico. Instead he was initially assigned to the First United States Dragoons but less than six months after joining was transferred to the Second Dragoons when he was promoted to full Second Lieutenant.

Instead of going to Mexico Buford “spent most of the 1850s tracking and fighting Indians on the Plains.” [54] During this period, the young dragoon served on the Great Plains against the Sioux, where he distinguished himself at the Battle of Ash Creek and on peacekeeping duty in the bitterly divided State of Kansas and in the Utah War of 1858.

His assignments alternated between field and staff assignments and he gained a great deal of tactical and administrative expertise that would serve him well. This was especially true in the realm of the tactics that he would employ so well at Gettysburg and on other battlefields against Confederate infantry and cavalry during the Civil War. Buford took note of the prevailing tactics of the day which still stressed a rigid adherence to outdated Napoleonic tactics which stressed mounted charges and “little cooperation with units of other arms or in the taking and holding of disputed ground.” [55] While he appreciated the shock value of mounted charges against disorganized troops he had no prejudice against “fighting dismounted when the circumstances of the case called for or seemed to justify it.” [56] Buford’s pre-war experience turned him into a modern soldier who appreciated and employed the rapid advances in weaponry, including the breech loading carbine and repeating rifle with tremendous effect.

Despite moving to Illinois Buford’s family still held Southern sympathies; his father was a Democrat who had opposed Abraham Lincoln. Buford himself was a political moderate and though he had some sympathy for slave owners:

“he despised lawlessness in any form – especially that directed against federal institutions, which he saw as the bulwark of democracy…..He especially abhorred the outspoken belief of some pro-slavery men that the federal government was their sworn enemy.” [57]

After the election of Abraham Lincoln, the officers of Buford’s regiment split on slavery. His regimental commander, Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, a Virginian and the father-in-law of J.E.B. Stuart announced that he would remain loyal to the Union, others like Beverly Robertson who would command a brigade of cavalry during the Gettysburg campaign resigned their commissions.

For many officers, both those who remained loyal to the Union and those who joined the Confederate cause the decision was often difficult, and many anguished over their decisions as they weighed their allegiance to the Union against their loyalty to home and family. Buford was not one of them.

Since Buford’s family had longstanding ties to Kentucky, the pro-secession governor of Kentucky, Beriah Magoffin offered Buford a commission in that states’ militia. At the time Kentucky was still an “undeclared border slave state” and Buford loyal to his oath refused the governor’s offer. He wrote a brief letter to Magoffin and told his comrades that “I sent him word that I was a Captain in the United States Army and I intend to remain one.” [58] Around the same time the new provisional government of the Confederacy “offered Buford a general officer’s commission, which reached him by mail at Fort Crittenden.” [59] According to Buford’s biographer Edward Longacre “a well-known anecdote has him wadding up the letter while angrily announcing that whatever future had in store he would “live and die under the flag of the Union.” [60]

However Buford’s family’s southern ties, and lack of political support from the few remaining loyal Kentucky legislators initially kept him from field command. Instead he received a promotion to Colonel and an assignment to the Inspector General’s Office, although it was not the field assignment that he desired it was of critical importance to the army in those early days of the war as the Union gathered its strength for the war. Buford was assigned to mustering in, and training the new regiments being organized for war. Traveling about the country he evaluated each unit in regard to “unit dress, deportment and discipline, the quality and quantity of weapons, ammunition, equipment, quarters, animals and transportation; the general health of the unit and medical facilities available to it; and the training progress of officers and men.” [61] Buford was a hard and devastatingly honest trainer and evaluator of the new regiments. He was especially so in dealing with commanding officers as well as field and company officers. Additionally he was a stickler regarding supply officers, those he found to be incompetent or less than honest were cashiered.

Buford performed these duties well but desired command. Eventually he got the chance when the politically well-connected but ill-fated Major General John Pope who “could unreservedly vouch for his loyalty wrangled for him command of a brigade of cavalry.” [62] After Pope’s disastrous defeat at Second Bull Run in August 1862 Buford was wounded in the desperate fighting at Second Manassas and returned to staff duties until January 1863 when he was again given a brigade. However, unlike many of the officers who served under Pope, Buford’s reputation as a leader of cavalry and field commander was increased during that campaign.

Buford was given the titular title of “Chief of Cavalry of the Army of the Potomac” by George McClellan, a title which sounded impressive but involved no command during the Antietam campaign. Following that frustrating task he continued in the same position under his old West Point friend Ambrose Burnside during the Fredericksburg campaign. Buford lost confidence in his old friend and was likely “shocked by his friend’s deadly ineptitude, his dogged insistence on turning defeat into nightmare.” [63]

When Burnside was relieved and Fighting Joe Hooker appointed to command the army, Buford’s star began to rise. While he was passed over by Hooker for command of the newly organized First Cavalry division in favor of Alfred Pleasanton who was eleven days his senior, he received command of the elite Reserve Brigade composed of mostly Regular Army cavalry regiments. When Major General George Stoneman was relieved of command following the Chancellorsville campaign, Pleasanton was again promoted over Buford.

In later years Hooker recognized that Buford “would have been a better man for the position of chief” [64] but in retrospect Buford’s pass over was good fortune for the Army of the Potomac on June 30th and July 1st 1863. Despite being passed over for the Cavalry Corps command, Buford, a consummate professional never faltered or became bitter. Despite the Pleasanton’s interference and “lax intelligence-gathering” [65] During the Gettysburg campaign he led his brigade well at Brandy Station as it battled J.E.B. Stuart’s troopers, after which he was recommended for promotion and given command of the First Cavalry division of the Cavalry Corps. [66]

Following Brandy Station Buford led his troopers aggressively as they battled Stuart’s troopers along the Blue Ridge at the battles of Aldie, Philmont, Middleburg and Upperville. It was at Upperville while fighting a hard action Confederate Brigadier general “Grumble” Jones’s brigade that Buford’s troopers provided Hooker with the first visual evidence that Lee’s infantry was moving north into Maryland and Pennsylvania.

When Hooker was relieved on the night of June 27th and 28th George Meade gave Buford the chance at semi-independent command without Pleasanton looking over his shoulder. Meade appreciated Pleasanton’s administrative and organizational expertise and took him out of direct field command. Meade had his Cavalry Corps commander “pitch his tent next to his own on almost every leg of the trip to Pennsylvania and rarely let him out of sight or earshot.” [67]

The result was that when ordered to screen the army as it moved into Pennsylvania Buford was confident of his troopers and their ability and he and his men performed their duties admirably. On June 29th Buford’s men skirmished with two of Harry Heth’s regiments near the town of Fairfield, which Buford promptly reported to Meade and John Reynolds after ascertaining their size and composition. The following morning Buford and his troopers arrived in Gettysburg and were greeted by the townspeople who “thronged the streets, waving, shouting, and singing patriotic songs as Buford’s advance pushed through.” [68] Marching through the town they took up positions on the ridges west of the town. As they moved west the advance elements of Buford’s brigade discovered the presence of Johnston Pettigrew’s North Carolina brigade which promptly withdrew when it discovered that it was facing regular Federal cavalry.

Despite the welcome of the townsfolk, Buford’s troopers were tired from the weeks of incessant marching and combat. Their horses needed fodder, which was barely adequate, and most needed to be reshod, but because Early’s division had “seized nearly every shoe and nail”…”he had neither materials nor facilities for reshoeing them.” [69] Despite their fatigue Buford’s men had one distinctive advantage over the Confederates that they would face, this was in their weaponry. With few exceptions the Union cavalry at Gettysburg went into battle with “the finest equipment and arms obtainable. The troopers in almost every regiment carried breech-loading carbines (usually Sharp’s singe shot) hitched to their belts; they also carried revolvers (usually Colt army) and cavalry sabers.” [70] Though outnumbered their weapons gave them an edge in maintaining a heavy fire against the Confederate infantry which was armed with a variety of muzzle-loaded rifled muskets.

Based on all the intelligence available to him, that of George Sharpe’s Bureau of Military Information and that of his own scouts Buford “gathered that the whole of Hill’s Corps was “massed back of Cashtown” to the west, but there was also clear indication that Ewell’s Corps was “coming over the mountains from Carlisle,” to the north.” [71] Buford sent that news to Reynolds and to Meade by way of Pleasanton by mounted courier the evening of June 30th. The report caused Reynolds to realize the importance of Gettysburg and he immediately sent orders for Buford “to hold onto it to the last.” If Buford could buy enough time, he might get his infantry into line “before the enemy could seize the point.” [72]

Since Buford suspected that Ewell’s troops might also arrive he posted forces a few miles to the north of Gettysburg to provide warning and to delay them if needed, however since Buford determined that “Hill represented the more immediate threat, Buford resolved to concentrate most of his strength west of the town along MacPherson’s Ridge.” [73]

Brigadier General John Buford U.S.A.

On the night of June 30th Buford prepared for battle. Unlike Hill and Heth he understood exactly what he was facing. He met with “reliable men” most likely from the Bureau of Military Intelligence operated by David McConaughy as to the composition of Lee’s forces. [74] Buford knew his business; he took the time to reconnoiter the ridges west of Gettysburg and posted videttes as far was as Marsh Creek. He deployed one brigade under Colonel Thomas Devin to the north and west of the town, Colonel William Gamble’s brigade was deployed to the west, its main line being on McPherson’s Ridge.

As he deployed his forces Buford formulated his plan. Riding with his brigade commanders and staff “Buford, puffing away on his pipe, peering through field glass, studied the road network and lay of the land. He calculated distance to physical landmarks and tried to determine how long it would take those Confederates massing behind South Mountain to come within carbine range.” [75] Buford’s composure and confidence inspired his troopers as well as local civilians who observed him as he surveyed the ground on which the greatest battle ever waged on American soil would be fought.

Considering that he had fewer than three-thousand troopers available at Gettysburg because the Reserve Brigade was still further south guarding the army’s trains, and that he was facing a foe many times larger, it was a bold plan. Buford seems to have convinced himself that “he could pull off something never achieved in this war: a defense in depth by dismounted cavalry against a force of foot soldiers with full artillery support.” [76] As such the crafty Buford planned “a defense in depth, fighting his men dismounted, using the series of ridgelines west of Gettysburg to hamper and delay the Rebel infantry he was certain would come “booming along” the Chambersburg Pike in the morning.” [77]

Noting that the ground was favorable to defense and giving battle Buford sent messages to Reynolds as to the situation. He warned Reynolds that “A.P. Hill’s corps is massed just back of Cashtown, about 9 miles from this place.” He also noted the location of Confederate pickets “only four miles west of Gettysburg.” [78] Devin’s troops also identified elements of Ewell’s corps north of the town. Buford had accurately informed his superiors of what was before him, information that they needed for the day of battle.

Buford set up his headquarters at the Eagle Hotel in Gettysburg where he spent the night and according to his signals officer was “anxious, more so than I ever saw him” [79] Buford discussed the tactical situation with Colonel Devin, commanding the brigade on Herr’s and McPherson’s Ridge. Devin did not yet believe that the Confederates would move on Gettysburg in the morning. Devin thought if there were any threats that “he could handle anything that could come up in the next 24 hours.” [80] Buford rejected Devin’s argument and told him bluntly “No you won’t…. They will attack you in the morning and they will come booming – skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own.” [81]

In preparation for the Confederate advance Buford deployed about seven hundred of his men in videttes, or pickets several miles in advance of the main force of his division. These videttes stretched from the Blackhorse Tavern south and west of Gettysburg, across the Mummasburg and Carlisle Roads, ending east of town on the York Pike. The center of this line was along the Chambersburg or Cashtown Pike along Marsh Creek about five miles west of Gettysburg. These videttes were critical in ascertaining the direction and composition of any advancing Confederate forces.

Reynolds immediately saw the importance of the position elected to fight. He “ordered Buford to hold onto it to the last” believing that if Buford could “buy enough time, he might get his infantry into line “before the enemy should seize the point.” [82] Buford knew that against the odds he would face that he would only be able to hold for a few hours at best and since by “refusing to flee from Lee’s path, by committing himself to fight in an advanced position however favorable, he risked not only his division’s annihilation but the disarranging of Meade’s plans” [83] to fight a defensive battle along the Pipe Creek line. Buford and Reynold’s bold decisions on that last night of June 1863 committed the Army of the Potomac to battle Lee’s hearty veterans at Gettysburg.

Buford’s Delaying Action July 1st

For Buford’s troopers the night and morning of June 30th and July 1st 1863 was spent in grim anticipation that they would meet a good portion of Lee’s army in battle. “It was a jumpy night, and the lowering clouds “poured down a drenching rain” [84] even as Buford’s advanced videttes observed the camp fires of the advanced Confederate outposts left by Pettigrew on the 30th of June.

As the over-confident and lackadaisical Confederates advanced in the pre-dawn early morning mist they had a hard time determining what lay ahead of them and they “halted as they got to the swampy land fringing Marsh Creek, beyond which the ground angled up into a single swell to a ridge line.” [85] Pegram’s artillerists surveyed the ground to their front and noted mounted troops, but the limited visibility made it impossible to identify them, some even thought that they might belong to Longstreet’s corps, however Pegram knowing Longstreet’s corps was well the west, stopped his advance and unlimbered is guns. This caused the commander of Archer’s lead brigade, Colonel Birkett D. Fry of the 13th Alabama to ask Pegram what was going on and why he had stopped his advance. Upon seeing the artillery readying for action Fry “rode back to the color bearer and ordered him to uncase the colors.” [86] This was the first indication that the enemy was near and Fry quickly ordered his regiment to establish a skirmish line.

With the sun coming up the Union troops saw the now uncased colors of the Confederate battle flags to their front. Lieutenant Marcellus Jones of the 8th Illinois, commanding one of the detachments along Marsh Creek, expecting such rode to one of his advanced posts. He took a carbine from one of his sergeants and said “Hold on George, give me the honor of opening this ball” and at about 7:30 a.m. Jones fired the first shot of the battle of Gettysburg. [87]

Heth had wanted to advance in column as long as possible “but the Yankee cavalry’s stiff resistance had ended that hope.” [88] Heth rode forward and ordered Archer and Davis’s troops to advance skirmishers with the support of Pegram’s artillery. This slowed the Confederate advance considerable and Heth wrote in his after action report that “it became evident that there were infantry, cavalry and artillery in and around the town.” [89] At this point, Heth should have stopped and sought guidance on what to do next, however, instead of “feeling out the enemy” as directed by Hill, Heth “ordered Archer and Davis “to move forward and occupy the town.” [90] A chaplain in Brockenbrough’s brigade reported that one of Heth’s aide’s came up and reported “General Heth is ordered to move on Gettysburg, and fight or not as he wishes.” The chaplain heard one of the officers near him say “We must fight them; no division general will turn back with such orders.” [91]

Heth obviously expected small detachments of cavalry to give way at the sight of massed infantry, but Buford and his men had other plans. Instead of withdrawing the small cavalry detachments dismounted and used trees, bushes and fence lines for cover and poured forth a rapid fire with their Sharps carbines. This forced Heth’s skirmishers to advance slowly and deliberately, and forced the main body of his advanced brigades to deploy into battle formation supported by Pegram’s artillery.

About 8:00 A.M. Colonel Gamble who commanded the Buford’s First Brigade to which the videttes belonged “received a report that a strong enemy force was driving in his pickets.” [92] Gamble promptly reported this to Buford who in turn directed Gamble to deploy his “1,600 troopers to form a battle line on Herr’s Ridge a mile west of the seminary” [93] from which Buford was now directing his division. Likewise Buford ordered Devin’s Second Brigade to take up positions north of the Pike. He likewise order Lieutenant John Calef who commanded Battery “A” Second United States Horse Artillery to deploy his six three inch rifles along the ridge. However, instead of deploying them in an orthodox manner Buford ordered Calef to “spread his pieces wide apart to deceive the enemy into thinking his battery was actually two artillery units.” [94]

Everything that Buford did served to further confuse Heth, who now because of the heavy volume of fire his troops were receiving and his inability to see the horses of the dismounted cavalry believed that he was facing Federal infantry and artillery for Buford’s troopers “surely acted like infantry.” [95] Captain Amasa Dana of Company E. of the 8th Illinois “ordered his men to “throw up their carbine sights and [we] gave the enemy the benefit of long range practice [;] the firing was rapids from our carbines, and at the distance induced the enemy to the belief of four times our number actually present….” [96]

Instead of driving the cavalry out by force of numbers the Confederates had to advance deliberately to drive out the Union troopers, forcing Archer’s men to “undertake the time-consuming task of fixing the enemy in place, and then working parties around its flanks or any other chinks they could find.” [97] As they did this the veteran Union troopers withdrew and formed again, each time forcing the Confederates to slow their advance on Gettysburg.

Buford’s defense in depth was unlike anything that the Confederates had experienced at the hands of the Army of the Potomac. At each position Gable’s troopers continued to hold and his “carbineers continued to blast away as fast as they could reload, Calef’s shells thundering over their heads to burst in the fields beyond.” [98] That defense gave Buford an extra two hours and at 9:00 he directed his brigades to fall back to the next line of defense that of McPherson’s Ridge, where Buford’s troopers established another line.

Seeing the enemy before him Harry Heth committed yet another error. He was not going to let the Federal force stop him from reaching Gettysburg. On Herr’s Ridge he made a fateful decision. He spend over half an hour, from 9:00 until just past 9:30 deploying Archer’s Brigade in line of battle “and extending its left flank with the next brigade in line, that of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis.” [99] Once that was accomplished Heth ordered Archer and Davis’s brigades forward toward Buford’s troops. It was a deadly mistake for Heth had no idea that the advance elements of John Reynold’s First Corps were rapidly moving to support Buford and that his troops were about to experience a fight like which they had never seen or expected. Despite this the Confederates pushed on and were threatening to force Buford’s troops from McPherson’s Ridge and “victory seemed to be at hand, but as the 13th Alabama climbed from the Willoughby Run ravine into a field south of McPherson Wood’s its men saw a Union line of battle a hundred yards to the front.” [100] John Reynold’s First Corps led by the famous Iron Brigade of Abner Doubleday’s First Division had arrived on the field.

The fight that Harry Heth and A.P. Hill had been directed not to precipitate was now on. Heth’s inexperience was more than matched by the cunning and brilliant Buford, whose troopers had fought a masterful delaying action, one which prefigured the later use of cavalry and eventually armored cavalry and motorized reconnaissance in later wars. Buford’s masterful defense along Marsh Creek, and Herr’s and McPherson’s Ridge enabled Reynolds’s infantry to come up before the Confederates could seize the key high ground to the west of Gettysburg.

Notes

[1] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.78

[2] Robertson, James I. Jr. General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior Random House, New York 1987 p.206

[3] Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg: A.P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell in a Difficult Debut in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.44

[4] Ibid Robertson General A.P. Hill p.206

[5] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p. 137

[6] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.44

[7] Ibid Robertson General A.P. Hill p.206

[8] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.92

[9] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command A Touchstone Book, Simon and Shuster New York 1968 p.264

[10] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p.51

[11] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.79

[12] Pryor, Elizabeth Brown. Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters Penguin Books, New York and London 2007 p.352

[13] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.264

[14] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p.230

[15] Wert, Jeffry D. A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2011 p.234

[16] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.90

[17] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.234

[18] Ibid Robertson General A.P. Hill pp.206-207

[19] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.91

[20] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.147

[21] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.153

[22] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.32

[23] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.32

[24] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.153

[25] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.32

[26] Alexander, Edward Porter Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative 1907 republished 2013 by Pickle Partners Publishing, Amazon Kindle Edition location 7342 of 12968

[27] Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation pp.91-92

[28] Ibid Robertson General A.P. Hill p.206

[29] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.92

[30] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.153

[31] Ibid. Gallagher Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.44

[32] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.153

[33] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.274

[34] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.274

[35] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 161

[36] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.52

[37] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.153

[38] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.131

[39] Ibid Robertson General A.P. Hill p.207

[40] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.93

[41] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.135

[42] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.134

[43] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.264

[44] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 162

[45] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.134

[46] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 162

[47] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.93

[48] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.156

[49] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.93

[50] Pfanz. Gettysburg: The First Day p.53

[51] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.158

[52] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.264

[53] Longacre, Edward G. John Buford: A Military Biography Da Capo Press, Perseus Book Group, Cambridge MA p.17

[54] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[55] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.36

[56] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.36

[57] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.54

[58] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[59] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.70

[60] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.70

[61] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.78

[62] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.121

[63] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.122

[64] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.44

[65] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.173

[66] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.64

[67] Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June-14 July 1863 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 1986 p.168

[68] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.181

[69] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.133

[70] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.258

[71] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.142

[72] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.122-123

[73] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, pp.142-143

[74] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.141

[75] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.184

[76] Ibid. Longacre The Cavalry at Gettysburg p.185

[77] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 157

[78] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.122

[79] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 157

[80] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.266

[81] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.123

[82] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.122-123

[83] Ibid. Longacre The Cavalry at Gettysburg p.185

[84] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.132

[85] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.158

[86] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, pp.158-159

[87] Pfanz. Gettysburg: The First Day p.53

[88] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 163

[89] Luvaas, Jay and Nelson Harold W editors. The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg South Mountain Press, Carlisle PA 1986 p.7

[90] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 165

[91] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.163

[92] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.266

[93] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p.266

[94] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.191

[95] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p. 164

[96] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.162

[97] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.162

[98] Ibid. Longacre The Cavalry at Gettysburg p.187

[99] Ibid. Longacre John Buford p.191

[100] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: The First Day p.68