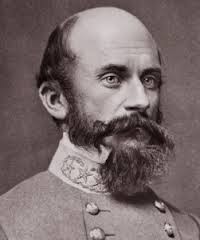

Robert E. Lee 1863

Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

I decided to take this weekend to take some parts of my Gettysburg Staff Ride text to debunk the mythology of the Lost cause that presented Robert E. Lee as one of the greatest, if not the greatest General in American history. I am not the first or the last to do this. Like many people of my generation, almost everything I read about Lee was what a great General and American he was. There was little mention of his active support of slavery, or his sedition and treason against the United States. But that is another story. Tonight we deal with Lee’s incompetence at the tactical and operational levels of war at Gettysburg, his willful ignorance of his own position and what was facing him a little over a mile way.

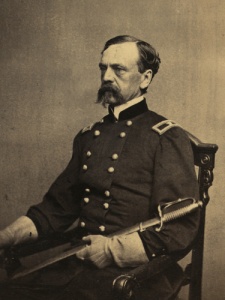

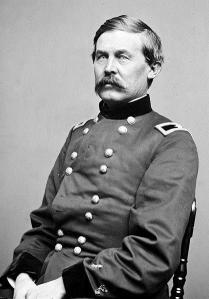

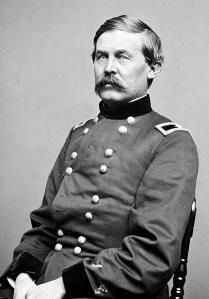

At the same time it juxtaposes Lee’s hubris with the often underrated and dismissed opposing commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General George Meade. Lee’s actions are described in the first section, while Meade’s which in an edited form are a vignette in Army Doctrine Publication 5-0, The Operations Process. Unlike Lee, Meade listened to his staff and sought the counsel of his subordinate commanders. Likewise, where Lee never left his headquarters on Seminary Ridge, observing the battle from a distance on 2 July, Meade was in the thick of the action at numerous threatened throughout the battle. Thus, unlike Lee who knew nothing of the real situation on the battlefield and the condition of his Army, and did not want to know it, Meade knew the situation and then that night sought the counsel of his Corps Commanders and Staff.

This is an important point to note when evaluating the Generalship of Robert E. Lee. In every battle except Fredericksburg and Cold Harbor where he was on the defensive and his army well dug in, he always lost a higher percentage of his troops engaged than his Union counterparts, even when he won. If an Army commander knows that he cannot match the overwhelming numerical and firepower advantage of his opponent he has to do everything that he can to husband his soldiers and not to waste their lives in battles that even if won, would not materially alter the course of the war is either incompetent, negligent, or so arrogant in regards to their abilities, that they cannot be regarded as great commanders. To do so is to propagate a murderous myth.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

Part One: Lee

As night fell on July 2nd 1863 General Robert E Lee had already made his decision. Despite the setbacks of the day he was determined to strike the Army of the Potomac yet again. He did not view the events as setback, and though he lacked clarity of how badly many of his units were mauled Lee took no external counsel, to make his decision, his mind was made up and he neither wanted advice or counsel. By now his subordinate commander’s opinions were irrelevant, and to that end on every day of the Battle of Gettysburg he refused any counsel that did not agree with his vision, which had become myopic and disconnected from the reality faced by his rebellious nation and the Army that he led. After two full days of combat in which his forces failed to break the Union defenses, in which The Army of the Potomac’s commanders out-generaled Lee’s commanders time and time again, and every division he threw at the Union defenses suffered 40% casualties on the first two days, including one division commander mortally wounded and three others wounded. Likewise, numerous brigade and regimental commanders had been killed or wounded.

With the exception of A.P. Hill who came and submitted a report to him at dusk on July 2nd, Lee neither required his other two corps commanders, James Longstreet or Richard Ewell to consult with him, nor took any action to visit them. Lee now lived in a bubble, and his very small staff were nothing more than cyphers, there to transmit orders, not to assist in the planning or coordination of his operations.

Despite the massive casualties and being repulsed all along the line, Lee did “not feel that his troops had been defeated” and he felt that “the failure on the second day had been due to a lack of coordination.”1

In his official report of the battle he wrote:

“The result of this day’s operations induced the belief that, with proper concert of action, and with the increased support that the positions gained on the right would enable the artillery to render to the assaulting columns, that we should succeed, and it was ultimately determined to continue the attack…” 2

While Lee’s charge of a “lack of coordination” of the attacks can certainly be substantiated, the fact of the matter was that if there was anyone to blame for his lack of coordination it was him, and even Lee’s most devoted biographer Douglas Southall Freeman would write that on July 2d “the Army of Northern Virginia was without a commander.” 3 Likewise, Lee’s decision to attack on July 3rd, having not taken counsel of his commanders or assessed the battle-worthiness of the units that he was planning to use his final assault on the Union center was “utterly divorced from reality.” 4 His plan was essentially unchanged from the previous day. Longstreet’s now battered divisions were to renew their assault on the Federal left in coordination with Pickett and two of Hill’s divisions.

In light of Lee’s belief that “a lack of coordination” was responsible for the failures of July 2nd it would have been prudent for him to ensure such coordination happened on the night of July 2nd. “Lee would have done well to have called out his three lieutenants to confer with them and spell out exactly what he wanted. That was not the way he did things however…” 5

Lee knew about the heavy losses among his key leaders but “evidently very little was conveyed to him regarding the condition of the units engaged this day.” 6 This certainly had to be because during the day his only view of the battlefield was from Seminary Ridge through binoculars and because he did not get first hand reports from the commanders involved. Lee was undeterred and according to some who saw Lee that night he seemed confident noting that when Hill reported he shook his and said “It is well, General,…Everything is well.” 7

It was not an opinion that Lee’s subordinates shared. Ewell and his subordinates were told to renew their attack on Cemetery and Culp’s Hill on the night of July 2nd, but “he and his generals believed more than ever that a daylight assault against the ranked guns on Cemetery Hill would be suicidal-Harry Hays said that such an attack would invite “nothing more than slaughter…” 8

James Longstreet was now more settled in his opposition to another such frontal attack and shortly after dawn when Lee visited him to deliver the order to attack again argued for a flanking movement around the Federal left. Lee’s order was for Longstreet to “attack again the next morning” according to the “general plan of July 2nd.” 9 Longstreet had not wanted to attack the previous day and when Lee came to him Longstreet again attempted to persuade Lee of his desire to turn the Federal flank. “General, I have had my scouts out all night, and I find that you still have an excellent opportunity to move around to the right of Meade’s army and maneuver him into attacking us.” 10

Lee would have nothing of it. He looked at his “Old Warhorse” and as he had done the previous day insisted: “The enemy is there,” he said, pointing northeast as he spoke, “and I am going to strike him.” 11 Longstreet’s gloom deepened and he wrote that he felt “it was my duty to express my convictions.” He bluntly told Lee:

“General, I have been a soldier all of my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions and armies, and should know, as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arranged for battle can take that position.” 12

But Lee was determined to force his will on both his subordinates and the battle. Lee was convinced that the plan could succeed while Longstreet “was certain” that the plan “was misguided and doomed to fail.” 13 Longstreet, now realized that further arguments were in vain recalled that Lee “was impatient of listening, and tired of talking, and nothing was left but to proceed.” 14

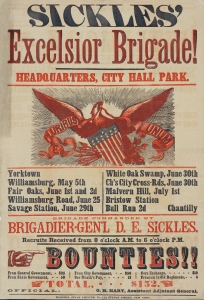

Even a consultation with Brigadier General William Wofford whose brigade had help crush Sickle’s III Corps at the Peach Orchard and had nearly gotten to the crest of Cemetery Ridge could not alter Lee’s plan. Wofford had to break off his attack on July 2nd when he realized that there were no units to support him. Lee asked if Wofford could “go there again” to which Wofford replied “No, General I think not.” Lee asked “why not” and Wofford explained: “General, the enemy have had all night to intrench and reinforce. I had been pursuing a broken enemy, and now the situation is very different.” 15

The attack would go forward despite Longstreet’s objections and the often unspoken concerns of others who had the ear of Lee, or who would carry out the attack. Walter Taylor of Lee’s staff wrote to his sister a few days after the attack the “position was impregnable to any such force as ours” while Pickett’s brigadier Richard Garnett remarked “this is a desperate thing to attempt” and Lewis Armistead said “the slaughter will be terrible.” 16

Pickett’s fresh division would lead the attack supported by Johnston Pettigrew commanding the wounded Harry Heth’s division of Hill’s Third Corps and Isaac Trimble commanding two brigades of Pender’s division, Trimble having been given command just minutes prior to the artillery bombardment. 17 On the command side few of the commanders had commanded alongside each other before July 3rd. Trimble had just recovered from wounds had never been with his men. Pettigrew had been given command when Pender was wounded was still new and relatively untested, and Pickett’s three brigadiers and their brigades had never fought together. Two of the divisions had never served under Longstreet. From a command perspective where relationships and trust count as much as strength and numbers the situation was nearly as bad is it could be. Although the Confederates massed close to 170 cannon on Seminary Ridge to support the attack ammunition was in short supply and the Lieutenant Colonel Porter Alexander who had been tasked with coordinating fires only controlled the guns of First Corps.

The assaulting troops would attack with their right flank exposed to deadly enfilade fire from Federal artillery and with the left flank unsupported and exposed to such fires from Union artillery on Cemetery Hill. It was a disaster waiting to happen. Longstreet noted “Never was I so depressed as on that day…” 18

Part Two: Meade

While Lee took no counsel and determined to attack on the night of July 2nd little more than two miles away Major General George Meade took no chances. After sending a message to Henry Halleck at 8 PM Meade called his generals together. Unlike Lee who had observed the battle from a distance Meade had been everywhere on the battlefield during the day and had a good idea what his army had suffered and the damage that he had inflicted on the Army of Northern Virginia. Likewise during the day he had been with the majority of his commanders as opposed to Lee who after issuing orders that morning had remained unengaged, as was noted by the British observer Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle who wrote that during the “whole time the firing continued, he sent only one message, and only received one report.” 19

Meade wired Halleck that evening: “The enemy attacked me about 4 P.M. this day…and after one of the severest contests of the war was repulsed at all points.” 20 However Meade, realizing that caution was not a vice still needed to better assess the condition of his army, hear his commanders and hear from his intelligence service, ended his message: “I shall remain in my present position to-morrow, but am not prepared to say until better advised of the condition of the army, whether operations will be of an offensive or a defensive character.” 21

As Meade waited for his commanders his caution was apparent. Before the attack on Sickles’ III Corps at the Peach Orchard Meade had asked his Chief of Staff Brigadier General Dan Butterfield to “draw up a contingency plan for withdraw to Pipe Creek.” After the attack on Sickles Alfred Pleasanton said that Meade ordered him to “gather what cavalry I could, and prepare for the retreat of the army.” 22 Some of his commanders who heard of the contingency plan including John Gibbon and John Sedgwick believed that Meade was “thinking of a retreat.” 23. Despite Meade’s flat assurances to Halleck his army’s position had been threatened on both flanks, though both were now solidly held, but some of his subordinates believed, maybe through the transference of their own doubts, that Meade “foresaw disaster, and not without cause.” 24

In assessing Meade’s conduct it has to be concluded that while he had determined to remain, that he was smart enough to plan of the worst and to consult his commanders and staff in making his decision. Meade wrote to his wife that evening “for at one time things looked a little blue,…but I managed to get up reinforcements in time to save the day….The most difficult part of my work is acting without correct information on which to predicate action.” 25

Meade called Colonel George Sharpe from the Bureau of Military Information to meet with him, Hancock and Slocum at the cottage on the Taneytown Road where he made his headquarters. Sharpe and his aide explained the enemy situation. Sharpe noted “nearly 100 Confederate regiments in action Wednesday and Thursday” and that “not one of those regiments belonged to Pickett.” He then reported with confidence that indicated that “Pickett’s division has just come up and is bivouac.” 26

It was the assurance that Meade needed as his commanders came together. When Sharpe concluded his report Hancock exclaimed “General, we have got them nicked.” 27

About 9 P.M. the generals gathered. Present were Meade, and two of his major staff officers Warren just back from Little Round Top, wounded and tired, and Butterfield his Chief of Staff. Hancock action as a Wing Commander was there with Gibbon now commanding II Corps, Slocum of XII Corps with Williams. John Newton a division commander from VI Corps who had just arrived on the battlefield now commanding I Corps was present along with Oliver Howard of XI Corps, John Sedgwick of VI Corps, George Sykes of V Corps and David Birney, now commanding what was left of the wounded Dan Sickles’ III Corps. Pleasanton was off with the cavalry and Hunt attending to the artillery.

The meeting began and John Gibbon noted that it “was at first very informal and in the shape of a conversation….” 28 The condition of the army was discussed and it was believed that now only about 58,000 troops were available to fight. Birney honestly described the condition of III Corps noting that “his corps was badly chewed up, and that he doubted that it was fit for much more.” 29 Newton who had just arrived was quoted by Gibbon as saying that Gettysburg was “a bad position” and that “Cemetery Hill was no place to fight a battle in.” 20 The remarks sparked a serious discussion with Meade asking the assembled generals “whether our army should remain on that field and continue the battle, or whether we should change to some other position.” 31

The reactions to the question showed that the army commanders still had plenty of fight in the. Meade listened as his generals discussed the matter. Hancock said he was “puzzled about the practicability of retiring.” 32 Newton later noted that he made his observations about the battlefield based on his belief that that Lee might turn the Federal left and impose his army between it and its supplies, as Longstreet However Newton and the other commanders agreed that pulling back “would be a highly dangerous maneuver to attempt in the immediate presence of the enemy.” 33

Finally Butterfield, no friend of Meade and one of the McClellan and Hooker political cabal who Meade had retained when he took command posed three questions to the assembled generals:

“Under existing circumstances, is it advisable for this army to remain in its present position, or retire to another nearer its base of supplies?

It being determined to remain in present position, shall the army attack or wait the attack of the enemy?

If we wait attack, how long?” 34

Gibbon as the junior officer present said “Correct the position of the army…but do not retreat.” Williams counseled “stay,” as did Birney and Sykes, and Newton, who after briefly arguing the dangers finally agreed. Oliver Howard not only recommended remaining but “even urged an attack if the Confederates stayed their hand.” Hancock who earlier voiced his opinion to Meade that “we have them nicked” added “with a touch of anger, “Let us have no more retreats. The Army of the Potomac has had too many retreats….Let this be our last retreat.” Sedgwick of VI Corps voted “remain” and finally Slocum uttered just three words “stay and fight.” 35

None of Meade’s assembled commanders counseled an immediate attack; all recommended remaining at least another day. When the discussion concluded Meade told his generals “Well gentlemen…the question is settled. We remain here.”36

Some present believed that Meade was looking for a way to retreat to a stronger position, that he had been rattled by the events of the day. Slocum believed that “but for the decision of his corps commanders” that Meade and the Army of the Potomac “would have been in full retreat…on the third of July.” 37 Meade would deny such accusations before Congressional committees the following year as Radical Republicans in Congress sought to have him relieved for political reasons.

Much of the criticism of his command decisions during the battle were made by political partisans associated with the military cabal of Hooker, Butterfield and Sickles as well as Radical Republicans who believed that Meade was a Copperhead. Both Butterfield and Birney accused Meade before the committee of wanting to retreat and “put the worst possible interpretation on Meade’s assumed lack of self-confidence without offering any real evidence to substantiate it.”Edwin Coddington notes “that Meade, other than contemplating a slight withdraw to straighten his lines, wanted no retreat from Gettysburg.” 38

Alpheus Williams of XII Corps, wrote to his daughters on July 6th regarding his beliefs about Meade on the night of July 2nd. “I heard no expression from him which led me to think that he was in favor of withdrawing the army from before Gettysburg.” 39 Likewise the message sent by Meade to Halleck indicates Meade’s own confidence in the upcoming battle of July 3rd. If Meade had some reservations during the day, as he mentioned in the letter to his wife they certainly were gone by the time he received the intelligence report from Sharpe and heard Hancock’s bold assertion that the enemy was “nicked.”

As the meeting broke up after shortly after midnight and the generals returned to their commands Meade pulled Gibbon aside. Gibbon with II Corps had the Federal center on Cemetery Ridge. Meade told him “If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be in your front.” Gibbon queried as to why Meade thought this and Meade continued “Because he has made attacks on both our flanks and failed,…and if he concludes to try it again it will be on our center.” Gibbon wrote years later “I expressed the hope that he would, and told General Meade with confidence, that if he did we would defeat him.” 40

If some of his generals and political opponents believed Meade to be a defeatist, that defeatism was not present in his private correspondence. He wrote to his wife early in the morning of July 3rd displaying a private confidence that speaks volumes: “Dearest love, All well and going on well in the Army. We had a great fight yesterday, the enemy attacking & we completely repulsing them- both armies shattered….Army in fine spirits & every one determined to do or die.” 41

The contrast between Lee’s and Meade’s decision making process is Meade did what Lee should have done, he had been active on the battlefield, he consulted his intelligence service and he consulted his commanders on the options available to him. Lee remained away from the action on July 2nd he failed to consult his commanders. He failed to gain accurate intelligence on the Federal forces facing him and he failed to fully take into account his losses. Meade better demonstrated the principles of what we now call “mission command.”

Notes

1 Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.558

2 Lee, Robert E, Reports of Robert E Lee, C.S. Army, Commanding Army of Northern Virginia Campaign Report Dated January 20th 1864. Amazon Kindle Edition location 594 of 743

3 Freeman, Douglas S. R.E. Lee volume 3 Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1935 p.150

4 Sears, Stephen W Gettysburg Houghton Mifflin Company, New York 2003 p.349

5 Coddinton, Edwin Gettysburg, A Study in Command Simon and Schuster New York 1968 p.455

6 Trudeau, Noah Andre Gettysburg, A Testing of Courage Harper Collins, New York 2002 p.4117 Ibid p.412

8 Ibid. p.347

9 Ibid. p.430

10 Wert, Jeffry General James Longstreet, the Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier A Tuchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York 1993 p.283

11 Foote, Shelby The Civil War, A Narrative, Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.529 12 Ibid. Wert p.283

13 Ibid. Sears p.349

14 Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.377

15 Ibid. Foote p.531

16 Ibid. Wert p.287

17 Ibid. Freeman p.589

18 Ibid. Wert p.290

19 Fremantle, Arthur Three Months in the Southern States, April- June 1863 William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London 1863 Amazon Kindle edition p.266

20 Sears, Stephen W Gettysburg Houghton Mifflin Company, New York 2003 pp.341-342

21 Ibid. p.342

22 Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.355

23 Ibid.

24 Foote, Shelby The Civil War, A Narrative, Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.524

25 Trudeau, Noah Andre Gettysburg, A Testing of Courage Harper Collins, New York 2002 p.413

26 Ibid. Sears p.342

27 Ibid. Trudeau p.413

28 Ibid. Sears p.342

29 Ibid. Trudeau p.415

30 Ibid. Guelzo p.556

31 Ibid. Guelzo p.556

32 Ibid. Sears p.343

33 Ibid. Sears p.343

34 Ibid. Trudeau p.415

35 Ibid. Guelzo p.556

36 Ibid. Foote p.525

37 Ibid. Guelzo

38 Coddinton, Edwin Gettysburg, A Study in Command Simon and Schuster New York 1968 pp.451-452

39 Ibid. p.452

40 Ibid. Foote p.525

41 Ibid. Trudeau p.345

Share this:

Loading…

Related

From Strategic Incompetence to Negligence in Conducting a do or Die Offensive: Robert E. Lee’s Lazy and Disastrous Discretionary Orders at Gettysburg, 1 July 1863July 2, 2022In “civil war”

What a Long Strange Trip it’s Been: This Navy Chaplain’s Work Becomes Part of an Army Operational ManualAugust 19, 2018In “civil war”

The Night that Ended the Myth of Robert E. Lee’s “Superior Generalship” George Meade and His Conference of War at GettysburgJuly 14, 2020In “civil war”

Filed under civil war, History, leadership, Military

Tagged as a.p. hill, alpheus williams, battle of gettysburg, colonel george sharpe, daniel butterfield, david birney, douglas southall freeman, george meade, george pickett, george sykes, henry halleck, henry slocum, james longstreet, john gibbon, john newton, john sedgwick, mission command, oliver howard, richard ewell, robert e lee, william wofford, winfield scott hancock

Leave a Reply

Advertisements

blob:https://padresteve.wordpress.com/d144114d-70d5-46af-a56a-1fadbff5f042

REPORT THIS AD

- Welcome!

- Subscribe to Padre Steve’s WorldEnter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.Join 6,785 other followersEmail Address:Sign me up!

- Comment PolicyFriends of Padre Steve’s World I welcome comments, even those which disagree with my positions and articles. I have done this for years, but recently I have been worn out by some people. I have just a couple of rules for comments. First, be respectful of me and other commentators. If you are polite and respectful’ even if I disagree with you your comment will be posted and I will respond accordingly. That being said I will not allow people to hijack the comment section to push their religious or ideological views. Unless the comment deals with the meat of the article, don’t expect me to allow you to preach, especially if you are a racist, anti-Semetic, or are a homophobe. Nor will I allow spam comments. Most of those are automatically blocked by WordPress but some do get through, and deal with them accordingly. Peace Padre Steve+

- https://www.facebook.com/v2.3/plugins/page.php?app_id=249643311490&channel=https%3A%2F%2Fstaticxx.facebook.com%2Fx%2Fconnect%2Fxd_arbiter%2F%3Fversion%3D46%23cb%3Df19bd90c7e6019c%26domain%3Dpadresteve.com%26is_canvas%3Dfalse%26origin%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fpadresteve.com%252Ff3eeaf8e99127c%26relation%3Dparent.parent&container_width=230&height=130&hide_cover=false&hide_cta=false&href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fpages%2FPadre-Steves-WorldMusings-of-a-Passionate-Moderate%2F105948589438169&locale=en_US&sdk=joey&show_facepile=true&small_header=false&tabs=false&width=200

- What’s Hot

- The Unexplained and Tragic Death of David Wilkerson

- The Less than Stellar Planning Ability of the Mythological General Robert E. Lee

- Gettysburg Day One: Lee’s Vague Discretionary Orders and Lack of Control

- “God himself could not sink this ship.” The Titanic, Bruce Ismay and Trump

- Welcome!

- From Strategic Incompetence to Negligence in Conducting a do or Die Offensive: Robert E. Lee’s Lazy and Disastrous Discretionary Orders at Gettysburg, 1 July 1863

- “If not us, then who? If not now, then when?” Remembering Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech

- I’ve Got those Yellowstain Blues: Watching as the President Snatches Defeat from Victory and Sends the Middle East into a Major Conflict

- Double Dog Damned: “‘I’m the f-ing president. Take me up to the Capitol now,’”

- “Revisionist” History and the Rape of Nanking 1937

- Search for:

- Padre Steve’s Inglorius Statistics

- 8,056,336 Inglorius Readers

- Recent Articles

- From Strategic Incompetence to Negligence in Conducting a do or Die Offensive: Robert E. Lee’s Lazy and Disastrous Discretionary Orders at Gettysburg, 1 July 1863

- The Less than Stellar Planning Ability of the Mythological General Robert E. Lee

- Double Dog Damned: “‘I’m the f-ing president. Take me up to the Capitol now,’”

- Christian Nationalism, Judicial Activism, and the Looming Threat to the Republic

- The Murderous Heart and Intent of Trump’s Christian Nationalist Subjects

- The Vault: Padre Steve’s Archives

- July 2022

- June 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- November 2014MTWTFSS 123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930« Oct Dec »

- Categories

- afghanistan

- aircraft

- alternative history

- alzheimer’s disease

- anti-semitism

- armored fighting vehicles

- artillery

- authoritarian government

- Baseball

- baseball

- basketball

- Batlimore Orioles

- beer

- books

- books and literature

- celebrities

- christian life

- civil rights

- civil war

- civil war

- Climate

- Climate change,

- Coronavirus

- Coronavirus 19 Pandemic

- counterinsurency in afghanistan

- COVID19

- crime

- crimes against humanity

- culture

- dachshunds

- Diseases Epidemics and Pandemics

- dogs

- ecology and energy

- economics and financial policy

- enteratinment

- ER’s and Trauma

- ethics

- euthanasia

- faith

- film

- football

- Foreign Policy

- germany

- Gettysburg

- golf

- hampton roads and tidewater

- healthcare

- historic preservation

- History

- history

- holocaust

- Immigration and immigrants

- impeachment

- Impeachment Trials

- imperial japan

- iraq

- iraq,afghanistan

- Just for fun

- Korean Conflicts

- labor

- laws and legislation

- leadership

- LGBT issues

- Lies of World Net Daily

- life

- Loose thoughts and musings

- marriage and relationships

- mental health

- middle east

- Military

- ministry

- movies

- music

- My Other Blogs

- national security

- natural disasters

- Navy Ships

- nazi germany

- News and current events

- norfolk tides

- nuclear weapons

- papillons

- Pastoral Care

- philosophy

- Photo Montages

- Political Commentary

- political commentary

- pro-life anti-abortion

- PTSD

- purely humorous

- racism

- Religion

- remembering friends

- russia

- satire

- School stories

- shipmates and veterans

- slavery

- Sleep and Insomnia

- soccer

- spirituality

- sports and life

- star trek

- state government agencies

- suicide

- Teaching and education

- televsion

- terrorism

- the blacklist

- things I don’t get

- to iraq and back

- Tour in Iraq

- traumatic national events

- travel

- Travel

- ukraine

- Uncategorized

- us air force

- us army

- US Army Air Corps

- US Marine Corps

- US Navy

- US Presidents

- Veterans and friends

- vietnam

- war crimes

- war crimes trials

- War on Terrorism

- weather

- west virginia

- White nationalism

- winter olympics

- women’s rights

- World War II at Sea

- world war one

- world war two in europe

- world war two in the pacific

- Blogs I Follow

- Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory!

- It Is What It Is

- Questionable Motives

- Square Cop In A Round World

- Discover WordPress

- Another Spectrum

- Chicago FEEDBACK Film Festival

- Mar3sons

- RelaxMaven

- Seclusion 101 with AnneMarie

- DogsRealty.com

- New Dog New Tricks

- WJB’s Turn

- John Oliver Mason

- Mrmoteeye’s Blog

- Consolation of Antiquity

- NONVIOLENT CHRISTIANS

- Filosofa’s Word

- SeanMunger.com – Official Site of Speaker, Historian and Author Sean Munger

- Souvenirs de guerre