“Danger is part of the friction of war. Without an accurate conception of danger we cannot understand war. That is why I have dealt with it here.” Carl Von Clausewitz [1]

When commanders send their troops into battle to execute the plans of their staff, they cannot forget that as Clausewitz noted that War is the province of danger and that:

“In the dreadful presence of suffering and danger, emotion can easily overwhelm intellectual conviction, and in the psychological fog it is so hard to form clear and complete insights that changes in view become more understandable and excusable….No degree of calm can provide enough protection: new impressions are too powerful, too vivid, and always assault the emotions as well as the intellect.” [2]

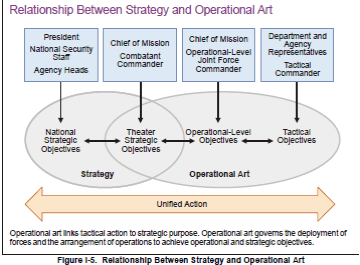

To re-engage our understanding of this issue is important, especially in the application of Mission Command where as General Martin Dempsey noted that “Understanding equips decision makers at all levels with the insight and foresight to make effective decisions, to manage the associated risks, and to consider second and subsequent order effects.” [3] The current and recent wars fought by the United States and its NATO and coalition allies have shielded many military professionals from this aspect of war, but it is still present and we should not ignore it. As noted in the 2006 edition of the Armed Forces Officer:

“The same technology that yields unparalleled success on the battlefield can also detach the warrior from the traditional ethos of the profession by insulating him or her from many of the human realities of war.” [4]

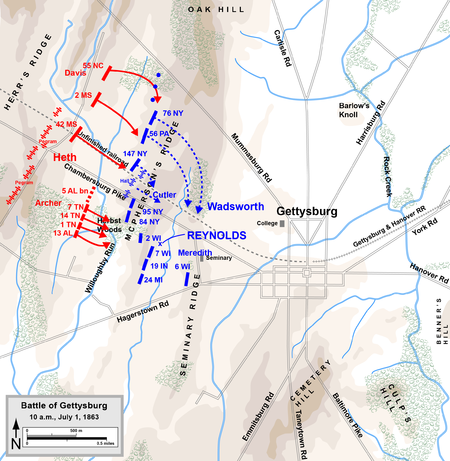

“The nature of the warrior leader is driven by the requirements of combat” [5]and courage, both “courage in the face of the danger, and the courage to accept responsibility” [6] are of paramount importance. In an era where the numbers of soldiers that actually experience combat or served in true combat conditions where the element of danger is ever present is shrinking, we can at least gain part of that understanding through the study of history, campaigns and battles and by actually walking the battlefields, and considering the effects of terrain, weather, exhaustion and the imagining danger faced in confronting an enemy on the field of battle. As such the Battle of Gettysburg and the climactic event of Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd is a good place to reimagine the element of danger.

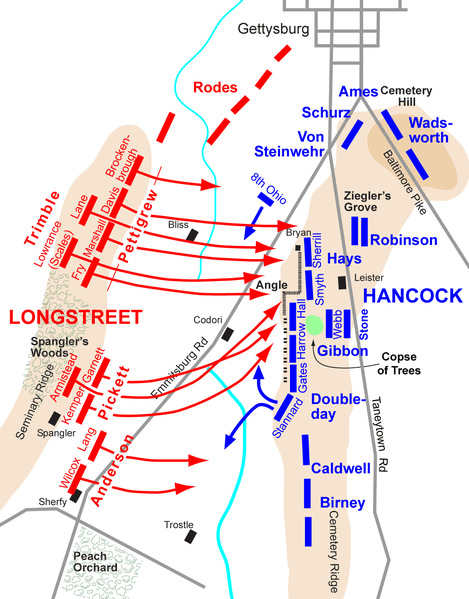

Porter Alexander’s artillery had begun it’s bombardment at 1:07 p.m. and as it did and the Union artillery commenced a deliberate counter-fire the Confederate infantry behind Seminary Ridge began to take a beating. Unlike the Confederate barrage which had mainly sailed over the Union troops on Cemetery Ridge causing few causalities, “a large proportion” of the Union “long shots landed squarely in the ranks of the gray soldiers drawn up to await the order to advance.” [7] Estimates vary but the waiting Confederates lost between 300-500 killed and wounded, the most affected was Kemper’s brigade of Pickett’s division which lost about 250 men, or 15% of its strength. [8] Other units lost significant numbers, with those inflicted on Pettigrew’s brigades further depleting their already sparse numbers.

Composed of Pickett’s fresh division from First Corps, Heth’s battered division now under Pettigrew which had already taken close to 40% casualties. Of the two brigades of Pender’s division now commanded by Trimble, Lane’s which was fresh but Scales brigade, now under command of Colonel William Lowrence had suffered greatly on July 1st; its “casualty rate was 63% and it had lost its commander and no fewer than fifty-five field and company grade officers.” [9] And now, these battered the units began to take casualties from well directed Federal fire. George Stewart wrote: “In most armies, such a battered unit would have been sent to the rear for reorganization, but here it was being selected for a climactic attack!” [10]

“The Confederate losses mounted at an alarming rate. The psychological impact of artillery casualties was great, for the big guns not only killed but mangled bodies, tore them apart, or disintegrated them.” [11] A survivor wrote his wife days later: “If the crash of worlds and all things combustible had been coming in collision with each other, it could not have surpassed it seemingly. To me it was like the “Magazine of Vengeance” blown up.” [12] A soldier of Kemper’s brigade recalled “The atmosphere was rent and broken by the rust and crash of projectiles…The sun, but a few minutes before so brilliant, was now darkened. Through this smoky darkness came the missiles of death…the scene beggars description…Many a fellow thought his time had come…Great big, stout hearted men prayed, loudly too….” [13] Colonel Joseph Mayo of the 3rd Virginia regiment was heavily hit, one of its survivors wrote “when the line rose up to charge…it appeared that as many were left dead and wounded as got up.” [14]

On the opposite ridge Union forces were experiencing the same kind of intense artillery fire. But these effects were minimized due to the prevalent overshooting of the Confederate artillery as well as the poor quality of ammunition. This resulted in few infantry casualties with the worst damage being taken by a few batteries of artillery at the angle. Soldiers behind the lines took the worst beating, but “the routing of these non-combatants was of no military significance,” [15] This did create some problems for the Federals as Meade was forced to abandon their headquarters and the Artillery Reserve was forced to relocate “a little over a half mile to the rear.” [16] The effects of this on operations were minimal as Brigadier General Robert Tyler commanding the Artillery Reserve “posted couriers at the abandoned position, should Hunt want to get in touch with him.” [17]

Despite the fusillade Meade maintained his humor and as some members of his staff tried to find cover on the far side of the little farmhouse quipped:

“Gentlemen, are you trying to find a safe place?…You remind me of the man who drove the oxen team which took ammunition for the heavy guns to the field at Palo Alto. Finding himself in range, he tipped up his cart and hid behind it. Just then General Taylor came along and shouted “You damned fool, don’t you know you are no safer there than anywhere else?” The driver responded, “I don’t suppose I am general, but it kind of feels so.” [18]

Despite the unparalleled bombardment, the likes which not had been seen on the American continent, the Confederate artillery had little actual effect on the charge. The Prussian observer travelling with Lee’s headquarters “dismissed the barrage as a “Pulververschwindung,”…a waste of powder. [19] The Federal infantry remained in place and ready to meet the assault, Hunt replaced his damaged batteries and even more importantly Lieutenant Colonel Freeman McGilvery’s massive battery was lying undetected where it could deliver devastating enfilade fire as were Rittenhouse’s batteries on Little Round Top and Osborne’s on Cemetery Hill. These guns, unaffected by the Confederate bombardment were poised to wreak destruction on the men of the three Confederate divisions.

Unlike the Federal Army which had its large pool of artillery battalions in the Artillery Reserve with which to replace batteries that had taken casualties or were running low on ammunition, and “soon the drivers of the caissons found that the heavy fire had exhausted their supply of shot and shell, and the had to go even farther to get it from the reserve train. As a result some of the guns remained mute and their gunners stood helpless during the cannonade and charge, for Alexander had no batteries in reserve to replace them.” [20] The reason for this was that the Confederates had reorganized their artillery before Chancellorsville with all batteries assigned directly to the three infantry corps leaving the army without a reserve, and because Brigadier General William Pendleton had relocated the artillery trains further to the rear without informing Alexander or Longstreet. He had also ordered the eight guns of the Richardson’s artillery away without notifying anyone, guns which Alexander was counting on to support the attack. At about 2:20 p.m. Alexander, knowing that he was running short of ammunition sent a note to Picket and Pettigrew advising them:

“General: If you are to advance at all, you must come at once or we will not be able to support you as we ought. But the enemy’s fire has not slackened and there are still 18 guns firing from the cemetery.” [21]

About twenty minutes later Alexander saw some of the guns along Cemetery Ridge begin to limber up and depart, and noticed a considerable drop off in Federal fire. Now confident that his guns had broken the Federal resistance, at 2:40 sent word to Pickett “For God’s sake come quick or my ammunition will not let me support you.” [22] However, what Alexander did not realize was that to conserve ammunition for the Confederate infantry charge Henry Hunt had ordered those batteries to withdraw and was replacing them with fresh batteries and had ordered an “immediate cessation and preparation for the assault to follow.” [23]

The message reached Pickett and Pickett immediately rode off to confer with Longstreet. Pickett gave the message to Longstreet who read it “and said nothing. Pickett said, “General, shall I advance!” Longstreet, knowing it had to be, but unwilling to give the word, turned his face away. Pickett saluted and said “I am going to move forward, sir” galloped off to his division and immediately put it in motion.” [24]

A few minutes later Longstreet rode to find Alexander. Meeting him at 2:45 and Alexander informed him of the shortage of ammunition, which upset him enough that he “seemed momentarily stunned” [25] by this news Longstreet told Alexander, “Stop Pickett immediately and replenish your ammunition.” [26] But Alexander now had to give Longstreet even worse news telling him “I explained that it would take too long, and the enemy would recover from the effect of our fire was then having, and too that we had, moreover, very little to replenish it with.” [27] Longstreet continued to ride with Alexander and again eyed the Federal positions on Cemetery Ridge with his binoculars and said “I don’t want to make this attack,” pausing between sentences as if thinking aloud. “I believe it will fail- I do not know how it can succeed- I would not make it even now, but Gen. Lee has ordered it and expects it.” [28] Alexander, who as a battalion commander now in charge of First Corps artillery was uncomfortable, he later wrote:

“I had the feeling that he was on the verge of stopping the charge, & that with even slight encouragement he would do it. But that very feeling kept me from saying a word, or either assent I would not willingly take any responsibility in so grave a matter & I had almost a morbid fear of causing any loss of time. So I stood by, & looked on, in silence almost embarrassing.” [29]

While Longstreet was still speaking Pickett’s division swept out of the woods to begin the assault, Alexander knew that “the battle was lost if we stopped. Ammunition was too low to try anything else, for we had been fighting for three days. There was a chance, and it was not my part to interfere.” [30]

Despite this Pickett and many of his soldiers were confident of success, and “no officer reflected the men’s confidence better than George Pickett. There was no fatalism in him. Believing that his hour of destiny had come and expecting to take fortune at its flood, he rode down the slop like a knight in a tournament.” [31] Pickett was “an unforgettable man at first sight” [32] Pickett was exceptionally undistinguished in the West Point class of 1846, graduating last in the class, but “fought valiantly in a number of battles” [33] during the Mexican War alongside James Longstreet. Like many he officers he resigned his commission in 1861 and received a colonelcy in the new Confederate army. During the Seven Days battles he commanded a brigade, which was now commanded by Richard Garnett and was wounded at Gaines Mill. Promoted to Major General in the summer of 1862 Pickett received command of the division formerly commanded by David R. Jones. The division was sent to peripheral areas and took no part in the battles of late 1862 or Chancellorsville. Reduced from its five brigade strength due to the insistence of Jefferson Davis to leave forces to protect Richmond the division was built around the brigades of James Kemper, Lewis Armistead and Richard Garnett.

When Pickett’s division as well as those of Pettigrew and Trimble swept out of the wood to begin the attack the last chance to stop it ended. As Pickett’s brigades moved out he encouraged them shouting “Remember Old Virginia!” or to Garnett’s men “Up, men, and to your posts! Don’t forget today that you are from Old Virginia!” [34] But when Garnett asked if there were any final instructions Pickett was told “I advise you to make the best kind of time in crossing the valley; it’s a hell of an ugly looking place over yonder.” [35] Armistead called out to his soldiers, “Men, remember who you are fighting for! Your homes, your firesides, and your sweethearts! Follow Me!” [36]Armistead’s example had a major impact on his brigade, men were inspired, as one later wrote “They saw his determination, and they were resolved to follow their heroic leader until the enemy’s bullets stopped them.” [37] about 500 yards to Pickett’s left Pettigrew exhorted his men “for the honor of the good old North State, forward.” [38]

Pickett’s division “showed the full length of its long gray ranks and shining bayonets, as grand as a sight as ever a man looked on.” [39] The sight was impressive on both sides of the line, a Confederate Captain recalling the “glittering forest of bayonets” the two half mile wide formations bearing down “in superb alignment.” [40] even impressing the Federals. Colonel Philippe Regis de Trobriand, a veteran of many battles in Europe and the United States recalled “it was a splendid sight,” [41] and another recalled that the Confederate line ‘gave their line an appearance of being irresistible.” [42]

But the Federals were confident. Having withstood the Confederates for two days and having survived the artillery bombardment the Union men eagerly awaited the advancing Confederates. Directly facing the Confederate advance in the center of the Union line was the division of John Gibbon. The cry went out “Here they come! Here they come! Here comes the infantry!” [43] To the left of Gibbon Alexander Hays called to his men “Now boys look out…now you will see some fun!” [44]

The Confederates faced difficulties as they advanced, and not just from the Union artillery which now was already taking a terrible toll on the advancing Confederates. Stuck by the massed enfilade fire coming from Cemetery Hill and Little Round Top continued their steady grim advance. Carl Schurz from his vantage point on Cemetery Hill recalled:

“Through our field-glasses we could distinctly see the gaps torn in their ranks, the grass dotted with dark spots- their dead and wounded….But the brave rebels promptly filled the gaps from behind or by closing up on their colors, and unasked and unhesitatingly they continued with their onward march.” [45]

Pettigrew’s division was met by fire which enveloped them obliquely from Osborne’s 39 guns on Cemetery Hill. On the left flank a small regiment, the 8th Ohio lay in wait. Seeing an opportunity the commander Lieutenant Colonel Franklin Sawyer deployed his 160 men in a single line, took aim at Brockenbrough’s Virginia brigade some two hundred yards ahead of the Emmitsburg Road, and opened a devastating fire. “Above the boiling clouds the Union men could see a ghastly debris of guns, knapsacks, blanket rolls, severed human heads, and arms and legs and parts of bodies tossed into the air by the impact of the shot.” [46] So sudden and unexpected was this that the Confederates panicked and “fled in confusion…” to the rear where they created more chaos in Trimble’s advancing lines as one observed they “Came tearing through our ranks, which caused many men to break.” [47] The effect on Confederate morale was very important, for “the Army of Northern Virginia was not used to seeing a brigade, even a small one, go streaming off to the rear, with all its flags….Even Pickett’s men sensed that something disastrous had happened on the left….” [48]

In one fell swoop Pettigrew was minus four regiments. Brockenbrough was singularly ineffective in leading his men, he “was a nonentity who did not know how to control his recalcitrant rank and file; nor did he have the presence to impress his subordinate officers and encourage them to do his bidding.” [49] The disaster that had overtaken Brockenbrough’s brigade now threated “another important component of Lee’s plan-the protection so necessary for the left flank of the advancing line had collapsed.

Pettigrew’s division continued its advance after Brockenbrough’s brigade collapsed, but the Confederate left was already beginning to crumble. “Sawyer changed front, putting his men behind a fence, and the regiment began firing into the Confederate flank.” [50] with Davis’s brigade now taking the brunt of the storm of artillery shells from Osborne’s guns. This brigade had suffered terribly at the railroad cut on July 1st, especially in terms of field and company grade officers was virtually leaderless, and “the inexperienced Joe Davis was helpless to control them.” [51] To escape the devastating fire Davis ordered his brigade to advance at the double quick which brought them across the Emmitsburg Road ahead of the rest of the division, where they were confronted by enfilade canister fire from Woodruff’s battery to its left, as well as several regiments of Federal infantry and from the 12th New Jersey directly in their front. A New Jersey soldier recalled “We opened on them and they fell like grain before the reaper, which nearly annihilated them.” [52] Davis noted that the enemy’s fire “commanded our front and left with fatal effect.” [53] Davis saw that further continuing was hopeless and ordered his decimated brigade “to retire to the position originally held.” [54]

Pettigrew’s remain two brigades continued grimly on to the Emmitsburg Road, now completely devoid of support on their left flank. Under converging fire from Hay’s Federal troops the remaining troops of Pettigrew’s command were slaughtered. Hay’s recalled “As soon as the enemy got within range we poured into them and the cannon opened with grape and canister [, and] we mowed them down in heaps.” [55] The combination of shot, shell, canister and massed musket fire “simply erased the North Carolinian’s ranks.” [56] Pettigrew was wounded, Colonel Charles Marshall killed 50 yards from the stone wall and “only remnants of companies and regiments remained unscathed.” [57] Soon the assault of Pettigrew’s division was broken:

“Suddenly Pettigrew’s men passed the limit of human endurance and the lines broke apart and the hillside covered with men running for cover, and the Federal gunners burned the ground with shell and canister. On the field, among the dead and wounded, prostrate men could be seen holding up handkerchiefs in sign of surrender.” [58]

Trimble’s two brigades fared no better. Scales brigade, now under the command of Colonel W. Lee Lowrence “never crossed the Emmitsburg Road but instead took position along it to fire at the enemy on the hill. The soldiers from North Carolina who two days before had marched without flinching into the maw of Wainwright’s cannon on Seminary Ridge could not repeat the performance.” [59] Trimble was severely wounded in the leg and sent a message to Lane to take command of the division. The order written in the third person added a compliment to his troops: “He also directs me to say that if the troops he had the honor to command today for the first time couldn’t take that position, all hell can’t take it.” [60] Lane attempted to rally the troops for one last charge when one of his regimental commanders exploded telling him “My God, General, do you intend rushing your men into such a place unsupported, when the troops on the right are falling back?” [61] Lane looked at the broken remains of Pettigrew’s division retiring from the field and ordered a retreat. Seeing the broken remnants of the command retreating, an aide asked Trimble if the troops should be rallied. Trimble nearly faint from loss of blood replied: “No Charley the best these brave fellows can do is to get out of this,” so “let them get out of this, it’s all over.” [62] The charge was over on the Confederate left.

The concentrated Federal fire was just as effective and deadly on the Confederate right. Kemper’s brigade, on the right of Pickett’s advance was mauled by the artillery of Rittenhouse on Little Round Top, which “tracked their victims with cruel precision of marksmen in a monstrous shooting gallery” and the overs “landed their shots on Garnett’s ranks “with fearful effect.” [63]

As the Confederates advanced Pickett was forced to attempt to shift his division to the left to cover the gap between his and Pettigrew’s division. The move involved a forty-five degree oblique and the fences, which had been discounted by Lee as an obstacle which along the Emmitsburg Road “virtually stopped all forward movement as men climbed over them or crowed through the few openings.” [64] Pickett’s division’s oblique movements to join with Pettigrew’s had presented the flank of his division to McGilvery’s massed battery. The movement itself had been masterful, the execution of it under heavy fire impressive; however it meant the slaughter of his men who were without support on their right flank.

As Pickett’s division advanced into the Plum Run Valley they were met by the artillery of Freeman McGilvery, who wrote that the “execution of the fire must have been terrible, as it was over a level plain, and the effect was plain to be seen. In a few minutes, instead of a well-ordered line of battle, there were broken and confused masses, and fugitives fleeing in every direction.” [65]

Kemper’s brigade which had the furthest to go and the most complicated maneuvering to do under the massed artillery fire suffered more damage. The swale created by Plum Run was a “natural bowling alley for the projectiles fired by Rittenhouse and McGilvery.” [66] was now flanked by Federal infantry as it passed the Condori farm. The Federal troops were those of the Vermont brigade commanded by Brigadier General George Stannard. These troops were nine month volunteers recruited in the fall of 1862 and due to muster our in a few days. They were new to combat, but one of the largest brigades in the army and 13th Vermont “had performed with veteran like precision the day before” [67] leading Hancock to use them to assault the Confederate right. The Vermonters were positioned to pour fire into the Confederate flank, adding to the carnage created by the artillery, and the 13th and 16th Vermont “pivoted ninety degrees to the right and fired a succession of volleys at pistol range on the right of Pickett’s flank.” [68]

Kemper had not expected this, assuming that the Brigades of Wilcox and Perry would be providing support on the flank. As he asked a wounded officer of Garnett’s brigade if his wound was serious, the officer replied that he soon expected to be a prisoner and asked Kemper “Don’t you see those flanking columns the enemy are throwing on our right to sweep the field?” [69] Kemper was stunned but ordered his troops to rush federal guns, but “they were torn to pieces first by the artillery and then by the successive musketry of three and a half brigades of Yankee infantry.” [70] Kemper was fearfully wounded in the groin, no longer capable of command. His brigade was decimated and parts of two regiments had to refuse their line to protect the flank, and those that continued to advance had hardly any strength left with which to succeed, the Confederate left was no for all intents and purposes out of the fight.

Now that fight was left in the hands of Armistead and Garnett’s brigades, and at this moment in the battle, the survivors of those units approached the stone wall and the angle where they outnumbered the Federal defenders, one regiment of which, the 71st Pennsylvania had bolted to the rear.

The survivors of Garnett’s brigade, led by their courageous but injured commander, riding fully exposed to Federal fire on his horse crossed the Emmitsburg Road and pushed forward overwhelming the few Federals remaining at the wall. They reached the outer area of the angle “which had been abandoned by the 71st Pennsylvania” and some of his men “stood on the stones yelling triumphantly at their foes.” [71] Armistead, leap over the wall shouting to his men “Come on boys! Give them the cold steel”…and holding his saber high, still with the black hat balanced on its tip for a guidon, he stepped over the wall yelling as he did so: “Follow me!” [72]

However, their triumph was short lived; the 72nd Pennsylvania was rushed into the gap by the brigade commander Brigadier General Alexander Webb. The climax of the battle was now at hand and “the next few minutes would tell the story, and what that story would be would all depend on whether these blue-coated soldiers really meant it…. Right here there were more Confederates than Federals, and every man was firing in a wild, feverish haste, with smoke settling down thicker and thicker.” [73] The 69th Pennsylvania, an Irish regiment under Colonel Dennis O’Kane stood fast and their fire slaughtered many Confederates. Other Federal regiments poured into the fight, famous veteran regiments the 19th and 20th Massachusetts, the 7th Michigan and the remnants of the 1st Minnesota who had helped stop the final Confederate assault on July 2nd at such fearful cost.

Dick Garnett, still leading his troops “muffled in his dark overcoat, cheered his troops, waving a black hat with a silver cord” [74] when he was shot down, his frightened horse running alone off the battlefield, a symbol of the disaster which had befallen Pickett’s division. Armistead reached Cushing’s guns where he was hit by several bullets and collapsed mortally wounded. “Armistead had been the driving force behind the last effort, there was no one else on hand to take the initiative. Almost as quickly as it had come crashing in, the Rebel tide inside the outer angle ebbed back to the wall.” [75]

For a time the Confederate survivors engaged Webb’s men in a battle at the wall itself in a stubborn contest. A Federal regimental commander wrote “The opposing lines were standing as if rooted, dealing death into each other.” [76] The Federals launched a local counterattack and many Confederates elected to surrender rather than face the prospect of retiring across the battlefield that was still swept by Federal fire.

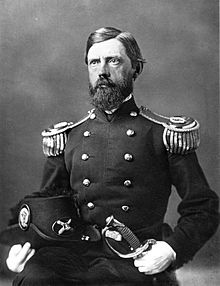

Webb had performed brilliantly in repulsing the final Confederate charge and “gained for himself an undying reputation. Faced with defeat, he accepted the challenge and held his men together through great personal exertion and a willingness to risk his life.” [77] For his efforts he was belatedly awarded the Medal of Honor.

Webb, like John Buford on July 1st, Strong Vincent, Freeman McGilvery and George Sears Greene on July 2nd, was instrumental in the Union victory. Hancock said of Webb “In every battle and on every important field there is one spot to which every army [officer] would wish to be assigned- the spot upon which centers the fortunes of the field. There was but one such spot at Gettysburg and it fell to the lot of Gen’l Webb to have it and to hold it and for holding it he must receive the credit due him.” [78]

The survivors of Pickett, Pettigrew and Trimble’s shattered divisions began to retreat, Lee did not yet understand that his great assault had been defeated, but Longstreet, who was in a position to observe the horror was. He was approached by Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle, a British observer from the Coldstream Guards. Fremantle did not realize that the attack had been repulsed, having just seen one of Longstreet’s regiments “advancing through the woods in good order” and unwisely bubbled “I would not have missed this for anything.” [79] Longstreet replied with a sarcastic laugh “The devil you wouldn’t” barked Longstreet. “I would have liked to have missed this very much; we’ve attacked and been repulsed. Look there.” [80] Fremantle looked out and “for the first time I then had a view of the open space between the two positions, and saw it covered with Confederates slowly and sulkily returning towards us in small broken parties, under a heavy fire of artillery.” [81] Henry Owen of the 18th Virginia wrote that the retreating men “without distinction of rank, officers and privates side by side, pushed, poured and rushed in a continuous stream, throwing away guns, blankets, and haversacks as they hurried on in confusion to the rear.” [82]

It was a vision of utter defeat. Pickett, who had seen his division destroyed and had been unable to get it additional support was distraught. An aide noted that Pickett was “greatly affected and to some extent unnerved” [83] by the defeat. “He found Longstreet and poured out his heart in “terrible agony”: “General, I am ruined; my division is gone- it is destroyed.” [84] Lee had come up by now and attempted to comfort Pickett grasping his hand and telling him: “General, your men have done all that they could do, the fault is entirely my own” and instructed him that he “should place his division in the rear of this hill, and be ready to repel the advance of the enemy should they follow up their advantage.” [85] The anguished Pickett replied, “General Lee, I have no division now. Armistead is down, Garnett is down and Kemper is mortally wounded.” [86]

Pickett’s charge was over, and with it the campaign that Lee had hoped would secure the independence of the Confederacy was effectively over, and the Battle of Gettysburg lost. “Lee’s plan was almost Burnside-like in its simplicity, and it produced a Fredericksburg with the roles reversed.” [87]

It was more than a military defeat, but a political one as well for with it went the slightest hope remaining of foreign intervention. As J.F.C. Fuller wrote “It began as a political move and it had ended in a political fiasco.” [88]

[1] Clausewitz, Carl von. On War Indexed edition, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976 p.114

[2] Ibid. Clausewitz On War p.108

[3] Dempsey, Martin Mission Command White Paper 3 April 2012 p.5 retrieved ( July 2014 from http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/concepts/white_papers/cjcs_wp_missioncommand.pdf

[4] ___________. The Armed forces OfficerU.S. Department of Defense Publication, Washington DC. January 2006 p.18

[5] Ibid. The Armed Forces Officer p.18

[6] Ibid. Clausewitz On War p.101

[7] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.548

[8] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 p.

[9] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.387

[10] Stewart, George R. Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3rd 1863Houghton Mifflin Company Boston 1959

[11] Hess, Earl J. Pickett’s Charge: The Last Attack at Gettysburg University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p.153

[12]Wert, Jeffery D. Gettysburg Day Three A Touchstone Book, New York 2001 p.181

[13] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.294

[14] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.179

[15] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge p.132

[16] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.496

[17] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.496

[18] Huntington, Tom Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of GettysburgStackpole Books, Mechanicsburg PA 2013 p.171

[19] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.163

[20] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.499

[21] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.459

[22] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.500

[23] Hunt, Henry The Third Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil Waredited by Bradford, Neil Meridian Press, New York 1989 p.374

[24] Alexander, Edwin Porter. The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil Waredited by Bradford, Neil Meridian Press, New York 1989 p.364

[25] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.501

[26] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[27] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[28] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage pp.474-475

[29] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[30] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p.261

[31] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.313

[32] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.109

[33] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.37

[34] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last InvasionVintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.408

[35] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.166

[36] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.167

[37] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.167

[38] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.483

[39] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[40] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.553

[41] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.407

[42] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.193

[43] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.193

[44] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.411

[45] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.422

[46] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.318

[47] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.423

[48] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg pp.193-194

[49] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.187

[50] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg p.193

[51] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.311

[52] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.494

[53] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.425

[54] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.494

[55] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.502

[56] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.216

[57] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.218

[58] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.318

[59] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.504

[60] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg pp.238-239

[61] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.504

[62] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.425

[63] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.555

[64] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.503

[65] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.217

[66] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.220

[67] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.515

[68] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.515

[69] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.502

[70] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.448

[71] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.505

[72] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.562

[73] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.319

[74] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.317

[75] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg p.508

[76] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.451

[77] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.528

[78] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.528

[79] Fremantle, Arthur Three Months in the Southern States, April- June 1863 William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London 1863 Amazon Kindle edition p.285

[80] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p.292

[81] Ibid. Fremantle Three Months in the Southern States p.287

[82] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.456

[83] bid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.326

[84] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.428

[85] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.428

[86] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.326

[87] Millet, Allan R. and Maslowski, Peter, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States The Free Press a Division of Macmillan Inc. New York, 1984 p.206

[88] Fuller, J.F.C. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1957 pp.200-201

Parallels between Tea Party Ideology and the Ante-Bellum South

I read a lot of political commentary and as a historian as well as a theologian I try to carefully examine mass movements such as the modern Tea Party Movement from a historical, theological and moral point of view. To do this as dispassionately as I can I look to history and attempt to find parallels to other movements and ideologies in the country concerned. For example if I am examining a movement in France, I look to French history for precedent, the same for any other country or region.

In regard to the Tea Party movement I have watched it since its inception in the fall of 2008 not long after I returned from Iraq. At the time I saw it as a protest against the massive failure of the American economy during the housing and stock market collapse involving the big banks and investment firms on Wall Street. I honestly did not believe that it would be a movement that has lasted as long as it has or would gain the amount of influence it has in the Republican Party. But then I saw it as a political and social protest and did not know enough about its leaders and their actual political ideology to make a serious connection to other political and social movements in U.S. History.

That being said, over the past six years I have had time to examine the movement, and while it is not monolithic there are within it many connections to previous American political movements, most of which would be classified as radically conservative. The movement is a curious combination of Libertarian leaning conservatives that preach a Libertarian form of unbridled Capitalism. There is also a religiously conservative element primarily composed of, but not limited to Evangelical Christians and conservative Roman Catholics focused more on social morality issues, particularly in regards to women’s issues, especially reproductive rights, abortion and homosexuality and LGTB rights and equality. There is also a collection of Second Amendment, or gun ownership proponents, anti-public education and pro-home school proponents, as well as others that advocate a number of conservative political beliefs, especially that of limited government. There is a highly volatile nativist element which has a nearly xenophobic world view, and a growing separatist militia movement that actively seeks confrontation with the Federal government.

However the movement does tend to mobilize over issues that they feel threaten their personal liberty, even if those issues have no actual effect on how they live their lives. This is particularly the case in terms of women’s issues and LGBT equality. This movement is particularly effective in taking political power at the local and state level and in many states have worked to roll back voting rights of minorities, particularly African Americans and uses the legislative and judicial process to advance their agenda, especially in terms of imposing a conservative Christian moral code on non-Christians or Christians that do not agree with them through the law, and this movement called Christian Dominionism is deeply ingrained in the personal philosophy and religious beliefs of many Tea Party leaders, both elected and unelected.

While many individual Tea Party members are moderate in their views, many are not and some advocate secession or overthrow of the present Federal government and are particularly united in their hatred of President Obama and any political official that will not completely embrace their agenda, thus Republican Tea Party members work to defeat moderate or conservative Republicans in primaries.

The thing is that none of this is new and that much of the current theology and philosophy in the Tea Party movement comes out of similar thought of the John Birch Society and well as the ante-Bellum South. While most Tea Party members would out rightly reject slavery, there often is a fair amount of racism displayed at their rallies, in their writings and in the declared goals of some groups. That is why that it is important to look to history, because the personal, religious, social and economic rights that many in the Tea Party embrace are directly concerned with limiting or rolling back the freedoms of minorities, women, immigrants and gays, thus the bridge to looking at the political, social, racial and religious issues that help to precipitate the American Civil War.

While the focus of this is on slavery, the same people who promoted the continued existence as well as expansion of slavery built a culture in which discrimination and the elevation of a political and social aristocracy was the goal. In addition to African Americans the leaders of the Southern states, especially the religious leaders fought tooth and nail against women’s suffrage, immigration, universal education and voting rights, especially for poor whites, who also for the most part were condemned to menial employment and hardscrabble farming whose social status was only just above that of African Americans. Those subjects, which are also very much a part of the modern Tea Party lexicon, each, could be addressed in its own article. But today I am focusing on the ideological differences between the North and the South related to the “particular institution” of slavery and briefly touch on other issues.

In his book Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1981 British theorist and military historian J.F.C. Fuller wrote of the American Civil War:

“As a moral issue, the dispute acquired a religious significance, state rights becoming wrapped up in a politico-mysticism, which defying definition, could be argued for ever without any hope of a final conclusion being reached.” [1]

That is why it impossible to simply examine the military campaigns and battles of the Civil War in isolation from the politics polices and even the philosophy and theology which brought it about. In fact the cultural, ideological and religious roots and motivations of conflict are profound indicators of how savage a conflict will be and to the ends that participants will go to achieve their ends.

Thus the study of the causes of the American Civil War, from the cultural, economic, social and religious aspects which divided the nation, helps us to understand how those factors influence politics, policy and the primal passions of the people which drive them to war.

The political ends of the Civil War came out of the growing cultural, economic, ideological and religious differences between the North and South that had been widening since the 1830s. The growing economic disparity between the slave and Free states became more about the expansion of slavery in federal territories as disunion and war approached. This was driven by the South’s insistence on both maintaining slavery where it was already legal and expanding it into new territories and the vocal abolitionist movement. This not only affected politics, it affected religion and culture.

As those differences grew and tensions rose “the system of subordination reached out still further to require a certain kind of society, one in which certain questions were not publicly discussed. It must give blacks no hope of cultivating dissension among the whites. It must commit nonslaveholders to the unquestioning support of racial subordination….In short, the South became increasingly a closed society, distrustful of isms from outside and unsympathetic to dissenters. Such were the pervasive consequences of giving top priority to the maintenance of a system of racial subordination.” [2]

Edmund Ruffin

The world was changed when Edmund Ruffin a 67 year old farm paper editor, plantation owner and ardent old line secessionist from Virginia pulled the lanyard which fired the first shot at Fort Sumter. Ruffin was a radical ideologue. He was a type of man who understood reality far better than some of the more moderate oligarchs that populated the Southern political and social elite. While in the years leading up to the war these men attempted to secure the continued existence and spread of slavery within the Union. Ruffin was not such a man. He and other radical secessionists believed that there could be no compromise with the north. He believed that in order to maintain the institution of slavery the slave holding states that those states had to be independent from the North.

Ruffin’s views were not unique to him, the formed the basis of how most slave owners and supporters felt about slavery’s economic benefits, Ruffin wrote:

“Still, even this worst and least profitable kind of slavery (the subjection of equals and men of the same race with their masters) served as the foundation and the essential first cause of all the civilization and refinement, and improvement of arts and learning, that distinguished the oldest nations. Except where the special Providence and care of God may have interposed to guard a particular family and its descendants, there was nothing but the existence of slavery to prevent any race or society in a state of nature from sinking into the rudest barbarism. And no people could ever have been raised from that low condition without the aid and operation of slavery, either by some individuals of the community being enslaved, by conquest and subjugation, in some form, to a foreign and more enlightened people.”[3]

The Ante-Bellum South was an agrarian society which depended on the free labor provided by slaves and in a socio-political sense it was an oligarchy that offered no freedom to slaves, discrimination against free blacks and little hope of social or economic advancement for poor and middle class whites. Over a period of a few decades, Northern states abolished slavery in the years after the United States had gained independence. In the years the before the war, the North embraced the Industrial Revolution leading to advances which gave it a marked economic advantage over the South. The population of the North also expanded at a clip that far outpaced the South as European immigrants swelled the population.

The divide was not helped by the various compromises worked out between northern and southern legislators. After the Missouri Compromise Thomas Jefferson wrote:

“but this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed indeed for the moment, but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.”[4]

The trigger for the increase in tensions was the war with Mexico in which the United States annexed nearly half of Mexico. The new territories were viewed by those who advocated the expansion of slavery as fresh and fertile ground for its spread. Ulysses S Grant noted the effects of the war with Mexico in his memoirs:

“In taking military possession of Texas after annexation, the army of occupation, under General [Zachary] Taylor, was directed to occupy the disputed territory. The army did not stop at the Nueces and offer to negotiate for a settlement of the boundary question, but went beyond, apparently in order to force Mexico to initiate war….To us it was an empire and of incalculable value; but it might have been obtained by other means. The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war.”[5]

In the North a strident abolitionist movement took root. It developed during the 1830s in New England as a fringe movement among the more liberal elites, inspired by the preaching of revivalist preacher Charles Finney who “demanded a religious conversion with a political potential more radical than the preacher first intended.” [6] Finney’s preaching was emboldened and expanded by the American Anti-Slavery Society founded by William Lloyd Garrison “which launched a campaign to change minds, North and South, with three initiatives, public speeches, mass mailings and petitions.” [7] Many of the speakers were seminary students and graduates of Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, who became known as “the Seventy” who received training and then “fanned out across the North campaigning in New England, Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, Indiana and Michigan” [8] where many received hostile receptions, and encountered violence. Garrison used his newspaper, The Liberator to “pledge an all-out attack on U.S. slavery.” [9]

Frederick Douglass

Garrison frequently traveled and conducted speaking engagements with Frederick Douglass, the most prominent African American in the nation and himself a former slave. Douglass escaped slavery in 1838 and in 1841 he was “recruited by an agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society; four years later he published his Narrative of the Life of a Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Within a decade he had become the most famous African American on the continent, and one of slavery’s most deadly enemies.” [10]

The abolition movement aimed to not only stop the spread of slavery but to abolish it. The latter was something that many in the North who opposed slavery’s expansion were often either not in favor of, or indifferent to. The movement was given a major boost by the huge popularity of Harriett Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin “a vivid, highly imaginative, best-selling, and altogether damning indictment of slavery” [11] the abolitionist movement gained steam and power and “raised a counterindignation among Southerners because they thought Mrs. Stowe’s portrait untrue…” [12] The images in Stowe’s book “were irredeemably hostile: from now on the Southern stereotype was something akin to Simon Legree.” [13]

The leaders of the Abolitionist movement who had fought hard against acts the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision were now beginning to be joined by a Northern population that was becoming less tolerant of slavery and the status quo. With the formation of the Republican Party in 1854, a party founded on opposition to the expansion of slavery in the territories found a formidable political voice and became part of a broad coalition of varied interests groups whose aspirations had been blocked by pro-slavery Democrats. These included “agrarians demanding free-homestead legislation, Western merchants desiring river and harbor improvements at federal expense, Pennsylvania ironmasters and New England textile merchants in quest of higher tariffs.” They also made headway in gaining the support of immigrants, “especially among the liberal, vocal, fiercely anti-slavery Germans who had recently fled the Revolution of 1848.” [14] One of those German immigrants, Carl Schurz observed that “the slavery question” was “not a mere occasional quarrel between two sections of the country, divided by a geographic line” but “a great struggle between two antagonistic systems of social organization.” [15]

In light of the threat posed to slavery by the emerging abolitionist movement forced slaveholders to shift their defense of slavery from it being simply a necessary evil. Like in the North where theology was at the heart of many abolitionist arguments, in the South theology was used to enshrine and defend the institution of slavery. The religiously based counter argument was led by the former Governor of South Carolina, John Henry Hammond. Hammond’s arguments included biblical justification of blacks being biologically inferior to whites and slavery being supported in the Old Testament where the “Hebrews often practiced slavery” and in the New testament where “Christ never denounced servitude.” [16] Hammond warned:

“Without white masters’ paternalistic protection, biologically inferior blacks, loving sleep above all and “sensual excitements of all kinds when awake” would first snooze, then wander, then plunder, then murder, then be exterminated and reenslaved.” [17]

Others in the South, including politicians, pundits and preachers “were preaching “that slavery was an institution sanction by God, and that even blacks profited from it, for they had been snatched out of pagan and uncivilized Africa and been given the advantages of the gospel.” [18]

Slave owners frequently expressed hostility to independent black churches and conducted violence against them, and “attacks on clandestine prayer meetings were not arbitrary. They reflected the assumption (as one Mississippi slave put it) “that when colored people were praying [by themselves] it was against them.” [19] But some Southern blacks accepted the basic tenets do slave owner-planter sponsored Christianity. Douglass wrote “many good, religious colored people who were under the delusion that God required them to submit to slavery and wear their chains with weakness and humility.” [20]

The political and cultural rift began to affect entire church denominations, beginning with the Methodists who in “1844 the Methodist General Conference condemned the bishop of Georgia for holding slaves, the church split and the following year saw the birth of the Methodist Episcopal Church.” The Baptists were next, when the Foreign Mission Board “refused to commission a candidate who had been recommended by the Georgia Baptist Convention, on the ground that he owned slaves” [21] resulting in the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention. Finally in 1861, “reflecting the division of the nation, the Southern presbyteries withdrew from the Presbyterian Church and founded their own denomination.” [22] Sadly, the denominational rifts persisted until well into the twentieth century. The Presbyterians and Methodists both eventually reunited but the Baptists did no. The Southern Baptist Convention is now the largest Protestant denomination in the United States and many of its preachers active in often divisive conservative social and political causes. The denomination that it split from, the American Baptist Convention, though much smaller remains a diverse collection of conservative and progressive local churches. Some of these are still in the forefront of the modern civil rights movement, including voting rights, women’s rights and LGBT issues, all of which find some degree of opposition in the Southern Baptist Convention.

As the 1850s wore on the divisions over slavery became deeper and voices of moderation retreated. The trigger for the for the worsening of the division was the political battle regarding the expansion of slavery, even the status of free blacks in the north who were previously slaves, over whom their owners asserted their ownership. Southerners considered the network to help fugitive slaves escape to non-slave states, called the Underground Railroad “an affront to the slaveholders pride” and “anyone who helped a man or woman escape bondage was simply a thief” who had robbed them of their property and livelihood, as an “adult field hand could cost as much as $2000, the equivalent of a substantial house.” [23]

Dred Scott

In 1856 the Supreme Court, dominated by southern Democrats ruled in favor of southern views in the Dred Scott decision one pillar of which gave slavery the right to expand by denying to Congress the power to prohibit slavery in Federal territories. The decision in the case, the majority opinion which was written by Chief Justice Roger Taney was chilling, not only in its views of race, but the fact that blacks were perpetually property without the rights of citizens. Taney wrote:

“Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen?…It is absolutely certain that the African race were not included under the name of citizens of a state…and that they were not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word “citizens” in the Constitution, and therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings, who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remain subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them” [24]

The effect of the ruling on individuals and the states was far reaching. “No territorial government in any federally administered territory had the authority to alter the status of a white citizen’s property, much less to take that property out of a citizen’s hands, without due process of law or as punishment for some crime.” [25] Free slaves were no longer safe, even in Free States from the possibility of being returned to slavery, because they were property.

But the decision had been influenced by President-Elect James Buchanan’s secret intervention in the Supreme Court deliberations two weeks before his inauguration. Buchanan hoped by working with the Justices that he save the Union from breaking apart by appeasing slave owners and catering to their agenda. The president-elect wanted to know not only when, but if the Court would save the new administration and the Union from the issue of slavery in the territories. Would the judges thankfully declare the explosive subject out of bounds, for everyone who exerted federal power? The shattering question need never bother President Buchanan.” [26]In his inaugural address he attempted to camouflage his intervention and “declared that the Court’s decision, whatever it turned out to be, would settle the slavery issue forever.” [27]

This ignited a firestorm in the north where Republicans now led by Abraham Lincoln decried the decision and southerners basked in their judicial victory. Northerners quite rightly feared that an activist court would rule to deny their states the right to forbid slavery. As early as 1854 Lincoln posed the idea that the Declaration of Independence was “the standard maxim of free society …constantly spreading and deepening its influence,” ultimately applicable “to peoples of all colors everywhere.” [28]

But after the Dred Scott decision Lincoln warned that the Declaration was being cheapened and diluted “to aid in making the bondage of the Negro universal and eternal….All the powers of the earth seem rapidly combining against him. Mammon is after him; ambition follows, and philosophy follows, and the theology of the day is fast joining the cry. They have him in his prison house;…One after another they have closed the heavy doors upon him…and they stand musing as to what invention, in all the dominions of mind and matter, can be produced the impossibility of his escape more complete than it is.” [29]

In response to the decision the advocates of the expansion of slavery not only insisted on its westward expansion in Federal territories but to Panama, Nicaragua and Cuba as well. In 1857 Jefferson Davis further provoked northern ire when he insisted that “African Slavery as it exists in the United States is a moral, a social, and a political blessing.” [30]

Jefferson Buford

Southern leaders poured political, human and economic capital into the struggle for the imposition of slavery on the Kansas Territory. Victory in Kansas meant “two new U.S. Senators for the South. If a free labor Kansas triumphed, however, the North would gain four senators: Kansas’s immediately and Missouri’s soon.” [31] Rich Southerners recruited poor whites to fight their battles to promote the institution of slavery. Jefferson Buford of Alabama recruited hundreds of non-slaveholding whites to move to Kansas. Buford claimed to defend “the supremacy of the white race” he called Kansas “our great outpost” and warned that “a people who would not defend their outposts had already succumbed to the invader.” [32] To this end he and 415 volunteers went to Kansas, where they gained renown and infamy as members of “Buford’s Cavalry.” The day they left Montgomery they were given a sendoff. Each received a Bible, and the “holy soldiers elected Buford as their general. Then they paraded onto the steamship Messenger, waving banners conveying Buford’s twin messages: “The Supremacy of the White Race” and “Kansas the Outpost.” [33] His effort ultimately failed but he had proved that “Southern poor men would kill Yankees to keep blacks ground under.” [34]

The issue in Kansas was bloody and full of political intrigue over the Lecompton Constitution which allowed slavery, but which had been rejected by a sizable majority of Kansas residents, so much so that Kansas would not be admitted to the Union until after the secession of the Deep South. But the issue so galvanized the North that for the first time a coalition of “Republicans and anti-Lecompton Douglas Democrats, Congress had barely turned back a gigantic Slave Power Conspiracy to bend white men’s majoritarianism to slavemaster’s dictatorial needs, first in Kansas, then in Congress.” [35]

Taking advantage of the judicial ruling Davis and his supporters in Congress began to bring about legislation not just to ensure that Congress could not “exclude slavery” but to protect it in all places and all times. They sought a statute that would explicitly guarantee “that slave owners and their property would be unmolested in all Federal territories.” This was commonly known in the south as the doctrine of positive protection, designed to “prevent a free-soil majority in a territory from taking hostile action against a slave holding minority in their midst.” [36]

Other extremists in the Deep South had been long clamoring for the reopening of the African slave trade. In 1856 a delegate at the 1856 commercial convention insisted that “we are entitled to demand the opening of this trade from an industrial, political, and constitutional consideration….With cheap negroes we could set hostile legislation at defiance. The slave population after supplying the states would overflow to the territories, and nothing could control its natural expansion.” [37] and in 1858 the “Southern Commercial Convention…”declared that “all laws, State and Federal, prohibiting the African slave trade, out to be repealed.” [38] The extremists knowing that such legislation would not pass in Congress then pushed harder; instead of words they took action.

In 1858 there took place two incidents that brought this to the fore of political debate. The schooner Wanderer owned by Charles Lamar successfully delivered a cargo of four hundred slaves to Jekyll Island, earning him “a large profit.” [39] Then the USS Dolphin captured “the slaver Echo off Cuba and brought 314 Africans to the Charleston federal jail.” [40] The case was brought to a grand jury who had first indicted Lamar were so vilified that “they published a bizarre recantation of their action and advocated the repeal of the 1807 law prohibiting the slave trade. “Longer to yield to a sickly sentiment of pretended philanthropy and diseased mental aberration of “higher law” fanatics…” [41] Thus in both cases juries and judges refused to indict or convict those responsible.

There arose in the 1850s a second extremist movement in the Deep South, this to re-enslave free blacks. This effort was not limited to fanatics, but entered the Southern political mainstream, to the point that numerous state legislatures were nearly captured by majorities favoring such action. [42] That movement which had appeared out of nowhere soon fizzled, as did the bid to reopen the slave trade, but these “frustrations left extremists the more on the hunt for a final solution” [43] which would ultimately be found in secession.

Abraham Lincoln

Previously a man of moderation Lincoln laid out his views in the starkest terms in his House Divided speech given on June 16th 1858. Lincoln understood, possibly with more clarity than others of his time that the divide over slavery was deep and that the country could not continue to exist while two separate systems contended with one another. The Union Lincoln “would fight to preserve was not a bundle of compromises that secured the vital interests of both slave states and free, …but rather, the nation- the single, united, free people- Jefferson and his fellow Revolutionaries supposedly had conceived and whose fundamental principles were now being compromised.” [44] He was to the point and said in clear terms what few had ever said before and which even some in his own Republican Party did not want to use because they felt it was too divisive:

“If we could first know where we are and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year since a policy was initiated with the avowed object and confident promise of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only not ceased but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; I do not expect the house to fall; but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the states, old as well as new, North as well as South.” [45]

Part of the divide was rooted in how each side understood the Constitution. For the South it was a compact among the various states, or rather “only a league of quasi independent states that could be terminated at will” [46] and in their interpretation States Rights was central. In fact “so long as Southerners continued to believe that northern anti-slavery attacks constituted a real and present danger to Southern life and property, then disunion could not be ruled out as an ugly last resort.” [47]

But such was not the view in the North, “for devout Unionists, the Constitution had been framed by the people rather than created as a compact among the states. It formed a government, as President Andrew Jackson insisted of the early 1830s, “in which all the people are represented, which operates directly on the people individually, not upon the States.” [48] Lincoln like many in the North understood the Union that “had a transcendent, mystical quality as the object of their patriotic devotion and civil religion.” [49] His beliefs can be seen in the Gettysburg Address where he began his speech with the words “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal…” To Lincoln and others the word disunion “evoked a chilling scenario within which the Founders’ carefully constructed representative government failed, triggering “a nightmare, a tragic cataclysm” that would subject Americans to the kind of fear and misery that seemed to pervade the rest of the world.” [50]

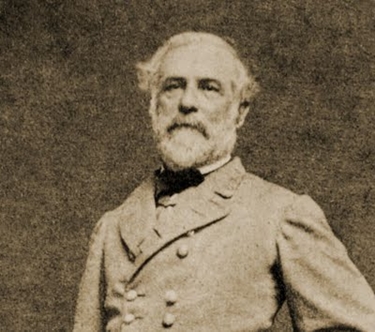

Even in the South there was a desire for the Union and a fear over its dissolution, even among those officers like Robert E. Lee who would resign his commission and take up arms against the Union in defense of his native state. Lee wrote to his son Custis in January 1861, “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than the dissolution of the Union…I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation…Secession is nothing but revolution.” But he added “A Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets has no charms for me….” [51] The difference between Lee and others like him and Abraham Lincoln was how they viewed the Union, views which were fundamentally opposed.

In the North there too existed an element of fanaticism. While “the restraining hand of churches, political parties and familial concerns bounded other antislavery warriors,” [52] and while most abolitionists tried to remain in the mainstream and work through legislation and moral persuasion to halt the expansion of slavery with the ultimate goal of emancipation, there were fanatical abolitionists that were willing to attempt to ignite the spark which would cause the powder keg of raw hatred and emotion to explode. Most prominent among these men was John Brown.

John Brown

Brown was certainly “a religious zealot…but was nevertheless every much the product of his time and place….” [53] Brown was a veteran of the violent battles in Kansas where he had earned the reputation as “the apostle of the sword of Gideon” as he and his men battled pro-slavery settlers. Brown was possessed by the belief that God had appointed him as “God’s warrior against slaveholders.” [54] He despised the peaceful abolitionists and demanded action. “Brave, unshaken by doubt, willing to shed blood unflinchingly and to die for his cause if necessary, Brown was the perfect man to light the tinder of civil war in America, which was what he intended to do.”[55]

Brown’s attempt to seize 10,000 muskets at the Federal armory in Harper’s Ferry Virginia in order to ignite a slave revolt was frustrated and Brown captured, by a force of U.S. Marines led by Colonel Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart. Brown was tried and hung, but his raid “effectively severed the country into two opposing parts, making it clear to moderates there who were searching for compromise, that northerner’s tolerance for slavery was wearing thin.” [56]

It now did not matter that Brown was captured, tried, convicted and executed for his raid on Harper’s Ferry. He was to be sure was “a half-pathetic, half-mad failure, his raid a crazy, senseless exploit to which only his quiet eloquence during trial and execution lent dignity” [57] but his act was the watershed from which the two sides would not be able to recover, the population on both sides having gone too far down the road to disunion to turn back.

Brown had tremendous support among the New England elites, the “names of Howe, Parker, Emerson and Thoreau among his supporters.” [58] To many abolitionists he had become a martyr, “but to Frederick Douglass and the negroes of Chatham, Ontario, nearly every one of whom had learned something from personal experience on how to gain freedom, Brown was a man of words trying to be a man of deeds, and they would not follow him. They understood him, as Thoreau and Emerson and Parker never did.”

But to Southerners Brown was the symbol of an existential threat to their way of life. In the North there was a nearly religious wave of sympathy for Brown, and the “spectacle of devout Yankee women actually praying for John Brown, not as a sinner but as saint, of respectable thinkers like Thoreau and Emerson and Longfellow glorifying his martyrdom in Biblical language” [59] horrified Southerners, and drove pro-Union Southern moderates into the secession camp.

The crisis continued to fester and when Lincoln was elected to the Presidency in November 1860 with no southern states voting Republican the long festering volcano erupted. It did not take long before southern states began to secede from the Union. South Carolina was first, followed by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. Many of the declarations of causes for secession made it clear that slavery was the root cause. The declaration of South Carolina is typical of these and is instructive of the basic root cause of the war:

“all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. He is to be entrusted with the administration of the common Government, because he has declared that that “Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free,” and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction.”[60]

Throughout the war slavery loomed large. In his First Inaugural Address Lincoln noted: “One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.”[61] Of course he was right, and his southern opponents agreed.

Alexander Stephens

Alexander Stephens the Vice President of the Confederacy noted in his Cornerstone Speech of March 21st 1861 that: “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner- stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition. [Applause.] This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”[62]

Thus the American ideological war was born, as J.F.C. Fuller wrote:

“At length on 12th April, the tension could no longer bear the strain. Contrary to instructions, in the morning twilight, and when none could see clearly what the historic day portended, the Confederates in Charleston bombarded Fort Sumter, and the thunder of their guns announced that the argument of a generation should be decided by the ordeal of war. A war, not between two antagonistic political parties, but a struggle to the death between two societies, each championing a different civilization…”[63]

After the bloody battle of Antietam, Lincoln published the emancipation proclamation in which he proclaimed the emancipation of slaves located in the Rebel states, and that proclamation had more than a social and domestic political effect, it ensured that Britain would not intervene.

In his Second Inaugural Address Lincoln discussed the issue of slavery as being the cause of the war:

“One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”[64]

When Edmund Ruffin pulled the lanyard of the cannon that fired the first shot at Fort Sumter it marked the end of an era and despite Ruffin, Stephens and Davis’ plans gave birth to what Lincoln would describe as “a new birth of freedom.”

When the war ended with the Confederacy defeated and the south in ruins, Ruffin still could not abide the result. In a carefully crafted suicide note he sent to his son the bitter and hate filled old man wrote on June 14th 1865:

“… And now with my latest writing and utterance, and with what will be near my last breath, I here repeat and would willingly proclaim my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule — to all political, social and business connections with Yankees, and the perfidious, malignant and vile Yankee race.” [65]