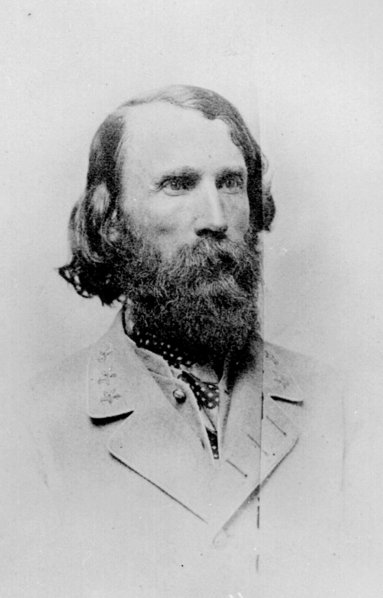

While A.P. Hill and Harry Heth ignored warnings and launched their troops towards Gettysburg, Buford believing an engagement was in the offing sought out good ground to give battle and hold back the enemy until the army could arrive. This he found on the ridges west of Gettysburg. The choice of ground is always important and in this battle was paramount to the success of the Army of the Potomac. Buford alerted Major General John Reynolds and the cavalry corps commander Alfred Pleasanton to the location of the approaching Confederates on the night of June 30th. However, Buford’s warning, and that of the intelligence bureau came too late for Reynolds or Meade to take action on them that evening, nor give Meade “to dictate the choice of giving or accepting battle.” [1]

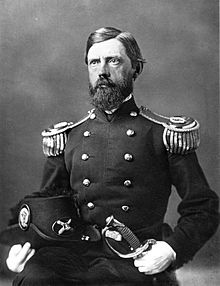

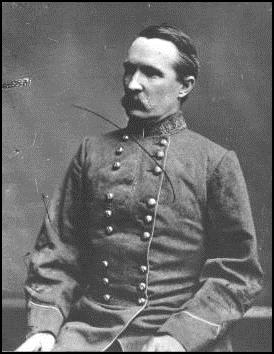

The Army of the Potomac had the good fortune of having Reynolds in this key position on the morning of July 1st 1863. John Reynolds was one of the finest commanders on either side during the Civil War. He graduated from West Point in 1841 and served in the artillery. He fought during the war with Mexico serving in Braxton Bragg’s battery winning fame and two brevet promotions for bravery, [2] to Captain at Monterrey and Major at Buena Vista. Following the war he remained in the army. He served in field and coastal batteries and like John Buford had “participated in the Utah Expedition.” [3] In 1860 he was appointed as Commandant of the Corps of Cadets at West Point and served there until June of 1861 when he was appointed as Lieutenant Colonel of the 14th U.S. Infantry regiment. [4]

However, he was soon promoted to Brigadier General and he commanded a brigade of Pennsylvania volunteers during the Peninsula Campaign. He was captured on June 28th as McClellan began his withdraw from the gates of Richmond but was released in a prisoner exchange on August 15th 1862. [5] He returned to command a division at Second Bull Run where his division held firm as much of the army retreated, but missed the battle of Antietam as he was called to “the fruitless and frustrating task of trying to organize Pennsylvania’s militia” [6] by Governor Curtain. He commanded I Corps at Fredericksburg and again at Chancellorsville and was reportedly offered command of the Army of the Potomac by Lincoln, something that he recounted to his artillery chief Colonel Wainwright that he “refused it because he would have been under the same constraints as Burnside and Hooker.” [7]

The Army of the Potomac’s senior leadership had been the source of much political consternation during 1862 and 1863 for Abraham Lincoln. It was split among Lincoln’s supporters and detractors, Radical Republican abolitionists and moderate Democrats some of its leaders including McClellan, Hooker and Sickles had their own aspirations for the presidency. However, Reynolds was of a different character than some of his fellow commanders. He was a moderate Pennsylvania Democrat and no supporter of Lincoln, once comparing him to a “baboon.” But he “was also a serious unbending professional, who unlike McClellan, actually lived by the principle of “obedience to the powers that be.” [8] “Universally respected” in the army “for his high character and sterling generalship” [9] it was noted that unlike others Reynolds had a policy of holding back “stoutly aloof from all personal or partisan quarrels, and keeping guardedly free from any of the heart-burnings and jealousies that did so much to cripple the usefulness and endanger the reputation of many gallant officers.” [10]

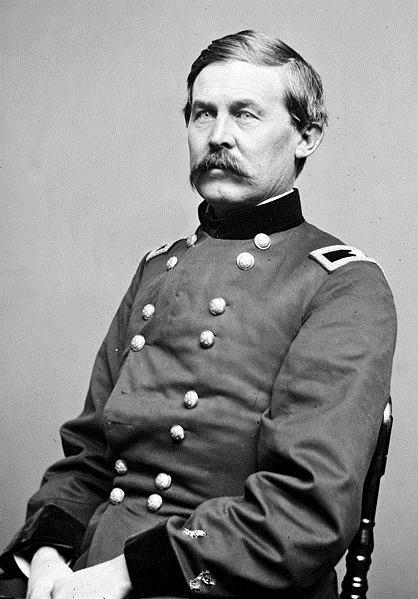

On the night of June 30th Reynolds was awash in reports, some of them conflicting and without Meade’s course of action for the next day “concluded that Lee’s army was close by and in force.” [11] He spent the night at his headquarters “studying the military situation with Howard and keeping in touch with army headquarters.” [12] Howard noted Reynolds anxiety and “Howard received the impression that Reynolds was depressed.” [13] After Howard’s departure Reynolds took the opportunity to get a few hours of fitful sleet before arising again at 4 a.m. on July 1st.

When morning came, Reynolds was awakened by his aide Major William Riddle with Meade’s order to “advance the First and Eleventh Corps to Gettysburg.” [14] Reynolds studied the order and though he expected no battle that morning, expecting “only moving up to be in supporting distance to Buford” [15] took the reasonable precautions that Confederate commanders had not done.

Though Reynolds was not expecting a fight he organized his march in a manner that ensured if one did happen that he was fully prepared. They were precautionary measures that any prudent commander knowing that strong enemy forces were nearby would take. Reynolds certainly took to heart the words of Napoleon who said “A General should say to himself many times a day: If the hostile army were to make its appearance in front, on my right, or on my left, what should I do?” [16] It was a question that A.P. Hill and Harry Heth seemed not to consider on that warm and muggy July morning, where Heth was committing Lee’s army to battle on his own authority, Reynolds was about to do the same, but unlike Heth, he “had at least been delegated the authority for making such a decision.” [17]

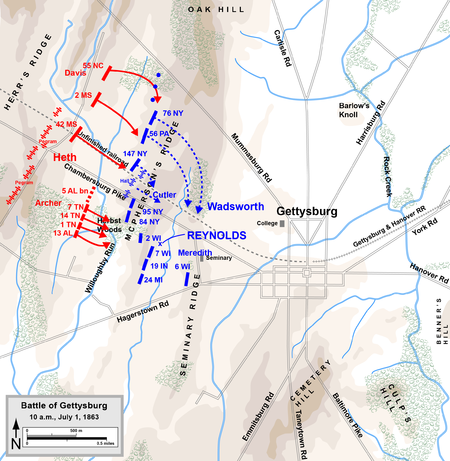

Reynolds “wanted all the fighting troops to be up front, so he instructed Howard not to intermingle his supply wagons with his infantry. Similar instructions had been given to Abner Doubleday; to ensure that the First Corps wagons would wait until the Eleventh Corps foot soldiers had passed.” [18] Likewise, instead operating in the normal fashion of rotating units on the march, Reynolds opted to save time. Since the First Division under the command of James Wadsworth was further advanced than other I Corps divisions, Reynolds instructed it to move first. In doing so he countermanded the order of the acting corps commander Doubleday telling Wadsworth that Doubleday’s order “was a mistake and that I should move on directly.” [19] He went forward with Wadsworth’s division and ordered Doubleday to “assemble the artillery and the remainder of the corps, and join him as soon as possible.” [20] He ordered Howard’s XI Corps to follow and Sickles’ III Corps to come up through Emmitsburg. [21] Reynolds’ intention according to Doubleday was “to fight the enemy as soon as I could meet him.” [22]

Reynolds rode forward with some of his staff into the town as the infantry of I Corps and XI Corps moved advanced. In the town they were met by “a fleeing, badly frightened civilian, who gasped out the news that the cavalry was in a fight.” [23] When he came to the Lutheran Seminary he came across Buford. It was a defining moment of the Civil War, a moment that shaped the battle to come. It has been recounted many times and immortalized on screen in the movie Gettysburg, a time “when the entire battle would come down to a matter of minutes getting one place to another.” [24]

When Buford saw Reynolds infantry advancing he remarked “now we can hold this place.” [25] Reynolds greeted Buford, who was in the cupola of the seminary calling out “What’s the matter John?” to which Buford replied “The devil’s to pay” before coming down to discuss the matter with Reynolds. [26] Buford explained the situation noting that “I have come upon some regiments of infantry…they are in the woods…and I am unable to dislodge them.” [27]

Reynolds needed no other convincing. He asked Buford if he could hold and quickly sent off a number of messages. One officer wrote: “The Genl ordered Genl Buford to hold the enemy in check as long as possible, to keep them from getting into town and at the same time sent orders to Genl Sickles…& Genl Howard to come as fast as possible.” [28] He also sent a message to Meade stating: “The enemy are advancing in strong force. I [Reynolds] fear they will get to the heights beyond the own before I can. I will fight them inch by inch, and if driven into the town, I will barricade the streets and hold them back as long as possible.” [29] He directed Major Weld to take it to Meade with all haste “with the greatest speed I could, no matter if I killed my horse.” [30]

After dictating his instructions Reynolds then did what no senior Confederate commander did, he rode back and took personal charge of the movements of his troops to hurry them forward. Unlike Heth, he had taken note of the ground and recognized from Buford’s reports that “the Confederates were marching only on that single road and thus would not be able to push their forces to the front any faster than Reynolds could reach the battlefield with his First Corps divisions.” [31]

Reynolds, recognizing that time was of the essence if his forces were to hold the ground west of the town selected a shortcut around the town for I Corps. Those forces were directed across the fields near the Condori farm toward the back side of Seminary Ridge, with Reynolds’ staff helping to remove fences to speed the advance. [32] It was not an easy advance as the troops had to move across the farm fields at an oblique and have to “double-quick for a mile and a quarter in the thick humidity just to reach the seminary.” [33]

As troops arrived Reynolds directed them into position. He directed the artillery of Captain James Hall’s 2nd Maine Battery to McPherson’s Ridge instructing Hall “I desire you to damage their artillery to the greatest possible extent, and to keep their fire from our infantry until they are deployed….” [34] The leading infantry of I Corps was James Wadsworth’s understrength division containing just two brigades, its losses from Chancellorsville not being made good and as the result of the loss of regiments discharged because their enlistments had expired.

However these units were “good ones,” composed of hardened combat veterans. Brigadier General Zylander Cutler led his brigade of New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians up first followed by the six foot seven inch tall Quaker, Brigadier General Solomon Meredith’s “Iron Brigade” of westerners following in their distinctive black hats. Reynolds directed Cutler’s brigade north of the Cashtown Pike and “called the Iron Brigade into action on the south side” [35] Reynolds directed Wadsworth to take change on the north side of the road while he looked after the left. [36] It is also believed by some writers that he directed Oliver Howard to prepare Cemetery Hill as a fallback position [37] however; there is more evidence that points to Howard selecting the site himself. [38]

Cutler’s brigade moved north and engaged Davis’ men near the railroad cut, with Davis’ troops initially having the upper hand, inflicting massive casualties Cutler’s regiments. But in a fierce engagement Cutler’s men pushed the unsupported Confederates back into the Railroad Cut where they slaughtered many of those unfortunate soldiers, taking over 200 prisoners and a battle flag. [39]

The Iron Brigade, brought forward by Doubleday hit Archer’s brigade in the front at Herbst Woods on McPherson’s Ridge. As the unit went into action Doubleday “urged the men…to hold it all hazards.” He recalled that the troops, “full of enthusiasm and the memory of their past achievements they said to me proudly, “If we can’t hold it, where will you find men who can?” The effect was dramatic as the Iron Brigade overwhelmed that unit, whose soldiers now realized they were facing “the first team.” Members of the Iron Brigade recalling the voices of Confederate soldiers exclaiming “Here are those damned black-hat fellers again…’Taint no militia-that’s the Army of the Potomac.” [40] As they attempted to withdraw they piled up at a fence near Willoughby Run and were hit in the flank by “a Michigan regiment that had worked its way around through the woods to the south.” [41]

Coddington writes “It was a bad moment for the Army of Northern Virginia, and Archer gained the unenviable distinction of being the first of its general officers to be captured after Lee took command.” [42] As the 2nd Wisconsin advanced into the woods Reynolds urged them forward: “Forward men, for God’s sake and drive those fellows out of those woods….” [43] As he looked around toward the seminary to see the progress of reinforcements Reynolds was struck in the back of the neck by a bullet and fell dead with Doubleday taking command of the First Corps to the west of the town.

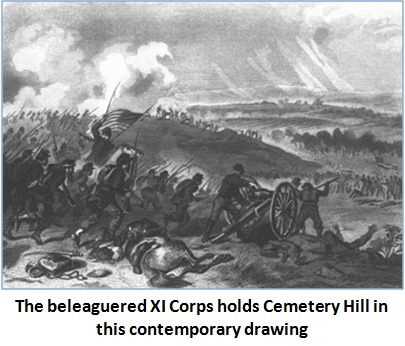

Reynolds was dead, but the series of command decisions reached by Reynolds under the pressure of a meeting engagement “where neither side held an immediate advantage” [44] were critical to the army. Though shaken by his loss the Union troops fought on at McPherson and Seminary Ridge until the assault of Ewell on their left and the arrival of Pender’s fresh division forced them from their positions.

The contrast between Reynolds and his opponents was marked. Hill was ten miles away from the action, Heth too far to the rear of his troops to direct their advance when they ran into trouble. However, Reynolds “hurried to the front, where he was able to inspirit the defense and throw troops into the decisive zone.” [45] At every point John Reynolds showed himself superior to his opponents as he directed the battle and reacted to circumstances. He paid with his life but his sacrifice was not in vain. Harry Hunt noted: “…by his promptitude and gallantry he had determined the decisive field of the war, and he opened brilliantly a battle which required three days of hard fighting to close with a victory.” [46]

Notes

[1] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p. 159

[2] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001pp.47-48

[3] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[4] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[5] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume One Fort Sumter to Perryville Random House, New York 1958 p.493

[6] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[7] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 40-42

[8] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 pp.29-30

[9] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 34

[10] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.30

[11] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[12] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.261

[13] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.48

[14] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.261

[15] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 158

[16] Napoleon Bonaparte, Military Maxims of Napoleon in Roots of Strategy: The Five Greatest Military Classics of All Time edited by Phillips, Thomas R Stackpole Books Mechanicsburg PA 1985 p.410

[17] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 165

[18] Tredeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.159

[19] Ibid. Tredeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.156

[20] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.142

[21] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 158

[22] Ibid. Tredeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.156

[23] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 165

[24] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.142

[25] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.142

[26] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 172

[27] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.143

[28] Ibid. Tredeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.172-173

[29] Schultz, Duane The Most Glorious Fourth: Vicksburg and Gettysburg July 4th 1863. W.W. Norton and Company New York and London, 2002 p.202

[30] Ibid. Tredeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.173

[31] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 166

[32] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.75

[33] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.145

[34] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 pp.28-29

[35] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.271

[36] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day pp.75-76

[37] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.76

[38] Green, A. Wilson. From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p. 70

[39] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.153

[40] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.273

[41] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 pp.470-471

[42] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.271

[43] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.271

[44] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg. p. 168

[45] Krick, Robert K. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day of Gettysburg in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.113

[46] Hunt, Henry. The First Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts. Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ