The following is an article that I first published on this site in 2009 “The Ideological War: How Hitler’s Racial Theories Influenced German Operations in Poland and Russia.” Since I am getting ready to write a number of articles on the subject of politicized military and police forces, the Concentration Camps and the Einsatzgrüppen I wanted to give my readers an overview of the subject. The focus is the ideology that framed and justified to the perpetrators the mass murders of Jews, Poles, Russians and others during the German invasions of Poland and the Soviet Union. I will be writing about policy as well as key personalities involved in the planning and execution of these crimes over the coming months since I have renewed my studies of the crimes and their prosecution at Nuremberg over the past year. In a sense this article is simply an introduction to more specific articles that I will write.

Peace, Padre Steve+

Introduction: Ideology and Genocide

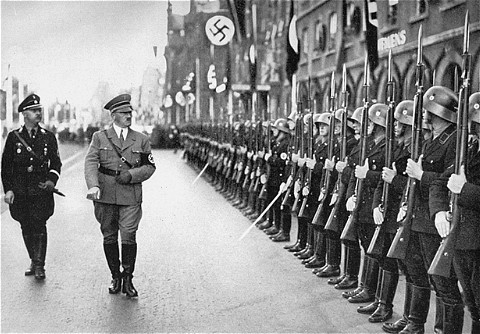

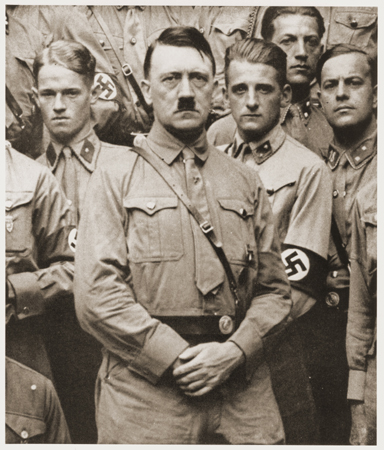

Architects of Annihilation: Heinrich Himmler with Adolf Hitler

The German war against the Soviet Union was the first truly race-based ideological war in history with the campaign against Poland its precursor. Adolf Hitler’s racial theories and beliefs played a dominant role in Germany’s conduct of the war in the East in both the military campaign and occupation. This has become clearer in recent years as historians have had the opportunity to examine Hitler’s writings, those of senior Nazi officials and military officers and documents which had been unavailable until the end of the Cold War. Understanding the Nazi ideological basis and the underlying cultural prejudice against the Jews and eastern Europeans in general is foundational to understanding Hitler’s conduct of the war and why the destruction of the Jews figured so highly in his calculations. One must also understand the military and police cultures and doctrines that enabled them to cooperate so closely in the conduct of the war.

The German war in the east would differ from any previous war. Its underlying basis was ideological. Economic and geopolitical considerations were given importance in relationship to the understanding of the German “Master Race.” Race and Lebensraum was the goal of the State that “concentrates all of its strength on marking out a way of life for our people through the allocation of Lebensraum for the next one hundred years…the goal corresponds equally to the highest national and ethnic requirements.[1] Hitler believed that Germany was “entitled to more land…because it was the “mother of life” not just some “little nigger nation or another.”” [2] The Germans planned to “clear” the vast majority of the Slavic population and the “settlement of millions of hectares of eastern Lebensraum with German colonists” complimented by a short term exploitation of the land to “secure the food balance of the German Grossraum.”[3] Joachim Fest notes that Hitler called it a “crime” to wage war only for the acquisition of raw materials. Only the issue of living space permitted resort to arms.”[4]

Previous wars emphasized conquest of territory and natural resources be they for empire or self sufficiency. The Thirty Years War had a heavy religious component but was more about increasing the power of emerging nation states led by men not necessarily loyal to their religious brethren.[5] The American and Russian Civil wars had some ideological basis and helped usher in the brutality of total war. Both had major effect in these nations’ development and both were bitterly contested with the winners imposing to various degrees political changes on their vanquished brothers they were civil wars.[6] While Adam Tooze sees the Holocaust as the first step of the “last great land grab in the long and bloody history of European colonialism…”[7] this argument does not take away from the basic premise that the war was at its heart ideological.

The root of this war was in the mind of Adolf Hitler himself. His years in Vienna were foundational as he absorbed the ideas of Pan-German, anti-Semitic groups and newspapers like the Deutsches Volksblatt. [8] In Vienna he made the connection between the Jews and Marxism.[9] Joachim Fest notes that in Vienna Hitler became obsessed by the fear of the Slavs and Jews, hated the House of Hapsburg, the Social Democratic Party, and “envisioned the end of Germanism.”[10] His racial views were amplified after the war in turbulent Weimar Germany where he became a member of the NDSAP, rising rapidly within it, eventually taking over party leadership, reorganizing it so that it “became the instrument of Hitler’s policies.”[11] Following the unsuccessful Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 Hitler wrote Mein Kampf while imprisoned in the Landsberg prison in which he enunciated his views about the Jews, Slavs and Lebensraum. Hitler believed that Imperial Germany had been “hopelessly negligent” in regard to the Jews[12] and that the Jews in conjunction with the Catholic Center Party and Socialists worked together for “maximum damage to Germany.”[13] Likewise he saw the Jews as heading the “main ideological scourges of the nineteenth and twentieth century’s.”[14] It was the ideology of Hitler’s “obsessive anti-Semitism”[15] that drove Nazi Germany’s policy in regard to the Jews and against Jewish-Bolshevism.

By the 1920s Hitler had “combined his hatred of the Jews and of the supposedly Jewish dominated Soviet state with existing calls to conquer additional Lebensraum, or living space, in the east.”[16] Hitler wrote: “The fight against Jewish world Bolshevism requires a clear attitude toward Soviet Russia. You cannot drive out the Devil with Beelzebub.”[17] Richard Evans notes that Mein Kampf clearly enunciated that “Hitler considered racial conflict…the essence of history, and the Jews to be the sworn enemy of the German race ….” And that the “Jews were now linked indissolubly in Hitler’s mind with “Bolshevism” and “Marxism.” [18] When Hitler became the dictator of Germany “his ideology and strategy became the ends and means of German foreign policy.”[19] His aims were clear, Hitler remarked to Czech Foreign Minister Chvalkovsky on 21 January 1939: “We are going to destroy the Jews.”[20] It was clear that Hitler understood his own role in this effort noting to General Heinrici that “he was the first man since Charlemagne to hold unlimited power in his own hand. He did not hold this power in vain, he said, but would know how to use it in the struggle for Germany…”[21]

This study will focus on the German policy of ideological-racial war in Poland and Russia. The German war against the Soviet Union and to a certain extent Poland was waged with an unforgiving ferocity against Hitler’s enemy, the Jewish-Bolshevik state and the Slavic Untermenschen. It was characterized by the rise of “political-ideological strategy”[22] in which “Barbarossa showed the fusion of technocracy and ideology in the context of competitive military planning.”[23]

Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel “war was a fight for survival….dispense with outdated and traditional ideas about chivalry and the generally accepted rules of warfare…” Bundesarchiv Bild

Hitler’s “ideological and grandiose objectives, expressed in racial and semi-mystical terms, made the war absolute.”[24] Field Marshal Keitel noted a speech in March 1941 where Hitler talked about the inevitability of conflict between “diametrically opposed ideologies” and that the “war was a fight for survival and that they dispense with their outdated and traditional ideas about chivalry and the generally accepted rules of warfare.”[25] General Halder, Chief of the OKH in his War Dairy for that meeting noted “Annihilating verdict on Bolshevism…the leaders must demand of themselves the sacrifice of understanding their scruples.”[26] Based on Lebensraum and race, the German approach to war would combine “racism and political ideology” for the purpose of the “conquest of new living space in the east and its ruthless Germanization.”[27] Hitler explained that the “struggle for the hegemony of the world will be decided in favor of Europe by the possession of the Russian space.”[28] Conquered territories would be “Reich protectorates…and that these areas were to be deprived of anything in the nature of a Slav intelligentsia.”[29] This goal was manifest in the “Criminal Order” issued by OKW which stated that the war was “more than mere armed conflict; it is a collision between two different ideologies…The Bolshevist-Jewish intelligentsia must be eliminated….”[30] Other displaced inhabitants of the conquered eastern lands would be killed or allowed to starve.[31] Part of this was due to economic considerations in the Reich, which gave Germans priority in distribution of food, even that from the conquered lands. Starvation was a population control measure that supplemented other forms of annihilation.[32] As Fest notes in Russia Hitler was “seeking nothing but “final solutions.””[33] Despite numerous post-war justifications by various Wehrmacht generals, the “Wehrmacht and army fell into line with Hitler because there was “a substantial measure of agreement of “ideological questions.””[34]

Ideology was key to Hitler’s worldview and fundamental to understanding his actions in the war.[35] However twisted Hitler’s ideological formulations were his ideas found acceptance beyond the Nazi faithful to the Army and Police, who would execute the campaigns in Poland and Russia in conjunction with the Einsatzgrüppen and Nazi party organizations. In these organizations he found allies with pre-existing cultural, political and doctrinal understandings which allowed them to be willing participants in Hitler’s grand scheme of eastern conquest.

Doctrinal and Ideological Foundations

While Hitler’s racial ideology was more extreme than many in the German military and police, these organizations had cultural beliefs and prejudices as well as doctrinal and ideological foundations which helped them become willing accomplices to Hitler. These factors were often, consciously or unconsciously, excluded from early histories of World War II. The Allies relied on German officers to write these histories at the beginning of the Cold War, developing the “dual myth of German military brilliance and moral correctness.”[36] B.H. Liddell-Hart makes the astounding statement that “one of the surprising features of the Second World War was that German Army in the field on the whole observed the rules of war than it did in 1914-1918-at any rate in fighting its western opponents….”[37] While he might be excused by lack of knowledge of German army atrocities, not just the SS who he blamed the atrocities, it helps present a myth as truth.[38] The myths were helped by the trials of Manstein and Kesselring where “historical truth had to be sacrificed…to the demands of the Cold War.”[39] Kenneth Macksey confronts the myth that only the “Waffen SS committed barbaric and criminal acts” noting: “Not even the Knights of the Teutonic Order and their followers in the Middle Ages sank to the depths of the anti-Bolshevik Wehrmacht of 1941.”[40]

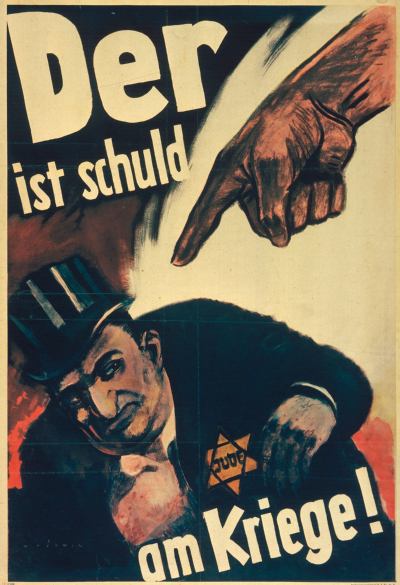

Pre-Nazi Exterminator: General Lothar Von Trotha led the Genocide against the Herero in Namibia

Germany had a long running history of anti-Semitism before Hitler. German anti-Semitism often exhibited a “paranoid fear of the power of the Jews,”[41] and included a “fashionable or acceptable anti-Semitism”[42] which became more pronounced as the conditions of the Jews became better and Jews who had fled to Eastern Europe returned to Germany.[43] Sometimes this was tied to religious attitudes, but more often focused on the belief that the Jews “controlled certain aspects of life” and presented in “pseudo-scientific garb” along with the “myth of a secret Jewish plot for world domination which was simultaneously part of the internationalism of Freemasonry.”[44] Admiral Wilhelm Canaris provides an example as he “had grown up in the atmosphere of “moderate” anti-Semitism prevailing in the Ruhr middle class and in the Navy believed in the existence of a “Jewish problem”” and would “suggest during 1935-1936 that German Jews should be identified by a Star of David as special category citizens….”[45] Wehrmacht soldiers were “subject to daily doses of propaganda since the 1930s” and that with the “start of the Russian campaign propaganda concerning Jews became more and more aggressive.”[46] Some objected to Nazi actions against Jews. Von Manstein protested the “Aryan paragraph” in the Reichswehr on general principal.”[47] Yet some who planned and executed the most heinous crimes like Adolf Eichmann had “no fanatical anti-Semitism or indoctrination of any kind.”[48]

The military “looked to the regime to reshape society in every respect: political, ideological, economic and military…Propaganda would hammer home absolute nature of the struggle…”[49] Ideological training began in the Hitler Youth and Reichsarbeitsdienst and produced a soldier in which “Anti-Semitism, anti-communism, Lebensraum – these central tenants of Nazism were all inextricably linked with the Landser’s conception of duty, with his place and role in the vast machinery of war.”[50] Following the dismissal of General Fritsch in 1938, General Brauchitsch promised that “he would make every effort to bring the Army closer to the State and the State’s ideology.”[51] Alfred Novotny, a Austrian soldier in the Gross Deutschland division noted how training depicted the Russians as Untermenschen and how they were “subjected to official rantings about how the supposedly insidious, endless influence of the Jews in practically every aspect of the enemy’s endeavors…Jews were portrayed as rats, which were overrunning the world….”[52] This added to the already “harsh military discipline” which had a long tradition in Germany conditioning soldiers to violence and brutalization of their enemy. Similar programs existed in the Order Police which would play a large part in the eastern campaign, the “image of “treasonous” leftists and Jews helped shape the personal and political beliefs of many policemen throughout the interwar period.”[53] Even ordinary police training before the war in German speaking Europe was brutalizing.”[54] These troops were recipients of an ideological formation which “aimed at shaping the worldview of the police leading to the internalization of belief along National Socialist lines.”[55] Waffen SS soldiers, especially those of the Totenkopf division were subjected to even more systematic political indoctrination on the enemies of National Socialism, the Jews, freemasonry, Bolshevism and the churches.[56]

Along with cultural anti-Semitism and the Nazification of German thought in the 1930s, there were aspects of military doctrine which helped prepare the way for the eastern campaign. The most important were the Army’s anti-partisan and rear area security doctrine. The history of security anti-partisan operations dated back to the Prussian Army’s Ettapen, which began in 1813 with the Landwehr’s role in security against looters and others.[57] These units supported and supplied offensive operations from the rear to the combat zone with a secondary mission of countering partisans and preventing disruptions in the rear area. The Ettapen would be reformed and regulated in 1872 following the Franco-Prussian War.[58] The German experience fighting guerrillas and partisans, the francs-tireurs in the Franco-Prussian War, “scarred the Army’s institutional mentality.”[59] Von Moltke was “shattered,” writing his brother that “war was now taking on an ever more hate-inspired character.”[60] He was “appalled by improvised armies, irregular elements, and appeals to popular passion, which he described as a “return to barbarism.”[61] He wrote: “Their gruesome work had to be answered by bloody coercion. Because of this our conduct of the war finally achieved a harshness that we deplored, but which we could not avoid.”[62] The brutal German response to the franc-tireurs found legal justification in Franz Lieber’s principles for classification of belligerents and non-belligerents, which determined that guerrillas were outlaws or bandits.[63] In response, the Germans systematically reorganized the Ettapen to include railroad and security troops, special military courts, military police, intelligence and non-military police, including the Landespolizei and the Grenzschutzpolizei.[64]

The doctrinal response to partisans, or as they would become known in German writings as “bandits,” was that bandits should be encircled and destroyed. This was employed in the Southwest Africa German colonies. The Germans, influenced by the experience in France, “displayed a ferocity surpassing even that of the racially brutalized campaigns of its imperialist peers.”[65] The campaign against the Herero tribes which resisted the occupation of Namibia from 1904-1912 utilized encirclement operations, racial cleansing and what would become known as Bandenkämpfung operations.[66] This was further developed in the First World War, especially in the east where General Fritz Gempp described the security problem as a “ruthless struggle” in which German pacification policy “was in reality the application of terror to galvanize the population into accepting German rule.”[67] Anti-partisan doctrine was codified in the Truppenführung of 1933 which stated that “area defense against partisan warfare is the mission of all units” and that the preferred method of combating partisan bands was that they be surrounded and destroyed.[68] General Erhard Rauss later described active and passive measures used to deal with partisans, focusing on the tactic of encirclement to destroy the enemy.[69]

Anti-partisan doctrine focused on the destruction of the partisans, was coupled a total war philosophy and provided fit well with Hitler’s radical ideology. The “propensity for brutality in anti-guerrilla warfare was complimented by officers’ growing preoccupation, both during and after World War I, with the mastery and application of violence.”[70] Michael Geyer notes: “ideological mobilization for the creation of a new national and international order increasingly defined the parameters of technocratic planning.”[71] The acceptance of long used brutal tactics to destroy the enemy combined with Hitler’s radical racial animus against the Jews could only be expected to create a maelstrom in which all international legal and moral standards would be breached.

Beginnings in Poland

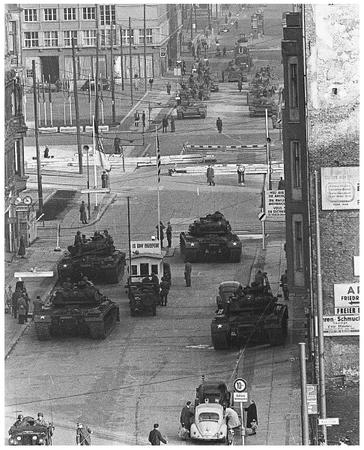

Einsatzgrüppen in Poland

The Polish campaign was a precursor to the Russian campaign and was not totally race driven. It contained elements of Germany’s perception of the injustice of Versailles which gave Poland the Danzig corridor and Germany’s desire to reconnect East Prussia to the Reich, as well as the perceived necessity to remove a potential enemy from its rear as it faced France, yet it was a campaign steeped in Nazi racial ideology. Poland resisted German efforts to ally itself with Germany in 1939, thus Hitler determined it “would be crushed first.”[72] Meeting with military leaders on 23 May 1939 Hitler “made it plain that the real issue was not Danzig, but securing of Germany’s Lebensraum….”[73] On 22 August he enjoined the generals to “Close your hearts to pity! Act brutally! Eighty million people must obtain what is their right.”[74]

General Johannes Blaskowitz

Even so, most military leaders failed to appreciate what Hitler was calling on them to do; Manstein would note that “what Hitler had to say about an eventual war with Poland, could not, in my opinion, be interpreted as a policy of annihilation.”[75] Others such as Canaris was “utterly horrified” as he read his notes to his closest colleagues “His voice trembled as he read, Canaris was acutely aware that he had witnessed something monstrous.”[76] General Johannes Blaskowitz, commander of 8th Army who would be the military commander in Poland did not leave any notes about the meeting, but his biographer notes that he “may have naively attached a military meaning to these terms since he was busy with military matters and soon to begin operations.”[77] This was the interpretation of Manstein as well.[78] Keitel noted that the speech was “delivered in the finest sense of psychological timing and application,” molding “his words and phrases to suit his audience.”[79] In light of the mixed interpretations by military leaders, it is possible that many misinterpreted Hitler’s intent and did not fully appreciated his ideology as they went into Poland, carefully secluding themselves in the narrow confines of their military world. While such an explanation is plausible for some, it is also true that many others in light of subsequent actions were in full agreement with Hitler. One author notes that “no man who participated in the Führer Conferences….and there were present the highest ranking officers of the three services, could thereafter plead ignorance of the fact that Hitler had laid bare his every depth of infamy before them, and they had raised no voice in protest either then or later.”[80] In July, General Wagner, the Quartermaster General issued orders that “authorized German soldiers to take and execute hostages in the event of attacks by snipers or irregulars.”[81]

Regardless of the meaning ascribed to Hitler’s speech, Hitler had already laid plans to destroy the Jews in Poland and decimate the Polish intelligentsia and leadership. Hitler gave Himmler the task of forming “Einsatzgrüppen to follow the German troops as they advanced into Poland and liquidate Poland’s upper class wherever it was to be found.”[82] While senior party leaders remained at Hitler’s side following the conference, Himmler worked to coordinate his troops, including the reinforced Totenkopf battalions and Einsatzgrüppen with the Army.[83]

SS Obergruppenfuhrer Reinhard Heydrich: Hitler’s Hangman

Himmler began planning in early May and the Army decided to “use SS and police units to augment their own forces for security tasks.”[84] Himmler established “five Einsatzgrüppen to accompany each of the numbered German armies at the start of the campaign.”[85] Placed under the aegis of Reinhard Heydrich the groups were broken down into smaller units of 100-150 men and allotted to army corps. All senior posts were occupied by officers of the SS Intelligence Service the SD or Sicherhietsdienst.[86] Two additional groups were formed shortly after the invasion.[87] Additionally 3 regiments of the SS Totenkopfverbande, under the direction of SS General Theodore Eicke were deployed in the rear areas of the advancing armies.[88] The purpose of these units was shielded from the Army in the planning stages,[89] although Heydrich worked with the Army to develop lists of up to 30,000 people to be arrested.[90] To eliminate the Polish elites without disturbing the Army, Himmler and Heydrich gave the Army “only the bare minimum of information.”[91] The deception was initially successful. Blaskowitz’s 8th Army defined the mission of the Einsatzgrüppen in a traditional manner, noting their mission as “the suppression of all anti-Reich and anti-German elements in the rear of the “fighting troops, in particular, counter espionage arrests of politically unreliable persons, confiscation of weapons, safeguarding of important counter-espionage materials etc…”[92] General Wagner issued orders in July 1939 that “authorized German soldiers to take and execute hostages in the event of attacks by snipers or irregulars.” Despite the deception, there was no way to disguise the murder of Polish intelligentsia and Jews, and had the Army had the political acumen it could have considerably restricted the terror campaign.[93] .

The campaign demonstrated Hitler’s intent. Heydrich talked about the “murdering the Polish ruling class” of the aristocracy, Catholic clergy, communists and Jews on 7 September.[94] The Army moved east with the Einsatzgruppen and Totenkopf Verbande, conducting arrests and executions in its wake. The Army worried about Polish soldiers left behind in rear areas, and a paranoia developed as some generals believed that a “brutal guerilla campaign has broken out everywhere and we are ruthlessly stamping it out.”[95] Yet some actions against the Polish elites and the Jews drew Army reactions. The unit commanded by SS General Woyrsch “behaved with such unparalleled bestiality that it was throw out of the operational area” by General List of 14th Army.[96] Totenkopfverbande Brandenburg came to Army attention when its commander remarked that the “SSVT would not obey Army orders,” and the conclusion of the Army General was that “the SSVT commander was following orders from some non-military authority to terrorize the local Jews.”[97]

These atrocities as well as those of other Waffen-SS units were hard to hide and brought reactions out of army commanders who sought to punish the offenders. Blaskowitz and others attempted to put a halt to SS actions against Poles and Jews,[98] but most officers turned a blind eye to the atrocities or outright condoned them. It is believed that General Walter Model and others “not only knew what was occurring in Poland but actually took part in what Halder himself described in October as “this devilish plan.””[99] It appears that many who objected were not motivated so much by humanitarian, moral or legal considerations, but rather by the effect on good order and discipline.[100] Likewise it is clear that many officers, even if they did not participate in the actions probably approved of them. Many biographies and histories of this period written by authors influenced by surviving German officers make no or little mention of the Army’s part in these actions.

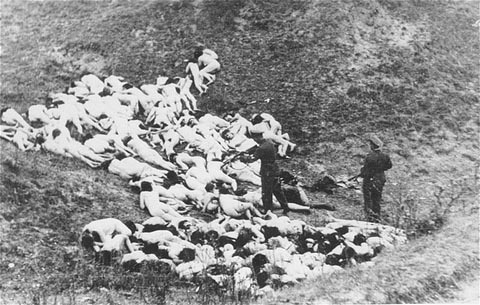

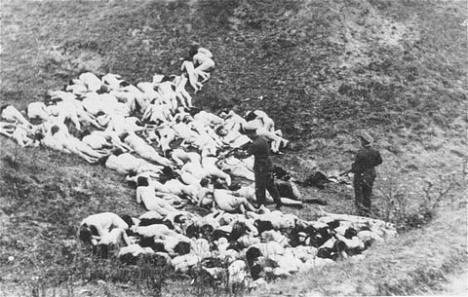

Einsatzgruppe Members killing Polish Jews

Himmler and Heydrich were sensitive to the perception of the Army and resented the fact that the Army believed them to be responsible for actions that they were carrying out under the direction and order of Hitler and that their troops were “undisciplined gangs of murderers.”[101] After the establishment of the Government General led by Hans Frank there was conflict between the Army under Blaskowitz, the SS, Police and the Nazi administration. Blaskowitz made an “elaborate report on the atrocities of the SS,”[102] expressing concern about his “extreme alarm about illegal executions, his worries about maintaining troop discipline under those circumstances, the failure of discussions with the SD and Gestapo and their assertions that they were only following SS Orders.”[103] While it is unclear if the memorandum made it to Hitler, it is clear that Hitler did know about the protest and Blaskowitz fell into disfavor and was reassigned after a period of continued conflict with the Nazi administration. Hitler’s reaction according to his adjutant was that the Army’s leaders used “Salvation Army” methods, and their ideas “childish.”[104] Likewise General Georg von Külcher was relieved of command for protesting SS and police atrocities.[105] SS Officers convicted by Army courts-martial were given amnesty by Hitler on “4 October 1939 who two weeks later removed SS units from the jurisdiction of military courts.”[106] While the army remained, it was not longer in charge and would assist the SS and Police in combat and further atrocities. One German officer, later a conspirator in the July 20th plot, remarked in November 1939 about the killings that he “was ashamed to be German! The minority are dragging our good through the mud by murdering, looting and torching houses will bring disaster on the whole German people if we do not stop it soon…”[107]

The Army was relieved of responsibility for policing Poland which fell on the Ordungspolizei battalions and Gendarmerie. These units would wreak their own devastation on Poland in the coming months and years.[108] Poland would also be the first Nazi driven shift in population to exploit the newly won Lebensraum as Poles were driven into the newly formed Government General and ethnic Germans moved into previously Polish occupied territories. By 1941 over 1,200,000 Poles and 300,000 Jews had been expelled and 497,000 ethnic Germans brought into provinces lost in 1919.[109] Prior to the war about 3.3 million Jews lived in Poland. After the war 50-70,000 were found to have survived in Poland, the Polish Army and camps in Germany. A further 180,000 were repatriated from the Soviet Union.[110]

Russia

The Nazi war against Russia was the penultimate test of Hitler’s ideology. Planning began after 21 July, when Hitler made “his intentions plain” and “von Brauchitsch set his planners to work.”[111] Detailed preparations began in the winter of 1940-41 following the Luftwaffe’s failure against Britain and postponement of Operation Sea Lion. Hitler intended to “crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign which was to begin no later than March 15, 1941, and before the end of the war with England.”[112] Keitel noted the final decision came in “early December 1940” and from then he had “no doubt whatsoever that only some unforeseen circumstance could possibly alter his decision to attack.”[113] The plan focused on the destruction of “the Red Army rather than on any specific terrain or political objective,”[114] although these objectives would arise in later planning and in the campaign. Hitler stated: “What matters is that Bolshevism must be exterminated. In case of necessity, we shall renew our advance whenever a new center of resistance is formed. Moscow as the center of doctrine must disappear from the earth’s center….”[115]

Besides preparations aimed at the destruction of the Red Army and overthrow of the Soviet State, the “war against the Soviet Union was more openly ideological from the start.”[116] Hitler set the stage on March 3rd 1941: “the forthcoming campaign is more than a mere armed conflict; it is a collision between two different ideologies…this war will not be ended merely by the defeat of the enemy armed forces” and that “the Jewish-Bolshevist intelligentsia must be eliminated….”[117] Hitler noted that “this is a task so difficult that it cannot be entrusted to the Army.”[118] Reichskommissars would be appointed in the conquered areas, but since normal civilian powers would be insufficient to eliminate the Bolshevists, that it “might be necessary “to establish organs of the Reichsführer SS alongside the army’s Secret Field Police, even in the operational areas….”[119] The “primary task was to liquidate “all Bolshevist leaders or commissars” if possible while still in the operations zones,”[120] yet the orders did not contain “a syllable that in practice every Jew would be handed over to the extermination machine.”[121] This was followed on 13 March by an agreement between the Army represented by General Wagner and the SS, which stated in part that “the Reichsführer SS has been given by the Führer special tasks within the operations zone of the Army…to settle the conflict between two opposing political systems.”[122] Likewise the agreement dictated that Himmler would “act independently and on his own responsibility” while ensuring that “military operations are not affected by measures necessary to carry out his task.”[123] A further instruction of 26 March issued by Wagner gave the Army’s agreement to the use of the Einsatzgrüppen in the operations zone, specifying coordination between them and army authorities in the operational zone and communications zones to the rear. Cooperation was based on the “principals for co-operation between the State Secret Police and the Field Security organization of the Wehrmacht agreed with the Security branch of the War Ministry on 1 January 1937.”[124]

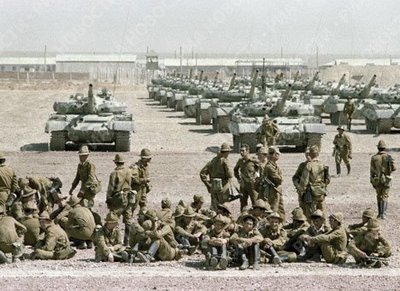

Police Battalion in the Soviet Union

The most significant act for the Army in this was the Commissar Order, sometimes known as the “Criminal Order” which was used war as evidence at Nuremberg as against Keitel and the High Command of the Wehrmacht. The order specified the killing of Soviet Political Commissars attached to the Red Army and as “they were not prisoners of war” and another order specified that “in the event that a German soldier committed against civilians or prisoners, disciplinary action was optional….”[125] The order noted regarding political commissars that “in this struggle consideration and respect for international law with regard to these elements is wrong.” [126] The “Guidelines for the Conduct of Troops in Russia” issued on May 19, 1941 called for “ruthless and vigorous measures against Bolshevist inciters, saboteurs [and] Jews.”[127]

Shortly before the order was issued, Hitler previewed it to the generals saying that the war in Russia “cannot be conducted in a knightly fashion” and that it would have to be waged with “unprecedented, unmerciful and unrelenting harshness…”[128] and that they would have to “dispense with all of their outdated and traditional ideas about chivalry and the generally accepted rules of warfare: the Bolsheviks had long since dispensed with them.”[129] He explained that his orders were beyond their comprehension stating “I cannot and will not change my orders and I insist that that they be carried out with unquestioning and unconditional obedience.”[130]

Himmler visiting POW Camp holding Red Army Prisoners, most would die in German Captivity

Hitler’s speech was protested by some according to Von Brauchitsch,[131] who refused to protest to Hitler but issued an order “threatening dire penalties for excesses against civilians and prisoners of war” which he maintained at Nurnberg “was sufficient to nullify the Commissar Order.”[132] Yet Von Brauchitsch would tell commanders to “proceed with the necessary hardness.”[133] Warlimont noted that Von Bock, who would “later emerge as an opponent of the Commissar Order…makes no special comment on the meeting or the restricted conference that followed.” [134] Keitel said that he “stubbornly contested” the clause “relating to the authority of the SS-Reichsführer… in the rearward operational areas.”[135] Keitel blamed the Army High Command, but the order came out with his signature on behalf of Hitler, which was key evidence against him at Nuremberg. He stated that “there was never any possibility of justifying them in retrospect by circumstances obtaining in the Russian campaign.”[136] Some commanders refused to publish the orders and “insisted that the Wehrmacht never implemented such policies…” blaming them instead on the SS. One writer states “such protests were undoubtedly sincere, but in practice German soldiers were far from innocent. The senior professional officers were often out of touch with their subordinates.”[137] The orders were a “license to kill, although not a great departure from German military traditions….”[138] The effect was terrifying, for in a sense the Einsatzgruppen, “could commit ever crime known to God and man, so long as they were a mile or two away from the firing line.”[139] Security Divisions were “instructed to give material and logistical support to…units of the Einsatzgruppen.”[140] Even worse, army units in rear areas “could be called on to assist Himmler’s SS police leaders.”[141]

SS Brigadefuhrer Otto Ohlendorf Commander of Einstazgruppe D

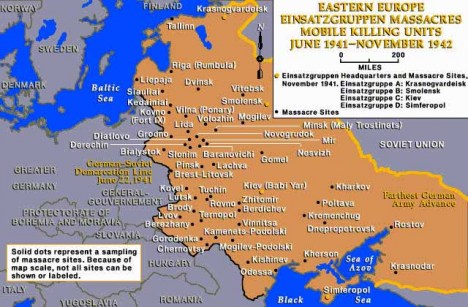

The SS formed four Einsatzgruppen composed of SD, Waffen-SS and Police troops designated A-D with “A” being assigned to Army Group North, B to Army Group Center, C to Army Group South and “D” to 11th Army. They were not standardized in manpower or equipment, the largest unit being A in the North at 990 personnel[142] and D with only 550.[143] These units had SS, SD or Police commanders. Additionally nine Ordnungspolizei battalions were initially assigned to the invasion forces.[144] The police contingent would grow over time so that by 1943, these units would be grouped under regiments and number about 180,000 men assisted by 301,000 auxiliaries.[145] These units would act in concert with 9 Army Security Divisions which handled rear area security.[146] Himmler initially did not reveal their intent and planned use to Einsatzgruppen commanders, only speaking of a “heavy task…to “secure and pacify” the Russian area using Sicherheitspolizei and SD methods.”[147] Understanding the effect of these operations, Himmler would state that “in many cases it is considerably easier to lead a company in battle than to command a company responsible to…carry out executions, to deport people…to be always consistent, always uncompromising-that is in many cases far, far harder.”[148]

Nazi actions are well documented; the Einsatzgruppen, Police, Army and locally recruited Schutzmannschaft battalions[149] ruthlessly exterminated Jews and others in the operational area. No sooner had an Einsatzgruppe unit entered a city, a “deadly stranglehold” would grip the “Jewish inhabitants claiming thousands and thousands of victims day by day and hour by hour.”[150] Non-Jewish Russians were encouraged to conduct programs which Heydrich noted “had to be encouraged.”[151] Einsatzgruppen D report 153 noted: “During period covered by this report 3,176 Jews, 85 Partisans, 12 looters, 122 Communist functionaries shot. Total 79,276.”[152] By the spring of 1942 Einsatzgruppe A had claimed “more than 270,000 victims, the overwhelming majority of whom were Jewish.”[153] The total killed for all groups then was 518,388 people, mostly Jews.[154] Germany’s Romanian ally acted against Jews in Odessa as well; “on 23 October 1941 19,000 Jews were shot near the harbor… probably 200,000 Jews perished either at Romanian hands or after being turned over by the Romanians to the Germans.”[155]

Operations against Jews were often called anti-partisan operations. Himmler referred to Einsatzgruppen as “anti-Partisan formations[156] while Wehrmacht Security divisions “murdered countless Soviet civilians and burned Russian settlements to the ground under the pretext of subduing partisan resistance.”[157] The attitude in 1941-1942 was that “’all Jews are partisans and all partisans are Jews.” From 1943, all armed resistance was “banditry” and all Jews irrespective of circumstances were treated as “bandits.””[158] The commander of the 221st Security Division endeavored to persuade his “subordinate units that the Jews were carriers of Bolshevik contamination and, therefore, the ultimate source of any sabotage or difficulty the division faced.”[159] The extermination of the Jews and partisan war were closely intertwined with the Reich’s economic policies designed to exploit the natural resources of the Russia. This included the “hunger plan” which German authorities seemed to imagine that “millionfold starvation could be induced by requisitioning off all available grain and “shutting off” the cities.”[160] Hitler told Halder that in 1941 that he “intended to level Moscow and Leningrad, to make them uninhabitable, so there would be no need to feed their populations during the winter.”[161] Economic officials held life and death power over villages. Those that met agricultural quotas were “likely to be spared annihilation and evacuation…the culmination of this process, during 1943, would be the widespread creation of “dead zones.””[162] All told the German killed nearly 1.5 million Russian Jews.[163] By 1942, 2 million Soviet POW’s were killed. 600,000 shot outright, 140,000 by the Einsatzkommandos.[164] All told 3.3 million Soviet POWs died in German captivity through starvation, disease and exposure,[165] are included in a total of over 10 million Red Army Combat deaths.[166] Bracher notes: “The reality and irreality of the National Socialism were given their most terrible expression in the extermination of the Jews.”[167]

SS Gruppenfuhrer Arthur Nebe: “I have looked after so many criminals and now I have become one myself.”

Himmler and others continued to use euphemistic language to describe their efforts talking in terms of “Jewish resettlement.”[168] Terms such as special actions, special treatment, execution activity, cleansing and resettlement were used in place of the word murder.[169] At the same time these operations led to problems in the ranks, one SS trooper observed: “deterioration in morale among his own men who had to be issued increasing rations of vodka to carry out their killing orders.”[170] Even commanders were affected, Nebe would say “I have looked after so many criminals and now I have become one myself.”[171] A fellow conspirator would describe him as a “shadow of his former self, nerves on edge and depressed.”[172] Erich Bach-Zelewski, who led the SS anti-partisan efforts would suffer a nervous breakdown which included “hallucinations connected to the shootings of Jews” which hospitalized him in 1942.[173] Himmler would state in October 1943 that “to have gone through” the elimination of the Jews had “and remained decent, that has made us tough. This is an unwritten, never to be written, glorious page in our history.”[174]

Conclusion

The German war against Poland and Russia was heavily dependent on the racist ideology of Adolf Hitler. He was the true spirit behind the atrocities committed by his nation as one noted in Russia: “Here too the Führer is the moving spirit of a radical solution in both word and deed.”[175] He saw the partisan war as “the chance to stamp out everything that stands against us.”[176] Belief in Germany’s right to Lebensraum the superiority of the German Volk and necessity to settle the Jewish problem provided a fertile ground for Hitler’s plans. German military doctrines, especially those of anti-partisan and total warfare abetted Hitler’s goals.

Einsatzgruppen Trial at Nuremberg

It is quite clear that many in the Wehrmacht were in agreement with Hitler’s ideology of racial-war. Prepared by cultural prejudice and long traditions of thought, the “Prussian and in later German military must be regarded as a significant part of the ideological background of the Second World War.”[177] General Reichenau’s orders to his troops are revealing: “The most important goal of the campaign against Jewish-Bolshevism is the complete destruction of its grip on power and the elimination of the Asian influence from our European cultural sphere.”[178] Von Rundstedt appeared to agree with Reichenau to “use the partisan threat as excuse for persecuting Jews, so long as the dirty work was largely left to SS Einsatzgruppen.”[179] The Army command…on the whole acquiesced in the extermination of the Jews, or at least closed its eyes to what was happening.”[180] Even if the Generals had been more forceful in their opposition, they would have been opposed by the highly Nazified youth that made up the bulk of their Army, especially junior officers. SS leaders fanatically executed Hitler’s policies aided by the civil administration. Genocide was to bring the Reich “long term economic gains and trading advantages” and was seen as a way of “financing the war debt without burdening the German taxpayer.”[181] Some individuals attempted to resist the most brutal aspects of the Nazi campaign against the Jews. Some like Wilhelm Kube, Reichskommissar for White Russia and a virulent anti-Semite was shocked at the murders of the Jews calling them “unworthy of the German cause and damaging to the German reputation” and would later attempt to spare Jews by employing them in war industries, would be “defeated by Himmler’s zealots.”[182] Army officers who objected like Blaskowitz and Külcher were relieved, or like Von Leeb, told by Hitler to “in so many words told to mind his own business.” Leeb stated: “the only thing to do is to hold oneself at a distance.”[183] Rommel knew of crimes through Blaskowitz but blamed the crimes “on Hitler’s subordinates, not Hitler himself.”[184]

Hitler’s ideology permeated German military campaigns and administration of the areas conquered by his armies. No branch of the German military, police or civil administration in occupied Poland or Russia was exempt guiltless in the crimes committed by the Nazi regime. It is a chilling warning of the consequences awaiting any nation that allows it to become caught up in hate-filled political, racial or even religious ideologies which dehumanizes opponents and of the tragedy that awaits them and the world. In Germany the internal and external checks that govern the moral behavior of the nation and individuals failed. Caught up in the Nazi system, the Germans, especially the police and military abandoned the norms of international law, morality and decency, banally committing crimes which still reverberate today and which are seen in the ethnic cleansing actions in the former Yugoslavia and other nations.

Bibliography

Aly, Gotz and Heim, Susanne. Architects of Annihilation: Auschwitz and the Logic of Destruction Phoenix Paperbacks, London, 2003, originally published as Vordenker der Vernichtung, Hoffman und Campe, Germany 1991, English translation by Allan Blunden. First published in Great Britain Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 2002

Arendt, Hannah, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Revised and Enlarged Edition. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, England and New York, NY 1965. Originally published by Viking Press, New York, NY 1963

Blood, Philip. Hitler’s Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Occupation of Europe. Potomoac Books Inc. Washington, DC 2008

Bracher, Karl Dietrich. The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism. Translated by Jean Steinberg, Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York, NY 1979. Originally Published under the title Die Deutsche Diktatur: Entstehung, Struktur,Folgen des Nationalsocialismus. Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch. Koln and Berlin, 1969

Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Harper Perennial Books, New York, New York 1993 reissued 1996.

Burleigh, Michael and Wippermann, Wolfgang. The Racial State: Germany 1933-1945 Cambridge University Press, New York NY and Cambridge UK 1991

Condell, Bruce and Zabecki, David T. Editors. On the German Art of War: Truppenführung , Lynn Rienner Publishers, Boulder CO and London 2001

Craig, Gordon A. The Politics of the Prussian Army 1640-1945. Oxford University Press, London and New York, 1955

Davidowicz, Lucy S. The War Against the Jews 1933-1945 Bantam Books, New York, NY 1986.

Di Nardo, Richard L. Germany and the Axis Powers: From Coalition to Collapse. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 2005

Erickson, John. The Road to Berlin. Cassel Military Paperbacks, London, 2003. First Published by Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1983

Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich Penguin Books, New York 2004. First published by Allen Lane 2003

Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich in Power 1933-1939. Penguin Press, New York, NY 2005

Ferguson, Niall. The War of the Worlds: Twentieth Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. The Penguin Press, New York, 2006

Fest, Joachim, Hitler. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, San Diego, New York, London, 1974. German Edition by Verlag Ullstein 1973

Fraser, David. Knight’s Cross: A Life of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel Harper Perennial, New York 1995, first published by Harper Collins in Britain, 1993

Friedlander, Saul Nazi Germany and the Jews 1939-1945: The Years of Extermination. Harper Perennial, New York, NY 2007

Fritz, Stephen G. Frontsoldaten: The German Soldier in World War II. The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 1995

Geyer, Michael. German Strategy 1914-1945 in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Peter Paret, editor. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ. 198

Giziowski, Richard. The Enigma of General Blaskowitz. Hippocrene Books, New York 1997

Glantz, David M. and House, Jonathan. When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 1995

Goerlitz, Walter. History of the German General Staff. Translated by Brian Battershaw, Westview Press, Boulder and London, 1985. Originally published as Die Deutsche Generalstab Verlag der Frankfurter Hefte, Frankfurt am Main, 1953

Goerlitz, Walter. The Memiors of Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel: Chief of the German High Command 1938-1945. Translated by David Irving. Cooper Square Press 2000, First English Edition 1966 William Kimber and Company Ltd. German edition published by Musterschmnidt-Verlad, Gottigen 1961 .

Hitler, Adolf Mein Kampf translated by Ralph Manheim. Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, NY 1999. Houghton Mifflin Company 1943, copyright renewed 1971. Originally published in Germany by Verlag Frz. Eher Nachf. GmbH 1925

Höhne, Heinze. Canaris: Hitler’s Master Spy. Traslated by J. Maxwell Brownjohn. Cooper Square Press,

New York 1999. Originally published by C. Bertelsmann Verlag Gmbh, Munich 1976, first English edition by Doubleday and Company 1979

Höhne, Heinze. The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS. Translated by Richard Barry. Penguin Books, New York and London, 2000. First English edition published by Martin Secker and Warburg Ltd. London 1969. Originally published as Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf, Verlag Der Spiegel, Hamburg 1966.

Hughes, Daniel J. editor. Moltke on the Art of War: Selected Writings, translated by Harry Bell and Daniel J Hughes. Presidio Press, Novato CA 1993

Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Quill Publishing, New York, NY. 1979. Copyright 1948 by B.H. Liddell-Hart

Macksey, Kenneth. Why the Germans Lose at War: The Myth of German Military Superiority. Barnes and Noble Books, New York 2006, originally published by Greenhill Books, 1996

Manstein, Erich von. Forward by B.H. Liddle Hart, Introduction by Martin Blumenson. Lost victories: The War Memoirs of Hitler’s Most Brilliant General. Zenith Press, St Paul MN 2004. First Published 1955 as Verlorene Siege, English Translation 1958 by Methuen Company

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. A Touchstone Book published by Simon and Schuster, 1981, Copyright 1959 and 1960

Megargee, Geoffrey P. War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front 1941.Bowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc. Lanham, Boulder, New York. 2007

Messinger, Charles, The Last Prussian: A Biography of Field Marshal Gerd Von Rundstedt 1875-1953 Brassey’s (UK) London England 1991

Newton, Steven H. Hitler’s Commander: Field Marshal Walter Model-Hitler’s Favorite General DaCapo Press a division of Perseus Books Group, Cambridge MA 2005

Novatny, Alfred. The Good Soldier. The Aberjona Press, Bedford, PA 2003

Padfield, Peter. Himmler. MJF Books, New York. 1990

Reitlinger, Gerald. The SS: Alibi of a Nation. The Viking Press, New York, 1957. Republished by Da Capo Press, New York, NY.

Rhodes, Richard. Masters of Death: The SS Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. Vintage Books a division of Random House, New York, NY 2002

Shepherd, Ben. War in the Wild East: The German Army and Soviet Partisans. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2004

Sofsky, Wolfgang. The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp. Translated by William Templer. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ 1997. Originally published as Die Ordnung des Terros: Das Konzentrationslager. S. Fischer Verlag, GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, 1993

Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich. Collier Books, a Division of MacMillan Publishers, Inc. New York, NY 1970.

Strachan, Hew. European Armies and the Conduct of War. George, Allen and Unwin, London, UK 1983

Stein, George H. The Waffen SS 1939-1945: Hitler’s Elite Guard at War. Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London, 1966

Stern, Fritz. Gold and Iron: Bismarck, Bleichroder and Building of the German Empire. Vintage Books a division of Random House, New York 1979 First published by Alfred a Knopf 1977

Sydnor, Charles W. Soldiers of Destruction: The SS Death’s Head Division, 1933-1945. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NY 1977 Taylor, Fred, Editor and Translator. The Goebbels Diaries 1939-1941, Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth UK and New York NY 1984.

Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction Penguin Books, New York, NY, 2008. First Published by Allen Lane Books, Penguin Group, London UK, 2006

Trevor-Roper, H.R. Hitler’s Table Talk 1941-1944 with an introduction by Gerhard L Weinberg, Translated by Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens, Enigma Books, New York, NY 2000. Originally published in Great Britain by Weidenfeld & Nicholoson, London 1953.

Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-45. Translated by R.H. Berry, Presido Press, Novato CA, 1964.

Weinberg, Gerhard L. Germany Hitler and World War II . Cambridge University Press, New York, NY 1995

Weinberg, Gerhard L. Ed. Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf by Adolph Hitler. Translated by Krista Smith, Enigma Books, New York, NY 2006. Originally published as Hitlers zweites Buch, Gerhard Weinberg editor, 1961.

Weinberg, Gerhard L. Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leasers. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY 2005

Westermann, Edward B. Hitler’s Police Battalions: Enforcing Racial War in the East. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 2005

Wette, Wolfram. The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2006. Originally published as Die Wehrmacht: Feindbilder, Vernichtungskreig, Legenden. S. Fischer Verlag, GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, 2002

Wheeler-Bennett, John. The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945. St. Martin’s Press Inc. New York, NY 1954

Notes

[1] Weinberg, Gerhard L. Ed. Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf by Adolph Hitler. Translated by Krista Smith, Enigma Books, New York, NY 2006. Originally published as Hitlers zweites Buch, Gerhard Weinberg editor, 1961 p. 159

[2] Davidowicz, Lucy S. The War Against the Jews 1933-1945 Bantam Books, New York, NY 1986. p.91

[3] Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction Penguin Books, New York, NY, 2008. First Published by Allen Lane Books, Penguin Group, London UK, 2006. p.463

[4] Fest, Joachim, Hitler. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, San Diego, New York, London, 1974. German Edition by Verlag Ullstein 1973 pp. 607-608

[5] Note the actions of Cardinal Richelieu in France who worked to expand French power at the expense of other Catholic nations and the Vatican itself.

[6] In the United States the Reconstruction policies produced great resentment in the south with decidedly negative results for the newly freed slaves which lasted another 100 years, while in the Soviet Union great numbers of “opponents of Socialism” were killed, imprisoned or driven out of the county.

[7] Ibid. Tooze. The Wages of Destruction p.462

[8] Ibid. Davidowicz, The War Against the Jews pp.8-9

[9] Ibid. Davidowicz. The War Against the Jews p.12

[10] Ibid. Fest Hitler. p.47

[11] Bracher, Karl Dietrich. The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism. Translated by Jean Steinberg, Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York, NY 1979. Originally Published under the title Die Deutsche Diktatur: Entstehung, Struktur,Folgen des Nationalsocialismus. Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch. Koln and Berlin, 1969 p.93

[12] Weinberg, Gerhard L. Germany Hitler and World War II . Cambridge University Press, New York, NY 1995 p.61

[13] Ibid. Weinberg, Hitler’s Second Book p.60

[14] Friedlander, Saul Nazi Germany and the Jews 1939-1945: The Years of Extermination. Harper Perennial, New York, NY 2007 p.xviii

[15] Ibid. Friedlander, The Years of Extermination p.xvii Friedlander called this anti-Semitism “Redemptive anti-Semitism” in which “Hitler perceived his mission as a kind of crusade to redeem the world by eliminating the Jews.

[16] Megargee, Geoffrey P. War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front 1941.Bowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc. Lanham, Boulder, New York. 2007 p.4

[17] Hitler, Adolf Mein Kampf translated by Ralph Manheim. Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, NY 1999. Houghton Mifflin Company 1943, copyright renewed 1971. Originally published in Germany by Verlag Frz. Eher Nachf. GmbH 1925. p.662.

[18] Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich Penguin Books, New York 2004. First published by Allen Lane 2003 p.197

[19] Ibid. Davidowicz The War Against the Jews pp. 88-89

[20] Rhodes, Richard. Masters of Death: The SS Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. Vintage Books a division of Random House, New York, NY 2002 p.37

[21] Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich. Collier Books, a Division of MacMillan Publishers, Inc. New York, NY 1970 p.166

[22] Geyer, Michael. German Strategy 1914-1945 in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Peter Paret, editor. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ. 1986. p.582

[23] Ibid. Geyer. German Strategy p.587

[24] Strachan, Hew. European Armies and the Conduct of War. George, Allen and Unwin, London, UK 1983 p.174

[25] Goerlitz, Walter. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel: Chief of the German High Command 1938-1945. Translated by David Irving. Cooper Square Press 2000, First English Edition 1966 William Kimber and Company Ltd. German edition published by Musterschmnidt-Verlad, Gottigen 1961 p. 135

[26] Ibid. Fest, Hitler. p. 649

[27] Ibid. Megargee, War of Annihilation p.7

[28] Trevor-Roper, H.R. Hitler’s Table Talk 1941-1944 with an introduction by Gerhard L Weinberg, Translated by Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens, Enigma Books, New York, NY 2000. Originally published in Great Britain by Weidenfeld & Nicholoson, London 1953 p. 27 Goebbels notes a similar theme in his recollection of Hitler’s reasons for destroying Russia a power . See Taylor, Fred, Editor and Translator. The Goebbels Diaries 1939-1941, Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth UK and New York NY 1984 pp. 413-415.

[29] Goerlitz, Walter. History of the German General Staff.” Translated by Brian Battershaw, Westview Press, Boulder and London, 1985. Originally published as Die Deutsche Generalstab Verlag der Frankfurter Hefte, Frankfur am Main, 1953 p.390

[30] Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-45. Translated by R.H. Berry, Presido Press, Novato CA, 1964 p. 150

[31] Weinberg, Gerhard L. Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leasers. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY 2005. p. 24

[32] Aly, Gotz and Heim, Susanne. Architects of Annihilation :Auschwitz and the Logic of Destruction Phoenix Paperbacks, London, 2003, Originally published as Vordenker der Vernichtung, Hoffman und Campe, Germany 1991, English translation by Allan Blunden. First published in Great Britain Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 2002 pp. 245-246

[33] Ibid. Fest. Hitler p.649

[34] Wette, Wolfram. The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2006. Originally published as Die Wehrmacht: Feindbilder, Vernichtungskreig, Legenden. S. Fischer Verlag, GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, 2002 p.93

[35] This understanding is different than many historians who as Friedlander notes advocate something like this: “The persecution and extermination of the Jews of Europe was but a secondary consequence of major German policies pursued toward entirely different goals.” Friedlander p.xvi

[36] Ibid. Megargee. War of Annihilation p.xii

[37] Liddell-Hart, B.H. The German Generals Talk. Quill Publishing, New York, NY. 1979. Copyright 1948 by B.H. Liddell-Hart p.22

[38] It has to be noted that Liddle-Hart published this work in 1948 and was limited in the materials available, his primary sources being German officers who he viewed with sympathy because he saw them as exponents of his theory of the indirect approach.

[39] Ibid. Wette. The Wehrmacht p.224

[40] Macksey, Kenneth. Why the Germans Lose at War: The Myth of German Military Superiority. Barnes and Noble Books, New York 2006, originally published by Greenhill Books, 1996. p.139

[41] Stern, Fritz. Gold and Iron: Bismarck, Bleichroder and Building of the German Empire. Vintage Books a division of Random House, New York 1979 First published by Alfred a Knopf 1977. p.495

[42] Ibid. Stern. Gold and Iron p.494

[43] Ibid. Bracher. The German Dictatorship p.34

[44] Ibid. Bracher The German Dictatorship pp.34-35

[45] Höhne, Heinze. Canaris: Hitler’s Master Spy. Translated by J. Maxwell, Brownjohn. Cooper Square Press,

New York 1999. Originally published by C. Bertelsmann Verlag Gmbh, Munich 1976, first English edition by Doubleday and Company 1979 p. 216. Canaris would later protest the Kristalnacht to Keitel (p.334) and become convinced of the crime of the Nazis against the Jews.

[46] Ibid. Witte. The Wehrmacht p.98

[47] Ibid Witte The Wehrmacht, p.73

[48] Arendt, Hannah, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Revised and Enlarged Edition. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, England and New York, NY 1965. Originally published by Viking Press, New York, NY 1963 p.26

[49] Ibid. Megargee. War of Annihilation p.6

[50] Fritz, Stephen G. Frontsoldaten: The German Soldier in World War II. The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 1995 p.195

[51] Craig, Gordon A. The Politics of the Prussian Army 1640-1945. Oxford University Press, London and New York, 1955 p.495

[52] Novatny, Alfred. The Good Soldier. The Aberjona Press, Bedford, PA 2003 p.40

[53] Westermann, Edward B. Hitler’s Police Battalions: Enforcing Racial War in the East. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 2005 p.64 Westermann also notes the preponderance of SA men who entered the Order Police in the 1930s, a factor which helped further the politicization of that organization.

[54] Ibid. Rhodes Masters of Death p.23

[55] Ibid. Westermann Hitler’s Police Battalions p.103

[56] Sydnor, Charles W. Soldiers of Destruction: The SS Death’s Head Division, 1933-1945. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NY 1977 p. 28

[57] Shepherd, Ben. War in the Wild East: The German Army and Soviet Partisans. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2004 p.41

[58] Blood, Philip. Hitler’s Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Occupation of Europe. Potomac Books Inc. Washington, DC 2008 p.11

[59] Ibid. Shepherd. War in the Wild East p.42

[60] Ibid. Goerlitz. History of the German General Staff p.93

[61] Rothenburg, Gunther. Moltke, Schieffen, and the Doctrine of Strategic Envelopment in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Peter Paret, editor. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ. 1986 p.305

[62] Hughes, Daniel J. editor. Moltke on the Art of War: Selected Writings, translated by Harry Bell and Daniel J Hughes. Presidio Press, Novato CA 1993. p.32

[63] Ibid. Blood Hitler’s Bandit Hunters p.6 Lieber was a Prussian emigrant to the US who taught law at Columbia University.

[64] Ibid. Blood Hitler’s Bandit Hunters pp.12-13

[65] Ibid. Shepherd Wild War in the East p.42

[66] Ibid. Blood. Hitler’s Bandit Hunters pp.16-19

[67] Ibid. Blood. Hitler’s Bandit Hunters p.22

[68] Condell, Bruce and Zabecki, David T. Editors. On the German Art of War: Truppenführung , Lynn Rienner Publishers, Boulder CO and London 2001. p.172

[69] Tsouras, Peter G. Editor, Fighting in Hell: The German Ordeal on the Eastern Front The Ballantine Publishing Group, New York, 1998. First published 1995 by Greenhill Books. Pp. 142-146. It is interesting to note that Rauss does not describe any actual anti-partisan operation.

[70] Ibid. Shepherd. War in the Wild East p.45

[71] Ibid. Geyer. German Strategy p.584

[72] Ibid. Weinberg. Visions of Victory p.8

[73] Ibid. Goerlitz, History of the German General Staff p.346

[74] Höhne, Heinze. The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS. Translated by Richard Barry. Penguin Books, New York and London, 2000. First English edition published by Martin Secker and Warburg Ltd. London 1969. Originally published as Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf, Verlag Der Spiegel, Hamburg 1966 p.259

[75] Manstein, Erich von. Forward by B.H. Liddle Hart, Introduction by Martin Blumenson. Lost victories: The War Memoirs of Hitler’s Most Brilliant General. Zenith Press, St Paul MN 2004. First Published 1955 as Verlorene Siege, English Translation 1958 by Methuen Company p.29

[76] Ibid. Hohne. Canaris p.347

[77] Giziowski, Richard. The Enigma of General Blaskowitz. Hppocrene Books, New York 1997 p.119

[78] Ibid. Manstein. Lost Victories p.29

[79] Ibid. Goerlitz. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Keitel p.87

[80] Wheeler-Bennett, John. The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918-1945. St. Martin’s Press Inc. New York, NY 1954 p.448

[81] Ibid. Megargee. War of Annihilation p.13

[82] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p.297

[83] Padfield, Peter. Himmler. MJF Books, New York 1990 p.264

[84] Ibid. Megargee. War of Annihilation p.13

[85] Ibid. Westermann. Hitler’s Police Battalions p.127

[86] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p.297

[87] Ibid. Westermann. Hitler’s Police Battalions p.127

[88] Ibid. Sydnor Soldiers of Destruction p.37 These would become the nucleus of the Totenkopf Division

[89] Ibid. Giziowski Blaskowitz p.120

[90] Ibid. Witte. The Wehrmacht p.100

[91] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head pp. 297-298

[92] Ibid. Giziowski Blaskowitz p.120

[93] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p.298

[94] Ibid. Witte. The Wehrmacht p.100

[95] Newton, Steven H. Hitler’s Commander: Field Marshal Walter Model-Hitler’s Favorite General Da Capo Press a division of Perseus Books Group, Cambridge MA 2005. p.74

[96] Ibid. Giziowski. The Enigma of General Blaskowitz pp.165-166

[97] Ibid. Sydnor, Soldiers of Destruction pp. 42-43 Note SSVT is the common abbreviation for the SS Totenkopf Verbande

[98] Ibid. Goerlitz. History of the German General Staff p.359

[99] Ibid. Newton. Hitler’s Commander p.78

[100] Ibid. Witte The Wehrmacht p.102

[101] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p.298

[102] Ibid. Goerlitz. History of the German General Staff .p.359

[103] Ibid. Giziowski. The Enigma of General Blaskowitz p.173

[104] Ibid. Giziowski. The Enigma of General Blaskowitz p.173

[105] Ibid. Witte The Wehrmacht p.102

[106] Burleigh, Michael and Wippermann, Wolfgang. The Racial State: Germany 1933-1945 Cambridge University Press, New York NY and Cambridge UK 1991. p.100

[107] Ibid. Witte The Wehrmacht p.102

[108] For a good account of one of the Police Battalions see Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101mand the Final Solution in Poland by Christopher Browning Harper Perennial Publishers, San Francisco CA 1992

[109] Reitlinger, Gerald. The SS: Alibi of a Nation. The Viking Press, New York, 1957. Republished by Da Capo Press, New York, NY p.131

[110] Ibid. Davidowicz The War Against the Jews pp.395-397

[111] Ibid. Megargee. War of Annihilation p.24

[112] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett The Nemesis of Power p.511

[113] Ibid. Goerlitz. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. P.132

[114] Glantz, David M. and House, Jonathan. When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 1995 p.31

[115] Trevor-Roper, H.R. Hitler’s Table Talk 1941-1944 with an introduction by Gerhard L Weinberg, Translated by Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens, Enigma Books, New York, NY 2000. Originally published in Great Britain by Weidenfeld & Nicholoson, London 1953 p.6

[116] Ibid. Megargee. War of Annihilation p.10 More openly ideological as compared to Poland.

[117] Ibid. Warlimont. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters p.150

[118] Ibid. Warlimont. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters p.151

[119] Ibid. Reitlinger, The SS p.175

[120] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 354

[121] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 354 Again another deception.

[122] Ibid. Warlimont. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters p.153

[123] Ibid. Warlimont. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters p.153

[124] Ibid. Warlimont. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters pp. 158-159

[125] Ibid. Glantz and House. When Titans Clashed p.56

[126] Ibid. Davidowicz. The War Against the Jews p.123

[127] Ferguson, Niall. The War of the Worlds: Twentieth Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. The Penguin Press, New York, 2006 p.442

[128] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett. Nemesis of Power p.513

[129] Ibid. Goerlitz. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Keitel p.135

[130] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett. Nemesis of Power p.513

[131] Ibid. Wheeler-Bennett Nemesis of Power p.513 and footnote. He cites the three Army Group commanders, Leeb, Rundstedt and Bock. However Von Rundstedt’s biographer notes that “no evidence exists as to what Von Rundstedt’s to this was at the time.” Messenger, Charles, The Last Prussian: A Biography of Field Marshal Gerd Von Rundstedt 1875-1953 Brassey’s (UK) London England 1991. p.134

[132] Ibid. Reitlinger, The SS p.176

[133] Ibid. Megargee. War of Annihilation p.33

[134] Ibid. Warlimont. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters p.162

[135] Ibid. Goerlitz. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Keitel p.136

[136] Ibid. Goerlitz. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Keitel pp.136-137

[137] Ibid. Glantz and House. When Titans Clashed p.56

[138] Ibid. Blood. Hitler’s Bandit Hunters p.52

[139] Ibid. Reitlinger The SS p. 177

[140] Ibid. Shepherd. War in the Wild East p.54

[141] Ibid. Reitlinger The SS p. 177

[142] Ibid. Rhodes Masters of Death pp.12-13

[143] Ibid. Westermann. Hitler’s Police Battalions p.167

[144] Ibid. Westermann. Hitler’s Police Battalions p.164

[145] Ibid. Blood Hitler’s Bandit Hunters p.141

[146] Ibid. Shepherd Wild War in the East p.48. Shepherd notes the deficiencies of these units in terms of organization, manpower and equipment which he calls “far short of the yardstick of military excellence with which the Wehrmacht is so widely associated.

[147] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 356 Only one of the Einsatzgruppen commanding officers was a volunteer, Arthur Nebe who was involved in the conspiracy to kill Hitler. It is believed by many that Nebe volunteered to earn the clasp to the Iron Cross to curry favor with Heydrich and that initially “Nebe certainly did not know that “employment in the east” was synonymous with the greatest mass murder in history.

[148] Ibid. Bracher. The German Dictatorship p.422

[149] Ibid. Blood Hitler’s Bandit Hunters p.55

[150] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 360

[151] Ibid. Friedlander The Years of Extermination p.207

[152] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 360

[153] Ibid. Tooze The Wages of Destruction p.481

[154] Ibid. Ferguson. The War of the World p.446

[155] Di Nardo, Richard L. Germany and the Axis Powers: From Coalition to Collapse. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 2005 p.133 The Hungarians would also engage in ant-Jewish operations. Only the Italian army would not conduct operations against the Jews.

[156] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 369

[157] Ibid. Wette The Wehrmacht p.127

[158] Ibid. Blood. Hitler’s Bandit Hunters p.117

[159] Ibid. Shepherd. War in the Wild East pp.90-91

[160] Ibid. Tooze The Wages of Destruction p.481

[161] Ibid. Magargee. War of Annihilation p.64

[162] Ibid. Shepherd. War in the Wild East pp.127-128

[163] Ibid. Davidowicz The War Against the Jews from the table on page 403. This included 228,000 from the Baltic republics (90%) 245,000 from White Russia (65%) 900,000 from the Ukraine (60%) and 107,000 from Russia proper (11%)

[164] Ibid. Rhodes. Masters of Death p.241

[165] Ibid. Glantz and House When Titans Clashed p.57

[166] Ibid. Glantz and House. When Titans Clashed table on p.292

[167] Ibid. Bracher. The German Dictatorship p.431

[168] Ibid. Bracher. The German Dictatorship p.430

[169] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 367

[170] Ibid. Rhodes. Masters of Death p.225

[171] Ibid. Rhodes Masters of Death p.225

[172] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 363

[173] Ibid. Höhne The Order of the Death’s Head p. 363

[174] Ibid. Bracher. The German Dictatorship p.423

[175] Ibid. Bracher. The German Dictatorship p.430

[176] Ibid. Megargee War of Annihilation p.65

[177] Ibid. Wette. The Wehrmacht p.293

[178] Ibid. Wette. The Wehrmacht p.97

[179] Messenger, Charles. The Last Prussian A Biography of Field Marshal Gerd Von Rundstedt 1875-1953 Brassey’s London, 1991 p148

[180] Ibid. Bracher The German Dictatorship pp.430-431

[181] Ibid. Aly and Heim Architects of Annihilation p.242

[182] Ibid. Padfield Himmler pp.341-342

[183] Ibid. Megargee War of Annihilation p.97

[184] Fraser, David. Knight’s Cross: A Life of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel Harper Perennial, New York 1995, first published by Harper Collins in Britain, 1993. p.536