Friends of Padre Steve’s World

I am traveling with my students to Gettysburg this weekend and happen to be posting my newest additions to my text, these dealing with the battles for Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill which occurred on the night of July 2nd and early morning of July 3rd 1863. I hope you enjoy.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

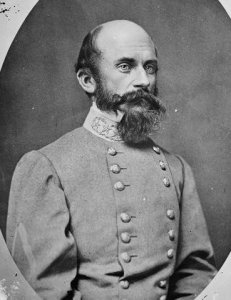

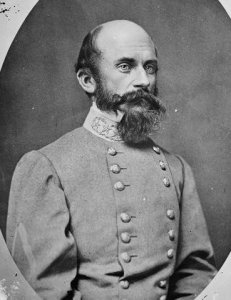

Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, C.S.A

During the day of July second little happened on Ewell’s front, an officer in Maryland Steuart’s brigade wrote “Greatly did officers and men marvel as morning, noon, and afternoon passed in inaction – on our part, not the enemy’s, for, as we well knew, he was plying axe and pick and shovel….” [1] . Though he had persuaded General Lee to leave his troops in place in order to assist Longstreet’s attack if the situation permitted, Ewell remained mostly inactive on July second with the exception of some skirmishing and a battle between the Stonewall Brigade and Gregg’s division of Federal Cavalry on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge about two and a half miles east of the town.

Lee was becoming more frustrated at the inaction of his corps commanders, and wanted Ewell to be able to support Longstreet’s attack, desire it to “make a simultaneous demonstration upon the enemy’s right, to be converted into a real attack should opportunity offer.” [2] But Ewell and his division commanders who had opposed the attack the previous evening, still were against it. Despite his misgivings, Ewell had been stung by Lee’s criticism the night before, and “was eager to make a redemptive showing today.” [3] Accordingly after his meeting with Lee around nine a.m. he began to position his units for the diversion that he hoped would turn into an opportunity to attack. After his conversation with Lee, Ewell “suffered between fear of another failure and an inner goad to commit his troops to action. His unsettled state could not have been helped by the long wait for the sound of Longstreet’s guns, which frayed the nerves.” [4]

Second Corps was deployed in a rough semi-circle to the east, north, and west of Culp’s and Cemetery Hill. The four brigades of Allegheny Johnson’s division which had not been present on the first day of battle occupied the area to the east of Culp’s Hill north of the Hanover Road. From there its skirmishers occasionally clashed with Federal skirmishers, while otherwise spending an uneventful day.

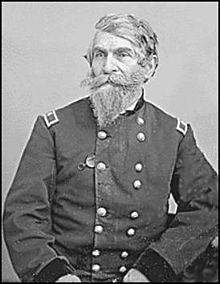

Edward “Old Allegheny” Johnson was an old regular army officer. Johnson was born in Salisbury, Virginia in 1816. He was a graduate of the West Point class of 1838 along with P.T.G. Beauregard and Irvin McDowell. Johnson had a solid record of service in the old Army, he served in the Seminole Wars and received brevet promotions to Captain and Major during the Mexican War. Like many officers that remained in the army after Mexico he served on the frontier on the Great Plains.

Johnson resigned his commission when Virginia seceded from the Union and was appointed Colonel of the 12th Georgia Infantry. [5] He was promoted to Brigadier General in December 1861. Johnson commanded a brigade sized force with the grand name of “the Army of the Northwest” which fell under the command of Stonewall Jackson.[6] He held the crest of the Allegheny Mountains so well with his small force that he was given the “nom de guerre “Allegheny” Johnson.” [7] Johnson was wounded in the ankle at the Battle of McDowell on May 8th 1862, but the wound took nearly a year to heal, imperfectly at that. He was a rather “curious, somewhat uncouth, and strangely fascinating man” [8] who made the most of his convalescence in Richmond, making pass after pass, and occasional proposals to women about town. He was a favorite of Stonewall Jackson who insisted that he be promoted to Major General and be given command of a division.

The division that Johnson took over was the former division of Jackson, and “many of these regiments had fought in “Stonewall” Jackson’s original division, and the troops enjoyed an spirit as exalted as their combat record.” [9] When Ewell was promoted to command Second Corps after Jackson’s death following the Battle of Chancellorsville Johnson was named as commander. Despite his wealth of experience in the pre-war army and service with Jackson in the Valley, Johnson was an outsider to the division and he commanded men “who knew him by reputation only.”[10] Like so many other Confederate division commanders at Gettysburg he had never before commanded a division, so he came to the position “with no real experience above the brigade level.” Likewise he was “unfamiliar with the qualities and limitations of his four new brigadiers,” [11] having served with none of them prior to the Gettysburg campaign. Two, “Maryland” Steuart, and James Walker were experienced brigade commanders, J.M. Jones was a former regular who due to problems with alcohol had only served in staff positions before being promoted to command a brigade, and Colonel Jesse Williams, a regimental commander with little experience had taken a brigade as there was no one else qualified.

Despite this, Johnson became quite popular with his men. Because Johnson walked with a limp and used a long staff to help him walk, it was said that: “his boys sometimes call him “Old Club.” [12] As a division commander “Johnson developed a reputation that when he threw his troops into battle, then struck with the punch of a sledgehammer, exactly the way Lee wanted his commanders to fight.” [13] Johnson “does well in nearly all his fights, hits hard and wins the confidence of his men.” [14] Gettysburg was his first test as a division commander, but not one that gave Johnson a real opportunity to excel.

Jubal Early’s division lay to the north of both Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, with the brigades of Hays and Hoke posted “east of Baltimore Street in the ravine of Winebrenner’s Run,” where it “spent a miserable day,” as the ravine was “deep enough to cut off cooling breezes, its slopes were bare of trees, and the July sun warmed the Confederates without mercy. It was a debilitating and dangerous place. General Ewell wanted to pull Hays’s brigade back when it became apparent that the attack would be delayed, but he could not do so without risk of great loss. But staying there was not much better because, as Lt. William Seymour observed, it was almost death for a man to stand upright. ” [15]

“Old Jube” Early was an unusual character. He was described similarly by many to Dick Ewell in his gruffness and eccentrics. However, unlike Ewell, who was modest and charitable, Early was “ambitious, critical, and outspoken to the point of insubordination. Under certain circumstances he could be devious and malevolent.” [16] James Longstreet’s aide Moxey Sorrel wrote of him: “Jubal Early….was one of the ablest soldiers in the army. Intellectually he was perhaps the peer of the best for strategic combinations, but he lacked the ability to handle troops effectively in the field….His irritable disposition and biting tongue made him anything but popular.” [17] Despite this, Early had proved himself as a brigade commander and acting division commander and Lee referred to him affectionately as “my bad old man.” [18]

Early was the son of a tobacco planter in Franklin County Virginia. He was born in 1816 who had served in the Virginia legislature and was a Colonel of militia. Growing up he had an aptitude for science and mathematics. He was accepted into West Point in 1833 at the age of seventeen. He was a good student, but had poor marks for conduct and graduated in the eighteenth of fifty cadets in the class of 1837. His fellow students included Joe Hooker, John Sedgwick, Braxton Bragg, and John Pemberton, later, the doomed defender of Vicksburg. Also in the class was Lewis Armistead, with whom the young Early had an altercation that led to Armistead breaking a plate over his head in the mess hall. For the offense Armistead was dismissed from the academy.

He was commissioned into the artillery on graduation in 1837. However, after experiencing life in the active duty army, including service in the in the Seminole War, Early left the army and became a highly successful lawyer and active Whig politician. He served in the Mexican war as a Major with Virginia volunteers. Unlike some of his classmates, and later contemporaries in the Civil War, Early, and his men did not see combat, instead, serving on occupation duty. In Mexico Zachary Taylor made Early the “military governor of Monterrey, a post that he relished and filled with distinction.” [19]

After his service in Mexico, Early returned to Virginia, where he returned to his legal practice, serving as a prosecuting attorney. He also entered local politics where he served as a Whig in the Virginia legislature.

During his time in Mexico, Early contracted rheumatic fever, which left him with painful rheumatoid arthritis for the rest of his life. Due to it he “stooped badly and seemed so much older than his years that his soldiers promptly dubbed him “Old Jube” or Old Jubilee.” [20]

Jubal Early was “notoriously a bachelor and at heart a lonely man.” Unlike many Confederate officers he had “no powerful family connections, and by a somewhat bitter tongue and rasping wit” isolated himself from his peers.[21]

Likewise, in an army dominated by those with deep religious convictions, Early was avowedly irreligious and profane, though he did understand the importance of “the value of religion in keeping his soldiers’ spirits up” and as commander of the Army of the Valley, issued orders for a stricter keeping of the Sabbath. [22] Lee’s adjutant Walter Taylor wrote of him “I feared our friend Early wd not accomplish much because he is such a Godless man. He is a man who utterly sets at defiance all moral laws & such a one heaven cannot favor.” [23] That being said Porter Alexander praised Early and noted that his “greatest quality perhaps was the fearlessness with which he fought against all odds & discouragements.” [24]

Jubal Early was a Whig, and a stalwart Unionist who opposed Virginia’s secession, voting against it because he found it “exceedingly difficult to surrender the attachment of a lifetime to that Union which…I have been accustomed to look upon (in the language of Washington) as the palladium of the political safety and prosperity of the country.” [25] Nonetheless, like so many others he volunteered for service after Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to crush the rebellion.

Robert E. Lee “appreciated Early’s talents as a soldier and displayed personal fondness for his cantankerous and profane Lieutenant …who only Stonewall Jackson received more difficult assignments from Lee.” [26] Early was the most influential of Ewell’s division commanders, and his “record in battle prior to Gettysburg was unsurpassed.” [27]

On Ewell’s left, Robert Rodes’s division, which had taken such a brutal beating at Oak Hill on July 1st lay to the west and north of Cemetery Hill in the town itself. “Doles’s, Iverson’s, and Ramseur’s brigades of Rodes’s division occupied Middle Street west from Baltimore Street to the edge of the town. O’Neal’s brigade was along the railroad bed to the right and rear, and Daniel’s brigade occupied the ridge at the seminary.” [28]

Ewell also took the time to scout for artillery positions, the only two that offered any support were on Seminary Ridge to the west and on Brenner’s Hill to the north, and on Brenner’s Hill he deployed Major Joseph Latimer’s artillery battalion. Latimer was not yet twenty years old at Gettysburg. Latimer had been a seventeen year-old student at the Virginia Military Institute at the outbreak of the war and volunteered to help a newly formed artillery battery. He impressed other officers enough that he was given a commission as a First Lieutenant shortly after turning eighteen, and promoted to Captain and command of Virginia’s Courtney Artillery in March of 1862. “Sometimes called “the “Boy Major” and “Young Napoleon,” Latimer had won the respect of the entire army for his skill and bravery,” [29] and he was often cheered by the infantry as he rode by. His battlefield performance was such that he was promoted to Major in March 1863, and given command acting command of the battalion of Lieutenant Colonel R. Snowden Andrews who had been wounded at Winchester.

The lack of good positions to place his guns meant that Ewell’s artillery Chief, Colonel J. Thompson Brown had to work hard to find suitable firing positions for all of his guns. Some he placed on Seminary Ridge, and others on Brenner’s Hill. Brown “could get only forty-eight of the eighty or so guns of the Second Corps placed for action. Of these only thirty-two became actively engaged on July 2nd.” [30]

Around four o’clock Latimer’s batteries commenced firing at the Federal positions on Cemetery Hill, provoking a storm of counter-battery fire from Colonel Wainwright’s First Corps guns. The confederate batteries were placed on Brenner’s Hill, which was devoid of cover and about fifty feet lower than the opposing Federal batteries on Cemetery Hill. The Confederates opened fire and Wainwright noted the effectiveness of the Confederate fire from Brenner’s Hill, considering it some “of the most accurate we had seen,” and that the weight of shell between the two sides was about equal, but Latimer’s gunners had no chance. Heavy fire from Wainwright’s batteries “immediately answered him and soon found the range. Within five minutes one of his caissons exploded. Twenty-five men went down in the Allegheny Roughs. Gunners in other batteries began dropping, and it became evident that the open hill was too hot a place to stay.” [31]

The Union fire was most effective and caused great damage to the Confederate batteries. Wainwright wrote, “Still we were able to shut them up, and actually drive them from the field in about two hours.” [32] The highly accurate Federal fire “smothered the enemy gunners and forced them to pull back from the hill out of effective range.” [33]A Confederate artilleryman from the Chesapeake Artillery described the position as “simply a hell infernal,” and wrote “we were directly opposed by some of the finest batteries in the regular service of the enemy, which batteries moreover, held a position to which ours was a molehill. Our shells ricocheted over them, whilst theirs plunged into the devoted battalion, carrying death and destruction everywhere.” [34] Latimer realized that he could not keep up the fight and told General Johnson “that he could no longer hold his posting on Brenner’s Hill. He was told to evacuate all but four guns, which would be used to support the infantry.” [35] While directing the fire of the remaining battery Latimer was mortally wounded by an artillery burst. He died a month later, depriving the Confederacy of one of its most promising young artillery officers. Ewell, who admired him greatly wrote, “Though not yet twenty-one when he fell, his soldierly qualities had impressed me as deeply as those of any officer in my command.” [36] It was “a high price to pay for confirming what should have been apparent before the one-sided contest ever began.” [37] The Confederate cannonade achieved nothing. “As a demonstration it quite failed to distract the Federals, with Meade continuing to reinforce against Longstreet’s offensive. It also quite failed to uncover any obvious “opportunity” for a “real attack” against the Federal right.” [38]

Despite the beating Latimer’s battalion had suffered Ewell was now determined to play his part in the day’s action. During the tense waiting period before the attack Ewell had advised his division commanders “that they should begin their demonstration when they heard Longstreet’s guns. He left to their discretion whether or not they should change the threat into a real assault.” [39] As such he failed to coordinate Ewell made a critical mistake by failing to ensure that Johnson, Early, and Rodes coordinated any offensive that they should undertake. As a result the effort of the Second Corps devolved into three separate actions none of which were coordinated, with fatal results.

As Latimer’s attack ended “quiet, quiet, along with the fading sun, descended on Slcoum’s front,” [40] Ewell and his troops prepared for battle, the impact of Longstreet’s assaults on the Federal left were beginning to be felt on Culp’s Hill.

Notes

[1] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.325

[2] Pfanz, Donald. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier’s Life University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 1998 p.314

[3] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.514

[4] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.231

[5] Ibid. Warner Generals in Gray p.159 Others sources state this is the 12th Virginia and I cannot find a consensus.

[6] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.123

[7] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.170

[8] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.459

[9] Greene, A. Wilson “A Step All-Important and Essential Element of Victory” Henry Slocum and the Twelfth Corps on July-1-2 in The Second Day at Gettysburg: Essays on Confederate and Union Leadership edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio and London, 1993 p.111

[10] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.459

[11] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg pp.269-270

[12] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.47

[13] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.345

[14] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.47

[15] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.127

[16] Ibid. Pfanz Richard S. Ewell p.268

[17] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.206

[18] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.155

[19] Ibid. Osborne Jubal p.28

[20] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.83

[21] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenants p.33

[22] Ibid. Osborne Jubal p.385

[23] Ibid. Girardi. The Civil War Generals p.207

[24] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p.397

[25] Ibid. Osborne Jubal p.50

[26] Gallagher, Gary W. Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy; Frank L Klement Lecture, Alternate Views of the Sectional Conflict Marquette University Press Marquette WI 2003 p.11

[27] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.256

[28] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill p.128

[29] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 p.159

[30] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command p.429

[31] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.232

[32] Wainwright, Charles S. A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright 1861-1865 edited by Allan Nevins, Da Capo Press, New York 1998 p.243

[33] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.428

[34] Ibid. Pfanz Ewell p.316

[35] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.283

[36] Ibid. Pfanz Ewell p.316

[37] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.515

[38] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.283

[39] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation pp.231-232

[40] Ibid. Greene “A Step All-Important and Essential Element of Victory” p.113