USS Quincy under Attack off Savo Island

[Note: Updated 15 August 2020 in regard to the erroneous account of Rear Admiral Samuel Elliot Morrison regarding Australian Scout Planes which was repeated in every American history of the battle until it was refuted by the U.S. Navy’s Historical Branch in 2014.]

Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

Tonight I am going back to my World War II vault and reposting an older article about the Battle Of Savo Island off Guadalcanal. It was the most lopsided defeat in modern American Naval history. It happened a long time ago and in an age where the United States Navy has not lost a ship in combat, other to mines since August 6th 1945.

Since the latter part of the Cold War when the Soviets Red Navy under Admiral Sergey Gorshkov began to become true threat. In fact it became a threat to our plans to defend Western Europe through its submarine force, its growing surface force, and its integration with Soviet Naval Aviation Tu-16 Badger and Tu-22 Backfire bombers armed with conventional or nuclear air to ship cruise missiles, or Tu-16s equipped for EW, ASW, or Reconnaissance missions. One possible scenario was played out in Tom Clancy’s Cold War thriller, “Red Storm Rising.” In a successful attack by Badgers and Backfires the USS Nimitz was heavily damaged and knocked out of action by two missile hits, the French Carrier Foch was sunk by multiple hits, USS Saipan LHA-2 with over 2500 Marines and Sailors embarked was blown up and sank with only 200 survivors, in addition the USS Ticonderoga CG-47 heavily damaged and put out of action. The Soviets used deception and a saturation attack by anti-ship missiles that overwhelmed our defenses. I was an Army officer serving in Germany when the book was published and it was frightening, because even though the United States and our NATO allies prevailed, it was a great cost, and had it occurred my unit would have been likely chewed to pieces in the Battle for Germany.

However, since the end of the Cold War we got lazy, with the fall of the Soviet Union we reduced the size of our fleet by massive numbers and then got involved in a series of small wars which wore out ships, and aircraft faster than programmed, and resulted in the early decommissioning of 30 ships, and reduction of 30,000 sailors to fund the war in Iraq. These wars caused additional funding shortages, which were made much worse by the Republican shutdown of Congress which resulted in great sequester of spending that impacted every government agency.

This included a military that was still at war and a massive backlog of maintenance, and replacement of ships. This was compounded by the costly Zumwalt Class “destroyers” which became so that only three of twelve were built, and now the Navy is trying to figure out a mission for them. Likewise, the Littoral Combat Ship or LCS program was promoted as an inexpensive heavily armed and versatile “street fighter.” Unfortunately it came in massively over budget, under armed, incapable of operating with or protecting Carrier Strike Groups, or Expeditionary Strike Groups, and plagued by numerous and often embarrassing maintenance failures. Like the Zumwalt’s the Navy is trying to figure out what to due with them. The USS Gerald Ford Class carriers, the designed replacements for the Nimitz Class are so expensive and plagued with ongoing issues of their new and innovative systems are so bad that the Navy is openly questioning if enough can be built to replace the Nimitz Class Ships. The Ford, though commissioned in 2018, has not deployed and probably will not deploy until 2022.

It seems that we forgotten to remember that should a war break out with a near-peer competitor, like the Chinese Communists or the Russians in waterers where they can gain local superiority, or even regional powers such as Iran which could use asymmetric means of large numbers of small missile equipped ships and attack boats, costal submarines, and land based anti-ship missiles in “swarm attacks” to overwhelm technologically superior American ships in confined waters. We have come close to losing major ships, the cruiser USS Princeton and Helicopter Carrier USS Tripoli, to very primitive moored mines during the First Gulf War, the USS Ruben James to a mine during the tanker wars, and the USS Stark which was hit by Iraqi Exocet anti-ship missiles in 1987. Likewise we have come close to losing the Guided Missile destroyers USS Cole (Terrorist attack), USS John S. McCain and USS Fitzgerald (avoidable collisions with merchant ships), and finally, and perhaps the most disturbing, the fire aboard the USS Bonhomme Richard last month that was so catastrophic that it is quite likely the ship will ever be repaired to her former mission requirements, and her replacement costs will be more than we can afford.

I won’t go into the destruction of the relationships that the Trump administration has caused with the nation’s whose navies we depend on to help us sustain overseas operations in Europe and the Pacific, nor the dearth of shipbuilding, repair, and dry-docking facilities in the United States needed to produce and repair warships in peace, and even more importantly in war.

We have been lucky. We won’t be as lucky in a real live shootout today. Ships will be lost, damaged, and sailors will die. Compounding the problem for the United States is that years of focus on Iraq and Afghanistan, failed experiments with reducing crew size (smart-ship), reductions in numbers of ships and sailors to satisfy the budgets needs to the unnecessary invasion of Iraq, and the stress put on remaining ships and aircraft have worn us down. Readiness rates remain down, and we no longer have the shipbuilding and repair facilities to replace losses and repair damaged ships, especially in a war with China. There currently are no answers to this.

That is why instead of commenting on today’s news I write about the worst defeat suffered by the U.S. Navy in the modern era, which I label from World War II to the present, and hope, maybe beyond hope that it will not happen again, but my guess is that those chances are 50/50, but that there is only a ten percent chance of that.

After Savo Island the U.S. Navy continued to lose carriers, cruisers, and destroyers at an alarming rate, but the resources of the nation had been fully mobilized to replace the losses tenfold, and repair the damaged ships and return them to action. That could not happen today.

Sadly, I think that my introduction to this article may be longer than the article itself. But such are the dangers we face today.

Until tomorrow,

Peace,

Padre Steve+

On August 8th 1942 the U.S. Task Force supporting the invasion of Guadalcanal was tired. The crews of the ships had been in continuous combat operations conducting naval gunfire support missions, fending off numerous Japanese air attacks and guarding against submarine attacks for two days. The force commanded by Admiral Richmond K. Turner was still unloading materials, equipment and supplies needed by the men of the 1st Marine Division who they had put ashore on the morning of the seventh.

On the afternoon of the eighth Turner was informed by Admiral Frank “Jack” Fletcher that he was pulling his carrier task force out of action. Fletcher alleged that he did not have enough fighter aircraft (79 remaining of an original 98) and as low on fuel. The carriers had only been in action 36 hours and Fletcher’s reasons for withdraw were flimsy. Fletcher pulled out and left Turner and his subordinate commanders the responsibility of remaining in the area without air support with the transports still unloaded, and full of badly needed supplies and equipment.

Admiral Gunichi Mikawa

As the American drama played out, the Japanese moved forces into position to strike the Americans. Admiral Gunichi Mikawa commander of the 8th Fleet and Outer South Seas Force based at Rabaul New Britain quickly assembled a force of 6 heavy cruisers, the 14,000 ton Atago Class Chokai, and the four smaller ships of the Kako Class, the Aoba, Kako, Kinugasa and Furutaka, the light cruisers Yubariand Tenryu and the destroyer Yunagi. Mikawa raised his flag aboard Chokai and the force sped down “the slot” which ran the length of the of the Solomon’s chain mid day on the seventh.

The Americans had warning of their coming. The first sighting was by B-17s before the Japanese forces had reached Rabaul. The second was the elderly U.S. Navy submarine S-38 at 2000 on the 7th when they were 550 miles away not far from Rabaul. This report was discounted because it would not be unusual to find a number of fleet units steaming near a major naval base and fleet headquarters. The last which should have alerted the allies was a sighting by a Royal Australian Air Force patrol aircraft on the morning of the 8th. The crew made numerous attempts to report this, but the common story, which first began with Samuel Elliott Morrison’s account of the battle in his 15 volume History of U.S. Navy Operations in World War Two falsely said that the Australian flight crew made no effort to report the information and flew back to their base, and had tea. American Naval historians writing about the battle have reported this as fact ever since, including me in previous iterations of this article, which I corrected in this article today (8/15/2020). The crew attempted to report it, and their report was even intercepted and reported by the Japanese. Not knowing if their report had been received they made an early return to base and made their report in person to the intelligence officer. This was first reported in 2013, and in 2014, the Chief of the U.S. Navy History Department collaborated the account sole survivor of that aircrew. Hopefully future historians of the battle will do the same. That being said no information was passed to Admiral Turner at Guadalcanal.

The fact is that the allied forces had warning and chose to minimize the threat. Their actions in the following hours displayed an extreme amount of complacency and and failures to take a more active role in preventing any possible Japanese. The American and Australian cruisers all had floatplanes which could have deployed despite a lack of experience in night operations, as the Japanese did so well.

USS Astoria on August 8th off Guadalcanal and USS Chicago (below)

Allied Dispositions

During the early evening Turner recalled Crutchley to his flagship for consultations of what to do regarding Fletcher’s retreat. Crutchley came over in his flagship the Australia denuding the southern force of its commander as well as one of its three heavy cruisers. He left the commanding officer of Chicago Captain Howard D. Bode in tactical command but Bode did not have his ship take the lead position in the patrol assuming Crutchley would return bymidnight.

USS Vincennes (above) and USS Quincy (below)

HMAS Canberra

Mikawa launched float planes to scout the locations of the American ships and to provide illumination once the battle began. Some of these aircraft were spotted but no alert measures were taken as many assumed the Japanese to be friendly aircraft. Many commanding officers were asleep or resting away from the bridge of their ships, lookouts were tired and not expecting the Japanese and Condition Two was set in order to provide some of the tired crews a chance to rest.

Light Cruiser Yubari illuminating American cruisers at Savo Island

Admiral Mikawa now new the Allied disposition and ordered his ships to battle stations at 0045. At 004 he sighted and passed astern of USS Blue the southern picket which also failed to detect the Japanese force. Mikawa assumed that the destroyer might have reported his presence, briefly turned north but turned back to his original course when a lookout allegedly spotted a destroyer to his northeast. He gave the order to attack at 0132 and promptly spotted the American destroyer USS Jarvis which had been heavily damaged and without radio communications was making her way toAustralia for repair and passed her after some ships fired torpedoes and raced toward the southern force at 26 knots. With the southern force just a few miles away Mikawa ordered his ships to commence firing at 0136 and at 0138 torpedoes had been launched.

Mikawa’s lookouts spotted the northern group at 0144 and changed course. The maneuver was badly executed and left the Japanese in two columns as they swiftly closed on the Americans. Mikawa’s flagship Chokai launched torpedoes at 0148 and Astoria the cruiser closest to the Japanese set general quarters at 0145 and at 0150 the Japanese illuminated her with searchlights and opened fire. Astoria under the direction of her gunnery officer returned fire at 0152 ½ just before her Captain came to the bridge unaware of the situation. He ordered a cease fire until he could ascertain who he was firing at assuming the Japanese to be friendly ships. He delayed 2 minutes and ordered fires commenced at 0154 but the delay was fatal. Astoria had opened fire on the Chokai which then had time to get the range on the American cruiser and hit her with an 8” salvo which caused fires which provided the other Japanese ships an aiming point.

Japanese artist depiction of attack on US Navy Cruisers at Savo Island

Astoria was left burning and heavily damaged barely maintaining headway but attempted to fight on scoring a hit on Chokai’s forward turret even as the Japanese opened up on the next cruiser in line the USS Quincy. Quincy caught between the two Japanese columns. Aoba illuminated her with her searchlight and Japanese forces opened fire. The gunnery officer order Quincy to return fire getting two salvos off before her skipper Captain Samuel Moore came to the bridge, briefly ordered a cease fire assuming that he was firing on Americans and turned on his running lights. Quincy was ripped by salvo after salvo which killed Captain Moore and nearly everyone in the pilothouse just as a torpedo ripped into her engineering spaces turning them into a sealed death trap forcing the engineer to shut down the engines. Burning like a Roman candle Quincy was doomed she was ordered abandoned and capsized and sank at 0235. However Quincy did not die in vain, at 0205 two of her 8” shells hit Chokai causing enough damage the Admiral’s chart room that Mikawa would order a withdraw at 0220 which spared the now defenseless American transports.

Vincennes, the lead ship and flagship was next in the line of death. Captain Reifkohl order General Quarters sounded not long after the Japanese illuminated the southern group. At 0150 Vincennes was lit up by the searchlights of three Japanese ships which opened fire on her. Vincennes returned fire at 0153 hitting Kinugasa before she was hit starting fires on her scout planes mounted on their catapults. The Japanese mauled Vincennes, three possibly four torpedoes ripped into her as shells put ever gun out of action. At 0215 she was left burning and sinking by the Japanese who soon withdrew from the action. Ordered abandoned she sank at 0250.

HMAS Canberra being evacuated by the Patterson and Blue

Canberra struggled against the odds but was abandoned and was sent to the bottom by an American torpedo at 0800. Astoria also struggled for life but the damage was too great and she was abandoned sinking at 1215. Mikawa withdrew up the sound but on his return the Heavy Cruiser Kako 70 miles from home was sunk by torpedoes from the American submarine S-44 sinking in 5 minutes.

The Americans and Australians lost 4 Heavy Cruisers sunk and one heavily damaged. Two destroyers were also damaged. Casualties were heavy; Quincy lost 389 men killed, Vincennes, 342, Astoria, 235, Canberra, 85, Ralph Talbot, 14, Patterson, 10, and Chicago, 2.

It was an unmitigated disaster, an allied force destroyed in less than 30 minutes time. Boards of inquiry were held and Captain Bode hearing that he shouldered much blame killed himself in 1943.

Admiral Turner gave an honest assessment of the defeat:

“The Navy was still obsessed with a strong feeling of technical and mental superiority over the enemy. In spite of ample evidence as to enemy capabilities, most of our officers and men despised the enemy and felt themselves sure victors in all encounters under any circumstances. The net result of all this was a fatal lethargy of mind which induced a confidence without readiness, and a routine acceptance of outworn peacetime standards of conduct. I believe that this psychological factor, as a cause of our defeat, was even more important than the element of surprise”

Wrecks of the USS Quincy, Astoria, Vincennes, and HMAS Canberra

It was a rude awakening to a Navy which had believed that technical advances would give it victory and which in the words of Admiral Ernest King was not yet “sufficiently battle minded.” It was the first of many equally bloody battles in the waters around Guadalcanal which in the coming campaign became known as Ironbottom Sound.

Aircraft over Saratoga

Aircraft over Saratoga USS Langley CV-1 The “Covered Wagon”

USS Langley CV-1 The “Covered Wagon”  Langley after conversion to AV-3

Langley after conversion to AV-3 USS Lexington CV-2

USS Lexington CV-2 USS Saratoga CV-3

USS Saratoga CV-3 Lexington Burning and Sinking

Lexington Burning and Sinking Saratoga 1945

Saratoga 1945 Saratoga September 1943

Saratoga September 1943 Saratoga burning after Kamikaze hits in 1945

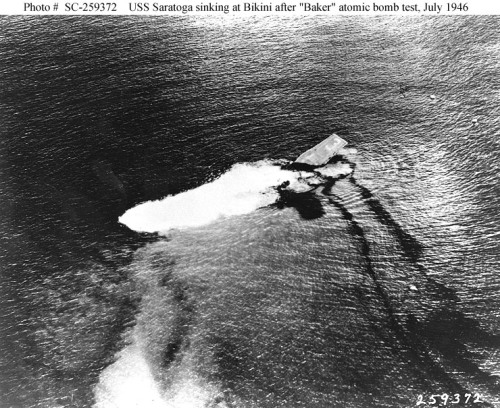

Saratoga burning after Kamikaze hits in 1945 The End of an Era- Saratoga goes down at Bikini

The End of an Era- Saratoga goes down at Bikini