Friends of Padre Steve’s World

This is the final installment `of a very long chapter in my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text. The chapter is different because instead of simply studying the battle my students also get some very detailed history about the ideological components of war that helped make the American Civil War not only a definitive event in our history; but a war of utmost brutality in which religion drove people and leaders on both sides to advocate not just defeating their opponent, but exterminating them.

But the study of this religious and ideological war is timeless, for it helps us to understand the ideology of current rivals and opponents, some of whom we are in engaged in battle and others who we spar with by other means, nations, tribes and peoples whose world view, and response to the United States and the West, is dictated by their religion.

Yet for those more interested in current American political and social issues the period is very instructive, for the religious, ideological and political arguments used by Evangelical Christians in the ante-bellum period, as well as many of the attitudes displayed by Christians in the North and the South are still on display in our current political and social debates.

I probably will write something using some of these ideas in a contemporary setting tomorrow….

Peace

Padre Steve+

The Attack on Lawrence Kansas

The Bloody Battle for Kansas

The struggle between the rival factions in Kansas increased in intensity as Free states and slave states alike poured in settlers and resources to control the territory. However, by the fall of 1855 it appeared that the free-state forces were gaining strength and now enjoyed a numerical superiority to the slave state supporters. That changed when President Franklin Pierce “gave official recognition to a territorial government dominated by proslavery forces- a government that decreed the laws of Missouri in force in Kansas as well.” [1]

That government decreed that:

“Public office and jury service were restricted to those with demonstrably proslavery options. Publicly to deny the right to hold slaves became punishable by five year’s imprisonment. To assist fugitive slaves risked a ten-year sentence. The penalty for inciting slave rebellion was death.” [2]

Rich Southerners recruited poor whites to fight their battles to promote the institution of slavery. Jefferson Buford of Alabama recruited hundreds of non-slaveholding whites to move to Kansas. Buford claimed to defend “the supremacy of the white race” he called Kansas “our great outpost” and warned that “a people who would not defend their outposts had already succumbed to the invader.” [3]

To this end he and 415 volunteers went to Kansas, where they gained renown and infamy as members of “Buford’s Cavalry.” The day they left Montgomery they were given a sendoff. Each received a Bible, and the “holy soldiers elected Buford as their general. Then they paraded onto the steamship Messenger, waving banners conveying Buford’s twin messages: “The Supremacy of the White Race” and “Kansas the Outpost.” [4] His effort ultimately failed but he had proved that “Southern poor men would kill Yankees to keep blacks ground under.” [5]

By the end of 1855 the free-state citizens had established their own rival government which provoked proslavery settlers who “bolstered by additional reinforcements from Missouri invaded the free-state settlement of Lawrence, destroyed its two newspapers, and demolished or looted nearby homes and businesses.” [6] Federal troops stationed in Lawrence “stood idly by because they had received no orders from the inert Pierce administration.” [7]

In response Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts began a two day speech on the Senate floor known as “The Crime Against Kansas” in which he condemned the assault on Lawrence which he described as “the anteroom to civil war.” [8] Sumner’s speech was a clarion call to partisans on both sides regarding the serious nature of what had taken place in Lawrence and it burst like a bombshell in the hallowed halls of the Senate. Sumner proclaimed “Murderous robbers from Missouri…hirelings picked from the drunken spew and vomit of an uneasy civilization” [9] had committed:

“The rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery; and it may clearly be traced to a depraved longing for a new slave State, the hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of Slavery in the National Government.” [10]

Sumner painted an even bleaker picture of the meaning what he believed was to come noting that the “rape” of Lawrence was the evidence that:

“The horrors of intestine feud” were being planned “not only in this distant Territory, but everywhere throughout the country. Already the muster has begun. The strife is no longer local, but national. Even now while I speak, portents hang on all the arches of the horizon, threatening to darken the land, which already yawns with, the mutterings of civil war.” [11]

Representative Preston Brooks attacks Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate Chamber

The effects of Sumner’s speech were equally dramatic, partially because he also personally insulted a number of influential Southern Senators while making it. Two days after the speech, while sitting at his desk in a nearly deserted Senate floor, Sumner was attacked by South Carolina representative Preston Brooks, who was related to one of the men, Senator Andrew P. Butler, who Sumner had insulted in his “Crime against Kansas” speech.

Northern extremists were also at work in Kansas carrying on their own holy war against supporters of slavery. One was John Brown who wrote:

“I rode into Kansas territory in eighteen and fifty-five in a one-horse wagon filled with revolvers, rifles, powder, and two-edged artillery broadswords. I expected war to break out between the free-state forces and the Border Ruffians, and I was ready to buckle on my armor and give battle…

In John Brown Jr.’s words I heard the thundering voice of Jehovah exhorting me to slaughter the Border Ruffians as He’s called Gideon to slay the Midianites. Yes, my greatest or principle object – eternal war against slavery – was to be carried out in Kansas Territory. Praise be God!…” [12]

John Brown’s Pottawatomie Massacre

Following the attack by the Border Ruffians on Lawrence Kansas, Brown and his company of volunteers went into action against a pro-slavery family at the settlement of Pottawatomie Creek. Brown and his sons attacked the family in their cabin, “dragged three men outside, shot the father through the head, and hacked his two sons with broadswords. Ritual murders.” [13] But Brown was not done; he went to two more cabins hacking his victims to death with the broadswords. Brown wrote:

“On the way back to camp, I was transfixed. The proslavery Philistines had murdered five or six free-state men in the great struggle for the soul of Kansas. Now we had got five of them. God alone is my judge. His will be done.” [14]

The issue in Kansas remained bloody and full of political intrigue. Free-state settlers and proslavery elements battled for the control of the territory. “Throughout the summer and early fall of 1856, armies marched and counter-marched, threatening one another with blood-curdling threats, terrorizing peaceably inclined settlers, committing depredations upon those who could not defend themselves, and killing with enough frequency to give validity to the term “Bleeding Kansas.” [15]

The political battle centered on the Lecompton Constitution which allowed slavery, but which had been rejected by a sizable majority of Kansas residents. The divide was so deep and contentious that that Kansas would not be admitted to the Union until after the secession of the Deep South. But the issue had galvanized the political parties of the North, and for the first time a coalition of “Republicans and anti-Lecompton Douglas Democrats, Congress had barely turned back a gigantic Slave Power Conspiracy to bend white men’s majoritarianism to slavemaster’s dictatorial needs, first in Kansas, then in Congress.” [16]

Attempts to Expand Slavery into the Territories and Beyond

The Last Slave Ship, the Schooner Wanderer

Taking advantage of the judicial ruling Davis and his supporters in Congress began to bring about legislation not just to ensure that Congress could not “exclude slavery” but to protect it in all places and all times. They sought a statute that would explicitly guarantee “that slave owners and their property would be unmolested in all Federal territories.” This was commonly known in the south as the doctrine of positive protection, designed to “prevent a free-soil majority in a territory from taking hostile action against a slave holding minority in their midst.” [17]

Other extremists in the Deep South had been long clamoring for the reopening of the African slave trade. In 1856 a delegate at the 1856 commercial convention insisted that “we are entitled to demand the opening of this trade from an industrial, political, and constitutional consideration….With cheap negroes we could set hostile legislation at defiance. The slave population after supplying the states would overflow to the territories, and nothing could control its natural expansion.” [18] and in 1858 the “Southern Commercial Convention…” declared that “all laws, State and Federal, prohibiting the African slave trade, out to be repealed.” [19] The extremists knowing that such legislation would not pass in Congress then pushed harder; instead of words they took action.

In 1858 there took place two incidents that brought this to the fore of political debate. The schooner Wanderer owned by Charles Lamar successfully delivered a cargo of four hundred slaves to Jekyll Island, earning him “a large profit.” [20] Then the USS Dolphin captured “the slaver Echo off Cuba and brought 314 Africans to the Charleston federal jail.” [21] The case was brought to a grand jury who had first indicted Lamar were so vilified that “they published a bizarre recantation of their action and advocated the repeal of the 1807 law prohibiting the slave trade. “Longer to yield to a sickly sentiment of pretended philanthropy and diseased mental aberration of “higher law” fanatics…” [22] Thus in both cases juries and judges refused to indict or convict those responsible.

Evangelical supporters of the efforts to re-open the slave trade argued that if the slave trade was re-opened under “Christian slaveholders instead of course Yankees scrupulously conducting the traffic, the trade would feature fair transactions in Africa, healthy conditions on ships, and Christian salvation in America.” [23]

There arose in the 1850s a second extremist movement in the Deep South, this one which had at its heart the mission to re-enslave free blacks. This effort was not limited to fanatics, but entered the Southern political mainstream, to the point that numerous state legislatures were nearly captured by majorities favoring such action. [24] That movement which had appeared out of nowhere soon fizzled, as did the bid to reopen the slave trade, but these “frustrations left extremists the more on the hunt for a final solution” [25] which would ultimately be found in secession.

Secession and war was now on the horizon, and despite well-meaning efforts of some politicians on both sides to find a way around it, it would come. Religion had been at the heart of most of the ideological debates of the preceding quarter century, and Evangelical Protestants on both sides had not failed to prevent the war; to the contrary those Evangelical leaders were instrumental in bringing it about as they:

“fueled the passions for a dramatic solution to transcendent moral questions. Evangelical religion did not prepare either side for the carnage, and its explanations seemed less relevant as the war continued. The Civil War destroyed the Old South civilization resting on slavery; it also discredited evangelical Protestantism as the ultimate arbiter of public policy.” [26]

The Battle Lines Solidify: A House Divided

Abraham Lincoln in 1856

Previously a man of moderation Lincoln laid out his views in the starkest terms in his House Divided speech given on June 16th 1858. Lincoln understood, possibly with more clarity than others of his time that the divide over slavery was too deep and that the country could not continue to exist while two separate systems contended with one another. Lincoln for his part was a gradualist and moderate approach to ending slavery in order to preserve the Union. However, Lincoln, like Davis, though professed moderates had allowed “their language to take on an uncompromising quality,” and because the mood of the country was such that neither man “could regard a retreat from his particular position as surrender- hence there could be no retreat at all.” [27]

The Union Lincoln “would fight to preserve was not a bundle of compromises that secured the vital interests of both slave states and free, …but rather, the nation- the single, united, free people- Jefferson and his fellow Revolutionaries supposedly had conceived and whose fundamental principles were now being compromised.” [28] He was to the point and said in clear terms what few had ever said before, in language which even some in his own Republican Party did not want to use because they felt it was too divisive:

“If we could first know where we are and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year since a policy was initiated with the avowed object and confident promise of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only not ceased but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; I do not expect the house to fall; but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the states, old as well as new, North as well as South.” [29]

Part of the divide was rooted in how each side understood the Constitution. For the South it was a compact among the various states, or rather “only a league of quasi independent states that could be terminated at will” [30] and in their interpretation States Rights was central. In fact “so long as Southerners continued to believe that northern anti-slavery attacks constituted a real and present danger to Southern life and property, then disunion could not be ruled out as an ugly last resort.” [31]

But such was not the view in the North, “for devout Unionists, the Constitution had been framed by the people rather than created as a compact among the states. It formed a government, as President Andrew Jackson insisted of the early 1830s, “in which all the people are represented, which operates directly on the people individually, not upon the States.” [32] Lincoln like many in the North understood the Union that “had a transcendent, mystical quality as the object of their patriotic devotion and civil religion.” [33]

Lincoln’s beliefs can be seen in the Gettysburg Address where he began his speech with the words “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal…” To Lincoln and others the word disunion “evoked a chilling scenario within which the Founders’ carefully constructed representative government failed, triggering “a nightmare, a tragic cataclysm” that would subject Americans to the kind of fear and misery that seemed to pervade the rest of the world.” [34]

Those same beliefs were found throughout the leaders of the Abolition movement, including Theodore Parker who said “The first [step] is to establish Slavery in all of the Northern States- the Dred Scott decision has already put it in all the territories….I have no doubt The Supreme Court will make the [subsequent] decisions.” [35]

Even in the South there was a desire for the Union and a fear over its dissolution, even among those officers like Robert E. Lee who would resign his commission and take up arms against the Union in defense of his native state. Lee wrote to his son Custis in January 1861, “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than the dissolution of the Union…I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation…Secession is nothing but revolution.” But he added “A Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets has no charms for me….” [36] The difference between Lee and others like him and Abraham Lincoln was how they viewed the Union, views which were fundamentally opposed.

Alexander Stephens who became the Confederate Vice President was not at all in favor of disunion. A strict constructionist who believed fervently in state’s rights he believed the South was best served to remain in the Union. As the divide grew he remarked “that the men who were working for secession were driven by envy, hate jealousy, spite- “these made war in heaven, which made devils of angels, and of the same passions will make devils of men. Patriotism in my opinion, had no more to do with it than love of God had to do with the other revolt.” [37]

John Brown

In the North there too existed an element of fanaticism. While “the restraining hand of churches, political parties and familial concerns bounded other antislavery warriors,” [38] and while most abolitionists tried to remain in the mainstream and work through legislation and moral persuasion to halt the expansion of slavery with the ultimate goal of emancipation; there were fanatical abolitionists that were willing to attempt to ignite the spark which would cause the powder keg of raw hatred and emotion to explode.

Most prominent among these men was John Brown. Brown was a “Connecticut-born abolitionist…a man with the selfless benevolence of the evangelicals wrought into a fiery determination to crush slavery” [39] who as early as 1834 was “an ardent sympathizer the Negroes” desiring to raise a black child in his own home and to “offering guidance to a colony of Negroes on the farm of the wealthy abolitionist Gerrit Smith at North Elba New York.” [40] Brown regarded moderate free-staters with distain and in Kansas set about to change the equation when he and a company of his marauders set upon and slaughtered the family of a pro-slavery settler at Pottawatomie Creek. [41]

The example of John Brown provides us a good example to understand religious extremism, especially when it becomes violent. The counterinsurgency field manual notes in words that are certainly as applicable to Brown as they are to current religiously motivated terrorists that “Religious extremist insurgents….frequently hold an all-encompassing worldview; they are ideologically rigid and uncompromising…. believing themselves to be ideologically pure, violent religious extremists brand those they consider insufficiently orthodox as enemies.”[42]

Brown was certainly “a religious zealot…but was nevertheless every much the product of his time and place….” [43] Brown was a veteran of the violent battles in Kansas where he had earned the reputation as “the apostle of the sword of Gideon” as he and his men battled pro-slavery settlers. Brown was possessed by the belief that God had appointed him as “God’s warrior against slaveholders.” [44] He despised the peaceful abolitionists and demanded action. “Brave, unshaken by doubt, willing to shed blood unflinchingly and to die for his cause if necessary, Brown was the perfect man to light the tinder of civil war in America, which was what he intended to do.” [45] Brown told William Lloyd Garrison and other abolitionist leaders after hearing Garrison’s pleas for peaceful abolition that:

“We’ve reached a point,” I said, “where nothing but war can get rid of slavery in this guilty nation. It’s better that a whole generation of men, women, and children should pass away by a violent death than that slavery should continue to exist.” I meant that literally, every word of it.” [46]

Following that meeting, as well as a meeting with Frederick Douglass who rejected Brown’s planned violent action, Brown went about collecting recruits for his cause and set out to seize 10,000 muskets at the Federal armory in Harper’s Ferry Virginia in order to ignite a slave revolt. Brown and twenty-one followers, sixteen whites and five blacks moved on the arsenal, as they went Brown:

“believed that we would probably fail at the Ferry, would probably die. But I believed that all we had to do was make the attempt, and Jehovah would do the rest: the Heavens would turn black, the thunder would rend the sky, and a mighty storm would uproot this guilty land, washing its sins away with blood. With God’s help, I, John Brown, would effect a mighty conquest even though it was like the last victory of Samson.” [47]

U.S. Marines under Command of Colonel Robert E. Lee storm Harper’s Ferry

After initial success in capturing the armory Brown’s plan was was frustrated and Brown captured, by a force of U.S. Marines led by Colonel Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart. Brown was tried and hung, but his raid “effectively severed the country into two opposing parts, making it clear to moderates there who were searching for compromise, that northerner’s tolerance for slavery was wearing thin.” [48]

It now did not matter that Brown was captured, tried, convicted and executed for his raid on Harper’s Ferry. He was to be sure was “a half-pathetic, half-mad failure, his raid a crazy, senseless exploit to which only his quiet eloquence during trial and execution lent dignity” [49] but his act was the watershed from which the two sides would not be able to recover, the population on both sides having gone too far down the road to disunion to turn back.

Brown had tremendous support among the New England elites, the “names of Howe, Parker, Emerson and Thoreau among his supporters.” [50] To abolitionists he had become a martyr “but to Frederick Douglass and the negroes of Chatham, Ontario, nearly every one of whom had learned something from personal experience on how to gain freedom, Brown was a man of words trying to be a man of deeds, and they would not follow him. They understood him, as Thoreau and Emerson and Parker never did.” [51]

But to Southerners Brown was the symbol of an existential threat to their way of life. In the North there was a nearly religious wave of sympathy for Brown, and the “spectacle of devout Yankee women actually praying for John Brown, not as a sinner but as saint, of respectable thinkers like Thoreau and Emerson and Longfellow glorifying his martyrdom in Biblical language” [52] horrified Southerners, and drove pro-Union Southern moderates into the secession camp.

The Hanging of John Brown

The day that Brown went to his hanging he wrote his final missive. This was written once more in apocalyptic language, but also in which he portrayed himself as a Christ figure going to his cross on the behalf of a guilty people, but a people who his blood would not atone:

“It’s now December second – the day of my hanging, the day the gallows become my cross. I’m approaching those gallows while sitting on my coffin in the bed of a military wagon. O dear God, my eyes see the glory in every step of the divine journey that brought me here, to stand on that platform, in that field, before all those soldiers of Virginia. Thank you, Father, for allowing an old man like me such might and soul satisfying rewards. I am ready to join thee now in Paradise…

They can put the halter around my neck, pull the hood over my head. Hanging me won’t save them from God’s wrath! I warned the entire country: I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with blood.” [53]

Brown’s composure and dignity during the trial impressed Governor Henry Wise of Virginia who signed Brown’s death warrant and fire eater Edmund Ruffin, and in his diary Ruffin “praised Brown’s “animal courage” and “complete fearlessness & insensibility to danger and death.” [54]

Brown’s death was marked with signs of mourning throughout the North, for Brown was now a martyr. Henry David Thoreau “pronounced Brown “a crucified hero,” [55] while through the North Brown’s death was treated as a martyr’s death. Even abolitionists like Garrison who had condemned violence in the quest of emancipation praised Brown’s actions while throughout the North:

“Church bells tolled, black bunting was hung out, minute guns were fired, prayer meetings assembled, and memorial resolutions adopted. In the weeks following, the emotional outpouring continued: lithographs of Brown circulated in vast numbers, subscriptions were organized for the support of his family, immense memorial meetings took place in New York, Boston and Philadelphia…” [56]

But in the South there was a different understanding. Despite official denunciations of Brown by Lincoln and other Republican leaders, the message was that the North could not be trusted. Brown’s raid, and the reaction of Northerners to it “was seized upon as argument-clinching proof that the North was only awaiting its opportunity to destroy the South by force….” [57]

The Election of Abraham Lincoln

The crisis continued to fester and when Lincoln was elected to the Presidency in November 1860 with no southern states voting Republican the long festering volcano erupted. It did not take long before southern states began to secede from the Union. Alexander Stephens told a friend who asked him “why must we have civil war?”

“Because there are not virtue and patriotism and sense enough left in the country to avoid it. Mark me, when I repeat that in less than twelve months we shall be in the midst of a bloody war. What will become of us then God only knows.” [58]

But Stephens’ warning fell on deaf ears as passionate secessionist commissioners went throughout the South spreading their message. South Carolina was the first to secede, followed by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. Many of the declarations of causes for secession made it clear that slavery was the root cause. The declaration of South Carolina is typical of these and is instructive of the basic root cause of the war:

“all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. He is to be entrusted with the administration of the common Government, because he has declared that that “Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free,” and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction.”[59]

Throughout the war slavery loomed large, even though in the beginning of abolition controversies of the 1830s many northerners “were content to tolerate slavery’s indefinite survival in the South so long as it did not impinge on their own rights and aspirations at home.” [60] Such attitudes were still common in the North during the late 1850s, especially among Democrats.

But it was the multiple transgressions of slavery supporters to advance those rights in the courts, through the extension of slavery to the territories, to allow slaveholders to recover their human “property” in northern states during the 1850s taught northerners “just how fundamental and intractable the differences with Southern political leaders were. Thus educated, most northern voters had decided by 1860 that only an explicitly anti-slavery party could protect their interests.” [61]

The results of the divide in American politics were such that in the election of 1860 Abraham Lincoln carried all eighteen Free states with a total of “180 electoral votes- 27 more than he needed for victory.” Lincoln had clear majorities in all but three of the states he won and carried 55 percent of the overall vote in the North. [62] Lincoln won no Southern State during the campaign. The election symbolized the extreme polarization of the respective electorates in both the North and the South. The Baptist clergyman James Furman expressed the outrage and paranoia of many in the South by warning after Lincoln’s election “If you are tame enough to submit, Abolition preachers will be at hand to consummate the marriage of your daughters to black husbands.” [63]

William Lloyd Garrison, again using biblical imagery as well as astute analysis of the behavior of Southern leaders after the election of 1860, wrote that the Southern response to Lincoln’s election:

“Never had the truth of the ancient proverb “Whom the gods intend to destroy, they first make mad” been more signally illustrated than in the condition of southern slaveholders following Lincoln’s election. They were insane from their fears, their guilty forebodings, their lust for power and rule, hatred of free institutions, their merited consciousness of merited judgments; so that they may be properly classed as the inmates of a lunatic asylum. Their dread of Mr. Lincoln, of his Administration, of the Republican Party, demonstrated their insanity. In vain did Mr. Lincoln tell them, “I do not stand pledged to the abolition of slavery where it already exists.” They raved just as fiercely as though he were another John Brown, armed for southern invasion and universal emancipation! In vain did the Republican party present one point of antagonism to slavery – to wit, no more territorial expansion. In vain did that party exhibit the utmost caution not to give offense to any other direction – and make itself hoarse in uttering professions of loyalty to the Constitution and the Union. The South protested that it’s designs were infernal, and for them was “sleep no more!” Were these not the signs of a demented people?” [64]

But both sides were blind to their actions and with few exceptions most leaders, especially in the South, badly miscalculated the effects of the election of 1860. The leaders in the North did not realize that the election of Lincoln would mean the secession of one or more Southern states, and Southerners “were not able to see that secession would finally mean war” [65] despite the warnings of Alexander Stephens to the contrary.

The five slave states of the lower South: “appointed commissioners to the other slave states, and instructed them to spread the secessionist message across the entire region. These commissioners often explained in detail why their states were exiting the Union, and they did everything in their power to persuade laggard slave states to join the secessionist cause. From December 1860 to April 1861 they carried the gospel of disunion to the far corners of the South.” [66]

Secession Convention in Charleston South Carolina

Slavery and the superiorly of the white race over blacks was at the heart of the message brought by these commissioners to the yet undecided states. Former Congressman John McQueen of South Carolina wrote to secessionists in Virginia “We, of South Carolina, hope to greet you in a Southern Confederacy, where white men shall rule our destinies, and from which we may transmit our posterity the rights, privileges and honor left us by our ancestors.” [67] In Texas McQueen told the Texas Convention: “Lincoln was elected by a sectional vote, whose platform was that of the Black Republican part and whose policy was to be the abolition of slavery upon this continent and the elevation of our own slaves to an equality with ourselves and our children.” [68]

In his First Inaugural Address Lincoln noted: “One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.”[69] Of course he was right, and his southern opponents agreed.

As the war began, white Southerners of all types and classes rallied to the call of war against the hated Yankee. The common people, the poor yeomen farmers were often the most stalwart defenders of the South. With the Orwellian slogan “Freedom is not possible without slavery” ringing in their ears, they went to war against the Yankees alongside their slave-owning neighbors to “perpetuate and diffuse the very liberty for which Washington bled, and which the heroes of the Revolution achieved.” [70]

Alexander Stephens

Alexander Stephens the new Vice President of the Confederacy, who had been a devout Unionist and even had a friendly relationship with Lincoln in the months and years leading up to the war explained the foundation of the Southern state in his Cornerstone Speech of March 21st 1861:

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner- stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition. [Applause.] This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”[71]

Thus the American ideological war was born; it had taken decades to reach the point of no return. It had taken years of frustration, attempts at compromise by politicians who attempted to dodge the moral issues inherent in slavery. Time could not heal the wounds caused by slavery as long as “one section of the country regarded it as a blessing, the other as a curse.” [72] Frederick Douglass observed: “Whatever was done or attempted with a view to the support and secularity of slavery on served to fuel the fire, and heated the furnace of [anti-slavery] agitation to a higher degree than had any before attained.” [73]

“The Heather is on Fire…”

As no middle ground remained, the nation plunged into war with many leaders, especially church leaders forged ahead to claim the mantle of Christ and God for their side; and given the widely held theological “assumptions about divine sovereignty and God’s role in human history, northerners and southerners anxiously looked for signs of the Lord’s favor.” [74] Of course people on both sides used the events of any given day during the war to interpret what this meant and both were subject to massive shifts as the God of Battles seemed to at times favor the armies of the Confederacy and as the war ground on to favor those of the Union.

Those who had been hesitant about secession in the South were overcome by events when Fort Sumter was attacked. Edmund Ruffin spoke for many of the ardent secessionists when he proclaimed “The shedding of blood…will serve to change many voters in the hesitating states, from submission or procrastinating ranks, to the zealous for immediate secession.” [75] But very few of the radical secessionists found their way into uniform or into the front lines. Then like now, very few of those who clamor for war and vengeance the most, and who send the sons of others to die in their wars, take up arms themselves.

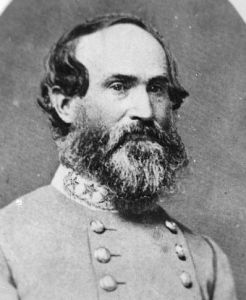

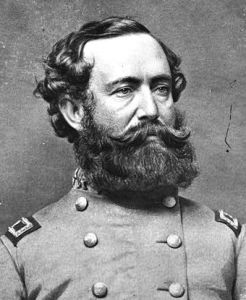

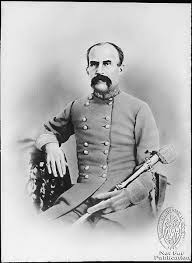

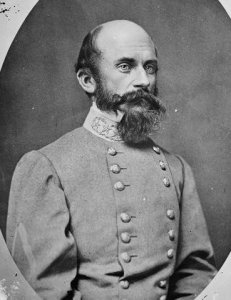

Confederate General Jubal Early saw the sour irony in this. Early had fought against secession until the last as a legislator during the Virginia secession debate, and when he finally accepted secession and went to war he never looked back. During the war became one of the most committed Rebels of the Cause. That being said he was not fond of the proponents of secession and took pleasure as the war went on in taunting “the identifiable secessionists in gray uniform who came his way, especially when the circumstances were less than amusing….” [76]After the disastrous defeat at the Third Battle of Winchester in 1864, Early looked at his second in command, former Vice President of the United States and Confederate Major General John C. Breckinridge, who had advocated secession as they retreated amid the “chaos and horror of his army’s rout. Early took the occasion to mock his celebrated subordinate: “Well General, he crowed, “what do you think of the ‘rights of the South’ in the territories now?” [77]

In the North a different sentiment rose as one volunteer soldier from Pennsylvania wrote: “I cannot believe…that “Providence intends to destroy this Nation, the great asylum for all the oppressed of all other nations and build a slave Oligarchy on the ruins thereof.” Another volunteer from Ohio mused “Admit the right of the seceding states to break up the Union at pleasure…and how long before the new confederacies created by the first disruption shall be resolved into smaller fragments and the continent become a vast theater of civil war, military license, anarchy and despotism? Better to settle it at whatever cost and settle it forever.” [78]

The depth of the religious dimension of the struggle can be seen in the hymn most commonly associated with the Civil War and the United States. This was the immensely popular Battle Hymn of the Republic whose lyricist Julia Ward Howe penned the lines “As he died to make men holy, let us live to make men free! While God is marching on” [79]

There was also an attempt on the part of Northern Evangelicals to push religion to the forefront of the conflict and to correct what they believed was an error in the Constitution, that error being that God was not mentioned in it. They believed that the Civil War was God’s judgment on the nation for this omission. The group, called the National Reform Association proposed the Bible Amendment. They met with Lincoln and proposed to modify the opening paragraph of the Constitution to read:

“We the people of the United States, humbly acknowledging Almighty God as the source of all authority and power and civil government, the Lord Jesus Christ as the Ruler among the nations, His revealed will as the supreme law of the land, in order to form a more perfect union.” [80]

While Lincoln brushed off their suggestion and never referred to the United States as a Christian nation, much to the chagrin of many Northern Christians, the Confederacy had reveled in its self-described Christian character. The Confederacy had “proudly invoked the name of God in their Constitution. Even late in the war, a South Carolina editor pointed to what he saw as a revealing fact: the Federal Constitution – with no reference to the Almighty – “could have been passed and adopted by Atheists or Hindoes or Mahometans.” [81]

When the Stars and Stripes came down on April 14th 1861 the North was galvanized as never before, one observer wrote: “The heather is on fire….I never knew what popular excitement can be… The whole population, men, women, and children, seem to be in the streets with Union favors and flags.” [82] The assault on Fort Sumter help to unify the North in ways not thought possible by Southern politicians who did not believe that Northerners had the mettle to go to war against them. But they were wrong, even Senator Stephen Douglas, Lincoln’s stalwart opponent of so many campaigns went to the White House for a call to national unity. Returning to Chicago he told a huge crowd just a month before his untimely death:

“There are only two sides to the question. Every man must be for the United States or against it. There can be no neutrals in this war, only patriots- or traitors” [83]

Colonel Robert E. Lee, a Virginian who looked askance at secession turned down the command of the Union Army when it was offered and submitted his resignation upon the secession of Virginia noting:

“With all my devotion to the Union and feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home. I have therefore, resigned my commission in the Army, and save in the defense of my native State…I hope I may never be called upon to draw my sword.” [84]

But throughout the South, most people rejoiced at the surrender of Fort Sumter. In Richmond the night following the surrender “bonfires and fireworks of every description were illuminating in every direction- the whole city was a scene of joy owing to [the] surrender of Fort Sumter” – and Virginia wasn’t even part of the Confederacy.” [85]

The Effect of the Emancipation Proclamation

Some twenty months after Fort Sumter fell and after nearly two years of unrelenting slaughter, culminating in the bloody battle of Antietam, Lincoln published the emancipation proclamation. It was a military order in which he proclaimed the emancipation of slaves located in the Rebel states, and it would be another two years, with the Confederacy crumbling under the combined Federal military onslaught before Lincoln was able to secure passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. The amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude throughout the country, as well as nullified the fugitive slave clause and the Three-Fifths Compromise.

Though limited in scope the Emancipation Proclamation had more than a social and domestic political effect, it ensured that Britain would not intervene in the war.

The Emancipation Proclamation and the elimination of slavery also impacted the Union war effort in terms of law, law which eventually had an impact around the world as nations began to adapt to the changing character of war. In the “Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field, General Orders No. 100 by President Lincoln, April 24, 1863; Prepared by Francis Lieber, LLD noted in Article 42 of that Code:

“Slavery, complicating and confounding the ideas of property, (that is of a thing,) and of personality, (that is of humanity,) exists according to municipal or local law only. The law of nature and nations has never acknowledged it. The digest of the Roman law enacts the early dictum of the pagan jurist, that “so far as the law of nature is concerned, all men are equal.” Fugitives escaping from a country in which they were slaves, villains, or serfs, into another country, have, for centuries past, been held free and acknowledged free by judicial decisions of European countries, even though the municipal law of the country in which the slave had taken refuge acknowledged slavery within its own dominions.” [86]

It continued in Article 43:

“Therefore, in a war between the United States and a belligerent which admits of slavery, if a person held in bondage by that belligerent be captured by or come as a fugitive under the protection of the military forces of the United States, such person is immediately entitled to the rights and privileges of a freeman To return such person into slavery would amount to enslaving a free person, and neither the United States nor any officer under their authority can enslave any human being. Moreover, a person so made free by the law of war is under the shield of the law of nations, and the former owner or State can have, by the law of postliminy, no belligerent lien or claim of service.” [87]

The threat of the destruction of the Union and the continuance of slavery in either the states of the Confederacy or in the new western states and territories, or the maintenance of the Union without emancipation was too great for some, notably the American Freedmen’s Commission to contemplate. They wrote Edwin Stanton in the spring of 1864 with Grant’s army bogged down outside of Richmond and the Copperheads and the Peace Party gaining in influence and threatening a peace that allowed Southern independence and the continuance of slavery:

“In such a state of feeling, under such a state of things, can we doubt the inevitable results? Shall we escape border raids after fleeing fugitives? No man will expect it. Are we to suffer these? We are disgraced! Are we to repel them? It is a renewal of hostilities!…In the case of a foreign war…can we suppose that they will refrain from seeking their own advantage by an alliance with the enemy?” [88]

In his Second Inaugural Address, Abraham Lincoln discussed the issue of slavery as the chief cause of the war. In it, Lincoln noted that slavery was the chief cause of the war in no uncertain terms and talked in a language of faith that was difficult for many, especially Christians, who “believed weighty political issues could be parsed into good or evil. Lincoln’s words offered a complexity that many found difficult to accept,” for the war had devastated the playground of evangelical politics, and it had “thrashed the certitude of evangelical Protestantism” [89] as much as the First World War shattered Classic European Christian Liberalism. Lincoln’s confrontation of the role that people of faith in bringing on the war in both the North and the South is both illuminating and a devastating critique of the religious attitudes that so stoked the fires of hatred. His realism in confronting facts was masterful, and badly needed, he spoke of “American slavery” as a single offense ascribed to the whole nation.” [90]

“One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”[91]

When Edmund Ruffin pulled the lanyard of the cannon that fired the first shot at Fort Sumter it marked the end of an era. Despite the efforts of Edmund Ruffin, Alexander Stephens, Jefferson Davis and so many others who advocated secession and war, the war that they launched in the hope of maintaining slavery; gave birth to what Lincoln described as “a new birth of freedom.”

When the war ended with the Confederacy defeated and the south in now in ruins, Ruffin still could not abide the result. In a carefully crafted suicide note he sent to his son the bitter and hate filled old man wrote on June 14th 1865:

“I here declare my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule- to all political, social and business connections with the Yankees and to the Yankee race. Would that I could impress these sentiments, in their full force, on every living Southerner and bequeath them to every one yet to be born! May such sentiments be held universally in the outraged and down trodden South, though in silence and stillness, until the now far-distant day shall arrive for just retribution for Yankee usurpation, oppression and outrages, and for deliverance and vengeance for the now ruined, subjugated and enslaved Southern States! … And now with my latest writing and utterance, and with what will be near my last breath, I here repeat and would willingly proclaim my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule — to all political, social and business connections with Yankees, and the perfidious, malignant and vile Yankee race.” [92]

A Southern Change of Tune: The War Not About Slavery after All, and the “New Religion” of the Lost Cause

Though Ruffin was dead in the coming years the southern states would again find themselves under the governance of former secessionists who were unabashed white supremacists. Former secessionist firebrands who had boldly proclaimed slavery to be the deciding issue when the war changed their story. Instead of slavery being the primary cause of Southern secession and the war, it was “trivialized as the cause of the war in favor of such things as tariff disputes, control of investment banking and the means of wealth, cultural differences, and the conflict between industrial and agricultural societies.” [93]

Alexander Stephens who had authored the infamous1861 Cornerstone Speech that “that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition” argued after the war that the war was not about slavery at all, that the war:

“had its origins in opposing principles….It was a strife between the principles of Federation, on the one side, and Centralism, or Consolidation on the other.” He concluded “that the American Civil War “represented a struggle between “the friends of Constitutional liberty” and “the Demon of Centralism, Absolutism, [and] Despotism!” [94]

Jefferson Davis, who had masterfully crafted “moderate” language which radicals in the South used to their advantage regarding the expansion and protection of the rights of slave owners in the late 1850s to mollify Northern Democrats, and who wrote in October 1860 that: “The recent declarations of the Black Republican part…must suffice to convince many who have formerly doubted the purpose to attack the institution of slavery in the states. The undying opposition to slavery in the United States means war upon it where it is, not where it is not.” [95]

After the war a revisionist Davis wrote:

“The Southern States and Southern people have been sedulously represented as “propagandists” of slavery, and the Northern as the champions of universal freedom…” and “the attentive reader…will already found enough evidence to discern the falsehood of these representations, and to perceive that, to whatever extent the question of slavery may have served as an occasion, it was far from being the cause for the conflict.” [96]

Instead of being about slavery the Confederate cause was mythologized by those promoting the false history of the “Lost Cause” a term coined by William Pollard in 1866, which “touching almost every aspect of the struggle, originated in Southern rationalizations of the war.” [97] By 1877 many southerners were taking as much pride in the “Lost Cause” as Northerners took in Appomattox.[98] Alan Nolen notes: “Leaders of such a catastrophe must account for themselves. Justification is necessary. Those who followed their leaders into the catastrophe required similar rationalization.” [99]

The Lost Cause was elevated by some to the level of a religion. In September 1906, Lawrence Griffith speaking to a meeting of the United Confederate Veterans stated that when the Confederates returned home to their devastated lands, “there was born in the South a new religion.” [100] The mentality of the Lost Cause took on “the proportions of a heroic legend, a Southern Götterdämmerung with Robert E. Lee as a latter day Siegfried.” [101]

This new religion that Griffith referenced was replete with signs, symbols and ritual:

“this worship of the Immortal Confederacy, had its foundation in myth of the Lost Cause. Conceived in the ashes of a defeated and broken Dixie, this powerful, pervasive idea claimed the devotion of countless Confederates and their counterparts. When it reached fruition in the 1880s its votaries not only pledged their allegiance to the Lost Cause, but they also elevated it above the realm of common patriotic impulse, making it perform a clearly religious function….The Stars and Bars, “Dixie,” and the army’s gray jacket became religious emblems, symbolic of a holy cause and of the sacrifices made on its behalf. Confederate heroes also functioned as sacred symbols: Lee and Davis emerged as Christ figures, the common soldier attained sainthood, and Southern women became Marys who guarded the tomb of the Confederacy and heralded its resurrection.” [102]

Jefferson Davis became an incarnational figure for the adherents of this new religion. A Christ figure who Confederates believed “was the sacrifice selected-by the North or by Providence- as the price for Southern atonement. Pastors theologized about his “passion” and described Davis as a “vicarious victim”…who stood mute as Northerners “laid on him the falsely alleged iniquities of us all.” [103]

In 1923 a song about Davis repeated this theme:

Jefferson Davis! Still we honor thee! Our Lamb victorious,

who for us endur’d A cross of martyrdom, a crown of thorns,

soul’s Gethsemane, a nation’s hate, A dungeon’s gloom!

Another God in chains.” [104]

The myth also painted another picture, that of slavery being a benevolent institution which has carried forth into our own time. The contention of Southern politicians, teachers, preachers and journalists was that slaves liked their status; they echoed the words of slave owner Hiram Tibbetts to his brother in 1842 “If only the abolitionists could see how happy our people are…..The idea of unhappiness would never enter the mind of any one witnessing their enjoyments” [105] as well as Jefferson Davis who in response to the Emancipation Proclamation called the slaves “peaceful and contented laborers.” [106]

The images of the Lost Cause, was conveyed by numerous writers and Hollywood producers including Thomas Dixon Jr. whose play and novel The Clansman became D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, a groundbreaking part of American cinematography which was released in 1915; Margaret Mitchell who penned the epic Pulitzer Prize winning novel Gone With the Wind which in its 1939 film form won ten academy awards immortalized the good old days of the old South with images of faithful slaves, a theme which found its way into Walt Disney’s famed 1946 animated Song of the South.

D.W. Griffith Birth of a Nation

The Lost Cause helped buttress the myths that both comforted and inspired many Southerners following the war. “It defended the old order, including slavery (on the grounds of white supremacy), and in Pollard’s case even predicted that the superior virtues of cause it to rise ineluctably from the ashes of its unworthy defeat.” [107] The myth helped pave the way to nearly a hundred more years of effective second class citizenship for now free blacks who were often deprived of the vote and forced into “separate but equal” public and private facilities, schools and recreational activities. The Ku Klux Klan and other violent organizations harassed, intimidated, persecuted and used violence against blacks.

“From the 1880s onward, the post-Reconstruction white governments grew unwilling to rely just on intimidation at the ballot box and themselves in power, and turned instead to systematic legal disenfranchisement.” [108] Lynching was common and even churches were not safe. It would not be until the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s that blacks would finally begin to gain the same rights enjoyed by whites in most of the South.

Despite this many Union veterans to their dying day fought the Lost Causers. Members of the Grand Army of the Republic, the first truly national veteran’s organization, and the first to admit African American soldiers as equals, and the predecessor of modern veteran’s groups, continued their fight to keep the public fixed on the reason for war, and the profound difference between what they believed that they fought for and what their Confederate opponents fought for during the war.

“The Society of the Army of the Tennessee described the war as a struggle “that involved the life of the Nation, the preservation of the Union, the triumph of liberty and the death of slavery.” They had fought every battle…from the firing on the Union flag Fort Sumter to the surrender of Lee at Appomattox…in the cause of human liberty,” burying “treason and slavery in the Potter’s Field of nations” and “making all our citizens equal before the law, from the gulf to the lakes, and from ocean to ocean.” [109]

At what amounted to the last great Blue and Gray reunion at Gettysburg was held in 1937, the surviving members of the United Confederate Veterans extended an invitation to the GAR to join them there. The members of the GAR’s 71st Encampment from Madison Wisconsin, which included survivors of the immortal Iron Brigade who sacrificed so much of themselves at McPherson’s Ridge on July 1st 1863 adamantly, opposed a display of the Confederate Battle flag. “No Rebel colors,” they shouted. “What sort of compromise is that for Union soldiers but hell and damnation.” [110]

Ruffin outlived Lincoln who was killed by the assassin John Wilkes Booth on April 14th 1864. However the difference between the two men was marked. In his Second Inaugural Address Lincoln spoke in a different manner than Ruffin. He concluded that address with these thoughts:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” [111]

Why this Matters Today

The American Civil War provides a complex drama that political leaders, diplomats and military leaders would be wise to study, and not simply the military aspects and battles. Though the issues may be different in nations where the United States decides to intervene to prevent humanitarian disasters, prevent local civil wars from becoming regional conflagrations, or to provide stability after a civil war, the conflict provides poignant example after poignant example. If we fail to remember them we will lose who we are as a nation.

The Union was preserved, reconciliation was to some degree. Albeit the reconciliation was very imperfectly achieved, as the continuance of racism and discrimination, and the lack of repentance on the part of many of those who shamelessly promoted the Lost Cause and their current defenders continues to this day. Allen Guelzo wrote in the American Interest about the importance of both reconciliation and repentance to Frederick Douglass after the war:

“Douglass wanted the South not only to admit that it had lost, but also that it had deserved to lose. “The South has a past not to be contemplated with pleasure, but with a shudder”, he wrote in 1870. More than a decade later, Douglass was still not satisfied: “Whatever else I may forget, I shall never forget the difference between those who fought to save the Republic and those who fought to destroy it.” [112]

Likewise, that imperfect but reunited Union was all that stood in the way of Nazi Germany in the dark days of early 1942. Had the American republic fragmented during the war; had the South won, as so many kings and dictators of the day either openly or secretly desired, there would have been nothing to stand in the way of Hitler, and there would be nothing to stand in the way of the modern despots, terrorists and dictatorships such as the Islamic State today.

The controversies and conflicts brought on by the ideological, social and religious divides in the Ante-Bellum United States provide current leaders with historical examples. Our Civil War was heavily influenced by religion and the ideologies of the partisans in the North and in the South who were driven by religious motives, be those of the evangelical abolitionists or the proslavery evangelicals. If one is honest, one can see much of the same language, ideology and religious motivation at play in our twenty-first century United States. The issue for the vast majority of Americans, excluding certain neo-Confederate and White Supremacist groups, is no longer slavery; however the religious arguments on both sides of the slavery debate find resonance in our current political debates.

Likewise, for military, foreign policy officials and policy makers the subject of the role of religion can be quite informative. Similar issues are just as present in many the current conflicts in the Middle East, Africa and Eastern Europe which are driven by the religious motives of various sects. The biggest of these conflicts, the divide between Sunni and Shia Moslems, is a conflict that threatens to engulf the region and spread further. In it religion is coupled with the quest for geopolitical and economic power. This conflict in all of its complexity and brutality is a reminder that religion is quite often the ideological foundation of conflict.

These examples, drawn from our own American experience can be instructive to all involved in policy making. These examples show the necessity for policy makers to understand just how intertwined the political, ideological, economic, social and religious seeds of conflict are, and how they cannot be disconnected from each other without severe repercussions.

Samuel Huntington wrote:

“People do not live by reason alone. They cannot calculate and act rationally in pursuit of their self-interest until they define their self. Interest politics presupposes identity. In times of rapid social change established identities dissolve, the self must be redefined, and new identities created. For people facing the need to determine Who am I? Where do I belong? Religion provides compelling answers….In this process people rediscover or create new historical identities. Whatever universalist goals they may have, religions give people identity by positing a basic distinction between believers and non-believers, between a superior in-group and a different and inferior out-group.” [113]

By taking the time to look at our own history as well as our popular mythology; planners, commanders and policy makers can learn lessons that if they take the time to learn will help them understand similar factors in places American troops and their allies might be called to serve, or that we might rather avoid.

Notes

[1] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.196

[2] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.196

[3] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.125

[4] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.126

[5] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.126

[6] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.196

[7] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.148

[8] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.81

[9] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.149

[10] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.81

[11] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.81

[12] Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.173

[13] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.118

[14] Ibid, Oates The Approaching Fury p.181

[15] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis pp.213-214

[16] Ibid. Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.142

[17] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.142

[18] McPherson, James. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1988 p.102

[19] Ibid Freehling, The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 p.183

[20] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.103

[21] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II p.183

[22] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.103

[23] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II pp.174-175

[24] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II p.185

[25] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II p.185

[26] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.360

[27] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.144

[28] Gallagher, Gary The Union War Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London, 2011 p.47

[29] Lincoln, Abraham A House Divided given at the Illinois Republican Convention, June 16th 1858, retrieved from www.pbs.org/wgbh/ala/part4/4h2934.html 24 March 2014

[30] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.55

[31] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.55

[32] Ibid. Gallagher The Union War p.46

[33] Ibid Gallagher The Union War p.47

[34] Ibid Gallagher The Union War p.47

[35] Wills, Garry. Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York 1992 p.114

[36] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.221

[37] Catton, Bruce The Coming Fury Phoenix Press, London 1961 p.46

[38] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II p.207

[39] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.81

[40] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.211

[41] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis pp.211-212

[42] Ibid. U.S. Army/ Marine Counterinsurgency Field Manual p.27

[43] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.197

[44] Ibid. Freehling The Road to Disunion Volume II p.207

[45] Ibid. Korda, Clouds of Glory p.xviii

[46] Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.203

[47] Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.284

[48] Ibid. Korda Clouds of Glory p.xxxix

[49] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.187

[50] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.381

[51] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.375

[52] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.187

[53] Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.290

[54] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.3

[55] Ibid. McPherson The Battlecry of Freedom p.210

[56] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.378

[57] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.119

[58] Ibid. Catton The Coming Fury pp.46-47

[59] __________ Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union. Retrieved from The Avalon Project, Yale School of Law http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_scarsec.asp 24 March 2014

[60] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.251

[61] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.253

[62] Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.442

[63] Ibid. McPherson Drawn With Sword p.50 These words are little different than the words of many conservative Evangelical Christian pastors, pundits and politicians today in relation to the legalization of Gay marriage.

[64] Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.342

[65] Ibid. Catton The Coming Fury p.122

[66] Ibid. Dew Apostles of Disunion p.18

[67] Ibid. Dew Apostles of Disunion p.48

[68] Ibid. Dew Apostles of Disunion p.48

[69] Lincoln, Abraham First Inaugural Address March 4th 1861 retrieved from www.bartleby.com/124/pres31.html 24 March 2014

[70] Ibid. McPherson Drawn With Sword pp.50-51

[71] Cleveland, Henry Alexander H. Stevens, in Public and Private: With Letters and Speeches, before, during and since the War, Philadelphia 1886 pp.717-729 retrieved from http://civilwarcauses.org/corner.htm 24 March 2014

[72] Ibid. Catton Two Roads to Sumter p.143

[73] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.253

[74] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.74

[75] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.273

[76] Osborne, Charles C. Jubal: The Life and Times of General Jubal A. Earl, CSA Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill NC 1992 p.52

[77] Ibid. Osborne Jubal p.52

[78] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free pp.253-254

[79] Ibid. Huntington Who Are We? P.77

[80] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.360

[81] Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples pp.337-338

[82] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.274

[83] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.274

[84] Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.85

[85] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.140

[86] Reichberg, Gregory M, Syse Henrik, and Begby, Endre The Ethics of War: Classic and Contemporary Readings Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Malden, MA and Oxford UK 2006 p.570

[87] Ibid. Reichberg et al. The Ethics of War p.570

[88] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.534

[89] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.358

[90] Ibid. Wills Lincoln at Gettysburg p.186

[91] Lincoln, Abraham Second Inaugural Address March 4th 1865 retrieved from www.bartleby.com/124/pres32.html 24 March 2014

[92] Edmund Ruffin (1794-1865). Diary entry, June 18, 1865. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Retrieved from http://blogs.loc.gov/civil-war-voices/about/edmund-ruffin/ 24 March 2014

[93] Gallagher, Gary W. and Nolan Alan T. editors The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 2000 p.15

[94] Ibid. Dew Apostles of Disunion p.16

[95] Ibid. Catton The Coming Fury p.104

[96] Davis, Jefferson The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government Volume One of Two, A public Domain Book, Amazon Kindle edition pp.76-77

[97] Ibid. Gallagher and Nolan The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History p.12

[98] Millet Allen R and Maslowski, Peter. For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America The Free Press, a division of McMillan Publishers, New York 1984 p.230

[99] Ibid. Gallagher and Nolan The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History p.12

[100] Hunter, Lloyd The Immortal Confederacy: Another Look at the Lost Cause Religion in Gallagher and Nolan The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War p.185

[101] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.854

[102] Ibid. Hunter The Immortal Confederacy Religion in Gallagher and Nolan The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War p.186

[103] Ibid. Hunter The Immortal Confederacy Religion in Gallagher and Nolan The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War p.198

[104] Ibid. Hunter The Immortal Confederacy Religion in Gallagher and Nolan The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War p.198

[105] Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.106

[106] Ibid. Gallagher and Nolan The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History p.16

[107] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.525

[108] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.526

[109] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.532

[110] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.532

[111] Ibid. Lincoln Second Inaugural Address

[112] Guelzo, Allen C. A War Lost and Found in The American Interest September 1st 2011 retrieved 30 October 2014 from http://www.the-american-interest.com/articles/2011/09/01/a-war-lost-and-found/

[113] Ibid. Huntington The Clash of Civilizations p.97