This is the second “backgrounder” that I am posting to help my readers not acquainted with the War in the Pacific who desire to whet their whistle so to speak get an introduction to this war. While the series appears to be very well done it cannot provide the broad overview and references needed if a person really wants to know more. I believe that those who appreciate the story of the Marines portrayed in the series can help pass this on to others by learning more themselves about the subject. I hope that this will encourage you my readers never to forget the Marines depicted in “The Pacific.”

Decision

Guadalcanal came to American attention in early 1942 as a result of the Japanese South Pacific advance, which “threatened the Allied line of communications with Australia.”[1] Admiral King believed that “the Japanese must not be permitted to consolidate the formidable prizes” that they were then in the course of gathering.”[2] General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz both wanted to “exploit the Midway victory by a speedy change-over from the defensive to the counter offensive.”[3] MacArthur wanted to strike Rabaul directly using Navy carriers. The Navy, not wanting to give up control of its carriers proposed a strategy of working up through the Solomon Islands, under Navy control.[4] The debate was at times acrimonious. Eventually King and General Marshall worked out a compromise that divided the campaign between the Navy and MacArthur,[5] the Navy in charge of taking Guadalcanal and Tulagi.[6] OPERATION WATCHTOWER was approved in a Joint Chief’s of Staff directive on July 2nd 1942.[7]

Partners Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner and Major General Alexander Vandegrift

Partners Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner and Major General Alexander Vandegrift

The Japanese had not initially placed a high priority on the Solomons, “as they did not expect a counteroffensive in the Pacific for months.”[8] However, after Coral Sea and Midway, they authorized operation “SN” to “strengthen the outer perimeter of Japan’s advance by constructing airfields at key strategic points….”[9] The Japanese sent a contingent of troops, which arrived on June 8th[10] to build an airfield on Guadalcanal, in addition to the seaplane base on Tulagi, as part of a strategy to take the offensive in the South Pacific with an attack on Port Moresby in mid-August.[11]

Japanese commanders were impatient for the airstrip to be completed, yet work began at a leisurely pace, with the Japanese unaware that every move was being “watched and reported to Allied headquarters in Australia,” by coast-watchers.[12] As the Japanese on Guadalcanal dithered the Americans rushed their preparations for the invasion[13] nicknamed “SHOESTRING” by American officers.

The Landings and Initial Actions through the Ilu (Tenaru) River

Marines coming ashore at Guadalcanal

Marines coming ashore at Guadalcanal

Preparations, though rushed enabled the 1st Marine Division under General Vandegrift to embark on transports for Guadalcanal, despite not being combat loaded and having been assured that they “need not expect a combat mission before 1943.”[14] The invasion force under the overall command of Admiral Fletcher and Admiral Richmond “Kelly” Turner set sail on July 25th and cloaked by heavy rain and clouds[15] remained undetected by the Japanese until they arrived in the waters off Guadalcanal, achieving complete surprise.[16] The invasion force landed on both Tulagi and Guadalcanal. On Tulagi, 1st Raider Battalion under Colonel Edson and 2nd Battalion 5th Marines quickly drove off the 350 Japanese defenders of the 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Force,[17] and in three days eliminated the Japanese garrison which resisted to the death, with only 23 prisoners.[18] On nearby Gavutu-Tanambogo 1st Parachute Battalion subdued the Japanese personnel operating the seaplane base, though not without difficulty, the naval bombardment was ineffective[19] and the Parachutists suffered heavy casualties[20] and forcing the commitment of the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 2nd Marines.[21] Across the sound the main force of 1st Marine Division went ashore near Lunga Point with 5 infantry battalions. The Marines rapidly ran into difficulty, not due to the Japanese garrison, which melted into the jungle,[22] but to a lack of maps, the thick jungle and kuni grass, their own “deplorable physical condition” from being shut up in the holds of the transports for two weeks and overburdened with full packs and extra ammunition.[23]

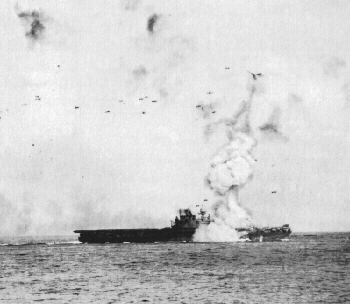

Japanese “Betty” Bombers attacking US Transports

Japanese “Betty” Bombers attacking US Transports

While the Marines advanced inland, supplies built up on the landing beaches due to the limited number of cargo handlers. Additionally, the Japanese launched a number of heavy air raids which caused minimal damage to the destroyer Mugford on the 7th but were more successful on the 8th damaging a transport badly enough that it had to be abandoned.

Marine M3 Stuart Light Tank and Crew at Guadalcanal

Marine M3 Stuart Light Tank and Crew at Guadalcanal

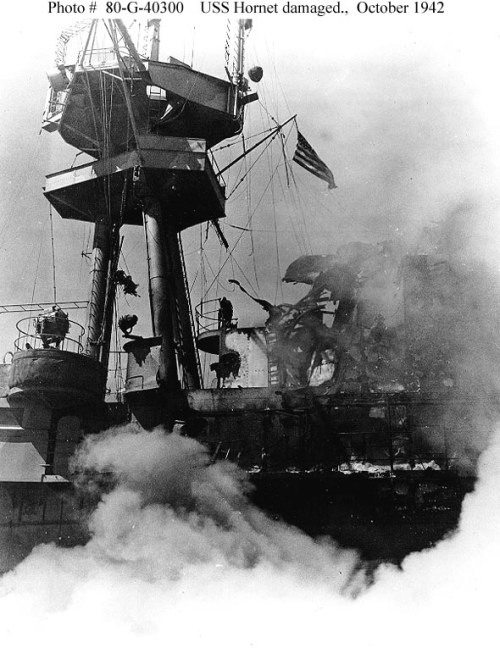

The Marines on Guadalcanal, comprised of the 1st and 5th Marine Regiments consolidated a bridgehead around the captured airfield on the 8th, but the next day found that their situation had changed dramatically. The Japanese Navy had attacked and mauled the covering force, sinking four cruisers and damaging one at the Battle of Savo Island.[24] The destruction of the covering force and Admiral Fletcher’s withdraw of the carriers forced the transports to depart on the 9th, still bearing much equipment, supplies and nearly 1800 men of the 2nd Marines.[25] Vandegrift was left with only 5 infantry and 3 artillery battalions, and the 3rd Defense battalion on the island as well as some tanks, engineers and Navy “Seabees.”[26] When the Navy left Vandegrift went over to the defensive and organized a line from the Ilu river on the east to Lunga point and the airfield to a point about 1000 yards past Kukum.[27] Defenses were prepared to defend against potential Japanese amphibious attacks. 1st Marines held the eastern perimeter and 5th Marines (-) the west. One battalion with tanks and half-tracks was reserve. The line was thin and not continuous, thus Vandegrift could only watch and wait for the Japanese strike and move “part of his mobile reserve to meet it when it came.”[28] On the 12th a prisoner reported that Japanese near Matanikau were willing to surrender and LtCol Goettge the G-2 led a 25 man patrol to investigate. The patrol was ambushed and decimated with only three survivors.[29] The Japanese landed the advance party of the 5th Special Naval Landing Force in broad daylight on the 16th, and Vandegrift decided to bring 2/5, and the Raider and Parachute battalions from Tulagi as soon as he had ships to do it.[30] On the 20th the airfield was opened and a squadron each of Marine Fighters and Dive Bombers landed on Guadalcanal.[31]

Makeshift Obstacles: With no barbed wire the Marines used the ingenuity

Makeshift Obstacles: With no barbed wire the Marines used the ingenuity

General Hyakutake of the 17th Army was allotted 6,000 men of the Special Naval Landing Force, and the Kawaguchi and Ichiki detachments to re-take Guadalcanal. 17th Army also had the Sendai 2nd and the 38th Divisions, tank and artillery units, but they were scattered from Manchuria, to Borneo and Guam.[32] Hyakutake was ordered to use only the Ichiki detachment, a move which some at Imperial GHQ vigorously opposed.[33] Kawaguchi, recognized Guadalcanal’s importance and told a reporter that “the island would be a focal point in the struggle for the Pacific.”[34] On the 18th Colonel Ichiki landed with half of his unit, 915 men, 25 miles east of the Marines. Overconfident, he disobeyed orders to wait for the rest of his troops, left 125 men behind to guard his bridgehead and set off to attack.[35]

Colonel Ichiki whose elite 5th Special Naval Landing Force was annihilated at the Tenaru River

Colonel Ichiki whose elite 5th Special Naval Landing Force was annihilated at the Tenaru River

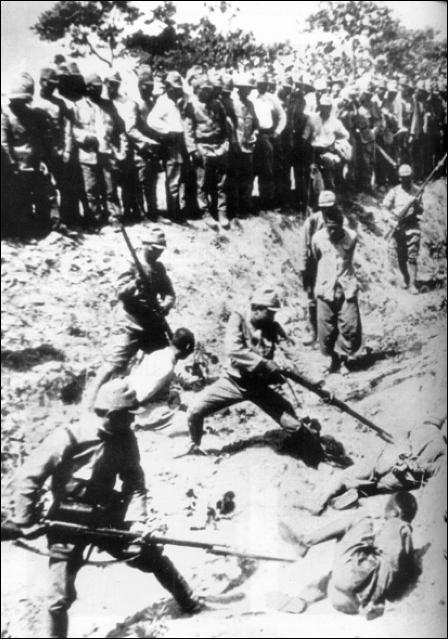

Ichiki’s force attacked shortly after 0100 on the 21st. He thought that he had achieved surprise[36], but, opposing him was 2nd Battalion 1st Marines under LtCol. Al Pollock. Warned by patrols that encountered the oncoming Japanese, and by Sergeant Major Vouza,[37] the Marines were on alert, well dug in, though lacking barbed wire, of which a single strand was emplaced across their front. The Japanese ran into the barbed wire and were mowed down as they attempted to cross the sandspit against G/2/1 and a weapons platoon. About 0300 artillery joined the action, catching the Japanese bunched together near the sandspit inflicting heavy casualties.[38] Around 0500 Ichiki made another attempt, sending a company through the surf, which was engulfed in machine gun and artillery fire.[39] At daylight the Marines counter attacked. Colonel Cates ordered Lt.Col. Cresswell’s 1st Battalion 1st Marines, to envelop the Japanese along the beach. Pollock’s Marines ranged mortars and small arms fire on Japanese survivors to their front, picking them off “like a record day at Quantico”

Dead Japanese of the Ichiki Detachment at the Tenaru

Dead Japanese of the Ichiki Detachment at the Tenaru

[40] Marine aircraft made their first appearance, strafing the Japanese survivors. A light tank platoon crossed the Ilu and began to mop up the Japanese with 1/1 at 1530. At 1630 Ichiki burned his regimental colors and committed suicide. The Battle of the Ilu was over, the Japanese suffering at least 777 dead,[41] 15, 13 of whom were wounded were captured, only a Lt. Sakakibara and one soldier escaped to join those at the landing site.[42] The Marines suffered 35 dead and 74 wounded.[43] Ichiki made critical mistakes; he failed to reconnoiter, made a frontal attack against a dug in enemy and repeated it, with disastrous results.[44] Hyakutake informed Tokyo: “The attack of the Ichiki detachment was not entirely successful.”[45] The Americans were shocked at the Japanese fight to the death, and Griffith would note: “from this morning until the last days on Okinawa, the fought a ‘no quarter’ war. They asked none for themselves. They gave none to the Japanese.”[46]

Bloody Ridge

Artists depiction of Sgt Mitchell Paige assaulting attacking Japanese units at Bloody Ridge

Artists depiction of Sgt Mitchell Paige assaulting attacking Japanese units at Bloody Ridge

A round of minor engagements was fought in late August and early September as each side sent reinforcements. Kawaguchi’s brigade landed between August 29th and September 4th, but many troops were lost due to air attacks on the destroyers, transports and barges. Kawaguchi received the remainder of Ichiki’s force, bringing his force to 6200 men. He refused Hyakutake’s offer of an additional infantry battalion, believing intelligence that only 2000 Marines remained on Guadalcanal.[47] In fact Vandegrift had already moved the Raiders, Parachutists from Tulagi to Guadalcanal. Most of Kawaguchi’s force was east of the Marines; elements of 4th Regiment under Colonel Oka were on the Matanikau.[48] Vandegrift used the Raiders to attack Kawaguchi’s rear areas, capturing Tasimboko and killing 27 Japanese, destroying many of his troop’s supplies and foodstuffs.[49] Kawaguchi was infuriated by the attack and 17th Army prepared to send troops from the Sendai 2nd Division to the island.

Vandegrift and Key Marine Leaders

Vandegrift and Key Marine Leaders

The Raiders and Parachutists took positions on a ridge south of Henderson field on their return from the raid against Kawaguchi’s rear. Vandegrift placed his “Amtrackers” to the west of the ridge with 1st Pioneer Battalion.[50] Colonel deValle’s artillery was emplaced to give close support and observers attached to Edson’s battalion. The artillery was registered on pre-plotted points.[51] Edson’s force had little time to prepared defenses and due to the ridge and jungle prevented him from having “anything like a continuous line.”[52] First Marines held the line from Edson’s left to the sea along the Ilu. Unlike Ichiki, Kawaguchi avoided an attack on the strong 1st Marines position, and headed across the jungle to attack the airfield from the south with the 124th Infantry Regiment. Due to the difficult approach his battalions had a hard time reaching their start positions, two of the three reached the assembly areas two and three hours after the start time. When they did attack they lost their way, became scattered and intermingled; and Kawaguchi his battalion commanders lost all control.[53] The attack on the 12th was frustrating to Kawaguchi who later wrote “In all my life I have never felt so helpless.”[54] The attack was so ineffective that Edson thought the Japanese were “testing” him.[55]

Marine Artillery on Guadalcanal

Marine Artillery on Guadalcanal

Kawaguchi regrouped as did Edson, who pulled back his line 200 yards to a stronger point on the ridge, reorganizing the line and command and control.[56] This improved fields of fire for his automatic weapons.[57] 2nd Battalion 5th Marines, the only reserve was moved south of the airfield so it could relieve Edson on the 14th.[58] As darkness fell, the Japanese attacked. I/124 attacked the ridge and the area to the west. Marines withdrew up the ridge under heavy pressure supported by artillery, which dropped fires almost on top of the Raider positions.[59] During the withdraw the Parachutists became confused and continued to withdraw, and only stopped when Edson’s operations officer, Major Bailey stepped in and halted it.

Artists depiction of the Battle of Bloody Ridge

Artists depiction of the Battle of Bloody Ridge

Artillery pounded I/124 and halted its attack even as companies of the reserve, 2nd battalion 4th Regiment attacked forcing the Raiders back to a knoll, the last defensive position before Henderson Field.[60] Edson exhorted the Marines who threw the Japanese back, and parachutists under Captain Torgerson counterattacked. Two more attacks were repulsed with assistance from 2/5 which had moved up in support.[61] The third Japanese battalion did not get into action[62] and Colonel Oka in the west made a weak attack that was handily defeated. The Japanese lost over 1200 men in their attack on the ridge.[63] The demoralized Japanese retreated west to join Oka’s men, taking a week and costing even more casualties.[64] Short on food, Oka pushed the survivors west and so he could defend the river line.[65]On the 18th Vandegrift was reinforced with 4700 men of the 7th Marines along with trucks, heavy equipment and supplies.[66] Edson was promoted to command 5th Marines.[67]

Matanikau Battles and the Fight for Henderson Field

Marine F4F Wildcat on Henderson Field

Marine F4F Wildcat on Henderson Field

The Japanese now decided to send the Sendai and 38th divisions and heavy artillery to the island. Hyakutake went to the island to direct the campaign. The decision resulted in the suspension of 17th Army’s offensive against Port Moresby.[68] Admiral Yamamoto committed the fleet to cover the operations[69] setting up a major air, land and sea confrontation with the Americans. However before these forces could reach the island Vandegrift launched a series of attacks against Oka’s force on the Matanikau using the Raiders, and elements of 5th and 7th Marines.[70] The first attacks took place 24-27 September. The Matanikau position was important to future Japanese operations as their artillerymen stressed that they could not effectively shell the airfield unless guns were emplaced across the river.[71] The Raiders attacked at the log bridge[72] supported by C/1/7 and were repulsed by Oka’s 12th Company with heavy casualties.[73] Puller’s attack by 2/5 and parts of 1/7 at the mouth of the river was rebuffed by 9th Company. An amphibious assault by three companies of 1/7 was ordered by Edson who mistakenly believed that his Marines had crossed the river.[74] The force isolated by Oka’s II/124 and 12th Company, its commander killed and the Marines had to be rescued by Navy units.[75]

Navy Corpsmen preparing to evacuate a wounded Marines (above) and the 1st Marine Divsion Field Hospital

Navy Corpsmen preparing to evacuate a wounded Marines (above) and the 1st Marine Divsion Field Hospital

A second attack by the Marines on the Japanese, now reinforced by 4th Infantry Regiment on 6-9 October dealt them a crushing blow. An attack by 2/5 and 3/5 along the coast met heavy Japanese resistance and General Nasu decided to push across the river. While this was taking place, 7th Marines and the Whaling Group[76] outflanked the Japanese on the river and pushed to the coast. The Marines mauled the 4th Infantry, a Japanese report noting at least 690 casualties.[77] The action had decisive impacts on the next phase of Japanese operations.

General Hyakutake Commander of the Japanese 17th Army defending Guadalcanal

7th Marines and the 164th Regiment of the Americal Division arrived allowing Vandegrift to mount a full perimeter defense while Admiral Halsey replaced Ghormley as COMSOPAC.[78] Arriving on 10 October with the Sendai Division and 17th Army Artillery, Hyakutake, was notified that “American artillery had ‘massacred” the Fourth Infantry Regiment”[79] and found Ichiki and Kawaguchi’s units in an emaciated condition, the total effectives of the 6 battalions numbering less than a full strength battalion.[80] He radioed Rabaul “SITUATION ON GUADALCANAL IS MUCH MORE SERIOUS THAN ESTIMATED, and asked for more reinforcements and supplies at once.”[81] The Navy turned back a Japanese bombardment group on the 12th, but battleships and cruisers blasted Henderson Field on the 13th, 14th and 15th, destroying many aircraft.[82]

The 14″ guns of the Japanese Battleship Kongo and her sister Haruna pounded Henderson Field

The 14″ guns of the Japanese Battleship Kongo and her sister Haruna pounded Henderson Field

Hyakutake received reinforcements including tanks and an infantry-artillery group and prepared to attack. General Sumiyoshi[83] was to make a diversionary attack along the coast with Army artillery and 5 infantry battalions. The Sendai Division under General Maruyama[84] with 9 infantry battalions moved inland along a route “the Maruyama road,”[85] to make the main effort to attack the airfield from the south. Sumiyoshi divided his artillery to support the bombardment of Henderson Field and support his infantry attacks, but was short ammunition.[86] The Marines had fortified the eastern side of the Matanikau and Sumiyoshi probed the Marines with infantry and tanks and artillery fire on the 20th and 21st, giving the Marines their first taste of concentrated artillery.[87] Sumiyoshi’s demonstration on the coast was effective, and Maruyama’s division remained undetected throughout its advance avoiding Marine and native patrols.[88]

Japanese dead after the failed attack on Henderson Field

Japanese dead after the failed attack on Henderson Field

The attack began on the 23rd with Sumiyoshi attacking on the Matanikau; but he did not get the word that the attack for that night had been postponed until the 24th since Kawaguchi’s units had not gotten to assembly areas on the right of Sendai division.[89] His tanks advanced at 1800 and all but one were destroyed by deValle’s artillery as soon as they moved across the sandspit. The supporting infantry withdrew, and most never went forward as they were hit hard in assembly areas by Marine artillery losing over 600 men.[90] The action succeeded in the Marines shifting 2/7 and 3/7 north leaving Puller’s 1/7 alone on “Bloody Ridge.”[91] Fortunately for the Marines these Japanese forces were detected by Scout-Sniper’s[92] and Puller dug in his battalion deeper and set out a platoon in an outpost 1500 meters south of his position.[93]

On the 24th Maruyama’s Sendai troops attacked the ridge. He divided his force into two wings each of three infantry battalions commanded by General Nasu on the left and Colonel Shoji[94] on the right, three battalions served as a reserve. He advanced at 1900 but a storm turned the jungle into a vast mud bog exhausting the Japanese. Shoji’s wing advanced tangential to the Marine line and only one battalion made contact with Puller’s battalion.[95] Nasu’s troops hit Puller’s who realized that he was facing a major attack; he fed platoons from 3rd Battalion 164th Infantry, a National Guard unit into his lines and requested reinforcements.[96] The Marines and Guardsmen beat back all but one attack, that of LtCol. Furimiya of III/29 who got into the Marine perimeter and held out 48 hours, colors flying, leading Hyakutake to believe that they had captured the airfield.[97] The Japanese were driven off 9th Company of the 29th Regiment was wiped out primarily by the efforts of Sgt. John Basilone’s machine gun section.[98]

Wrecked Aircraft on Henderson Field

Wrecked Aircraft on Henderson Field

The next day was known as “Dugout Sunday”[99] and that night the Japanese renewed the attack. This was better coordinated, but the Marines, reinforced by 3/164 and 3/2, and backed by artillery, devastated the Sendai division. Nasu and the commander of 16th Infantry were killed with at least 2000 of their soldiers.[100] Colonel Oka attacked 2/7 and was driven off with heavy casualties. Marine Sgt. Mitchell Paige won the Medal of Honor for single handedly manning his platoon’s machine guns after his troops became casualties, going gun to gun.[101] The attacks were crushed leaving more than 3000 dead or dying Japanese on the battlefield.[102]

On the Offensive

As the Japanese struggled out of jungle to the coast the Marines began preparations to attack as each side brought in reinforcements, the Americans receiving the 8th Marine Regiment and 2nd Raider Battalion of 2nd Marine Division, as well as the 2nd Marines who had been on Tulagi and more of the Americal Division.[103] On November 1st and 5th Marines attacked across the Matanikau and by the 4th had eliminated a Japanese pocket on Point Cruz.[104] To the east 1/7 and 2/7 along with 2/164 and 3/164 attacked Col. Shoji’s force and fresh troops sent to relieve him near Koli Point. The battle lasted until the 9th when Shoji broke through the American cordon with 3000 men pursued by 2nd Raider Battalion. Shoji eventually made it back to 17th Army with 700-800 soldiers, most unfit for combat after battling the Raiders and the jungle.[105] The Japanese attempted to reinforce the island during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal from 13-15 November. Out of 11,000 troops of 38th Division on 11 transports only 2000 got ashore after 7 of the 11 were sunk enroute by Henderson Field aircraft and the surviving ships beached.[106]

The Americans received the rest of 2nd Marine and Americal Divisions and parts of 25th Division and Vandegrift decided to attack, his command now being a de-facto Corps.[107] Though they still numbered 30,000 the Japanese were incapable of offensive operations but still full of fight.[108]On 18 November the 8th Marines and the Army and elements of the 164th and 182nd regiments attacked on the Matanikau. They met heavy resistance from Col. Sakai’s 16th Infantry and in a 6 day battle and lost 134 dead with minimal gains.[109] The new arrivals allowed 1st Marine Division to be withdrawn[110] as it was no longer combat effective.[111] On 9 December Vandegrift[112] turned over command to General Alexander Patch of the Americal Division.

Advancing across a improvised pontoon bridge

Advancing across a improvised pontoon bridge

Patch used early December to conduct aggressive patrolling[113] and decided to clear the Japanese from Mt Austen, which they had nicknamed “Gifu” and in a 22 day battle the 132nd Infantry eliminated the 38th Infantry Group.[114] With the 25th, Americal and 2nd Marine Division Patch now headed XIV Army Corps.[115] Although the Americans were unaware the Japanese had decided to withdraw from Guadalcanal on 31 December, after a heated debate.[116]

Major General Vandegrift, Colonel Edson, 2nd Lt Mitchell Paige and Sgt John Basilone all awardees of the Medal of Honor

Major General Vandegrift, Colonel Edson, 2nd Lt Mitchell Paige and Sgt John Basilone all awardees of the Medal of Honor

The final offensive began on 10 January. Patch hoped to clear out the Japanese by April.[117] The 2nd Marine Division attacked along the coast while General Lawton Collins led his 25th Division in a flanking movement heavily supported by artillery and air. 6th Marine Regiment relieved 2nd Marines flanking the Japanese enveloped the majority of the 4th and 16th Regiments.[118] The Japanese began withdrawing on the 17th moving west shielded by the Yano battalion.[119] Collins troops finally reduced and eliminated the Japanese on the Gifu by the 23rd.[120] “The annihilation of Japanese detachments from regimental size down” characterized operations over the final phase of the command.[121] A characteristic of American operations now included the use of heavy massed artillery including time on target or “TOT” missions.[122] On the 22nd the Japanese began to extricate their troops via the Tokyo Express at Cape Esperance.[123] On 1 February Patch landed 2/132 at Verahue on the southwest tip of the island and the 25th and Americal Divisions continued their push to the west against the rearguards of 17th Army. On the 8th of February the last survivors were withdrawn[124] in a move described by the Chief of Staff 17th Army as a “minor miracle.”[125] The Japanese were shocked that the Americans “press them hard” and turn the withdraw “into a bloody rout.”[126] Still expecting a fight Patch’s troops found nothing on Cape Esperance but abandoned boats and supplies.[127]

The Guadalcanal campaign had ended with the loss of nearly 30,000 Japanese. Japan lost the psychological advantage it had possessed from the beginning of the war.[128] It was an action that was an offensive won with defensive actions. The Americans seized a strategic point that the Japanese could not afford to lose and then fought a defensive battle of attrition to grind the Japanese down. The American Marines and Soldiers showed themselves to be the equals of the Japanese in one of the most demanding campaigns of the war. Kawaguchi would comment to a reporter in Manila; “We lost the battle. And Japan lost the war.”[129]

Appendix: Leaders On Guadalcanal

Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift: (1887-1973) Commander of 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal. He served in the Corps 40 years and retired in 1949 as Commandant of the Marine Corps. After Guadalcanal he commanded 1st Marine Amphibious Corps at Empress Augusta Bay. He was a key player in the congressional debates regarding the Marine Corps in 1946 when President Truman supported by the Army pushed to eliminate the Marine Corps as a ground combat force. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his service at Guadalcanal. USS Vandegrift FFG-48 was named after him. That ship made the first visit of a US warship to Vietnam since the Vietnam War in 2003.

Major General Alexander Patch: (1889-1945) Commander of XIV Army Corps at Guadalcanal. He assumed command of forces on island from Vandegrift on 9 December 1942. General Marshall ordered him to Europe in 1943 to take command of 7th Army from General Patton. He commanded 7th Army in the south France and the Rhone campaign of 1944, leading that army across the Rhine in 1945. He was to take command of 4th Army in the United States but died of Pneumonia. He was considered a very good commander in both the Pacific and Europe. Patch Barracks in Stuttgart Germany is named after him.

Major General Lawton Collins: (1896-1987) “Lightning Joe” Collins commanded 25th Infantry Division (Tropical Lightening) at Guadalcanal. He commanded VII Corps and distinguished himself in France and was instrumental in Operation COBRA and the breakout from Normandy. He was considered by many to be one of the outstanding Corps commanders in the Second World War. During Korea he was Army Chief of Staff and later served with NATO and as a special representative to Vietnam.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller: (1898-1971) “Chesty Puller commanded 1st Battalion 7th Marines at Guadalcanal and was instrumental in the fight for Henderson Field against the Sendai Division. His early career was marked by much time in Haiti and Nicaragua where he was awarded his first and second Navy Crosses. He served with the “China Marines” (the 4th Marines) He was wounded on Guadalcanal and later served as Executive Officer 1st Marine Regiment and commanded that Regiment at Peleliu. In Korea he again commanded 1st Marines at the epic Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. He was promoted to Brigadier General and served as Assistant Division Commander for that Division. He was promoted to Major General and Lieutenant General prior to his retirement in 1955. He is considered one of the most iconic and beloved Marines who have ever lived earning 5 Navy Crosses and numerous other awards for valor in combat include the Bronze and Silver Stars and Distinguished Service Medal and the Purple Heart. The USS Puller (FFG-23) a Perry Class Frigate was named after him. His uniforms and many of his medals and citations were displayed at the former Marine Corps Barracks, Naval Weapons Station Yorktown until 2006 when they were transferred to the custody of the Marine Corps Museum following the death of his wife Virginia who insisted that they be displayed in Yorktown.

General Harukichi Hyakutake: (1888-1947) Commanded 17th Army on New Guinea and Guadalcanal. He was an infantry officer who studied crypto analysis and served with the Kwantung Army in Manchuria before the war and following Guadalcanal he remained in command of Japanese Troops in the Solomons. He returned to Japan at the end of the war and died in 1947.

Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi: (1892-1961) Commanded 35th Infantry Brigade on Guadalcanal and was senior officer until the arrival of General Hyakutake and the Sendai Division. Led the unsuccessful battle at “Bloody Ridge” and was relieved of his command just prior to the October attack on Henderson Field. Was one of the few Japanese officers who expressed an early understanding of the importance of Guadalcanal to the overall war effort. Following his evacuation from Guadalcanal and return to Japan he was transferred to the reserve. Convicted of war crimes in 1946 for actions committed in the Philippines in 1941-42 he was released in 1953 and died in 1961.

Notes

[1] Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan, The Free Press, New York, NY p.185

[2] Morison, Samuel Elliott, The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War, Little, Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto, 1963. p.164

[3] Liddle-Hart, B.H. History of the Second World War G.P. Putnam’s Son’s. New York, NY 1970. 356

[4] Ibid. Spector. p.185

[5] Ibid. Spector comments that “MacArthur declared that the navy’s obstinacy was part of a long time plot to bring about ‘the complete absorption of the national defense function to the Navy, the Army being regulated to merely base, training, garrisoning, and supply purposes.’” (p.185)

[6] Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945, Random House Publishers, New York, 1970. p.346

[7] Ibid. Morison. p.165

[8] Ibid. p.350

[9] Frank, Richard B. Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle, Penguin Books, New York, NY 1990. p.30

[10] Ibid. p.31

[11] Ibid. Morison. p.166

[12] Griffith, Samuel B II. The Battle for Guadalcanal originally published by Lippincott, New York, 1963, University of Illinois Press, Champaign IL, 2000. p.19

[13] Costello, John. The Pacific War 1941-1945, Quill Publishers, New York, NY. 1981. p.320.

[14] Ibid. Spector. p.186

[15] Ibid. Frank. p.60

[16] Ibid. Spector. p.191

[17] Ibid. Frank. p.72

[18] Ibid. Costello. p.323

[19] Ibid. Griffith. p.49

[20] Ibid. Frank. p.72. 1st Raider Battalion took 22% casualties and 1st Parachute Battalion 50-60%.

[21] Ibid. Frank. p.74. Frank notes that of the 536 Japanese defenders that only about 50, a platoon from the 3rd Kure Naval Landing force were trained for ground combat.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid. Griffith. p.45

[24] Savo Island was the worst defeat suffered by the US Navy. In a short engagement the heavy cruisers Astoria, Quincy and Vincennes and the RAN Canberra were sunk and the Chicago badly damaged, leaving the covering force but one heavy cruiser and some AA Cruisers and Destroyers to cover the transports. Over 1000 sailors lost their lives.

[25] Ibid. Frank. p.125

[26] Costello notes the presence of the Seabees, but neither Franks nor Griffith mentions them by name. The discrepancy appears to be the date of their arrival on the island. Morrison notes that 387 men of the 6th Seabee Battalion landed on September 1st with 2 bulldozers and other equipment and that they then took over the improvement of Henderson Field. Morison, Samuel Elliott. The Struggle for Guadalcanal: August 1942-February 1943, Volume V of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Copyright 1949, Samuel Elliott Morison, Castel, Books New York, NY 2001, published in arrangement with Little Brown and Company. p.76

[27] Ibid. Griffith. p.68

[28] McMillan, George. The Old Breed: A History of the First Marine Division in WWII, The Infantry Journal Incorporated, Washington DC. 1949. p.50

[29] Ibid. Frank. p130, Griffith. p.70. McMillan pp.52-56. This incident is still shrouded in mystery as no Japanese records survive to record the outcome of the incident. According to McMillan, when Goettge went out he believed he was also on a humanitarian mission and took the assistant division surgeon and a language officer. The Goettge Field House at Camp LeJeune NC is named in his honor.

[30] Ibid. Griffith. p.74

[31] Ibid. McMillan. pp.56-57

[32] Ibid.. p.59

[33] Ibid. Griffith. pp.79-80 some believed the commitment of small numbers inadequate to the task would repeat the defeats suffered at the hands of the Russians and in China. Ichiki himself was given poor intelligence stating that there were only about 2000 Americans on the Island and that they suffered from low morale and were trying to flee Guadalcanal to Tulagi. (p.81)

[34] Ibid. Toland. p.364

[35] Ibid. p.365

[36] Ibid. p.366

[37] Ibid. McMillan. p.61. Vouza, a native constable had actually been captured and interrogated by the Japanese, who bayoneted him and left him for dead.

[38] Ibid. pp.61-62

[39] Ibid. Griffith. p.84

[40] Ibid. p.86

[41] Ibid. Frank. p.156. Richard Tregaskis in Guadalcanal Diary reports that he heard there were 871 Japanese dead in the battle area. Tregaskis, Richard, Guadalcanal Diary, Originally published by Random House, 1943. Modern Library Paperback edition, Random House Publishers, NY 2000, with an introduction by Mark Bowden. p.130

[42] Ibid. Toland. p.367 Griffith reports that a Captain Tamioka survived. (p.87)

[43] Various accounts give slightly different figures for the Marine casualties. This number is taken from McMillan.

[44] Ibid. Griffith. pp.87-88. Griffith comments: “there was something more fundamental involved here than action taken on the basis of poor information, a reckless and stupid colonel, dedicated soldiers, and a disparity in weapons. This was ‘face.’ Once committed to the sword, Ichiki must conquer or die. This was the code of the Samurai, ‘The Way of the Warrior’: Bushido. (p.88)

[45] Ibid. McMillan. p.64

[46] Ibid. Griffith. p.88

[47] Ibid. Frank. p.218. Toland reports that he received intelligence that 5000 Marines were on the island but he believed that he could be victorious. (p.378)

[48] Ibid. Toland. p.376. Oka’s force was particularly hard hit by the air attacks during transit, losing 650 out of 1000 men, and his survivors had little food and ammunition and were not in good condition to attack.

[49] Ibid. Frank. pp.221-222. They also brought back documents, Kawaguchi’s dress uniforms and beer.

[50] Vandegrift rusted in the understanding that every Marine is a rifleman.

[51] Ibid. Griffith. p.115

[52] Ibid. Frank. p.229

[53] Ibid. p.231

[54] Ibid. p.232

[55] Ibid. Griffith. p.117

[56] Ibid. Frank. p.235 He still lacked the manpower to form a continuous line.

[57] Ibid. Griffith. p.117

[58] Ibid. Frank. p.235

[59] Ibid. Griffith. p.119

[60] Ibid. Frank. p.239

[61] Ibid. p.240

[62] This was III/124 under Colonel Wanatabe, suffering from old war wounds he failed to get his unit into the fight and Kawaguchi told him to commit Hari-Kari. (Griffith .121)

[63] Ibid. Griffith. p.121. The Marines lost 263 men of which 49 were killed and 10 missing. The Parachute battalion which began the campaign with 397 men had only 86 ambulatory after “Bloody Ridge” and were withdrawn. (Frank. p.241)

[64] Ibid. Costello. p.346 Frank also notes that another of Kawaguchi’s battalions, the Kuma battalion and his artillery fared even worse while trying to move to the west, becoming lost in the jungle for three weeks, losing all their weapons and becoming severely malnourished. (Frank. p.246)

[65] Ibid. Griffith. p.125

[66] Ibid. Toland. p.385 The Japanese began to call the island Starvation Island.

[67] Edson and Bailey both were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for their actions on the ridge. (McMillan p.81)

[68] Ibid. Griffith. pp.126-127

[69] Ibid. Spector. p.199 and Costello. p.348

[70] Ibid. Frank. p.269.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Ibid. Griffith. p.135. Griffith refers to this as the “Jap bridge.” I use Frank’s the name given by Frank.

[73] Ibid. Frank. p.272

[74] Ibid. Toland.p.390

[75] Ibid. Frank p.273-274. Frank analyzes: “In a retrospective assessment, the Marines found that the operation had an improvised purposeless flavor. It had been initiated without meaningful intelligence on the enemy situation or the terrain, and the attack was characterized by the commitment of battalions along unreconnoitered axes, beyond mutual support range, and without coordination of movements or of air and artillery support.” (p.274)Griffith comments: “Here Edson, as always supremely confident, had dispersed his force haphazardly to assault an enemy well armed, well concealed, and at each pointing superior strength. Second Matanikau hammered home to Vandegrift that a commander who allows himself or a subordinate, to drift aimlessly into any action will pay the price. (Griffith p.137)

[76] Ibid. Griffith. p.283. The Whaling Group consisted of 3rd Bn 6th Marines and the Scout Sniper detachment.

[77] Ibid. 289. The Division history of 1st Marine Division reported over 900 Japanese killed. (McMillan p.96)

[78] Ibid. McMillan. p.99

[79] Ibid. Griffith. p.148

[80] Ibid. p.338

[81] Ibid. Toland. p.392

[82] Ibid. Griffith. p.157. By the 15th the Marines only had 27 aircraft left, but by the evening a Navy fighter squadron had reinforced them.

[83] Artillery commander 17th Army.

[84] Ibid. Toland. p.393. Maruyama noted before the division departed from Japan that Guadalcanal was the “Decisive battle between Japan and the United States, a battle in which the fate of the Japanese Empire will be decided.”

[85] Ibid.p.340 Toland notes how this “road” had been hacked out of the jungle in the proceeding month. (Toland. p.393)

[86] Ibid. p.342. The 15 150mm guns targeted the airfield and the remaining 17, 75mm and 100mm guns and howitzers targeted the infantry.

[87] Ibid. Griffith. p.165-166

[88] Ibid. Frank. p.348

[89] Ibid. Griffith. pp.166-167. Sumiyoshi was not at fault as he had fallen into a coma brought on by Malaria. Kawaguchi was relieved by Hyatutake for this failure.

[90] Ibid. p.167

[91] Ibid. McMillan. p.105

[92] Ibid. Toland. p.401. Frank notes that even this discovery did not alert the Marine command to the Japanese presence south of the ridge and he credit’s Puller’s lack of complacency.

[93] Ibid. Frank. p.352

[94] Ibid. Frank. Shoji had relieved Kawaguchi.

[95] Ibid. Frank. pp.352-353

[96] Ibid.. p.355-356

[97] Ibid. p.356. Furimiya would eventually commit suicide when he had lost the rest of his troops. His diary, found by the Americans made a note that “we must not overlook firepower.” (p.366) Griffith notes the officer as Ishimiya and notes that only 9 men were with him. (p.169)

[98] Ibid. p.356. Basilone won the Congressional Medal of Honor.

[99] The day was marked by a fierce air-sea battle between American aircraft and a Japanese naval task force sent to shell Henderson Field and supporting fighters. A number of Japanese ships were damaged and the light cruiser Yura sunk. See Morison. History of Naval Operations in WWII vol V. pp.197-198

[100] Ibid. Frank. pp.364-365

[101] Ibid. pp.363-364. I met Paige in 2000 at Camp LeJeune. This icon of the Corps remained an outspoken Marine until the day that he died.

[102] Ibid. Toland. p.404

[103] Ibid. Liddle-Hart. p.361

[104] Ibid. Griffith. p.184

[105] Ibid. Frank. pp.421-424.

[106] Ibid. Morison. History of Naval Operations. p.182. Frank backs this number and Liddle-Hart gives 4000.

[107] Ibid. McMillan. p.135

[108] Ibid. Griffith. p.212-213

[109] Ibid. Frank. pp.495-497.

[110] The 1st Marine Division lost 621 KIA, 1,517 WIA and 5601 Malaria cases. Its Marines earned 5 Congressional Medals of Honor, 113 Navy Crosses and 4 Distinguished Service Medals. (McMillan pp.138-139)

[111] Ibid. Griffith. p.216

[112] Vandegrift would become Commandant of the Marine Corps in 1944.

[113] Johnston, Richard W. Follow Me! The Story of the Second Marine Division in World War II, Copyright 1948 by the 2nd Marine Division Historical Board and published by Random House, New York, NY. 1948. p.69

[114] Ibid. Frank. pp.528-534.

[115] Ibid. Johnston. p.72

[116] Ibid. Toland. pp. 421-426. Generals Sato and Tanaka engaged in a fist-fight ended by Tojo and the Emperor himself probed the High Command about the defeat and personal approved the Japanese withdraw.

[117] Ibid. Spector. p.213

[118] Ibid. Frank. p.557

[119] Ibid. p.560

[120] Ibid. p.566

[121] Ibid. p.567

[122] Bergerud, Eric. Touched With Fire: The Land War in the South Pacific, Penguin Books, New York, NY 1996. p.192

[123] Ibid. p.570

[124] Ibid. p.595 Depending on the source the Japanese withdrew anywhere from 10,000 to 13,000 troops from the island.

[125] Ibid. Griffith. p.244

[126] Ibid.

[127] Ibid. Morison. History of Naval Operations, p.371.

[128] Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. For the Common Defense: Fighting the Second World War, The Belknap Press or Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2000. p.215

[129] Ibid. Toland. p.431

Bibliography

Bergerud, Eric. Touched With Fire: The Land War in the South Pacific, Penguin Books, New York, NY 1996

Costello, John. The Pacific War 1941-1945, Quill Publishers, New York, NY. 1981

Frank, Richard B. Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle, Penguin Books, New York, NY 1990

Griffith, Samuel B II. The Battle for Guadalcanal originally published by Lippincott, New York, 1963, University of Illinois Press, Champaign IL, 2000

Johnston, Richard W. Follow Me! The Story of the Second Marine Division in World War II, Copyright 1948 by the 2nd Marine Division Historical Board and published by Random House, New York, NY. 1948

Liddle-Hart, B.H. History of the Second World War G.P. Putnam’s Son’s. New York, NY 1970

McMillan, George. The Old Breed: A History of the First Marine Division in WWII, The Infantry Journal Incorporated, Washington DC. 1949

Morison, Samuel Elliott, The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War, Little, Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto, 1963

Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. For the Common Defense: Fighting the Second World War, The Belknap Press or Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2000

Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan, The Free Press, New York, NY

Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945, Random House Publishers, New York, 1970

Tregaskis, Richard, Guadalcanal Diary, Originally published by Random House, 1943. Modern Library Paperback edition, Random House Publishers, NY 2000, with an introduction by Mark Bowden