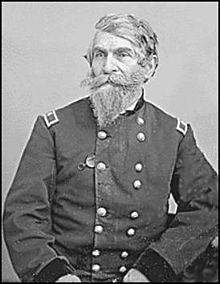

Brigadier General George Sears Greene

Brigadier General George Sears Greene

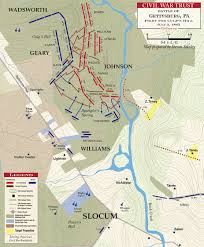

On the night of July 1st 1863 Dick Ewell’s Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac on Cemetery and Culp’s Hill prepared for another day of battle. Despite a significant amount of success Lee’s Army had failed to drive the lead elements of the Army of the Potomac off of Cemetery Hill. As the evening progressed more Federal troops in the form of Henry Slocum’s XII Corps began to take up positions on Cemetery Hill as well as Culp’s Hill which Oliver Howard and Winfield Scott Hancock recognized to be vital to holding the Federal position.

The three brigades of Geary’s division entered the line to the east of Wadsworth’s division of I Corps along the northern and eastern face of Culp’s Hill. Key to the position was the placement of the brigade of Brigadier General George S. Greene one of the oldest, if not the oldest Union officer on the field. Greene’s brigade took a position next to the remnants of the Iron Brigade which had fought so hard along Seminary Ridge earlier in the day.

Greene had been born in 1801 and had graduated from West Point as an artillery officer some six years before Robert E. Lee. He graduated second in his class at West Point in 1823 and after 13 years left the army in 1836 to enter civilian life as an engineer. Greene missed the Mexican War but when the call came for volunteers in 1861 he was appointed to command the 60th New York Volunteer Infantry. Promoted to Brigadier General in 1862 he commanded his brigade and served as an acting division commander at Antietam. He was a descendent of Nathaniel Greene and his son Lieutenant Dana Greene USN was the Executive officer of the USS Monitor at the Battle of Hampton Roads against the CSS Virginia.

As the Federal units on Culp’s Hill took their positions they began to do something that was not yet commonplace in either army. They began to construct field fortifications and breastworks. Working through the night with the ample materials at hand they dug in and linked their positions with each other as well as Brigadier General Thomas Kane’s brigade to Greene’s right. The line of fortifications took advantage of the natural terrain which on its own made the ground good for the defense, but when fortified made it nearly impregnable to assault.

During the day of July second little happened on Ewell’s front. Though he had persuaded General Lee to leave his troops in place Ewell remained mostly inactive on July second with the exception of some skirmishing and a battle between the Stonewall Brigade and Gregg’s division of Federal Cavalry on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge about two and a half miles east of the town.

It would not be until the evening of the 2nd that Ewell’s troops went into action against the now very well entrenched Federal Forces on Cemetery and Culp’s Hill. The assaults began on Cemetery Hill where Jubal Early’s division attacked forces along the north and east section of the hill to be supported by Robert Rodes’ division on the west.

However as with most of the Confederate offensive actions of the battle this too fell apart as Rodes division gave little support to Early’s attack as due to both Rodes’ and Ewell’s indecisiveness Rodes “did not give himself enough time to get his big division into formation for the attack. By the time he had completed the complicated maneuver of wheeling his brigades forty-five degrees to the left and advancing them half a mile to a good place from which to charge up Cemetery Hill the battle was over.” [1]

Though Early achieved some success his division was repulsed and the threat to the Union gun line on Cemetery Hill was ended. One author noted of Early’s attack: Courage and determination could not offset superior numbers and fresh troops. With no help coming and enemy units swarming around them, all those Rebels who were still under some command and control began to fall back.” [2]

Longstreet’s attack on the Federal left forced George Meade to pull troops from his quiet sector along Culp’s Hill in order to reinforce his forces in the Peach Orchard, the Wheat Field and along the southern extension of Cemetery Ridge. According to most accounts Meade directed Slocum to send “at least one division” to the threatened sector which weakened the forces deployed on Culp’s Hill considerably.

However within XII Corps there was much confusion and in addition to William’s division Geary had pulled two of his brigades out of line leaving only George Greene’s brigade to defend Culp’s Hill “guarding nearly half a mile of Twelfth Corps works.”[3] Neither Slocum nor Williams realized the danger and before the units which had left the hill could return Allegheny Johnson’s division of Ewell’s corps which had sat inactive and impatiently awaiting orders to attack all day jumped off.

149th New York Volunteer Infantry on Culp’s Hill

149th New York Volunteer Infantry on Culp’s Hill

The Confederate attack began around Seven PM and continued through the night. Johnson sent some 4,700 men to attack Greene’s 1,300 dug in veterans. “That kind of manpower edge would have likely been decisive elsewhere on the field that day, but against Pop Greene’s providential and well-constructed breastworks the odds leveled out.” [4]Greene’s men fought hard as Greene directed them and requested reinforcements from I Corps and XI Corps who in turn sent units including the Iron Brigade to help. However, the six regiments that arrived had been reduced to fractions of their former strength by the first day’s battle “increased Greene’s force only by about 755 men.” [5]Additionally, Hancock who heard the battle raging “sent two regiments to the relief of Slocum as well.”[6] Greene’s report of the battle noted:

“we were attacked on the whole of our front by a large force few minutes before 7 p.m. The enemy made four distinct charges between 7 and 9.30 p.m., which were effectually resisted. No more than 1,300 were in our lines at any one time. The loss of the enemy greatly exceeds ours.”[7]

As the night wore on Confederate attacks continued and in the darkness other Federal units arrived, including those from XII Corps which had gone earlier in the day. By mid-morning Johnson’s assault was done. His units had suffered severe casualties and his division had been drained of all attacking power by the time Lee needed it on the morning of July 3rd to support Pickett’s attack. “This division, formed by Stonewall Jackson was never the same again. Its glories were in the past.”[8] In the end the Army of the Potomac still held both Cemetery and Culp’s Hill, in large part due to the actions of the old soldier, George Greene who’s foresight to fortify the hill and superb handling of his troops and those who reinforced him kept Johnson’s division from rolling up the Federal right.

Ewell’s troops would play no further role in the battle. In the end his presence around Cemetery and Culp’s Hill diminished the resources that Lee needed to support his other assaults on the second and third day of battle. In effect it left Lee without one third of his forces. The result was the sacrifice of many troops with nothing to show for it. Ultimately Lee is to blame for not bringing Ewell’s forces back to Seminary Ridge where they and their artillery may have had a greater effect on the battle.

Monument to General George S Greene on Culp’s Hill

Monument to General George S Greene on Culp’s Hill

The real hero of Culp’s Hill was Greene. But Greene in many ways is a forgotten hero, he was not given much credit in Meade’s after action report though Slocum attempted to rectify this and Meade made some minor changes to his report. But it was in later years that Greene was began to receive recognition for his actions. James Longstreet gave Greene credit for saving the Union line on the night of July 2nd and said that “there was no better officer in either army” at the dedication of the 3rd Brigade monument on Culp’s Hill in 1888. Greene died in 1899 having been officially retired from the Army in 1893 as a First Lieutenant, his highest rank in the Regular Army. A monument to Greene stands on Culp’s Hill looking east in the direction of Johnson’s assault.

Until tomorrow,

Peace

Padre Steve+

[1] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster Ne5w York, 1968 pp.429-430

[2] Tredeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.409

[3] Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC 1993 p. 204

[4] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.326

[5] Ibid. Coddington p.431

[6] Jordan, David M. Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life Indian University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1988 p.94

[7] Luvaas, Jay and Nelson Harold W. editors. The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg South Mountain Press, Carlisle PA 1986 pp. 159-160

[8] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.262