Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

Yesterday I posted a section of my Civil War and Gettysburg text with a revised section dealing with conscription and the draft in both the Union and the Confederacy. Today I am posting a further revised and expanded section on the Confederate conscription acts and their effect on the war, as well as resistance to them. I think that you will like it.

Have a great Wednesday,

Peace

Padre Steve+

The states which made up the Confederacy went to war with great aplomb in the spring and summer of 1861. The staunch secessionist fire-eaters predicted a quick victory, but they were badly mistaken, and after Bull Run that Union galvanized itself for a long war. A “quick and easy war like the one most staunch secessionists predicted might have required few soldiers to fight it.” [1] But since many of the men who had led their states into secession and war expected that with a few victories that the Federal government would acquiesce to their claims of independence few plans were made for a long war, but even so “the recruiting inducements of 1861 had never adequately filled the ranks or assured that the twelve-month enlistees of 1861 would remain.” [2] As the war dragged on many men became increasingly hesitant to serve, the “enthusiasm and bravado of the war’s early months increasingly gave way to hesitation, reticence, and the discovery that one’s presence was urgently needed someplace other than the battlefield.” [3]

As the war continued into 1862 and the Union continuing to build and deploy armies a sense of gloom built even as the spring flowers bloomed across the Confederacy. A soldier serving with the Stonewall Brigade wrote, “The romance of the thing is entirely worn off… not only with myself but with the whole army.” [4] In the East the army of George McClellan was nearing Richmond and in the West the unexpected “loss of Forts Henry and Donaldson, followed by the failure to redeem the Tennessee River at Shiloh and the fall of New Orleans badly jolted Southern complacency.” [5] Drastic measures were required and the Confederate Congress began to debate a conscription act in order to meet the manpower needs of the Confederate armies, a Confederate General wrote that the Confederacy must embrace a total war, “in which the whole population and the whole production… are to be put on a war footing, where every institution is made auxiliary to war.” [6] But the nature of the Confederacy itself precluded such a total effort as each state, and each economic interest, be it the planters, or the railroads fought to maintain their independence from edicts coming out of Richmond.

Robert E. Lee who was serving as military advisor to Jefferson Davis recognized that the Confederacy could not survive without conscription and put Major Charles Marshall, of his staff, who had been a lawyer in civilian life, to work “to draw up a bill providing for the conscription of all white males between eighteen and forty-five years of age.” [7] On March 28th 1862 Jefferson Davis proposed a conscription act to the Confederate Congress.

The proposal aroused an uproar throughout the South. Thomas Cobb of Georgia condemned the bill in Congress and proclaimed that it was “caused by the imbecility of the government,” accusing Davis and his toadies” of ignoring him when he warned earlier that something had to be done to lure those volunteers of 1861 into staying in the service.” [8] He condemned the measure of compelling men to serve. Vice President Alexander Stephens objected as he believed that the act “violated most basic principles that had underlain secession and the Confederacy’s creation, including state sovereignty and individual autonomy.” [9]

Davis was being worn out both physically and emotionally by the demands of the war, and by the opposition of the fire-eaters who often referred to him as a despot and tyrant, and wrote to a friend, “When everything is at stake and the united power of the South alone can save us, it is sad to know that such men can deal in such paltry complaints and tax their ingenuity to slander because they are offended in not getting office…. If we can achieve our independence, the office seekers are welcome to the one I hold.” [10] But aided by influential members of the Congress, many of whom had no love for Davis, including Senator Louis Wigfall of Texas, but Wigfall grasped the gravity of the situation and need for fresh manpower. Wigfall was committed “to the military and preoccupied with pushing the war vigorously, he saw a draft as the only way to meet his ends.” [11] Though he was opposed by the most extreme of the state’s rights members, Wigfall forcefully argued for the act, he warned his opponents to “cease child’s play…. The enemy are in some portions of almost every State in the Confederacy…. Virginia is enveloped by them. We need a large army. How are you going to get it?… No man has individual rights, which come into conflict with the welfare of the country.” [12]

On April 16th the Confederate Congress passed the Conscription Act of 1862 which in the process of being passed “was amended and mangled. Provision was made for the election of officers in reenlisted commands, and other useless paraphernalia of bounty and furlough act were loaded on it. The upper age-limit was reduced from forty-five to thirty-five years, and a bill allowing liberal exemption was soon adopted.” [13] In deference to the demands of the state’s-rights advocates for a measure of control of conscription, “enrollment and drafting would be administered by state officials though under Confederate supervision, and drafted men would be assigned to units of their own states. In deference to a historic custom of the militia, persons not liable for service could act as substitutes for those who were liable.” [14]

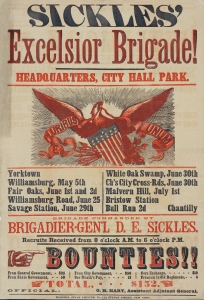

Even so the act was the first conscription act ever enacted in the history of the United States. The Southern press applauded its intentions but had sharp words regarding its weaknesses, especially after second act, detailing numerous exemptions was passes a few days later. Some soldiers who had been serving since the war began were angry at Congress and one South Carolina soldier asked “if the volunteers are kept for two more years… what was to prevent the lawmakers from keeping them on for ten more years? With conscription, he warned, “all patriotism is dead, and the Confederacy will be dead sooner or later.” [15]

The act stated that “all persons residing in the Confederate States, between the ages of 18 and 35 years, and rightfully subject to military duty, shall be held to be in the military service of the Confederate States, and that a plain and simple method be adopted for their prompt enrollment and organization.” [16] The one-year volunteers had their service extended to three years or to the duration of the war. The existing regiments had forty days to reorganize under the act and hold elections for their officers, in elections which season politicians in the ranks used time tested methods of campaigning, including the distribution and consumption of copious amounts of alcohol on the day when their regiments elected their officers. A private from Alabama wrote, “Passed the whiskey round & opened the polls… & a great many of the men are gloriously tight.” [17] In some cases the elections meant that good officers were cashiered, and “good fellows” chosen in their places, “but on the whole, the elections wrought less evil than could reasonably be expected.” [18] Even so, the professional core of the Army officers, many West Point graduates, was less than happy, as were some of the best volunteer officers. Brigadier General Wade Hampton, a volunteer who would eventually rise to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia following the death of J.E.B. Stuart in 1864 “disapproved of the balloting for officers, explaining, “The best officers are sometimes left out because they are too strict.” Another South Carolina officer noted; “officers who have discharged their duties properly are not popular with their men and those who have allowed the most privileges have been the least efficient and will be elected.” [19] The elections and reorganization of the Army of Northern Virginia resulted in “the replacement of 155 field officers by newly elected men. The “whole effect,” wrote Porter Alexander, “was prejudicial to the discipline of the army.” [20]

In many cases the turnover in company grade officers was much more dramatic, in some cases fifty to seventy-five percent of officers were replaced in the elections, the “18th North Carolina Infantry replaced twenty-seven of forty officers. According to the new regimental commander, “Many of these officers elect were reported “incompetent” by a Board of Examination.” [21] Officers who failed to be reelected had the choice to remain in their units as enlisted personnel, but comparatively few did, often going to newly raised regiments where they were again commissioned and brought their experience along with them.

The act was highly controversial, often resisted, and “many Southerners resisted the draft or assisted evasion by others” [22] The Confederate Congress issued a large number of class exemptions. The first exemptions were granted to “Confederate and state civil officials, railroad and river workers, telegraph operators, minors, several categories of industrial laborers, hospital personnel, clergymen, apothecaries, and teachers.” [23] The exemptions made sense, “but the categories would see much abuse by those seeking to stay out of uniform.” [24]

Initially the Congress fought off an attempt by planters to grant exemptions to “the owners, agents, or overseers with more than twenty slaves” [25] but a law to this effect was passed in October 1862. The exemption granted by Congress for the “owners or overseers of twenty or more slaves” [26] stirred up a hornet’s nest of resentment across the South. The October law “protected large-scale-slave-owning planters – the very people who had the most stake in this war – from military service, while drafting the small scale slaveowners and nonslaveholders who had the least interest in fighting to defend slavery.” [27] One of Mississippi’s slaveowning senators, James Phelan confidentially advised Davis that “never did a law meet with more universal odium than the exemption of slave-owners…. Its influence on the poor is most calamitous, and has awakened a spirit and elicited a discussion” that would surely produce “the most unfortunate results.” [28]

He was right, though Confederate soldiers would remain in the fight they “turned against what had originally called a crusade for independence. Now it was a “rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight,” the inference being that the wealth classes had provoked the struggle but poor people were the ones who had to fight, bleed, and die.” [29] Lee’s aide, Colonel Charles Marshall who had drafted the original conscription act, said that the “measure’s effect was “very injurious” and “severely commented upon in the army.” [30]

The main effect of the conscription act was “to stimulate volunteering rather than by its actual use” [31] and “directly and indirectly, the Conscription Act from large numbers of men into Lee’s army.” [32] While the act did help increase the number of soldiers in Confederate service by the end of 1862 conscription was decidedly unpopular among soldiers. A Texas soldier whose unit had been reenlisted wrote that the new draft law “kicked up a fuss for a while, but since they shot about twenty-five men for mutiny whipped & shaved the heads of as many more for the same offense everything has got quiet & goes on as usual.” [33]

Conscripts were often looked down upon in the ranks as many of the old soldiers felt that they lacked the patriotism and honor to volunteer in the first place, and many who did show up were of dubious value. Statics from November 1863 indicated that “more than half of those who reported for conscription were ultimately exempted from duty.” [34] While many of these were for medical reasons, others claimed the exemptions provided for in the law.

Some governors who espoused state’s-rights viewpoint “utilized their state forces to challenge Richmond’s centralized authority, hindering efficient manpower mobilization.” [35] Some, most notably Georgia’s governor Joseph Brown “denounced the draft as “a most dangerous usurpation by Congress of the rights of the States…at war with all principles for which Georgia entered the revolution.” [36] Governor Brown and a number of other governors, including Zebulon Vance of North Carolina, did more than protest, they fought the law in the courts but when overruled they resisted it by manipulating the many exemption loopholes, especially, especially those that which they could grant to civil servants. Brown “appointed large numbers of eligible Georgia males to fictitious state offices in order to exempt them,” [37] and Brown “insisted that militia officers were included in this category, and proceeded to appoint hundreds of new officers.” [38] North Carolina and Georgia “accounted for 92 percent of all state officials exempted from the draft” and a “Confederate general sarcastically described a Georgia or North Carolina militia regiment as containing “3 field officers, 4 staff officers, 10 captains, 30 lieutenants, and 1 private with a misery in his bowels.” [39] In South Carolina, “Governor Francis W. Pickens was trying to impose a state draft of his own and attempted to exempt South Carolina draftees from any liability to the Confederate draft.” [40]

Due to the problems with the Conscription Act of 1862 and the abuses by the governors it was amended twice in new bills in late 1862 and again in 1864 when Jefferson Davis lobbied Congress to pass the Conscription Act of 1864. This act was designed to correct problems related to exemptions and “severely limited the number of draft exemption categories and expanded military age limits from eighteen to forty-five and seventeen to fifty. The most significant feature of the new act, however, was the vast prerogatives it gave to the President and War Department to control the South’s labor pool.” [41] Despite these problems the Confederacy eventually “mobilized 75 to 80 percent of its available draft age military population.” [42]

While the act was unpopular, it did hold the army together and without it “the Confederacy could not have survived the 1862 campaigns without the veterans, and compelled the states to produce fresh regiments when their nation needed them.” [43] During 1862 the total number of men in the Confederate army “increased from about 325,000 to 450,000. Since about 75,000 men were lost from death or wounds during this period, the net gain was approximately 200,000. Fewer than half of the men were conscripts and substitutes; the remainder were considered volunteers even if their motives for enlisting many not have been unalloyed with patriotism.” [44] The results of the draft in getting men to combat units were still in evidence in the spring of 1864. “An officer of the 45th Georgia maintained that the regiment had come to Virginia with roughly 1,000 men in April 1862, and fell back from Antietam with only 200 left. At the start of the spring campaign, the regiment listed 425 men on its rolls as present.” [45] Despite all of the flaws and the condemnations the various conscription acts of the Confederacy provided the necessary manpower to continue the war.

Notes

[1] Levine, Bruce The Fall of the House of Dixie: The Civil War and the Social Revolution that Transformed the South Random House, New York 2013 p.83

[2] Ibid. Weigley A Great Civil War p.118

[3] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie p.83

[4] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.429

[5] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.364

[6] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p. 429

[7] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee an abridgment by Richard Harwell, Touchstone Books, New York 1997 p.172

[8] Davis, William C. Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour Harper Collins Publishers New York 1991 p.453

[9] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie p.84

[10] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume One: Fort Sumter to Perryville Random House, New York 1963 1958 p.395

[11] Ibid. Davis Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour p.453

[12] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.430

[13] Ibid. Freeman Lee p.172

[14] Ibid. Weigley A Great Civil War p.118

[15] Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1992 p.52

[16] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.152

[17] Ibid. Sears To the Gates of Richmond+ p.52

[18] Ibid. Freeman Lee pp.172-173

[19] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.85

[20] Wert, Jeffry D. A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2011 p.13

[21] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.86

[22] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.152

[23] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p. 431

[24] Ibid. Davis Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour p.453

[25] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.365

[26] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.154

[27] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.365

[28] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie pp.84-85

[29] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.38

[30] Ibid. Levine The Fall of the House of Dixie p.85

[31] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p. 432

[32] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.402

[33] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.39

[34] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.402

[35] Millet, Allan R. and Maslowski, Peter, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States The Free Press a Division of Macmillan Inc. New York, 1984 p.166

[36] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.433

[37] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.364

[38] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.431

[39] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.431

[40] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.364

[41] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.261

[42] Ibid. Gallagher The Confederate War p.88

[43] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.402

[44] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.432

[45] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.402