The Spartacus League brought armed mobs onto the streets of the new and fragile Weimar Republic

The Spartacus League brought armed mobs onto the streets of the new and fragile Weimar Republic

In light of the increasing revolutionary rhetoric from both the political right and left, the ongoing demonstrations in many American cities that are part of the Occupy Wall Street Campaign I felt that it was important to remind people of what can happen when a society enters a revolutionary period. When a nation is in turmoil and is besought by political division and ineffective and out of touch government, a massive economic problems, wars that are believed to be lost and veterans that feel abandoned by their government and isolated from their fellow citizens and what some see as massive economic inequities, or lack of respect for their political, social or religious views then it is facing real danger. It is my belief that we need as individuals and as a nation take a step back from the brink.

Peace, Padre Steve+

The German Revolution of 1919 and civil war is important for those who study highly developed states when they enter a period of social and political upheaval. Often such upheavals occur following military defeats or economic crisis that cause the society to question or even overthrow the established order. The end of Imperial Germany and the establishment of the WeimarRepublicon November 9th 1918 is a prime example. Following the declaration of the Republic the Majority Socialists who had assumed power had no military force of any caliber to support it. The Army had melted away following the end of the war and the units which remained were unreliable and heavily infiltrated by Soviet style “workers and soldiers councils.”

Chaos ruled the streets, Communists and Independent Socialists of The situation being chaotic the Majority Socialists under the leadership of Friedrich Ebert joined forces with German General Staff to create a military force capable of bringing order the Germany. To do this they allowed for the formation of Freikorps to quell revolutionary chaos and avert the establishment of a Soviet State.

The study begins with the establishment of the Republic and concludes with the Kapp Putsch. This is an era that is seldom referenced by political or military leaders in western states and historians themselves are often divided in their interpretation of the subject. The study of this period is vital to those who study politically polarized societies which are either war weary or have suffered the shock of military defeat coupled with a government which is blamed for the events. Thus, it is important to study the relationship of the military to the government and in particular the military’s relationship to politicians who have little connection to or affinity for the military, its traditions and culture and the often adversarial relationship of these politicians to military leadership which often sees them as adversaries. The period also shows how actions of those who in their antipathy to the military create a climate where the military loathes the civilian leadership and the government. The results of such conditions can endanger the society as a whole and ultimately usher in periods of great tragedy. This occurred inWeimarGermanywith the result that the military in the later years of the Republic neither the military nor the Majority Socialists could not work together against the Nazi takeover of the state. However, the first years of the relationship set the tone and foredoomed the Republic.

Freikorps troops battle Leftists in the streets

Freikorps troops battle Leftists in the streets

The history of Weimar, particularly that of the military and Freikorps in their relationship to the Republic is complex. Not only is the relationship between the military and government complex, but the Freikorps themselves, their organization, leadership and political affiliation were not monolithic as is sometimes maintained,[i] nor were the Freikorps the direct ancestors of the Nazi SS/SA organizations despite often similar ideology,[ii] nor can they dismissed by saying that they were composed of “former soldiers and officers ill-disposed to return to civilian life.”[iii] The Freikorps’ association with the Army and Republic is more complex than some historians assert. Despite the right wing leanings of many of units and fighters and future association of some to the Nazis, the blanket claim that the Freikorps were forerunners of the Nazi movement is not supportable.[iv] It is true that without Freikorps support in Munich, along with support of the Thule Society, business leaders and others “that the transition of the DAP into the Hitler party could not have taken place.”[v] It is also true that elements of the Freikorps branded too revolutionary and unruly for service in the Army continued as secret societies and affiliated themselves with various right-wing political groups.[vi] Likewise a case can be made that the fierceness of many Freikorps veterans, younger leaders of the Army laid the foundation for the brutality of both the Army and Waffen SS as they prosecuted the Second World War.[vii]

Yet simply because certain aspects of a subject are true does not make for a broader “truth.” Heinz Höhne argues the reverse of what some have written in regard to the relationship of the Freikorps and Reichswehr to the Nazis, that in fact the Nazis did not issue from the Freikorps, but rather that many former members of the Freikorps, Imperial Army or the Reichswehr were attracted to the Nazis, particularly to the SS by its “philosophy of “hardness” and its attitude of bellicosity per se, basically unconnected with ideology.”[viii] Others historians state similar views especially those that study the relationship of the Reichswehr leadership to the Freikorps. Thus the thesis of this paper is that the historiography like the period itself is complex; that the composition, leadership and motivations of the Freikorps were not monolithic, nor were they beloved by the Reichswehr, nor were they the “trailblazers” for the Nazi movement. The focus of this article is on the relationship of the Reichswehr and the Freikorps to the Republic to the Kapp Putsch and the dangers of a relationship built on necessity without mutual trust. Such a relationship is dangerous and can lead to unintended consequences. This paper will explore the first years of theWeimarRepublic and specifically look at several key events that were pivotal in the relationship between the Army and Freikorps and the Majority Socialists.

The Leftist “Volksmarine” Division which terrorized Berlin in late 1918 and early 1919

The Leftist “Volksmarine” Division which terrorized Berlin in late 1918 and early 1919

The literature covering this period ranges from well written and researched academic histories and poorly researched and badly done works which attempt to present particular views of the Freikorps which often border on myth. Additionally there are biographical works which shed some light on the subject. The Reichswehr and the German Republic 1919-1926 by Harold Gordon Jr. is perhaps the best study of the Freikorps and their relationship to the state and the army. Gordon’s work is exceptional in documenting the numbers, types, political affiliation, action and ultimate disposition of the Freikorps. Other works which provide exceptional treatment of the relationship between the military and the Republic include The History of the German General Staff by Walter Goerlitz; The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945 by John Wheeler-Bennett, The Reichswehr and Politics 1918-1933 by F.L. Carsten and The Politics of the Prussian Army: 1640-1945 by Gordon A. Craig.

The best of the general histories of the period, which focus on the National Socialist state are The German Dictatorship by Karl Dietrich Bracher, and Richard Evans’ The Coming of the Third Reich. Richard Watt’s The Kings Depart is one of the best for telling the story of the fall of the Empire and the revolution in Germany. Watt’s account is well written and documented work and touches on other factors affecting the new republic including Versailles and Allied political actions. The final chapter of Holger Herwig’s The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918 gives a good account of the Army’s role in the end of the Empire and beginning of the Republic. Andreas Dorpalen’s Hindenburg and the Weimar Republic adds an interesting dimension of Hindenburg’s role in the republic’s formation and negotiations between Groener, Noske and Ebert while Steven Ozments’ history of Germany A Mighty Fortress is superficial in its treatment of the period. Nigel Jones’ Birth of the Nazis: How the Freikorps Blazed a Trail for Hitler is an interesting and somewhat entertaining but poorly documented work. Jones tends to “broad brush” the Freikorps in sometime as “sensationalist” manner. His book has none of the detail or nuance of Gordon, Craig, or Carsten on the Freikorps. Nor does Jones have the depth of Goerlitz or Wheeler-Bennett on the Republic’s relationship with the Army, or the attitude of the Reichswehr leadership to the Freikorps. William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Gerald Reitlinger’s The SS: Alibi of a Nation 1922-1945 and Heinz Höhne’s The Order of the Death’s Head. All of these works add some information which details Nazi involvement in the early part of theWeimarRepublic but are limited in their coverage of the subject.

Of other works, Kenneth Macksey’s Why the Germans Lose at War has an insightful but short chapter dealing with this period and Wolfram Wette’s The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality offers an interesting and at times provocative look at anti-Semitism in the German military in the years following the First World War. Carlos Caballero Jurado’s The German Freikorps 1918-1923 is a short but very detailed study of Freikorps organizations and actions. B.H. Liddell-Hart has a small chapter on General Von Seeckt in The German Generals Talk which hasinteresting commentary on later actions of former Reichswehr officers who served the Nazi state.

Freikorps Von Hulsen being sworn into the Provisional Reichswehr

Freikorps Von Hulsen being sworn into the Provisional Reichswehr

A number of biographies touch on actions of German Officers who played key roles in World War Two.[ix] Most auto-biographies gloss over the Weimar period; however Admiral Reader’s memoir Grand Admiral offers the insight of a naval officer with some direct observation of the revolution and the Kapp Putsch. Guderian in Panzer Leader omits his service in the Baltic “Iron Division.”

The relationship of the Republic to the Army was born in the moment of crisis of the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the armistice discussions with the Allies. Beset by revolts in key naval bases and mutinies aboard ships of the High Seas Fleet and unrelenting Allied pressure on the German armies in the west the situation continued to deteriorate as the “red flag was flying in all the principle cities, soldiers behind the front were electing soldiers councils Russian fashion.”[x] Revolutionary and defeatist propaganda spread by the radical left wing of the Independent Socialists and Spartacus League spread through the country and even affected combat units,[xi] while the “Majority Socialists had found out that the militant factions of the Independents had secretly armed themselves out of funds supplied by the Soviet ambassador and adopted the slogan “all or nothing.””[xii] The situation had deteriorated so badly that Karl Liebknecht, leader of the Spartacus League “was announcing the establishment of a Soviet regime from the steps of the Imperial Palace.”[xiii]

Under these dire conditions, General Wilhelm Groener who had succeeded General Ludendorff as Quartermaster General called an emergency meeting of fifty “of his most senior army commanders.”[xiv] In response to his question of whether the troops would follow the Kaiser and oppose the revolts only one answered in the affirmative, and eight responded that “there was no hope of using regular Army units to quell unrest at home.”[xv] On November 9th Groener went to the Kaiser on behalf of the Supreme Command and in response to a suggestion that the Kaiser lead the Army back and suppress the revolts boldly stated “The Army will march home in peace and under its leaders and commanding generals, but not under the command of Your Majesty, for it stands no longer behind Your Majesty.”[xvi] The Emperor abdicated fleeing to Holland and Friedrich Ebert leader of the Majority Socialists was named Chancellor on November 9th. Upon hearing the news Philipp Scheidemann a leader in the Social Democrats announced that Ebert was Chancellor proclaimed “Long live the great German Republic!”[xvii] It was an ill conceived act as Scheidemann had not consulted Ebert and his act prevented Ebert from working toward an orderly transition of power.

The mobs in the street were not placated by the announcement and the far left organizations aligned with the Independents “had no intention of letting the revolution stop there.”[xviii] In the streets of Berlin soldiers sold their weapons and vehicles officers were attacked by crowds on the streets and whenever “crowds found an Army officer, they tore off his epaulettes and medals.”[xix] Everywhere mutual recrimination was in the air, soldiers “blamed revolutionaries for the betrayal and stab-in-the back while revolutionaries blamed officers for all the costs and losses of the war.”[xx]

Groener called Ebert promising the Army’s support of the new government in return for the government’s assistance to the Army in the maintenance of discipline and supply.[xxi] He also drafted a letter signed by Hindenburg pledging the Army’s loyalty and telling him that “the destiny of the German people is in your hands….”[xxii]One source notes: “Thus, in half a dozen sentences over a telephone line a pact was concluded between a defeated army and a tottering semi-revolutionary regime; a pact destined to save both parties from the extreme elements of revolution but, as a result of which the Weimar Republic was doomed at birth.”[xxiii]

The High Command was able to bring the Army home in good order following the armistice but upon arriving most units “melted away like snow under a summer sun,”[xxiv] those which remained were often shells of their former selves beset by soldier’s councils and leftist revolutionaries. To support the government the High Command issued a directive stating that it “put itself as the disposal of the present government led by Ebert without any reservation.”[xxv]Yet in December delegates of the National Assembly continued to sow resentment in the military by military discipline be placed in the hands of soldiers’ councils, that all badges of rank be removed with all decorations of insignia and honor.[xxvi] Reaction was heated,[xxvii] but despite this Groener, Colonel Walter Reinhardt, the Prussian Minister of War and the Republic’s Defense Minister, Gustav Noske endeavored to find forces to combat the growing revolution and rebellious military units. The choice was not hard, the Army was of no use, so called “democratic forces” were in most cases both unreliable and ineffective, while only the Freikorps “provided suitable material for the immediate creation of an efficient, combat-ready army.”[xxviii] Thus the Freikorps became the instrument of necessity to ensure that the government was not swept away by a Soviet style revolution.

Gustav Noske, of the Majority Socialist party “saw himself as a patriot, a man of action…who had no time for theories…and was one of the few Socialists that the Supreme Command trusted.”[xxix] He had already distinguished himself by helping to bring under control the sailors revolts in Kiel by forming a loyal “Naval Brigade”[xxx] and he “realized that the government must have a dependable military force behind it if it was to survive and rule Germany” and the “old Officer Corps must be the backbone of any such force.”[xxxi] The Army had melted away and units of the workers and soldiers councils were poorly trained, organized and led “”fought against the government as often as for it” and “were of little practical value to either the government or the rebels.”[xxxii] In the chaos of a Spartacus, now called the German Communist Party uprising and vacuum of political leadership of January 1st 1919 agreed to become defense minister stating “Someone must be the bloodhound, I won’t shirk the responsibility!”[xxxiii]

Noske helped by the High Command helped organize volunteer units led by officers and NCOs composed of reliable veterans. Freikorps varied in size from divisions to companies and were led by Generals down to Sergeants and even a Private First Class. Their greatest success was in early 1919 when the Republic was beset by “Red” revolutions in many major cities. Without the use of the Freikorps by the government it is unlikely that the Republic would have survived.[xxxiv] On January 4th Ebert and Noske reviewed the troops of General Maercker’s Freiwillege Landesjaegerkorps and Maercker informed them that every volunteer had pledged loyalty to the government, seeing the discipline and order Noske told Ebert “Don’t worry. Everything is going to turn out all right now.”[xxxv]

On January 5th 1919 the leftist mobs attacked the Chancellery and the officers of the Socialist Vörwarts newspaper. Noske led the Freikorps back into Berlin [xxxvi] to regain control of the city for the government [xxxvii] and crushed the revolt. Among the casualties were Spartacus leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg who were lynched by the officers of the Guards Cavalry Rifle Division.[xxxviii]

In March 1919 after a period of uneasy calm the Freikorps, now reinforced by the 2nd Naval Brigade, or Ehrhardt Brigade[xxxix] were called upon to put down the revolt of the leftist “People’s Naval Division.”[xl] Making liberal use of heavy weapons including tanks the Freikorps inflicted heavy losses on the leftists who lost over 1500 dead and 12,000 wounded in the uprising.[xli] Other revolts were crushed and the Freikorps reached their zenith in Württemberg where Freikorps led by Lieutenant Hahn, a Social Democrat put down leftist revolts[xlii] and in Bavaria where Independents and Communists had taken the city with their “Bavarian Red Army” which numbered nearly 25,000 men[xliii] on April 7th.

After failed attempts by the Socialist led Bavarian government to retake Munich, they asked for Berlin’s help. Violence and massacres of citizens by the various leftist groups inflamed the Freikorps, including the Ehrhardt Brigade and the revolt was crushed by May 2nd.[xliv] Dorpalen called the Freikorps ruthlessness “completely unwarranted in view of the weakness of the opposing forces” and noted though they broke the leftist powers they deepened the nations’ cleavages”[xlv] while Macksey wrote that “where Freikorps’ brutality stained the pages of history there was invariably a forgoing or simultaneous record of excess by their sworn opponents.”[xlvi]

There was a tension between many in the Reichswehr and those on the German left and this came out in many ways as officers were caught in between various political camps while attempting to conduct their duties. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring recounted with great bitterness his experience:

“My cup of bitterness was full when I saw my devoted work rewarded by a warrant for my arrest for an alleged putsch against the socialist-influenced command of my III Bavarian Army Corps. Notwithstanding the degrading episodes during my imprisonment after 1945, I do not hesitate to describe this as the most humiliating moment of my life.”[xlvii]

The end of the Freikorps era began when the Provisional Reichswehr was established on March 6th 1919. The High Command assembled from Freikorps, remaining Army units and Republican defense forces. There was a great distrust between many in the Army, the remaining Freikorps and the Socialists. When the German delegation to Treaty of Versailles signed the treaty under threat of invasion it provoked a crisis. Noske and others threatened resignation over the war guilt clauses, but Groener warned that if the treaty was rejected the Army could not win against the Allies if hostilities were renewed.[xlviii] The treaty imposed harsh limitations on the German Army which many bitterly resented, however, Seeckt, the Chief of Staff of the Army felt that it was “more important to keep the Army in being and preserve the possibility of a military resurrection.”[xlix] Yet by signing the treaty the government lost the support of many officers who looked to General Walther von Lüttwitz, the Reichswehr’s senior commander, and commander of troops in the Berlin area for leadership.[l]

Revolution from the Right: The Kapp Putsch

Revolution from the Right: The Kapp Putsch

Lüttwitz, leaders of certain Freikorps, right-wing groups and individuals made plans to overthrow the government. They favored revolt against the government, but “their political aims were hazy.”[li] Army leadership recognized the threat posed by disaffected Freikorps and their leaders. Seeckt and Reinhardt felt it necessary to demobilize Freikorps who’s ill-discipline and political radicalism was a “danger to the consolidation desired by the army command.”[lii] The plotters sensed a threat to their plans for a putsch and Lüttwitz found a willing co-conspirator in Wolfgang Kapp, a failed politician. Lüttwitz took action when the High Command ordered the 2nd and 3rd Naval Brigades be demobilized in compliance with Versailles treaty limitations and their radical views.[liii] Over the opposition of his chief of staff Von Lüttwitz began planning a coup, in his mind, to save Germany.[liv] The key unit in Lüttwitz plan was the 2nd Naval Brigade Commander by Korvettenkapitän (Lieutenant Commander) Ehrhardt.

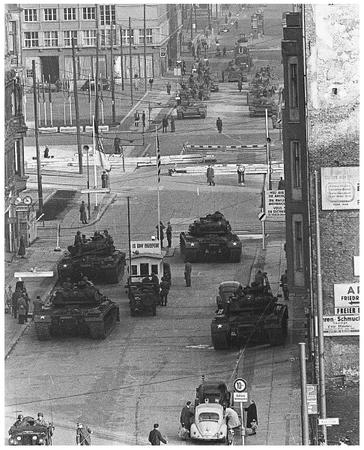

Lüttwitz and his fellow conspirators showed “little regard for coordination of effort” and demonstrated “a quite amazing ability to work at cross purposes.”[lv] On March 12th without consulting Kapp, Lüttwitz and Ehrhardt launched the Putsch and Ehrhardt’s brigade in full battle dress entered Berlin. At this point the Reichswehr command froze; officers refused to condone the putsch but at the same time refused to support Noske and Reinhardt who demanded armed opposition to the coup,[lvi] while most Navy officers openly supported it.[lvii] Seeckt who did not want to see the army set against itself refused to deploy troops to counter Ehrhardt’s men. He declared that “Troops do not fire upon troops!” and “When at occurs, then the true catastrophe, which was avoided with so much difficulty on November 9, 1918 will really occur.”[lviii] Despite the lack of support by the army the coup died amid massive strikes by workers and lack of popular support. However the damage done to the Reichswehr’s relationship to the government, especially the more moderate Majority Socialist was severe.

In the wake of the putsch Noske resigned, many officers in were discredited[lix]and dismissed including Lüttwitz and Admiral Von Trotha, head of the Navy, who openly supported the coup.[lx] Admiral Erich Raeder in his memoirs says that Von Trotha and the Navy staff only” thought of anything of complete loyalty to the government.” [lxi]

However the actions of the Navy leadership showed otherwise. The uncomfortable relationship which had endured the dire days of the Republic was ended. The Reichswehr would emerge a lean and highly trained organization and remain a power broker in the Republic. However the animosity between the Army and the Socialists was now so great that they could not stand together against the Nazis despite their mutual interest in doing so.[lxii]

Conclusion

The period was a critical and complex and should be studied by anyone living in a state with a powerful military tradition and institutions in crisis. Unlike popular notions, the Freikorps were diverse and not the seed-bed of the Nazi movement and though many former members would become Nazis. Several, including Ehrhardt narrowly escaped death at Nazi hands.[lxiii] Freikorps were viewed by Army leadership as an expedient force that could not remain in the service once the Army was functional.

Key lessons include that the military cannot become a “state within a state,” and that both military and civilian leaders must seek to bridge any gulf that separates them in times of crisis. In Weimarboth the military and the Socialists thoroughly distrusted one another with the result that they eventually, despite early success [lxiv] worked against each other in later years. Actions by both Socialists and the military ultimately subverted the Republic and ensured its demise and Seeckt’s policy of separation from politics “tended toward a renunciation of the soldier’s potential restraining influence on adventurous statesmen.”[lxv] Such is the fateful lesson for today for those who suggest a military coup to overturn a government that they oppose in much the same manner as those who supported Lüttwitz, Kapp and Ehrhardt. Such actions only undermine democratic institutions, especially if they are weak and the nation is in crisis. Often such actions bring about regimes far more dangerous than what they seek to overthrow and compromise the integrity of the military.

[i] Jones, Nigel. The Birth of the Nazis: How the Freikorps Blazed a Trail for Hitler. Constable and Robinson Ltd.London,U.K. 1987 and 2004. This is Jones assertion and he attempts to make the tie using careers of some individuals who served both in Freikorps and either in the Nazi Party or Military and attitudes common in many Freikorps with similar attitudes found in the Nazi movement. The 2004 edition of his work includes an introduction by Michael Burleigh echoing his sentiments.

[ii] Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin Group.London,U.K. andNew York,NY. 2003. pp.227-229. Evans discusses the fact that the Nazis did have a number of Freikorps veterans but at no point makes the connection that the Freikorps are a direct ancestor.

[iii] Ozment, Steven. A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People.Harper-Collins Publishers,New York,NY 2004 p.246

[iv] Gordon, Harold J. Jr. The Reichswehr and the German Republic 1919-1926.Princeton University Press,PrincetonNJ 1957. Gordon’s work is perhaps the most detailed study involving the Freikorps and the Reichswehr. He is exceptional in discussing the relationship of both with the various political parties including the Nazis. He refutes this assertion throughout the book.

[v] Bracher, Karl Dietrich. The German Dictatorship. Translated by Jean Steinberg. Praeger Publications, New York, NY 1970. Originally published asDie Deutsche Diktatur: Enstehung, Struktur, Folgen des Nationalsozialismus.Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch,Koln undBerlin. 1969. p.101

[vi] Wheeler-Bennett, John W. The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945. St. Martin’s Press,New York,NY 1954 pp. 91-92

[vii] Shepherd, Ben. War in the Wild East: The German Army and Soviet Partisans.HarvardUniversity Press,Cambridge,MA andLondon,U.K. 2004. p.28

[viii] Höhne, Heinz. The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS. The Penguin Group, London U.K. and New York, NY 1969. Translated by Richard Barry. Originally Published as Der Ordnung unter dem Totenkopf.Verlag der Spiegel,Hamburg, 1966. p.54.

[ix] These include Macksey’s biographies of Kesselring and Guderian , Richard Giziowski’s The Enigma of General Blaskowitz. Peter Padfield’s Dönitz: the Last Führer, David Fraser’s biography of Field Marshal Rommel Knight’s Cross, Messenger’s work on Von Rundsedt, The Last Prussian, and Höhne’s Canaris: Hitler’s Master Spy all provide brief but interesting views of the actions and attitudes of these officers during the revolution and during the Weimar period.

[x] Goerlitz, Walter. History of the German General Staff 1657-1945.Translated by Brian Battershaw. Westview Press. Boulder CO and London. 1985 Originally published as Der Deutsche Generalstab, Verlag der Fankfurter Hefte, Frankfurt am Main. FirstU.S. publication in 1953 by Preager Publishers. p.200

[xi] Gordon, Harold Jr. The Reichswehr and the German Republic 1919-1926.Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1957 pp.4-5 Gordon recounts the story of an entire replacement train revolting when it reached the front which had to be disarmed by a shock battalion.

[xii] Watt, Richard M. The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany: Versailles and the German Revolution. Simon andSchuster,New York, NY 1968. p.186

[xiii] Wheeler-Bennett, John W. The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945. St. Martin’s Press,New York,NY 1954. p.18

[xiv] Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria Hungary 1914-1918. Arnold Press a member of the Hodder-Headline Group,London,UK andNew YorkNY 1997 p.445

[xv] Ibid. Herwig. p.445

[xvi] Carsten, F.L. The Reichswehr and Politics 1918-1933. Oxford University Press,Oxford,UK 1966 p.6. It is noted by a number of author’s that Groener did this, to maintain the unity ofGermany and prevent its division.

[xvii] Ibid. Watt. p.196 Watt notes Ebert’s reaction as being enraged as the proclamation of the Republic technically “invalidated the existing constitution;Germany was now technically without a government.” (p.197)

[xviii] Ibid. Watt. p.197

[xix] Ibid. Watt. p.197

[xx]Giziowski, Richard. The Enigma of General Blaskowitz Hippocrene Books Inc.New YorkNY, 1997. p.65

[xxi] Craig, Gordon A. The Politics of the Prussian Army 1640-1945. Oxford University Press,Oxford,UK 1955 pp.347-348. Craig gives an interesting account noting the Groener’s call to Ebert shows recognition of the legitimacy of the new government and notes that the offer was somewhat conditional.

[xxii] Dorpalen, Andreas. Hindenburg and the Weimar Republic. PrincetonUniversity Press,Princeton,NJ. 1964 p.26

[xxiii] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett. p.21

[xxiv] Ibid. Gordon. p.15

[xxv] Ibid. Carsten. p.11. This was of critical importance as Carsten later notes that the Army realized that the government could not survive without its support. Groener was perhaps the officer who most recognized the situation and endeavored to ensure that “the best and the strongest element of the oldPrussia, was saved for the newGermany, in spite of the revolution.” (p.12)

[xxvi] Ibid. Carsten. p.18 Carsten produces the bulk of the English translation of these points and notes that the anti-military feeling had become widespread.

[xxvii] Ibid. Giziowski. p.66 Giziowski recounts the speech of Hermann Goering in response to the announcement. This shows how such treatment can breed anger and resentment in a military that feels it has been betrayed after serving its country in a long and difficult war: For four long years we officers did our duty and risked all for the Fatherland. Now we have come home, and how do they treat us? The spit on us and deprive us of what we gloried in wearing. I will tell you that the people are not to blame for such conduct. The people were are comrades…for four long years. No, the ones who have stirred up the people, who have stabbed this glorious army in the back…. I ask everyone here tonight to cherish a hatred, a deep and abiding hatred, for these swine who have outraged the German people and our traditions. The day is coming when we will drive them out of ourGermany.”

[xxviii] Ibid. Gordon. p.15

[xxix] Ibid. Watt. p.168

[xxx] Ibid. Gordon. pp. 19 and 24. This was the 1st Marine Brigade, or Brigade Von Roden of which elements would later serve in under the command of other Freikorps such as the Guards Calvary Rifle Division.

[xxxi] Ibid. Gordon. p.14

[xxxii] Ibid. Gordon. p.18

[xxxiii] Ibid. Watt. p.239

[xxxiv] Ibid. Gordon. p.426

[xxxv] Ibid. Watt. p.247

[xxxvi] Thee forces included the Landesjaegerkorps and Guards Cavalry Rifle division.

[xxxvii] Ibid. Gordon. p.30

[xxxviii] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett. p.36

[xxxix] This was one of two additional Naval Brigades formed by Noske after the success of Naval Brigade Von Roden. It was one of the most combat effective but unfortunately violent and radical of the Freikorps, it would as we will see be a key unit in the Kapp Putsch but would not be absorbed into the Reichswehr.

[xl] This unit was not a Navy unit at all but was composed of many who were criminals and other rabble. See Gordon, Carsten and Watt.

[xli] Jurado, Carlos Caballero. The German Freikorps 1918-23. Illustrated by Ramiro Bujeiro. Osprey Publishing,Oxford,UK 2001 p.12

[xlii] Ibid. Gordon. p.42 His units were known as Security Companies.

[xliii] Ibid. Jurado. p.13

[xliv] Ibid. Gordon. pp.47-49. An estimated 550 people including 200 innocent bystanders were killed in the fighting.

[xlv] Ibid. Dorpalen. p.29

[xlvi] Macksey, Kenneth. Guderian: Creator of the Blitzkrieg. Stein and Day Publishing,New York,NY 1975 p.45

[xlvii] Kesselring, Albrecht. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Kesselring with a new introduction by Kenneth Macksey. Greenhill Books, London UK. 1997. Translated from the German by William Kimber Ltd. Originally published as Soldat bis zum letzen Tag. Athenaum,Bonn,Germany 1953 pp.18-19

[xlviii] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett. pp.57-59

[xlix] Ibid. Goerlitz. p.216

[l] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett. p.61

[li] Ibid. Carsten. p.74

[lii] Ibid. Carsten. pp.74-75

[liii] Ibid. Carsten. p.76 Another consideration is that Noske, Reinhardt and Seeckt all were seeking to retire Lüttwitz.

[liv] Ibid. Gordon. p.97

[lv] Ibid. Craig. p.376

[lvi] Ibid. Carsten. pp.78-79

[lvii] Höhne, Heinz. Canaris: Hitler’s Master Spy. Cooper SquarePress,New York,NY 1979 and 1999. Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn, Originally published inGermany by C. Bertelsmann Verlag Gmbh, München. 1976. p. 78. Canaris also had been suspected of complicity in the murders of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht but was acquitted. (pp.56-71)

[lviii] Ibid. Gordon. pp.114-115

[lix] Among them Maercker who had been such a strong supporter of the Republic in the early days.

[lx] Ibid. Carsten. p.98

[lxi] Raeder, Erich. Grand Admiral. Translated from the German by Henry W. Drexell.United States Naval Institute,AnnapolisMD, 1960. Da Capo Press edition published 2001. p.111. This is interesting as almost all histories implicate the Navy High Command of either some complicity or at least agreement with the Putsch participants.

[lxii] The final part in the drama would come when General Kurt Von Schleicher became the last Chancellor before Hitler. Schleicher had assisted Groener and Noske in the early days of the Republic and often attempted to use the Army’s influence in politics. He was fatally short sighted and was a victim of the SS “night of Long Knives” which was directed against the SA.

[lxiii] Ibid. Jones. p.266 Others such as Gerhard Rossbach had similar experiences. Korvettenkapitän Löwenfeld of the 3rd Naval Brigade became an Admiral, Wilhelm Canaris , who was implicated in the Kapp Putsch but kept his career would later head the Abwehr and die in a concentration camp.

[lxiv] Ibid. Gordon. p.426 Gordon has a good discussion of this topic in his conclusion.

65 Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Published 1948 B.H. Liddell-Hart, Quill Publications,New York,NY. 1979. p.18 Liddell-Hart’s analysis of the results of the Reichswehr’s disconnection from the larger society and political process is remarkable due to current trends in the American military which like the Reichswehr has become somewhat more conservative and disconnected from society, exceptionally technically proficient but not adept in politics or grand-strategy.

Works Cited

Bracher, Karl Dietrich. The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure and Effects of National Socialism. Translated from the German by Jean Steinberg with an introduction by Peter Gay. Praeger Publishers, New York, NY. 1970 Originally published in Germany as Die deutsche Diktator: Entstehung, Struktur, Folgen den Nationalsozialismus by Verlag Kiepenheuer und Witsch.Koln undBerlin.

Carsten, F.L. The Reichswehr and Politics 1918-1933. OxfordUniversity Press,Oxford,UK 1966

Craig, Gordon A. The Politics of the Prussian Army 1640-1945. OxfordUniversity Press,Oxford,UK 1955

Dorpalen, Andreas. Hindenburg and the Weimar Republic. PrincetonUniversity Press,Princeton,NJ. 1964

Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin Books,New York,NY andLondon,UK. 2003

Giziowski, Richard. The Enigma of General Blaskowitz. Hippocrene Books Inc.New YorkNY, 1997

Goerlitz, Walter. History of the German General Staff 1657-1945. Translated by Brian Battershaw. Westview Press. Boulder CO and London. 1985 Originally published as Der Deutsche Generalstab, Verlag der Fankfurter Hefte, Frankfurt am Main. FirstU.S. publication in 1953 by Preager Publishers

Gordon, Harold Jr. The Reichswehr and the German Republic 1919-1926. PrincetonUniversity Press,Princeton,NJ 1957

Guderian, Heinz. Panzer Leader. (abridged) Translated from the German by Constantine Fitzgibbon, Ballantine Books,New York 1957

Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria Hungary 1914-1918. Arnold Press a member of the Hodder-Headline Group,London,UK andNew YorkNY 1997

Höhne, Heinz. Canaris: Hitler’s Master Spy. Cooper SquarePress,New York,NY 1979 and 1999. Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn, Originally published inGermany by C. Bertelsmann Verlag Gmbh, München. 1976.

Höhne, Heinz. The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS. The Penguin Group, London U.K. and New York, NY 1969. Translated by Richard Barry. Originally Published as Der Ordnung unter dem Totenkopf. Verlagder Spiegel,Hamburg, 1966.

Jones, Nigel. The Birth of the Nazis: How the Freikorps Blazed the Way for Hitler. Constable and Robinson Ltd.London,UK 1987

Jurado, Carlos Caballero. The German Freikorps 1918-23. Illustrated by Ramiro Bujeiro. Osprey Publishing,Oxford,UK 2001

Kesselring, Albrecht. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Kesselring with a new introduction by Kenneth Macksey. Greenhill Books, London UK. 1997. Translated from the German by William Kimber Ltd. Originally published asSoldat bis zum letzen Tag. Athenaum,Bonn,Germany 1953.

Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Published 1948 B.H. Liddell-Hart, Quill Publications,New York,NY. 1979

Macksey, Kenneth. Guderian: Creator of the Blitzkrieg. Stein and Day Publishing,New York,NY 1975

Macksey, Kenneth. Kesselring: The German Master Strategist of the Second World War. Greenhill Books,London,UK 2000.

Ozment, Steven. A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People.Harper-Collins Publishers,New York,NY 2004

Shepherd, Ben. War in the Wild East: The German Army and Soviet Partisans.HarvardUniversity Press,Cambridge,MA andLondon,U.K. 2004

Wheeler-Bennett, John W. The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945. St. Martin’s Press,New York,NY 1954

Watt, Richard M. The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany: Versailles and the German Revolution. Simon andSchuster,New York, NY 1968

Wette, Wolfram. The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA and London, UK 2006. Translated from the German by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Originally published as Die Wehrmacht: Feindbilder, Vernichtungskrieg, Legenden. S. Fischer Verlag Gmbh,Frankfurt am Main,Germany 2002

The Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch Spartacists Attempt to Overthrow the Republic

Spartacists Attempt to Overthrow the Republic Threats to the Republic: The People’s Naval Division Terrorized Berlin

Threats to the Republic: The People’s Naval Division Terrorized Berlin General Wilhelm Groener Who Worked with Socialist Leaders Friedrich Ebert and Gustav Noske to Save the Republic against a Soviet Style Revolution

General Wilhelm Groener Who Worked with Socialist Leaders Friedrich Ebert and Gustav Noske to Save the Republic against a Soviet Style Revolution General Hans Von Seeckt Creator of the Reichswehr Believer that it Needed to be Apolitical

General Hans Von Seeckt Creator of the Reichswehr Believer that it Needed to be Apolitical  Gustav Noske Reviewing Freikorps Hulsen Which was Formed out of Existing Army Units by General von Hulsen

Gustav Noske Reviewing Freikorps Hulsen Which was Formed out of Existing Army Units by General von Hulsen Noske with General Von Luttwitz

Noske with General Von Luttwitz Lieutenant Commander Ehrhardt Commander of the 2nd Naval Brigade during the Kapp Putsch, although a Hard Line Conservative Ehrhardt would Suffer under the Nazis

Lieutenant Commander Ehrhardt Commander of the 2nd Naval Brigade during the Kapp Putsch, although a Hard Line Conservative Ehrhardt would Suffer under the Nazis President Friedrich Ebert with Von Seeckt and other Military Leaders

President Friedrich Ebert with Von Seeckt and other Military Leaders Freikorps Rossbach During the Kapp Putsch. One of the Most Extreme Freikorps it was Demobilized and Broken up a number of its Leaders including Rossbach Found Their Way to the Nazis

Freikorps Rossbach During the Kapp Putsch. One of the Most Extreme Freikorps it was Demobilized and Broken up a number of its Leaders including Rossbach Found Their Way to the Nazis The Ehrhardt Brigade During the Kapp Putsch

The Ehrhardt Brigade During the Kapp Putsch Admiral Von Trotha head of the Navy was Sacked for Supporting the Putsch

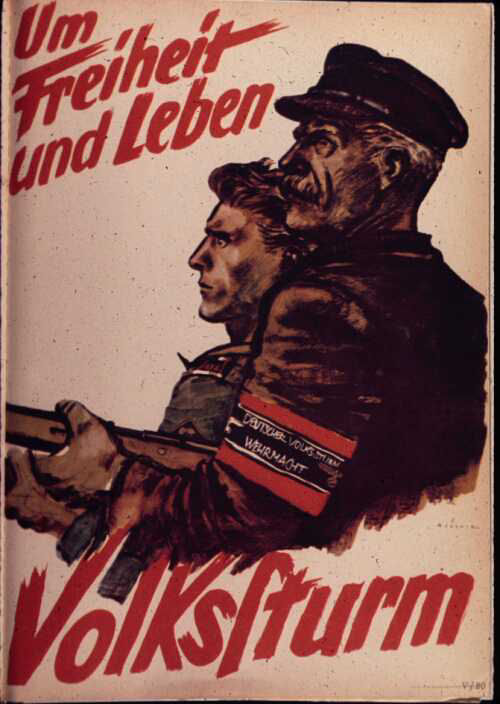

Admiral Von Trotha head of the Navy was Sacked for Supporting the Putsch Volksturm Members

Volksturm Members Volksturm receiving training on Panzerfaust Anti-Tank Rocket

Volksturm receiving training on Panzerfaust Anti-Tank Rocket Volksturm Propaganda Poster

Volksturm Propaganda Poster Ludwig Beck Bundesarchiv Foto

Ludwig Beck Bundesarchiv Foto Ludwig Beck Kasserne Sonthofen

Ludwig Beck Kasserne Sonthofen